Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (81 page)

Â

A rhythm, a shape, a dynamism moving from darkness to light, from C minor to C major, a determination to knit the piece tightly from beginning to endâthese are essential conceptions of the Fifth Symphony. They are not different in kind from what Beethoven had done before. For that matter, they are not different in kind from Haydn and Mozart. They are different in intensity and concentration, in force and fury, in how thoroughly they permeate the music. Now instead of using a rhythmic motif as a background device for moving the music forward, Beethoven places the motif in the foreground as the substance of the music. To the ears of the time the result was strange and breathtaking in a way that later listeners, for whom the Fifth became ubiquitous in the repertoire, a kind of sacred monster, would hardly be able to reclaim.

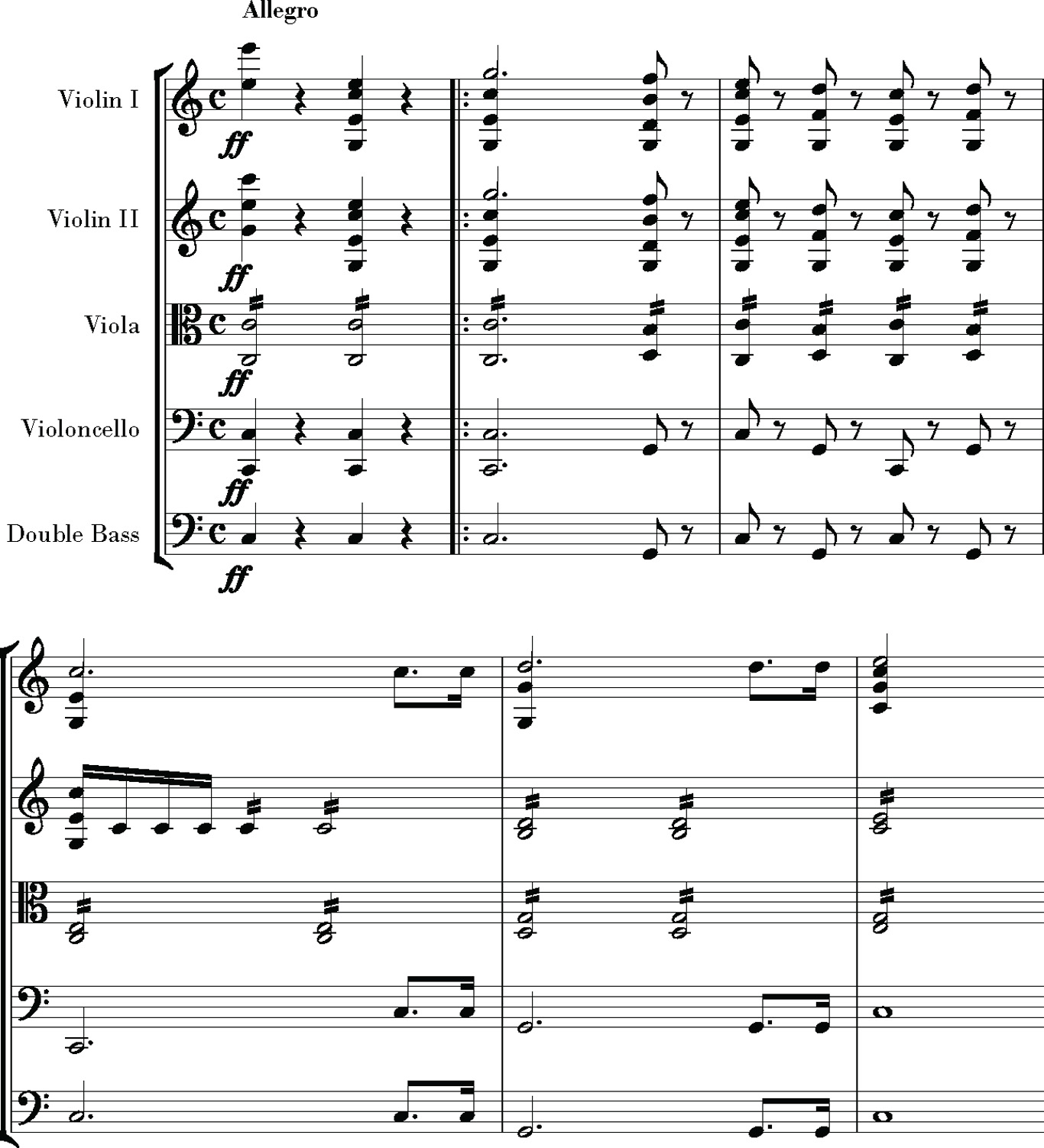

The blunt simplification of gesture and sound, the monorhythm, and the simple, stripped-down sonata form of the first movement are shaped to convey something ferocious, inescapable: a force of nature, a relentless drumming of fate. Once again Beethoven shows off his incomparable skill at creating and sustaining tension, one of the hardest things to do in music that has to be worked out over months and sometimes years, penned one note at a time.

The singing second theme is bound to the basic ideas. It is introduced by a pealing horn call on B-flatâE-flatâFâB-flatâthe S shape, the intervals expanded from the beginning. Those notes in turn are used as scaffolding for the second theme:

Â

Â

As has been noted, the

phrasing

of that theme is 2-3-4 1, augmenting the primal rhythmic tattoo. The basses under the second theme inject the original tattoo. The primal figure gets into everything: the rhythms on the surface and the phrasings under the surface.

To say it again: For Beethoven the elements of a piece are not just abstractly logical, they are also expressive, full of feeling and meaning from the level of the individual gesture to the whole of the form.

16

In the first movement he intensifies the effect of something inescapable by a simplification of form: only the primal motif for first theme; the short, contrasting second theme in the usual key, the relative major; in the development not a wide range of keys (mostly G minor). No subthemes, no formal ambiguities, a regular recapitulation. (The whole of the symphony is one of his shortest, some thirty-four minutes, but its impact makes it feel much longer.) The simplification of outline is part of its fatalism. It is as if there were

no way out

of the dictates of the form.

So the form is simple and regularâexcept for one giant peculiarity: the retransition to the recapitulation. Ordinarily for Beethoven that is a point of high anticipation. Instead, here at that point the music drifts into a fog, vague pulsations of strings and winds calling to one another. The shouting horns that herald the recapitulation burst out of that fog. The haze will return in the movements to come. Another unusual element in an otherwise straightforward recapitulation is a brief, poignant oboe soliloquy that interrupts the flow. The oboe appears like an individual standing frail and alone, singing in the midst of a storm. Here again logic and emotion work together: the oboe retraces the descent from G to D in the first four bars of the movement; at the same time, in its flowing descents the soliloquy foreshadows the themes of the second movement.

The final novelty is an immense coda, equal in length to the exposition and to the development. As he had done in the

Waldstein

and the

Appassionata

, here again Beethoven manages the feat of ratcheting enormous tension still higher; the music becomes an all-consuming rampage. The climax, strings and winds again calling to one another, is a sweeping downward scale tracing a sixth. That downward sixth, from E-flat to G, will become a refrain in the second movement. So the coda is at once an intensification of the drama, a thematic completion, a continuation of the development, and a foreshadowing of the slow movement.

17

Yet the coda generates so much energy that the curt final chords cannot resolve the tension. As in the

Eroica

and the

Waldstein

, resolution and completion will have to wait until the finale.

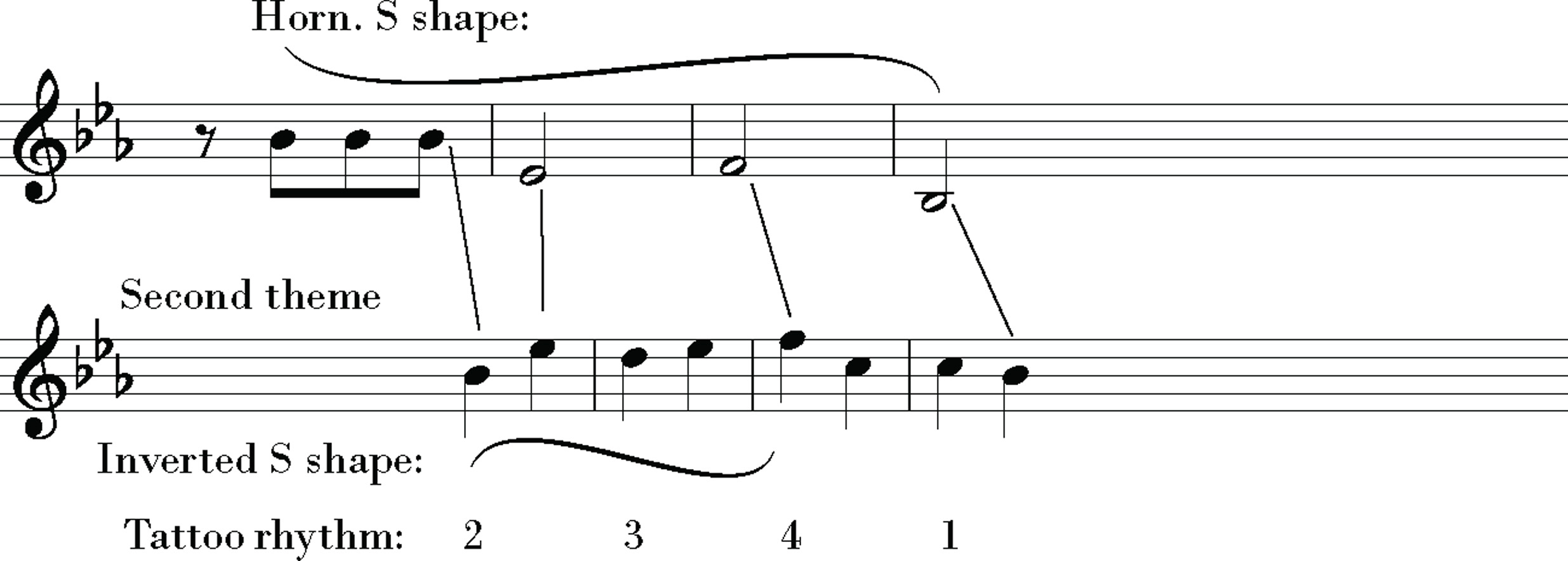

After the tempest of the first movement and its climax in the coda, the second movement arrives suddenly, in medias res, its lilting theme in the cellos like an oasis and a solace. (Its key of A-flat major served the same function of release from C-minor tension in the

Pathètique

.) Beethoven labeled the first sketch of the main theme Andante quasi minuetto. For all its gentle charm, the cello line has a strangely angular configuration, partly because it is built in several ways on the scaffolding of the S shape, the intervals expanded (see earlier example). In the second movement the driving tattoo from the opening bars is tamed. On the first page of the symphony it is a driving upbeat figure: &-2-& 1. In the second movement it often forms a more flowing figure starting on a downbeat: 1-2-3 1. In bars 14â16 of the second movement we hear the figure in both forms at four speeds, underlying a phrase of ineffable tenderness that echoes the descent from E-flat to G in the coda of the first movement:

Â

Â

In its form the Andante con moto is lucid but singular: alternating double variations, first on the cello theme with its tender refrain, then a B theme that begins quietly in A-flat and then flares into a pealing, brassy C major. Eventually that C-major fanfare will be transformed into the first blaze of the finale. (In sketches Beethoven first made it quite close to the opening of the last movement, then tempered the resemblance to a premonition.)

18

The fog of the first-movement retransition turns up again; at the end of each pair of variations, the music retreats into a mist, as if it has lost its thought. The first variation on theme A is drifting and beautiful, like a fair-weather cloud in summer. But near the end, after more exchanges of the two themes, the final variation of theme A is a strange staccato march of woodwinds, in affect somewhere between parodistic and ominous. Both those qualities foreshadow the next movement.

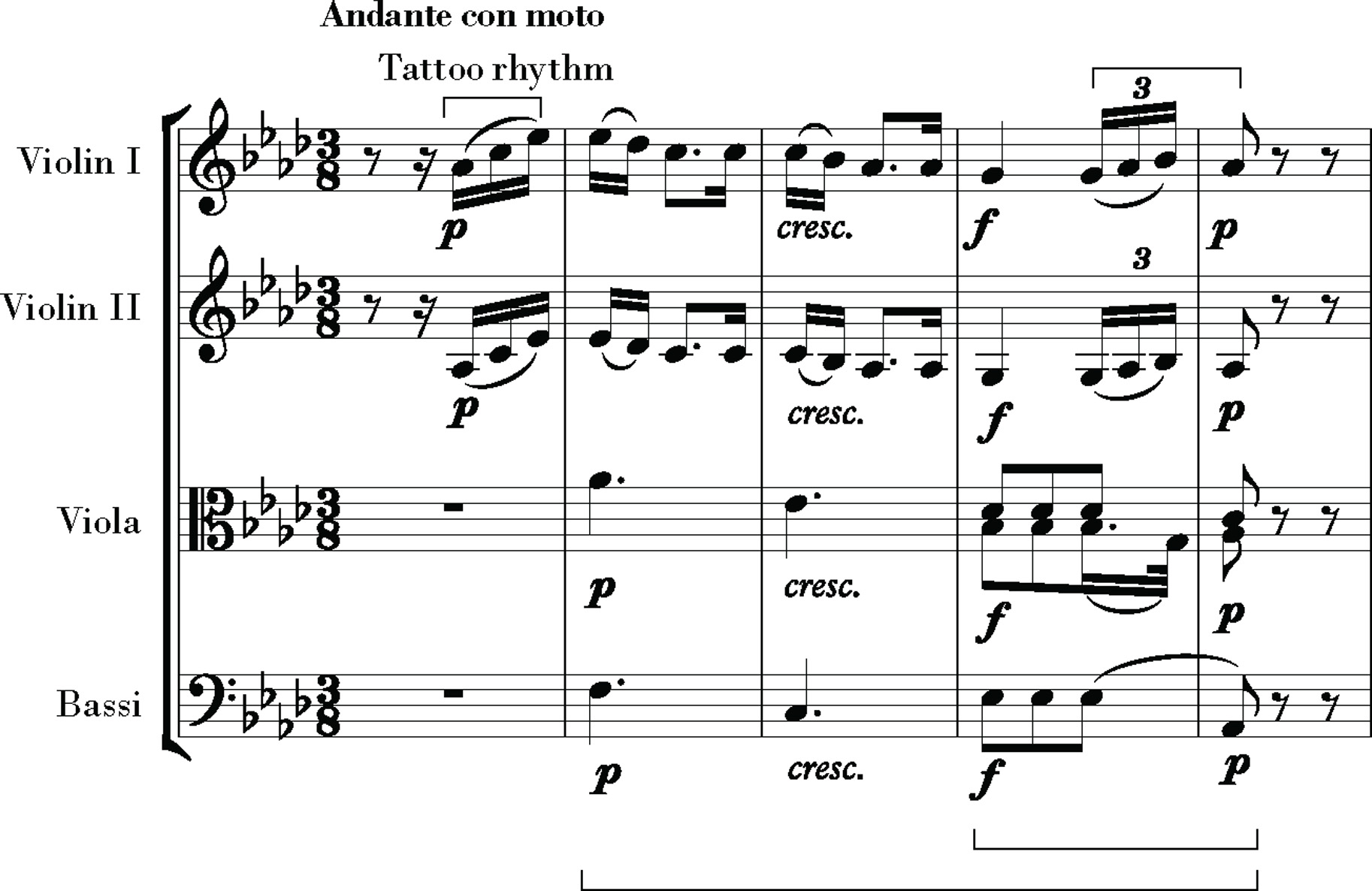

That movement, in C minor, is a scherzo in meter and tempo and form (scherzo-and-trio), but in tone hardly the usual playful outing; it is tinged with Beethoven's C-minor mood. There is a whispering bass oration, then a peal of horns and answering winds on a sternly aggressive theme:

Â

Â

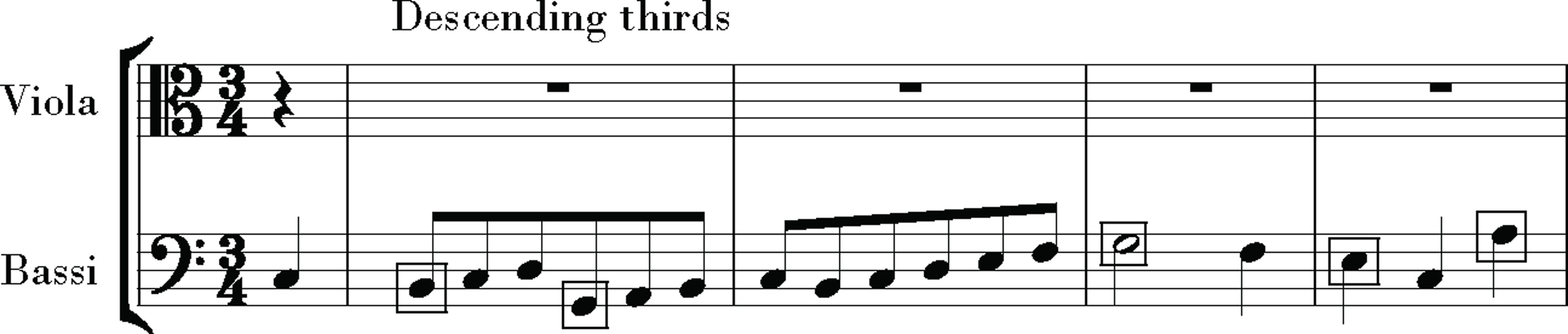

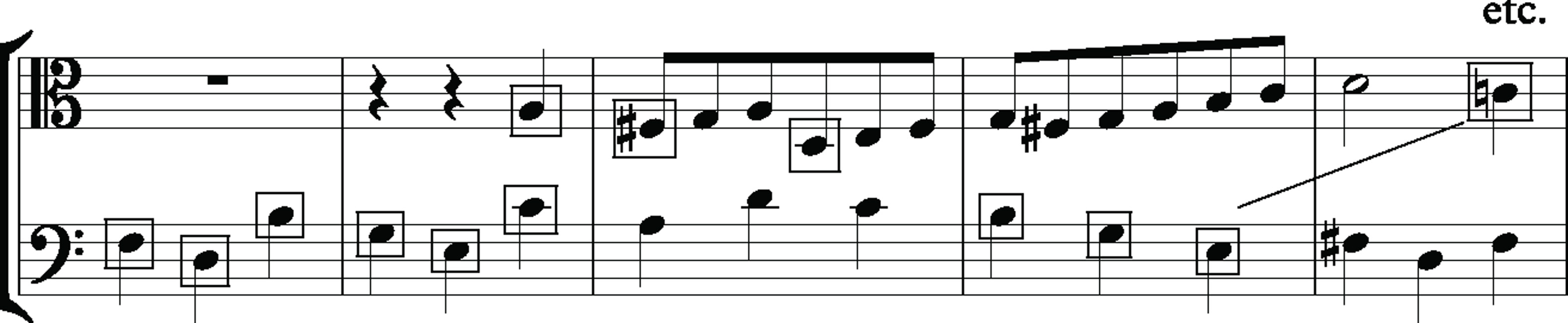

That theme is another expression of the 1-2-3 1 version of the primal rhythmic motif, and its C minor returns the music to something like the fateful tone of the first movement. But now the moods drift, there is no monorhythm, no sense of something inescapable. So the first part is capable of giving way to a jovial C-major trio whose main theme strides continually down in thirds:

Â

Â

Â

There is a farcical moment when the basses set out on a racing line and stumble, stop, try it again, stumble again, and finally get it right. Besides providing a comic interlude in the expressive narrative, there may be a private joke here: Beethoven retaliating against perennial grumbles over the difficulties of his bass parts. The trio also previews leading melodic ideas of the finale, so it amounts to a prophecy of the triumph of C major.

Here ambiguity creeps in. The C-minor nonscherzo comes back altered, the bass theme turned into a staccato parodyâthe same thing that happened to the main theme in the previous movement. Then, as in both earlier movements, fog rolls in, truncating the varied repeat.

19

The music falls into a mysterious texture of strings and thrumming timpani.

20

Its ancestor is Haydn's “Chaos,” which prepares the emergence of light.

21

From that quiet chaos bursts the C-major blaze of the finale, whose essence lies in the brass. Its style recalls the simple and straightforward manner of French revolutionary music, the feeling like a cry of freedom and release. Enhancing the weight and flexibility of the brass, to the horns and trumpets Beethoven adds trombones for one of the first times in a symphony.

22

Their throaty blare gives the finale not only weight but a distinctive coloration. To extend the orchestra's compass upward, he adds a piccolo.

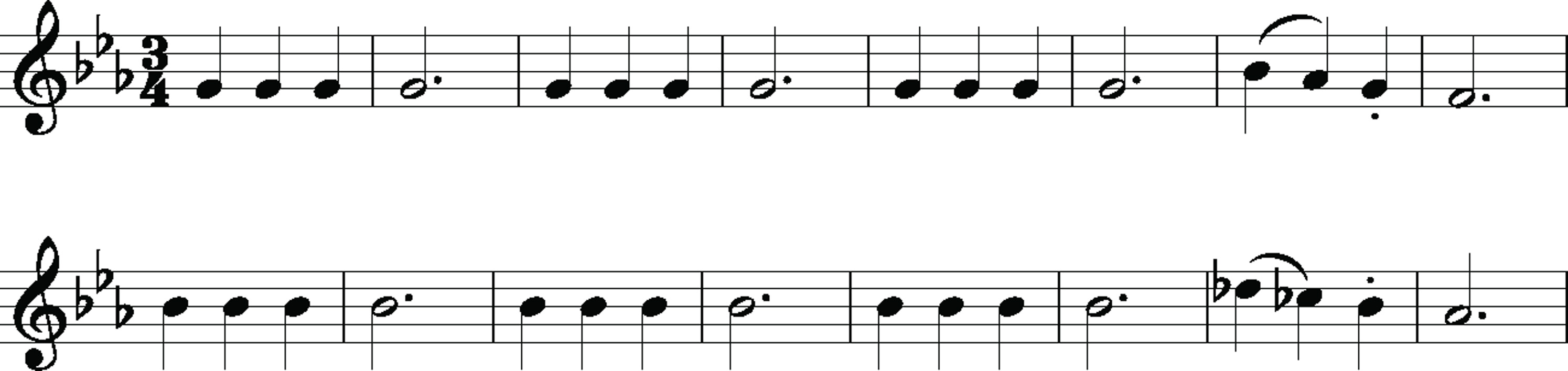

Call the finale a triumphant recomposition of the first movement, without the fateful monorhythm but with the same kind of relentless intensityânow a joyful intensity. The materials of first and last movements are the same. The primal rhythmic tattoo is first enfolded in scales dashing upward. The main motif of the movement itself is a three-note up-striding figure, prophesied in the brass theme of the second movement:

Â