Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (132 page)

The first section of the Sanctus ends with the soloists murmuring

Dominus Deus Sabaoth

at

pianissimo

, like priests at a distant altar. The

Pleni sunt coeli

, Heaven and earth are full of Thy glory, breaks out in a soaring fugue surrounded by racing strings. While the whole of the

Missa solemnis

is informed by Handel, this may be the most overtly Handelian moment.

44

The

Pleni

fugue is answered by a short, skipping fugue in 3/4 that dispenses briskly with

Hosanna in excelsis

. Many composers dwell on that line, but Beethoven wants to get on to his central section. From the

Hosanna

he shifts direction in seconds.

45

The next pages, for orchestra alone, in a remarkable subdued organlike color, echo the beginning of the movement, with divided violas and cellos, the texture made ethereal by low flutes. In the event that this was an actual service, here the Eucharist would be celebrated. Beethoven labels the section

Präludium

. He has in mind the tradition in which organists would prelude, meaning improvise, during the Eucharist to join the Hosanna to the next section, the Benedictus.

46

So now he creates a searching, chromatic, quasi-improvisation in imitation of an organ. These pages are more a matter of mystery than practical musical continuity: in a sound and texture unique in music of its time, Beethoven conjures a tangible presence of the numinous, in preparation for what follows. Meanwhile, if with the

Dominus Deus

he supplied the chanting priests, here he supplies the church organist. In both respects, as in other parts of the mass, he subsumes the literal rite in the music.

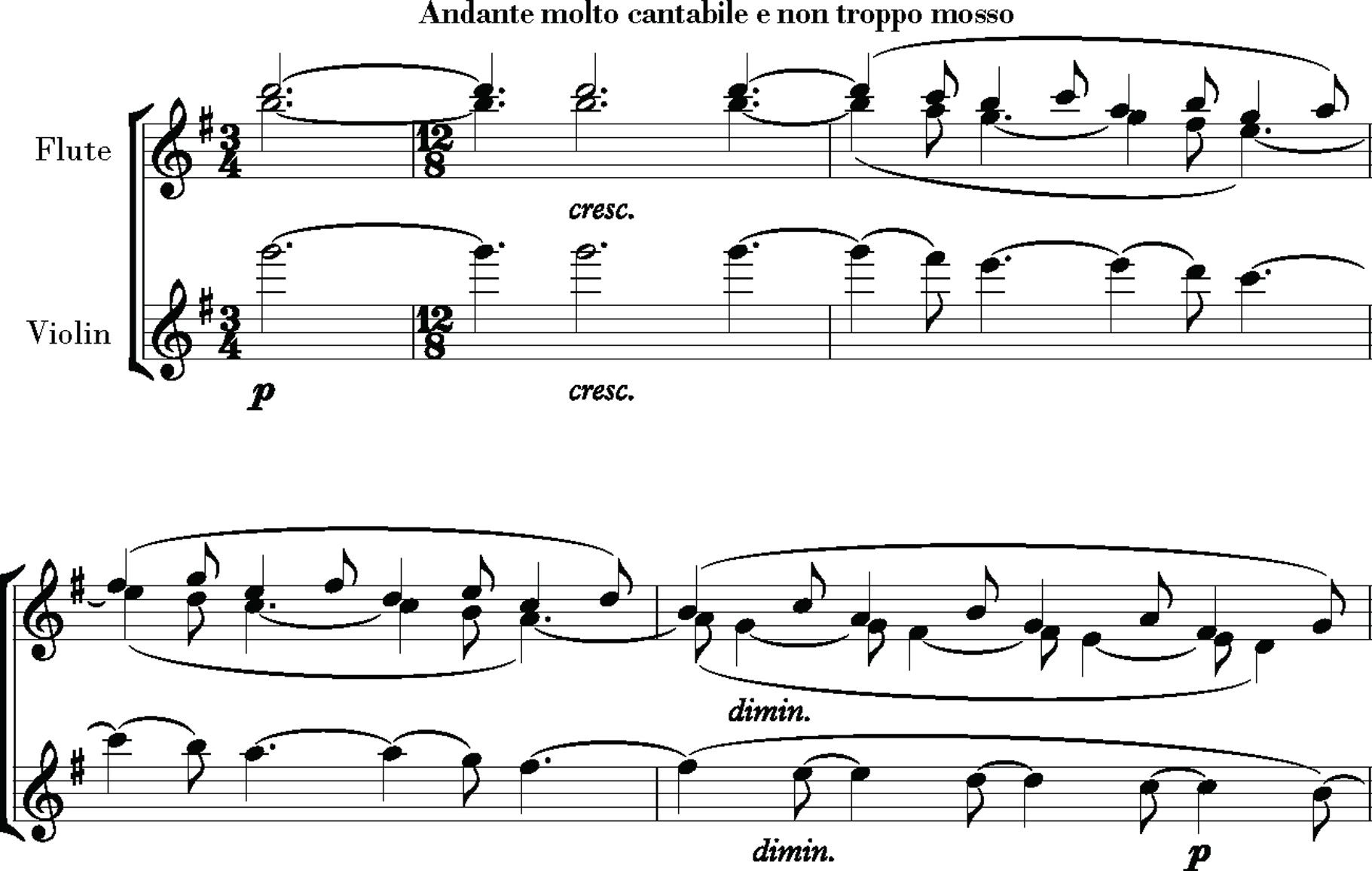

In one of his quietly breathtaking moments, at the end of the

Präludium

, suspended high in musical space, comes another ethereal chord in two flutes and a violin. They begin the Benedictus with a long descent in a lilting, pastoral 12/8, in pure G major.

47

That heart-stopping high chord appears at the moment a candle would be lit on the altar to signify the moment of transubstantiation, when Christ becomes present in the bread and wine.

48

Â

Â

The Benedictus is marked

molto cantabile

, very songfully. Here is Beethoven's evocation and interpretation of the Eucharist, summoning Christ's descent from heaven onto the altar, into the bread and wine. It is a sui generis portrayal of that moment, that mystery, by way of an extended violin solo. Few things in music approach its gentle joy, its long-sustained beauty. Around the diaphanous singing and dancing of the Christ-violin, the choir chants,

Benedictus qui venit in nomine Domini

, Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord. Chorus and orchestra concentrate on the central word,

Benedictus

which goes on and on as an incantation under the endless song of the violin. It is a depiction of the divine presence as a vision of transcendent beauty, like a halo transmuted into sound. It is also the central movement downward in the dialectic of up and down, the human spirit reaching up and divine grace reciprocating. Staying close to a pure, pastoral G major, the music gathers to a tutti at the end of the movement, the violin singing over all and pronouncing the final benediction.

49

Â

Agnus Dei

Â

The strangest and most haunting Agnus Dei written to its time begins in an atmosphere of stark tragedy in B minor, which Beethoven called a “black key.” There are only a few words in this final segment of the Mass Ordinary:

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis. Dona nobis pacem

, Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy upon us. Give us peace. The text comes from the words of John the Baptist when he first saw Jesus: “Behold the Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world.” That image connects Christ, who sacrificed himself for the salvation of humanity, to the sacrificial lamb of Passover. Like any composer of an ambitious mass, Beethoven will have to repeat these words a good deal in order to fill out a substantial final movement. His approach will be to reinterpret the words en route. He breaks the text into the usual three segments, the first and second focused on

miserere nobis

, the third on

dona nobis pacem

. But in the end his Agnus Dei is a personal statement, rising from tradition but stretching beyond it.

Many Agnus Dei sections in masses begin with a gentle, pastoral evocation of Jesus as Lamb of God. Beethoven begins with a moaning, foreboding texture of bassoons, horns, and low strings as accompaniment to the prayer by the bass soloist and men's voices from the choir. The operative idea from the beginning is not Christ as savior but the words

miserere nobis

, have mercy on us, which the music portrays in swelling, funereal tones like a cry of suffering humanity.

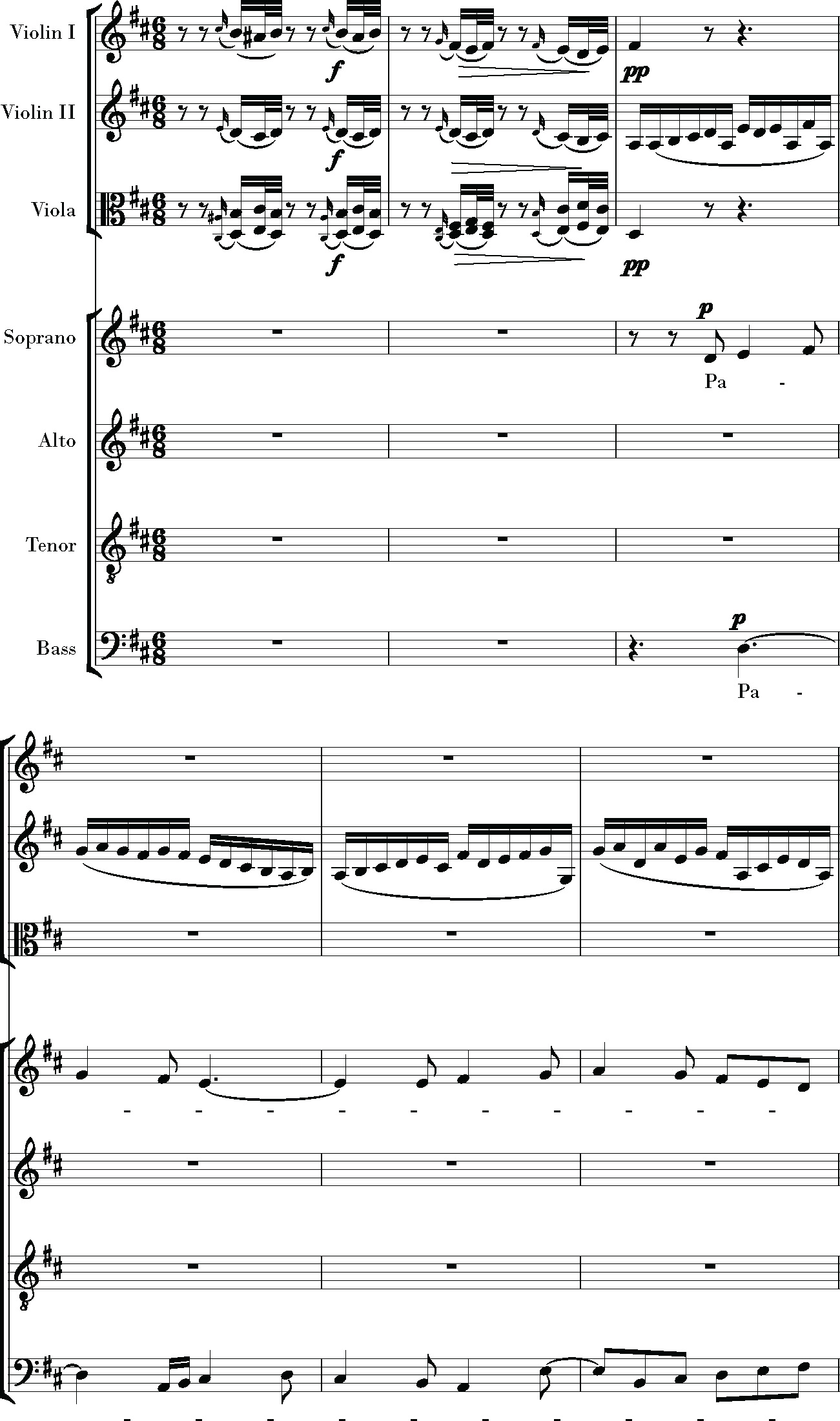

The funeral tread stops, the music harkens.

Agnus Dei

, the choir chants,

pianissimo

. In piercing tones breaking out in the chorus in falling thirds we hear

Dona! Dona nobis pacem!

Give! Give us peace! Gentle music in D major and 6/8 begins, the string figures fluttering like the wings of the holy dove. We have awakened from a dolorous trance to a pastoral scene and a flowing and beautiful

fugato

whose theme sets the single word

pacem:

Â

Â

Â

At the head of this section, Beethoven placed in the score,

Bitte um innern and äuÃern Frieden

, “Prayer for inner and outer peace.” The

fugato

is a pastoral idyll, the sounding image of peace, its meter and flowing lines recalling the violin solo that represents Christ in the Benedictus. The prayer swells, then the orchestra stops and leaves the chorus singing a cappella, with great simplicity and intimacy,

dona nobis pacem

. Beethoven has used this device of dropping out the instruments here and there throughout the mass, but this is the most poignant instance. He wants us to

feel

peace in our hearts and minds. Accompanied by figures dancing up in long ascents and down in descents, the choir sighs,

pacem, pacem

, in floating, archaic harmonies.

The yearning for peace intensifies; the pastoral and prayerful tone gives way to a demand: “Give us peace! Peace! Peace!” The music appears to be building toward a conclusion, a coda. But that is interrupted by something wrenchingly alien: throbbing drums, flurries of strings like gusts of wind presaging a storm. Suddenly out of nowhere there are bugle calls. The soloists take up a cry marked “anxiously”: “Lamb of God! Have mercy on us!” The drums and bugles return,

fortissimo

, under which the soprano's cry for mercy can hardly be heard. In this moment Beethoven explodes the form, in the same way he did with the storm in the

Pastoral

Symphony.

50

Armies have disrupted the rite, destroyed the peace. It is war.

Even this shocking, high-Beethoven intrusion, though, had a precedent. As so often, that precedent was Haydn. In his

Mass in Time of War

, written in the midst of the Napoleonic Wars, Haydn's Agnus Dei is interrupted by trumpets and drums in the same place in the service, and in the same way: mounting drum taps and bugle calls, as if an army were surrounding the cathedral. In Haydn the choir's call for peace finally becomes militant, as does Beethoven's. But Haydn does not shatter the music as violently as Beethoven, does not break the form so completely, does not make the cries for mercy so anguished.

In Beethoven's Agnus Dei, the sounds of war recede, the music recovers. In a chain of falling thirds the chorus again intones,

Dona! Dona! Dona nobis pacem!

51

But the pastoral mood, the idyllic vision of peace, is vanished for good.

Dona

becomes a surging

fugato

that leads to a return of the beautiful, sighing lines on

pacem

, which as before turn into a shouted demand. Yet again that is interrupted by an alien force. War overwhelms the music.

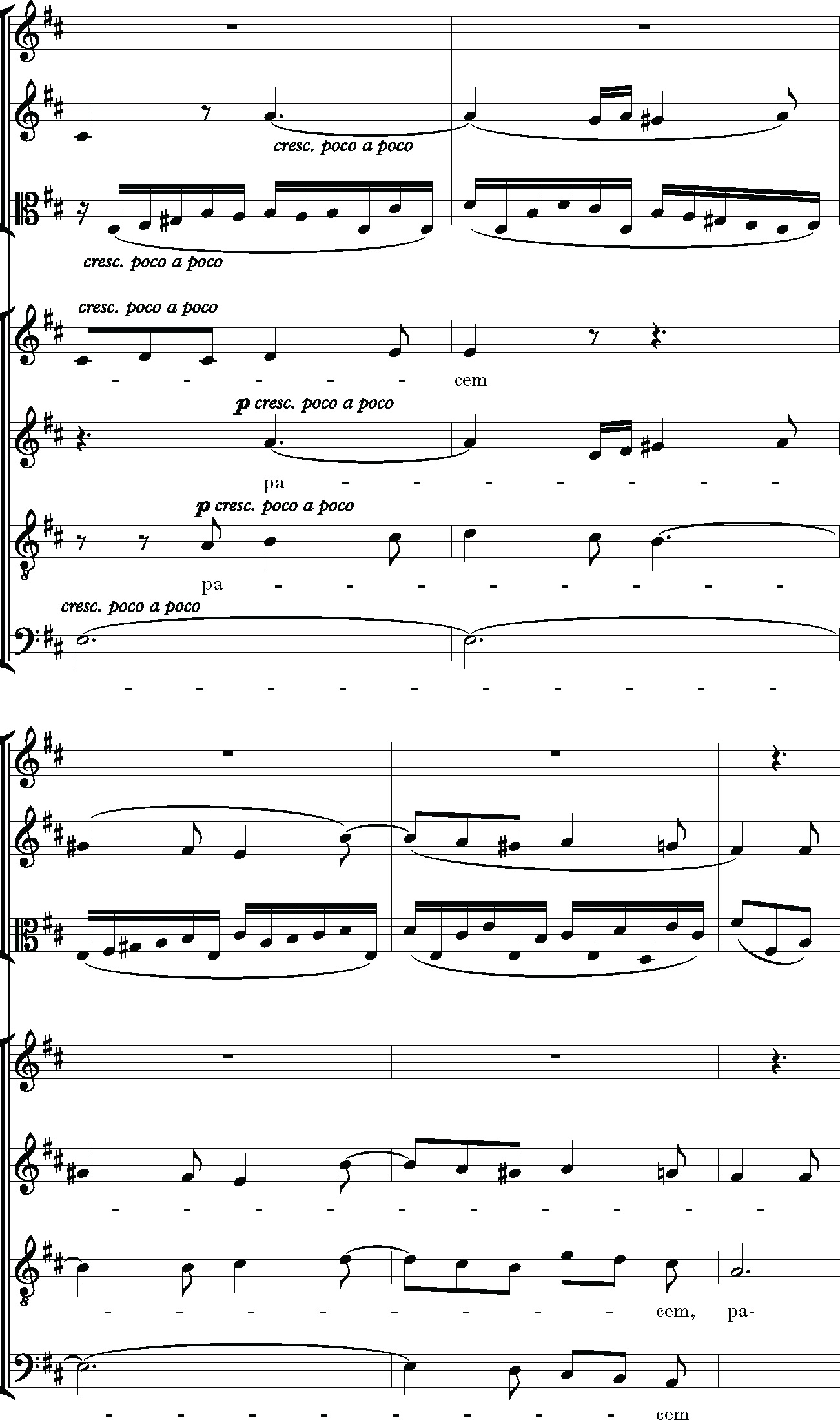

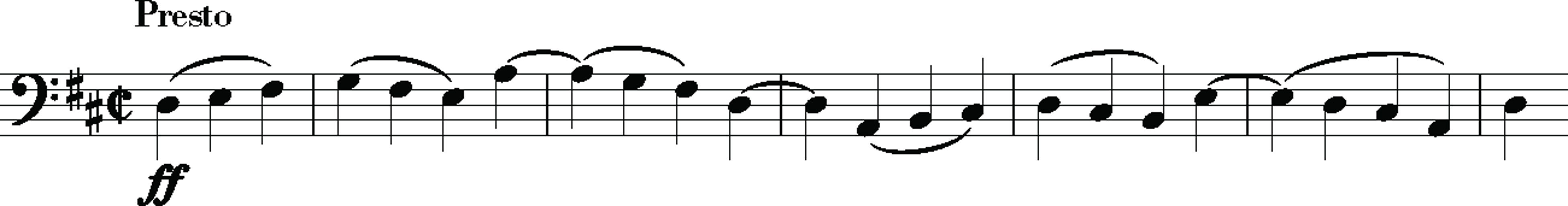

For this section Beethoven first sketched ideas for marches. Then he settled on something more ambiguous: a driving, militant fugue in gaunt colors, the fugue theme a mangling of the pastoral

pacem

theme:

Â

Â

Years before, he wrote over an idea in the

Eroica

sketches “a strange voice.” Here is a truly foreign voice, cold, harsh, and bustling, like a bitter parody of his own heroic style (and this may be the point). In the

Eroica

and other pieces of his middle years, Beethoven hailed the enlightened leader, the benevolent despot, the military spirit. Now for him the military spirit is nothing but destruction. By the end of this section the bugles are raging, the drums roaring, the choir crying

Dona pacem!

in terror.

Now we understand what Beethoven meant by “prayer for inner and outer peace.” The inner peace is that of the spirit. The outer peace is in the world. The fear and trembling in the

Missa solemnis

is not the fear of losing salvation in eternity; it is the human, secular fear of violence and chaos.

For a second time the music recovers. The intonations of

Dona nobis pacem

have gone from pastorally peaceful to demanding to fearful. Now prayers for peace break out again, and the flowing 6/8 returnsâbut it is not a real recapitulation, and still not with pastoral peace. In fact the texture is strangely broken up. The

fortissimo

demands of

pacem! pacem!

seem to fall apart. The music drifts.

Then in the distance, a war drum. The choir prays again:

pacem, pacem

. Again the drum interrupts, farther away, its alien B-flat almost out of hearing.

52

Staccato lines skitter up and down. The chorus makes a longer cry for peace,

forte

but not

fortissimo

. In this last choral phrase of the mass, the sopranos in their cadence again descend only to F-sharp, not all the way to a decisive finish on D. The orchestra gives a scant four bars of climactic music, ending on a staccato D-major chord. There the

Missa solemnis

finds its precipitous finish, in an atmosphere of fragmentation and irresolution.