Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (71 page)

Â

Beethoven was very tired of the Septet, the Quintet, and the first two symphonies being held over him as the unsurpassable masterpieces of his life. After all, he had once said to a publisher in regard to the Septet, “The rabble are waiting for it.” The “commonplaces” cited in the review of the concerto probably referred mostly to the finale, also to the violin figuration and other ideas borrowed from the concertos of Viotti, Kreutzer, and Clement himself.

81

The reviews did not mention how awkward and unviolinistic was much of the solo writing. Beethoven had once played violin and viola, but hardly at a soloist's level. The speed of the concerto's composition carried over into a muddle in the publication, when advice from Clement about the violin writing, which may have been included in the performance, did not get into the published score. In general, the score as the world would know it remained riddled with mistakes and ambiguities.

82

Poorly received in its time, the concerto did not become part of the repertoire until decades later.

Over the years Beethoven produced a number of works that amounted to last-minute, back-to-the-wall professionalism, and in one way and another all those pieces left traces of their haste. When composing at top speed you have to follow your instincts fearlessly on the fly. Beethoven had incomparable instincts and no fear. The miracle is that a few of those pieces, among them the

Kreutzer

Sonata and the Violin Concerto, turned out to be among his most inspired works. On the face of it the Violin Concerto had no reason to be what it was to become well after Beethoven was gone: one of the most beautiful and beloved of all concertos. Its greatness, said a later champion, lay not in its technique but in its cantabile, its singing.

83

Â

For Beethoven, 1806 had been a marvel of a year. In a rush of inspiration scarcely equaled in the history of human creativity, while struggling with crushing physical and emotional pain, he wrote or completed the epochal three

Razumovsky

Quartets, the Fourth Symphony and much of the Fourth Piano ÂConcerto, the second and third

Leonore

overtures and the revised

Fidelio

, and the Violin Concerto. History would confirm each of those works as standing among the supreme examples of their genres in the entire chronicle of music.

20

B

Y THE BEGINNING

of 1807, Beethoven had a backlog of works he was desperate to put before the public. That remained no simple matter in Vienna, where the limited space for concerts was controlled by an obdurate and omnipresent bureaucracy. His published chamber and orchestral music turned up in concerts regularly in Vienna and elsewhere, but there were no royalties for those performances. Public programs were not only his preferred medium for premieres, they were also his most direct way to raise cash.

He could have made a good income touring as a soloist, but his hearing hobbled his playing now, and his health made tours risky. Besides, public performance hardly interested him anymore. He preferred to improvise in private for himself and a few listeners. He still had piano students, still participated in charity benefits, still could rely on his patrons' private soirees to air new chamber pieces. But when it came to ready money, he needed concerts for his own benefit. Securing the best halls, especially the Theater an der Wien, required months if not years of scheming and wheedling the bureaucracy. It was as if he were carrying his works on his back, begging in the street.

Baron Braun had recently resigned from a long tenure as head of the two court theaters. That could only have been gratifying for Beethoven, who considered the baron a nemesis. Braun was replaced by a consortium of nine aristocrats who included Beethoven's old patron Prince Lobkowitz. This group leased the two court theaters and the Theater an der Wien and rented them out for concerts and operas.

1

Beethoven surely expected that the new regime would open its arms to him, but in the spring, yet another initiative for a benefit fell through.

2

He snarled about the “princely rabble” he had to deal with. Early in 1807, he added to his orchestral backlog a new overture called

Coriolan

, used for the revival of the play of that name by his friend Heinrich von Collin. After a single performance in April, Collin's once-popular play sank out of sight, but the overture took off on its own.

In March a brief review appeared in the

Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung:

“Three new, very long and difficult violin quartets by Beethoven, dedicated to the Russian ambassador Count Razumovsky, also attract the attention of all connoisseurs. They are deep in conception and marvelously worked out, but not universally comprehensible, with the possible exception of the third one, in C major, which by virtue of its individuality, melody, and harmonic power must win over every educated friend of music.”

3

At some point the new quartets had premiered in Vienna, likely in Ignaz Schuppanzigh's short-lived public quartet series. The pieces were shaped not just with history in mind but with that virtuoso ensemble in particular. With these quartets, a historic turn in chamber music had begun, away from private amateur performance and toward programs played by professionals for the broad public.

In some six years, between the completion of the op. 18 and the op. 59

Razumovsky

Quartets, Beethoven had gone from a young composer trying on voices and attempting to escape from the shadow of Haydn and Mozart, to an artist in his prime widely called their peer. With those two men as models, in op. 59 he made another medium his own.

Throughout his journey with quartets, Beethoven's partner, champion, and inspiration remained violinist, conductor, and entrepreneur Schuppanzigh, the first musician in history to make his main reputation as a chamber-music specialist.

4

One of the notable things about Schuppanzigh was how little he looked like an artist. Czerny described him as “a short, fat, pleasure-loving young man . . . one of the best violin-players of that time . . . unrivaled in quartet playing, a very good concert artist and the best orchestra conductor of his day . . . No one knew how to enter into the spirit of this music better than he.” The visiting composer Johann Friedrich Reichardt praised Schuppanzigh's clarity and his “truly singing and moving” cantabile playing, at the same time groaning over his “damnable habit . . . of beating time with his foot.”

5

Beethoven teased Schuppanzigh endlessly about his weight and his love of a good time. In 1801, Beethoven presented Schuppanzigh with a piece entitled

Lob auf den Dicken

(Praise to the Fat Man), and he wrote equally tongue in cheek to Ries that “Mylord Falstaff” “ought to be grateful if all my insults have caused him to lose a little weight.”

6

It is recorded that once, Schuppanzigh coaxed his composer to try some Falstaffian entertainment and accompany him to a whorehouse. It did not go well. Schuppanzigh had to avoid the wrathful Beethoven for months afterward.

7

If there had been no leader like Schuppanzigh and no professional quartet at the level of his group, the

Razumovsky

Quartets would have been different piecesâwhich is to say that Beethoven's evolution and the later history of the string quartet would have been different. This portly, silly-looking violinist was the indispensable partner in Beethoven's remaking of the medium.

Another way to put it is that the presence of Schuppanzigh and his men allowed Beethoven to take quartets wherever he wanted to go with them. He wrote the op. 59

Razumovskys

in a rush of inspiration and enthusiasm, probably between April and November of 1806, interrupted by the Fourth Symphony and maybe the Violin Concerto. With the quartets he intended to repeat what he had done with the symphony in the

Eroica:

to make a familiar medium bigger, more ambitious, more varied, more individual, more personal.

8

Once, at Czerny's flat he had picked up the Mozart A Major Quartet, K. 464, and exclaimed, “That's what I call a work! In it, Mozart was telling the world: âLook what I could do, if you were ready for it!'”

9

Now, Beethoven was going to show the world what he could do with the quartet, and he did not particularly care whether the world was ready for it.

The most immediate revolution in op. 59 had to do with the scope of the difficulties. In scale and ambition they are the most symphonic quartets to that time, harder on both players and listeners than any quartet before, even in a medium traditionally meant for connoisseurs. Their progress in the world would be tenuous for years, more so than many of Beethoven's major works of that period. In comparison, it took the

Eroica

only a couple of years to make its point. But there is no mystery in the slow reception of these quartets. The electricity, aggressiveness, and in some ways sheer strangeness of the

Razumovskys

are collectively breathtaking. Even some of their beauties are strange. If in his heart Beethoven remained not a revolutionary but a radical evolutionary, these pieces were still an unprecedented challenge to the public.

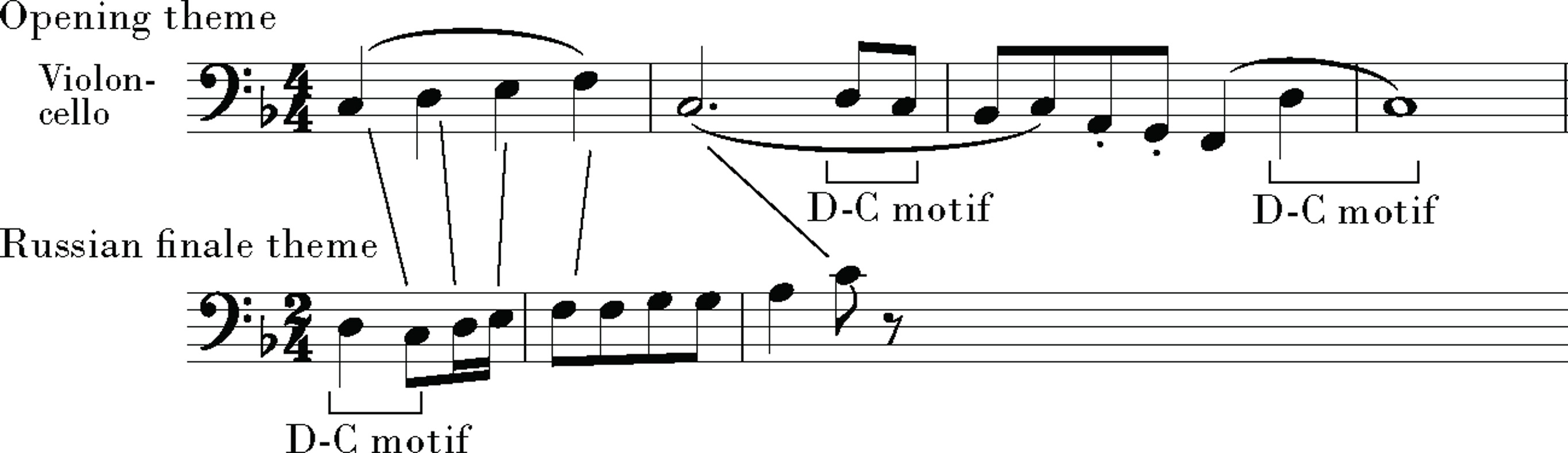

But revolutionary does not always equal loud. The beginning of no. 1 in F major is a quiet pulsation in the upper strings while the cello sings a spacious, flowing, gently beautiful tune rather like a folk song. There is a breezy, outdoorsy quality that will be amplified in the “horn fifths” idea that follows, and later in bass drones in open fifths.

10

At the time, an extended lyric line for the cello under barely moving harmony was simply outlandish. As he had already been doing in his piano sonatas, from here on Beethoven began each string quartet with a distinctive color and texture. Theme and harmony and rhythm are no longer the exclusive subjects of a work; now its very sound is distinctive, as if with each quartet he set out to reinvent the medium from the ground up.

11

The three numbers of op. 59 are a collection of unforgettable characters: one singing, one mysterious, one ebullient.

As he had done in the

Eroica

, then, in the F Major he takes an unprecedented step in giving the opening

Thema

to the cello. He continues his campaign to free the instrument from a life mainly toiling on the bass line. Meanwhile, placing the leading theme in the lowest instrument of the quartet pulls the rug from under the harmony, creating a shifting foundation that destabilizes everything. A melodic cello will be a steady feature of this quartet.

12

As Beethoven began work on the F Major, he pored over his collection of Russian folk songs in order to comply with Razumovsky's commission requirement, picking a tuneful one to use as the theme for the finale. So as in the

Eroica

, he wrote this piece in some degree back to front, basing the opening

Thema

, with its vaguely folk-song quality, on the Russian tune of the finale. That tune is a touch modal, suggesting natural minor on D. What Beethoven picked up to use in the

Thème russe

was mainly its beginning: the first four notes of the Russian tune, CâDâEâF, became the opening notes of his first-movement theme. The first two notes of the

Thème russe

, the falling step DâC, linger throughout as a primal motif.

13

The note D plays a pivotal role throughout the quartet.

Â

Â

The opening presents three distinct, contrasting ideas. But in practice most of the first movement, like the finale, will be involved with the flowing

Thema

, mainly its rising-fourth figure and its 1234 1 rhythmic motif.

14

The second theme, by now rather unusually for Beethoven, is in the conventional dominant key, C major. It extends the rising-fourth scale line to an octave in another flowing theme, the cello again waxing melodic rather than anchoring the bass. Here might be a fundamental conception of this quartet, and not a new one for Beethoven: the idea of

redefinition

, placing the opening idea in a variety of tonal and emotional contexts.

15

(He had played that game with the obsessive little theme in the first movement of the String Quartet op. 18, no. 1, also in F major.)

After a gentle closing theme starting over a rustic drone, connoisseurs would hear the expected repeat of the exposition, returning to the cello theme. But it's a feint, a false return; there will be no conventional repeat.

16

From that point the development spins through a winding course involving some dozen keys, coming to rest for a moment on a section of double fugue in his old admired key of E-flat minorâhere not in its usual poignant-unto-tragic vein but rather driving and intense.

17

The recapitulation is as singular as the false repeat of the exposition. It arrives back in F major not with the expansive cello theme but with the first subtheme, then wanders off harmonically. At length, a grand C-major scale brings in the recapitulation proper but overlaps the return of the cello theme. All this is done to blur the moment of recapitulation. Beethoven wanted the form of the movement fluid, suppressing the formal landmarks to make a more continuous, fantasia-like effect. Finally in the coda of (for Beethoven) modest length, the main theme returns in glory, pealed out in the high violin over droning fifths in the bass, and so finds a stable harmonic foundation at last. At the end there is a quiet touch of modal cadence on the primal DâC before the official

fortissimo

cadence to F major.