Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (79 page)

Â

On December 22 the program began with the

Pastoral

Symphony and finished with the

Choral Fantasy

, the latter cobbled together in one of Beethoven's last-minute marathons. At the first rehearsal the ink was barely dry on the vocal parts. The fantasy has a kind of ingenuous charm. The text, by a local poet, was written to fit the tune of an old unpublished song of Beethoven's called

Gegenliebe

. The lyrics, an ode to music, set forth a train of unions that bestow gifts on humanity. It beginsâ

Â

Flatteringly lovely and fair are the sounds

Â

of our life's harmonies,

and from our sense of beauty there arise

Â

flowers that blossom eternally.

Â

In the next stanzas, “peace” and “joy” are wedded to bring exaltation, “music” and “words” wedded to turn the storms of life into light (once more that echt-Aufklärung image). “Outward repose” and “inward rapture” engender yet more light. The last stanza calls on enlightened humanity to embrace the final union:

Â

And so, noble souls, accept

Â

gladly the gifts of beautiful art.

When love and strength are wedded,

Â

the favor of the gods rewards mankind.

Â

The

Choral Fantasy

takes shape as an ad hoc form, an accumulation: long piano solo, orchestra brought in bit by bit, soloists brought in bit by bit, then a rapturous coda with full choir. The opening solo is a solemn C-minor fantasiaânot at all a tragic C minor. Beethoven improvised it at the 1808 performance and in the published version likely recreated and touched up what he remembered of it. In the piece the piano soloist perhaps represents the spirit of music itself. It begins with massive handfuls of chords striding up and down the keyboard: “lovely and fair are the sounds / of our life's harmonies.” Finally after a stretch of quasi-improvisation, the piano issues a glittering deluge of notes rising from bottom to top, the strings commence a dialogue, and that coaxes the leading theme from the piano. It is a forthright, declamatory kind of tune that since his teens (as in the song

Who Is a Free Man?

) Beethoven had associated with high-Aufklärung humanism. For him that humanistic style had been broadened and intensified by the example of the populistic music of the French Revolution. No less, the theme's folklike style and stein-thumping rhythm evoke a

geselliges Lied

, the kind of exalted drinking song exemplified by Schiller's poem “An die Freude.”

In several ways, Beethoven later remembered this grandiose if middleweight excursion when he came to compose his last symphony and returned to

An die Freude

. For one example, from the beginning of the

Choral Fantasy

there is a sense of searching for something. That destination turns out to be the main theme, its contours suggested in veiled form in the prefatory music. In his last symphony as here, the instruments would find the staunch main theme before the voices enter, and extend it into a series of variations. In the

Choral Fantasy

there is a “Turkish”-style variation; in his last symphony Beethoven remembered that idea too. Meanwhile the second variation is fronted by a dancing flute solo that operagoers at the time would have recognized as an echo of Mozart's eponymous magic flute. In Mozart's

Zauberflöte

and its echo here in Beethoven, the flute represents the magical power of music.

The voices enter piecemeal: a trio of women then a trio of men race through five stanzas until the chorus arrives to drive home the final verse, the one Beethoven most cared about. He extends that text for page after page, homing in on key words and the key idea: the marriage of “love” and “strength,” through whose union in art “the favor of the gods rewards mankind.” There is a hair-raising moment when the choir falls from G major to a brilliant E-flat chord on the word

strength

. Beethoven most especially would remember that chord change in his second mass and in his last symphony, where it proclaims the love and strength of God. That magical chord change echoes Haydn's “Let there be light!” in

The Creation

.

The end of the

Choral Fantasy

, like the endings of

Leonore

and the

Eroica

, rises to unbounded joy: “Götter-Gunst!” (“the favor of the gods!”). Clearly, the text had been put together with the composer whispering in the ear of the poet, because the final stanza amounts to a description of Beethoven's art. In the

Choral Fantasy

that ideal was set forth in a thin vessel turned out in a hurry. It would prove a model for the greater but fundamentally similar work to come. The Ninth Symphony also involves unions and marriages, but on a universal scale: music about things far beyond music.

Â

The Third Piano Concerto had not entirely freed itself of Mozart and the eighteenth century, and it was still the vehicle of a virtuoso. The Fourth Piano Concerto in G Major, op. 58, was entirely

Beethoven's

concerto, in the sense that the

Razumovskys

had declared his mature voice with quartets. The premiere of the Fourth in the concert of December 1808 marked the last time Beethoven played a concerto in public. Maybe in part for that reason, since concertos were no longer a practical part of his portfolio, in this piece he felt unconstrained in remaking the genre, as he had done with other genres, by intensifying its singularity, sharpening its profile as an individual.

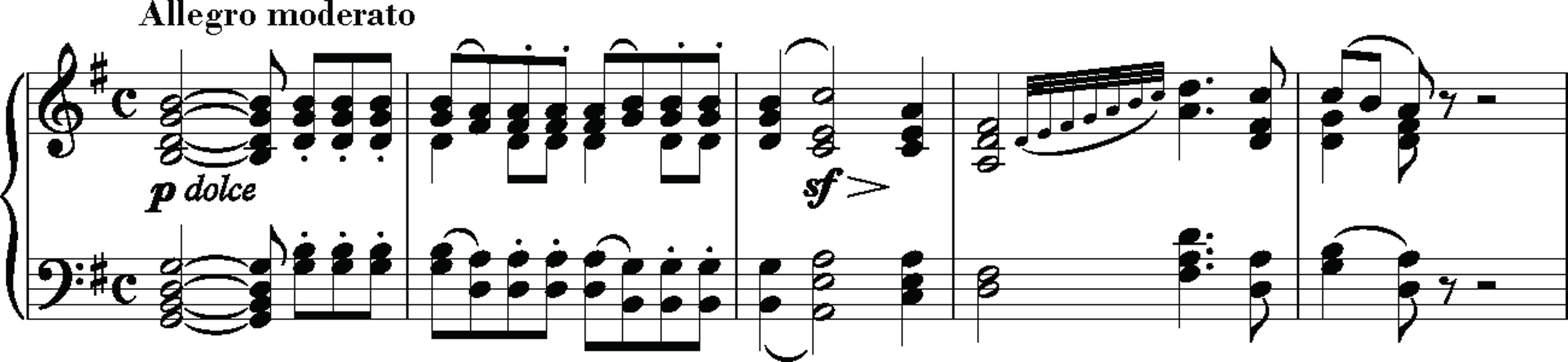

The Fourth Concerto begins with the piano unaccompanied. The soloist is discovered brooding and soliloquizing alone, like a Romantic hero, in a phrase of inward and reverberant simplicity:

5

Â

Â

Its thunder stolen, the orchestra enters quietly but in a very wrong key, distant B major, and not even with the soloist's theme but with a variation of it. Soon the orchestra finds its way back to G major and something closer to the soloist's theme, but from those opening gestures a divide is established that will mark the whole of the Fourth Concerto: soloist and orchestra are on different planes, sometimes complementary, sometimes opposing, sometimes mutually oblivious. Here is the essential gambit of the Fourth Concerto.

6

The solo has its version of

das Thema

, the orchestra has its version, and the two never quite agree on it. In fact, the soloist's version will be heard only once more. So which version of the theme is the “real” one? There is no answer to that question.

Meanwhile the air of brooding nobility that the soloist establishes in the beginning is not otherwise his mood in the first movement, where he is playful, flighty, even mocking. The beginning foreshadows his inner voice, his mood in the second movement, where he and the orchestra will be at odds to a degree that threatens to shatter the integrity of the music.

At the same time the soloist's opening soliloquy establishes a melodic and also a rhythmic motif that will rarely be absent from the first movement. That conception was there from what may have been the first idea for the concerto, in the 1803 sketchbook largely devoted to the

Eroica

. In the wake of his breakthrough symphony, Beethoven's imagination had been racing toward the future. As of 1803 he had found the leading idea for what became the Fifth Symphony, not only its leading motif but the central conception that it would rage on relentlessly. In a sketch he takes the motif down a chain of descending thirds:

Â

Two Beethoven Sketchbooks

Â

Then something struck him. On the opposite page from that sketch he jotted down an idea in G major:

Â

Two Beethoven Sketchbooks

Â

There is the melodic line, virtually intact, of the opening piano soliloquy of the Fourth Piano Concerto. The sketch continues with a passage for orchestra, not immediately in B major, like the final score, but including a jump to B major. Already he had conceived the harmonic dissonance between solo and orchestra.

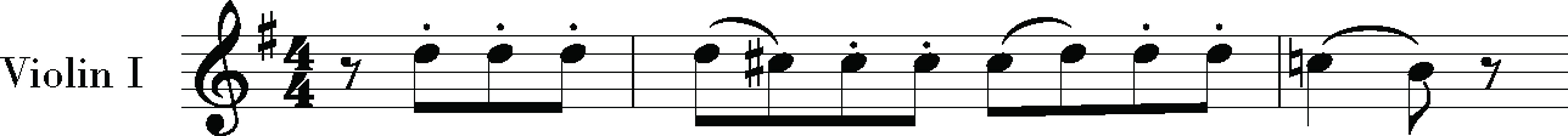

What unites these sketches for a symphony and a concerto is a contrasting interpretation of the same rhythmic motif. The three-note upbeat to a longer note had been a favorite of Beethoven's for a long time, a motif that served him well. There is something innately propulsive about it, the strength of the propulsion depending on how it is presented. In the Fifth Symphony that motif, sped up, is driving and ferocious. Slowed in the first movement of the Fourth Concerto, it creates a gentle lilt, strung along and ending with a sigh:

Â

Â

The commission for the Fourth Symphony and the other rush of works of 1806 broke off work on both the C Minor Symphony and the Fourth Concerto. He picked up the concerto again and had it finished by spring 1807, then returned to the Fifth Symphony. Before the premiere of December 1808, the concerto likely had a private reading or two, hosted by Prince Lobkowitz.

7

Czerny recalled that in the premiere of the concerto Beethoven handled the solo part freely, with a good deal more embellishment than ended up in the published score. That was fitting to the personality of the concerto soloist: when he is expected to echo or to lead the orchestra, he is apt instead to break into glittering roulades. Most especially, this notably flighty soloist is not interested in the military direction the orchestra takes in the A-minor second theme and its lead-in. All this foreshadows the calls and nonresponses that will mark the second movement. Solo and orchestra are on two different tacks, if in the first movement in the same general direction.

The second entrance of the soloist, in the normal concerto position beginning the second exposition, hints at his attitude in a series of tritones, CâF-sharp, the old

diabolus in musica

Beethoven had singled out as early as the op. 1 Trio in C Minor. The implication here is not tragic or demonic but contrarian: at his second entrance in the piece the piano declares neither his own version of

das Thema

nor the orchestra's but rather offers up a bouquet of flowers. From that point on, their interaction is a series of frustrated expectations, the soloist remaining neither a follower nor a leaderâthough he does manage a more embroidered version of the orchestral

Thema: