Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (82 page)

Â

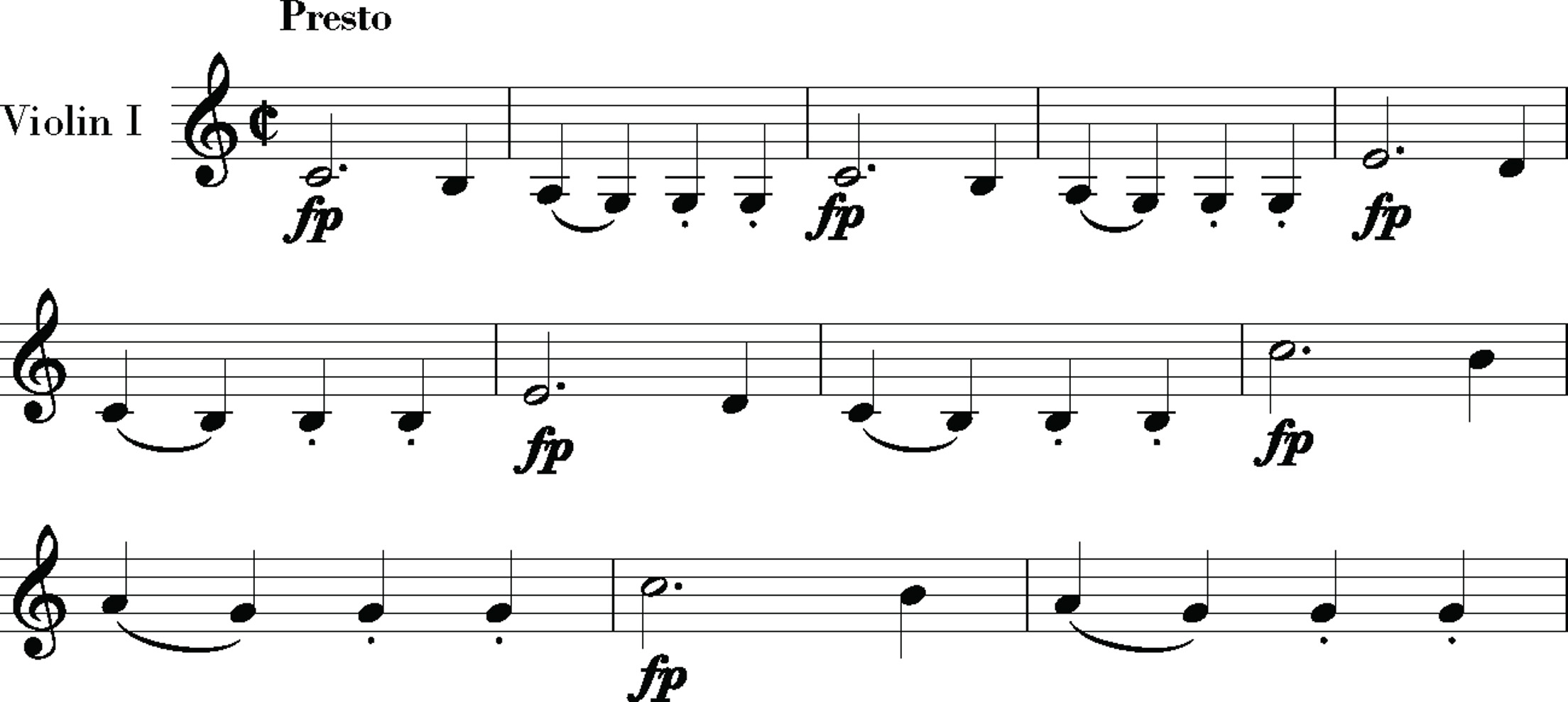

The &-2-& 1 and 1-2-3 1 motifs turn up in various avatars, likewise the S shape (see earlier example).

23

Like the first movement the layout is straightforward sonata form, but with more variety of themes and keys. The development starts loud, calms down, builds with mounting excitement toward the recapitulation. But at the moment of return, when we expect the brass to break into their heroic shout, abruptly the music pulls back into a shrouded place, as it did several times in the earlier movements. What happens then is beyond anticipation: the comic/ominous theme of the third movement returns in a staccato tread. The effect is much like something Beethoven had done years before: the racing finale of the op. 18 B-flat Major Quartet invaded by

La Malinconia

. This time there is no label on the page, and the effect of the nonscherzo invading the finale is ambiguous. But in both pieces the gist is the same:

The joy and the triumph will not be unsullied, not be complete

. Beethoven knew that triumph is never final. The demon can always come back.

24

After a truncated recall of the foggy transition to the finale the recapitulation erupts in full force, as if the interruption had never happened. In the coda, Beethoven wanted, as he had done in the first movement, to raise the intensity even higher. There the intensity of fate, here the intensity of joy. He returns to the monorhythm of the first movement, in a steadily ascending figure. Here is the final transformation of the primal rhythm: in the beginning of the symphony it was a fatefully falling figure, here a triumphantly rising one:

Â

Â

The effect is similar to the end of the

Eroica

, but the implications are quite otherwise. The

Eroica

adumbrated a story of a hero's victory and the blessings he brings the world; it conveyed that narrative in complex forms and a welter of ideas. The Fifth tells a story of personal victory and inner heroism, painted in broad strokes on an epic canvas. The ecstasy at the

Eroica

's end is humanity rejoicing. The ecstasy at the end of the Fifth Symphony is a personal cry of victory.

That journey from despair to victory was Beethoven's own. As his mother taught him: without suffering there is no struggle, without struggle no victory, without victory no crown. But Beethoven was not a Romantic, and he was not mainly concerned with “expressing himself.” As in all his music, even if there were echoes of his own life the goal was not autobiography but a larger human statement. The

Eroica

exalts a benevolent despot as a human ideal. The Fifth Symphony makes that heroic ideal individual, inward, but no less universal. The

Eroica

exalts the conquering hero as bringer of a just and peaceful society. The Fifth proclaims every person's capacity for heroism under the buffeting of life, a victory open to all humanity as individuals. The later course of Beethoven's music amplified that journey inward. As he would put it one day: through suffering to joy.

25

Â

The Fifth would stand as a thunderclap in musical history. With the Sixth Symphony in F Major, op. 68, Beethoven took a turn equally drastic, as drastic as any in his career. On the face of it, the Sixth echoed something he had done before: follow an aggressively challenging work with a gentler and more popularistic one. The Fifth is ferocious and has no stated program. The Sixth is a sunny walk in the fields, equipped with a title:

Pastoral

, each movement with a subtitle relating to a day in the country. But again it is a matter of degree, of the intensity of the contrast: the Sixth Symphony is the anti-Fifth.

From older sketchbooks Beethoven picked up some sketches toward the

Pastoral

and finished it in spring 1808, directly after the Fifth, in the middle of trying to extract another benefit concert from the court bureaucracy. In the

Pastoral

we see one of the more transparent demonstrations of how he turned an idea into sound: the idea inflecting melody, harmony, rhythm, and color. His inherited formal outlines he cut and shaped and sometimes broke to fit the idea.

The Sixth's first germ was perhaps a sketch conjuring the sound of a brook. His thought process evolved toward the idea of an orchestral work about a visit to the country. It was not to be an overture or a single movement or some kind of free-form orchestral fantasia. It was to be a real symphony: a “pastoral” symphony. The pastoral mode had been done many, many times before. Like the popular pieces picturing battles, pastorals were largely a trivial genre. Handel, however, had placed a lovely interlude called “Pastoral Symphony” in his

Messiah

. More to the point, Haydn had woven natural scenes and sounds into his

Creation

and

Seasons

. History had accumulated a repertoire of conventional pastoral gestures, such as bagpipe drones, folk tunes, simple harmonies, lilting music in 6/8 or 12/8, country dances, birdsongs, placid keys like B-flat major and F major, an air of gentleness and artless simplicity.

26

How, Beethoven reflected, can you map these kinds of effects and moods into the forms and the movements of a symphony? How can you set down the necessary clichés and not have them add up to a cliché?

The idea he settled on was this:

Each movement will be a vignette from a day in the country

. The symphony would depict one midsummer day, morning to sunset. No conventional “four seasons,” no clever incidents, no pictures. Only vignettes and feelings. He jotted on a sketch, “effect on the soul.” He searched for corollary ideas to fill out the overriding idea. He called the first movement “Awakening of cheerful feelings on arriving in the country.”

27

The city gives way to fields and woods; the feelings are rapturous. The listener is, say, riding in a cart, flowing into the beauty and the warmth, the timelessness, the holiness. The key would be F major, the same that Haydn used for pastoral movements in his oratorios. But the 2/4 tempo would not raceânot like the Fifth. Everything the Fifth was, this would be the opposite.

The first movement will follow the usual outline with its themes,

Durchführung

, and so on. But no drama, no feverish excitement this time. No

fate

. Glorious sunshine, not even a passing cloud. No suffering, no triumph, but fulfillment. Themes like folk tunes, a shepherd's pipe, flowing rhythms. Minor keys all but banished (only three bars in minor), scarcely even a minor chord. Most of it soft. A peaceful development.

28

Waves of exaltation passing over the soul. As Beethoven said: every tree and hill shouting,

Holy! Holy!

Ultimately it is to be about stepping into holiness, about beholding God.

For the slow movement he returns to the sketch from years before, trying to capture the sound of a brook in notes. He calls it “Scene by the brook.” Flowing, babbling. A sense of endlessness: the first movement the arrival; the second movement the being there, the trance, the drifting ecstasy. Not a contrast to the first movement but a fulfillment of it. The warmth of low strings with divided cellos.

A symphony needs a scherzo or a minuet. Call this one a country dance in the outdoors, “Merry gathering of the countryfolk.” A dance in the late afternoon, after work in the fields. He remembered an idea in 2/4, a quote or imitation of a country dance jotted in the sketchbook of the

Eroica

. That serves as a trio. He remembered a country band he saw at a dance, the oboist who couldn't find the downbeat, the sozzled bassoonist who kept dozing off and awoke now and then to blat out a few notes. They go into the scherzo.

29

He had vowed to avoid pictures and events, but all the same there had to be a storm, a staple of the pastoral genres. This would be a good one for a change. He'd show them how violence was done, not like the polite primal “Chaos” in Haydn's

Creation

but rain and lightning and thunder. (Still, the storm in the “Summer” of Haydn's

Seasons

would be a model.)

30

Kant said that the works of God in the world are the visible sublime, but that we can conceive them only inside ourselves, as feeling.

Effect on the soul

. A

real

storm. All the harmonies unsettled. Bring in trombones!

But how would all this thunder and lightning fit into a symphony? A separate movement? That had been done a thousand times. What about this:

The storm interrupts the repeat of the scherzo

, as if it has broken up the dance and sent the peasants running for shelter. But how to make that work? What could make a transition from a jolly dance to raging chaos? Well, after all . . . a storm

happens

. There is no logical transition in God's nature, so why should Beethoven have to make a transition? The storm interrupts the form just as it interrupts the dance. The storm

breaks

the form.

For the last movement, the storm is over, the sun comes out, God smiles. Beethoven jotted on a sketch, “O Lord we thank thee,” but the published version leaves that implicit.

31

“Shepherd's song. Happy and grateful feelings after the storm.” The idyll returns. The folk emerge into the sunset with relief and thanks. He wouldn't make it the usual fast finale, and certainly not a heroic one. This called for thankfulness, not dancing. A prayer of thanks in the glow of the sunset after the storm. Start with an alpenhorn sounding in the distance, calling in the herds.

32

Not so slow as an

adagio

, but flowing and peaceful and beautiful, in 6/8, the old pastoral meter, almost all the movement in F major.

Now find the notes

. Throughout the symphony he wanted listeners to sense the consuming beauty, peace, and holiness of the country, feel it not just in the senses but in the soul. The rhythms needed to be gently loping like a horse cart, or babbling like a brook. Long repetitions of figures as in the Fifth, but to the opposite end: there fierce and fateful, here a trance of beauty. Themes like folk songs and country dances. In the harmony use more peaceful subdominants than dynamic dominants. Let them feel the timelessness, hear the shepherd's pipe in the oboe. The sound of the orchestra spacious and warm, not hard and muscular like the Fifth or monumental like the

Eroica

. The feeling simple, flowing and piping and singing. Lots of woodwinds, not much trumpet. Save the trombones for the storm. The warmth of violas and divided cellos. Alpenhorn calls in the winds and horns. A portrayal of sensation and emotion without, however, the sensation of boredom. How to make the notes do these things, be that simple without boredom, was very, very difficult. Beethoven had always known this: the simpler, the harder. But difficult was good. Make it unmistakably pastoral but

new

.

33

Â

In terms something like these the

Pastoral

Symphony took shape, flowing from its fundamental idea: what Beethoven's time called a “character piece” and a later time called a “program piece.” For him that meant not a detailed portrayal of episodes but broader scenes and feelings, as in his funeral marches, which were not marches in detail but moods (still, with trumpets and drums and cannons). Here the point was not to paint pictures (though in fact he painted them) but to bring the listener to a particular kind of reverie, an exaltation that he knew intimately. Years later he wrote in a diary, “My decree is to remain in the country . . . My unfortunate hearing does not plague me there. It is as if every tree spoke to me in the country, holy! holy! / Ecstasy in the woods! Who can describe it? If all comes to naught the country itself remains . . . Sweet stillness of the woods!”

34

And in a letter: “Surely woods, trees, and rocks produce the echo which man desires to hear.” He meant an echo of all creation, a yearning for the divine.

These yearnings and intuitions rose from the Aufklärung, which saw nature as the revelation of the divine and science as the truest scripture. In that respect Beethoven had a more immediate inspiration for his ecstasies and his symphony in what may have been his favorite and most-read book:

Reflections on the Works of God and His Providence Throughout All Nature

. Its author was Rev. Christoph Christian Sturm, a Lutheran theologian and preacher. Published first in 1785, Sturm's book was widely read, reprinted, and translated. In a series of 365 meditations, one for each day of the year, keyed to the seasons, Sturm tours much of the day's scientific knowledge while turning each entry into a little homily on the grace and goodness of God. For an example, here is Sturm's paean to the seasons:

Â

If we examine the works of God with attention, we shall find . . . many subjects which may lead us to rejoice in the goodness of the Lord, and to exalt the miracles of his wisdom. During the budding spring, the bountiful summer, and the luxuriant autumn, when Nature . . . assumes her gayest and most splendid robes, hardened and callous, indeed must be that heart which does not throb with pleasure, and pulsate with gratitude, for such choice gifts. But when the north wind blows, when a biting frost stiffens the face of the earth, when the fields . . . present one wild and desolating view, then it is that men . . . will sometimes forget to be grateful. But is it true that the earth at this season is so utterly destitute of the blessing of Heaven . . . ? Certainly not.