Black Pearls (3 page)

Authors: Louise Hawes

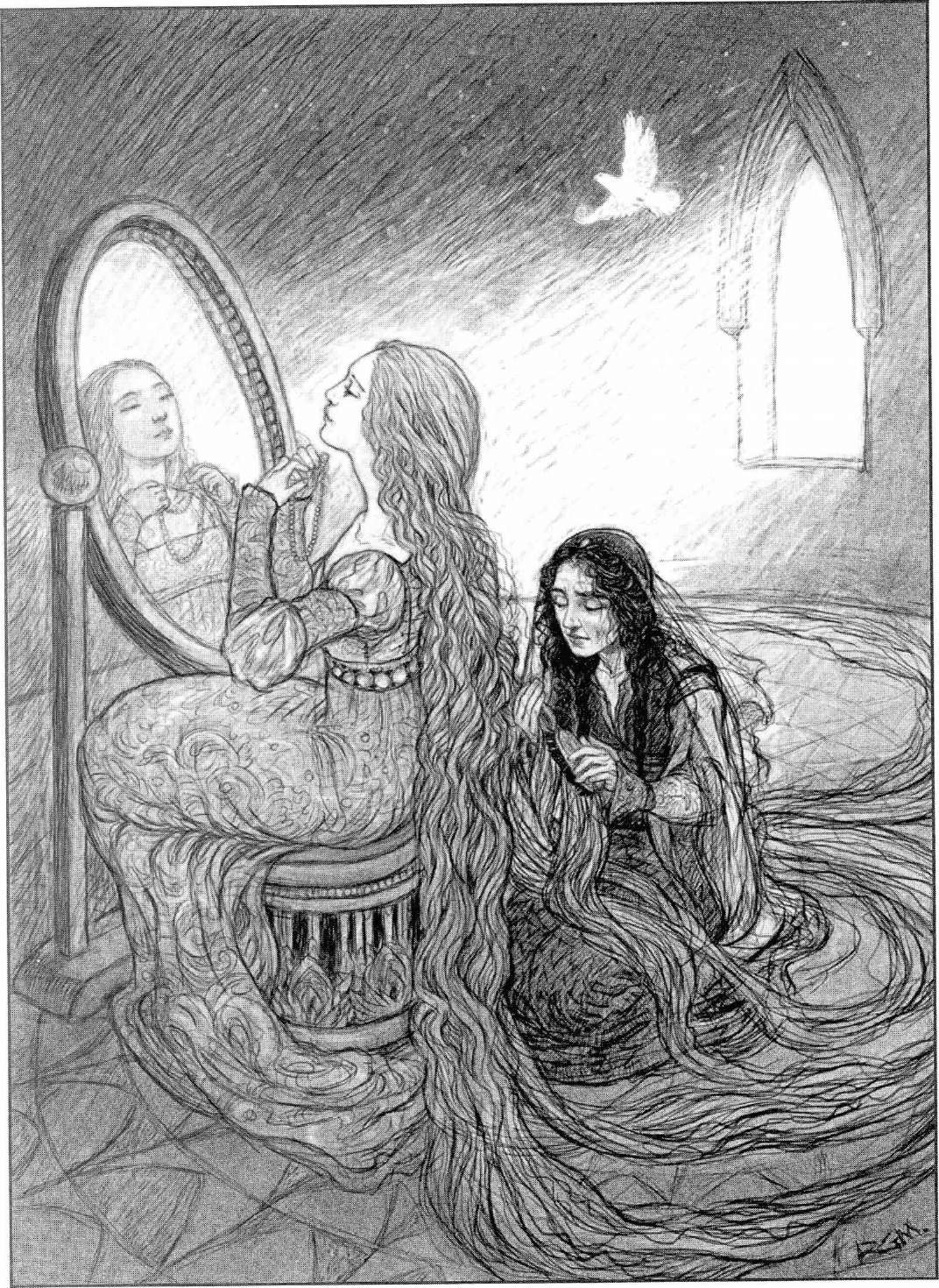

When she did, the girl's rapturous smile was worth every ache in Tabby's back, every morning spent on stiff knees. "Oh!" Rampion stared at her reflection in the looking glass they had bought at Bridley the year before. "It is the loveliest thing I have ever seen!" She watched the play of light on her new necklace, staring as if spelled into the glass. "Will you brush my hair the way you used to, Mother? I feel as though I am quite outshined!"

Rampion unpinned her hair, and Tabby was astonished to see

how long it had grown. Reaching past her ankles, it rolled across the floor in frothy golden waves. The bristle brush was found and Tabby sat in the light from the window while, weak with fondness, she worked through the tangled locks, down and down.

The evening Tabby found the upside-down cross nailed to their door, she did not tell Rampion. She had come home late from serving at a burgher's saint's day feast and was so tired, she failed to notice the two branches tied together and fastened just above eye level. It was the smell of the blood splashed across them that made her stop, made her draw back and cover her nose. Once she had tiptoed upstairs and seen that her daughter still slept, she snuck back down the stairs again, tore away the hateful token, and cleaned the door until no trace remained.

Tabby was well aware that she courted such hate by working in town, but she had hoped it would not find their woodland home. Now the sign of the witch had been tacked to their door.

We know where you are,

it seemed to say

We will not let you rest.

Next morning, she took the padlock from her chest upstairs and fastened it on the little door.

"You shall not leave the house today, my pet." She tried to keep the worry from her tone, worked not to sound too sharp or stern. "For a while, you must wait until I come home to go a'rambling." The day at the fair threatened to play itself out again in her mind, and she shook her head to banish the ugly scene. "And you must not go too far, must never stray toward town."

"But why?" Rampion was accustomed to being on her own in the forest, to tramping when and where she pleased.

"I will tell you by and by, but for now you shall do as I say." Tabby softened, melted by the girl's anguished expression. "Have I ere wanted more than your safety and content?"

The first few days were hard, since no matter how early Tabby rushed home to unlock the tower door, it was never soon enough. "The sun is nearly down," the girl would moan. "I shall have no time at all." Or, "Mother!" she would cry. "You have caged me like a beast!"

But then, for no reason Tabby could find, things settled into an easier pattern. Rampion was sweeter now, always ready with soup and a smile when her mother came home and unlocked the door. Occasionally, she even chose to stay inside rather than take to the woods. "The forest will be there tomorrow," she would say, making Tabby's grateful heart leap. "But you are tired, Mother, and will soon to bed. If we are to sing and sew a bit, we'd best be about it now."

In this way the winter turned to spring, and Rampion asked only a few times when her imprisonment would end. She was easily put off with Tabby's assurances that it would be soon, and indeed, the cross on the tower door began to seem a mere prank, the idle threat of a child. So when, on the first day of a full moon in April, Tabby's dreams came true at last, there was nothing to dilute her joy. "Mother," the girl announced over their mugs of morning porridge, "I must have cut myself on my walk last night. Look how I have spoiled my gown." As soon as she saw the red nightshirt, Tabby's eyes filled.

First blood,

she thought.

My daughter is a woman made for flight.

She embraced Rampion and explained that the blood was a ripeness, not a wound. She showed her how to bind herself, how to wash the cloth and bind again. "And when the blood has stopped," she promised, barely containing her joy, "and the moon is new again, we will take to the woods, you and I." She drew the girl to the window they had fashioned of the useless door, and together they looked out at the forest below. "I will show you a secret there, a secret only we two can share." She pictured the clearing in the woods, imagined them joining the coven's flight. Already, as if it had been days instead of years, she could feel the swift climb, the unstoppable cresting, like a tide in her veins.

The next day, instead of heading for the village, Tabby hurried to the sacred grove. Or rather, to the spot she was convinced she had visited so often before. But when she reached the clearing, she found the ground overgrown with weeds and the altar of stones missing. There were no stray boulders, no tumbled remains at all. It was as if she and her sisters had never met, had never chanted the sacred words or worn the earth smooth with their comings and goings. Could she have forgotten the path? How could her feet have failed to take her the way she knew as well as she knew her name?

For a while she stood, head bent, silent. It was almost like disappearing, losing the last traces of her past this way. But when she looked up again, she was still herself, still the mother of the dearest, fairest child she could imagine. She had not, after all, heard from her sisters in years, had not sought them out or missed them more than a handful of times. Those nights, when the moon swelled and the time of flight neared, she had dreamt of going with them, had felt awash with the old yearning, the call to the sky. But such dreams vanished like dew in the morning, burned away in the fierce love she knew would outlast all others. Nor did she need the sisterhood, she decided now, to pass on the glorious rite, to fly with Rampion at the very next full moon.

As she made her way home, it occurred to Tabby that the coven might simply have grown old. She herself, after all, had been the youngest of them, and the rest (she felt suddenly guilty at the thought) might have died. Part of her grieved her lost friends, while another part trembled with eagerness to share the sweetest secret she knew with Rampion. Little wonder, then, that she failed to notice the second bloody tribute until it met her eye to eye. No harmless cross of twigs this time: it was a goat's head that had been hacked off and nailed to their tower door. The dead eyes were wide, as if stunned by the loss of the body they had been accustomed to steering. The tongue lolled, and a steady red stream still poured from the severed neck. Tabby's first thought was

Poor thing.

Her second was

We must run.

She realized now that the coven had probably left long before, driven out by the same hatred and violent fear that had turned the village against Tabby and her daughter. There was no time to lose, she told Rampion as soon as she had unlocked the door and hurried upstairs; they must escape right away. "I cannot leave you alone again," she said. "I dare not trust your safety, even in our own home."

"And where, pray tell, will we go?" Rampion clearly feared the unknown more than the threats of bullies, which were, after all, quite familiar to her. "They mean nothing, those louts," she told Tabby. "They box with shadows and call themselves men. When I go to town, I point a finger at them and they all fall back, hexed. "

"When you go to town?" Tabby was stunned. And furious.

Rampion blushed. "Only once in a while," she said, "when I have finished picking..." She stopped, shamed by the look on her mother's face.

"I have told you not to walk beyond the woods, have I not?"

"Dear old worrywart!" Rampion smiled fondly at Tabby now. "I ne'er go far. Only to meet my friend for a walk or a game. Or sometimes to peek at the market stalls."

"Friend?" Tabby's hand was on her throat as she sat heavily, suddenly. "What friend, daughter?"

"There, there." The girl touched Tabby's arm as if she were settling a nervous horse. "Do not be peevish. 'Tis only for fun now and then." She hoisted her skirt to show her pretty foot. "Surely you do not mean me to hide the lovely frocks you buy me? Must no one see my finery?" She turned this way and that, jigging steps she could not have taught herself. "There are those in town who fancy my company, Mother, who wait for me to come."

Tabby hid her eyes from her daughter's spinning dance, from the mischief in her smile. She felt little curiosity about her daughter's companions, only the need, savage and certain, to banish them from the girl's life. "You shall not cross me on this, my Rampion. I will make you safe until I find a refuge for us, a new home far from such friends as nail a goat head to your door."

Rampion stopped her dance and bent to put a patient hand on Tabby's knee. "I know no one who would do such a thing, Mother. And a new home will be no refuge for me." She stood straight again, surveyed the dark forest outside the window. "I need to sing and dance. I need to see my friend."

Tabby was certain the girl meant no harm. It seemed to her that Rampion must have snuck into town with the same careless innocence that sometimes made her bring home the wrong mushrooms, the ones that might have killed them both. She was young, after all, and could not know the deadly poisons stored in human hearts. So Tabby struck a bargain, made a promise she hoped would save them both: "I will show you, Rampion my own," she told the girl, "such freedom as you ne'er could dream. Give me until the open moon, and stay inside until the first night she turns her white face on us." It was not so much to ask, surely, of the child she had fed and raised and loved until she felt her heart might burst. "Then, when you have seen what I will share, if you do not want to come away with me, we will stay here." Once her daughter had felt the night sky against her face, Tabby knew, once she had sifted moonlight between her out-stretched fingers, she could never prefer the tame pleasures of flightless companions.

"But when you come home, surely then I can go out?"

"No, pet," Tabby told her. "We must take no chances until I have earned enough to give us a fresh start in a town with kinder folk." She held her daughter's hands, like two trapped birds, between her own. "But I will bring you dainties and games each night. 'Twill make the next day pass so quickly, you will swear the sun has mistaken its course."

To Tabby's surprise, though she sighed a bit and pouted mightily, Rampion agreed. She did not weep or complain of being held captive but settled with a good will beside her mother, taking up her needle. "'Tis but two fortnights," she said, sounding almost cheerful. "I will sew some new sleeves for your gown to keep myself busy. And stir the pot till you come home."

Though she should have been relieved, Tabby slept poorly that night. She dreamt of the goat she had found on the doorânot just its head, but the whole goat, swelled to giant size. Its beard was as big as a tree and its hooves sparked lightning as it ran. It lowered its shaggy head and stormed toward the tower, snorting like a bull. Desperate to save Rampion, who she knew was inside, Tabby began to build a wall across the tower door. Just as she had fashioned the wall around her old garden, she laid stone on top of stone in her dream, building higher and higher. But as she put each stone in place, she saw the goat-bull coming closer, felt the earth shudder under its flashing hooves. Just as she was tapping the last stone into place, she heard a hideous roar and woke from the nightmare, her pallet tumbled off its platform and her nightshirt soaked with sweat.

The dream stayed with her all the next day, so that instead of going into town to work, Tabby went back to the cottage where she had raised Rampion. She was glad the girl was not with her to see what had become of their little home. Marked with an inverted cross like the one that had been tacked on the tower, its shutters burnt away and its door gaping wide, the house had been plundered until it was little more than a pile of rotting timbers. But the round stones in the wall suited Tabby's purpose, and by twos and threes she succeeded at last in hauling several score back to the tower in the woods. The next day, with wet earth and sand for mortar, she managed to seal up the tower door just as she had done in her dream.

It was cruel, backbreaking work, but even though Rampion begged to come down and help, Tabby was too caught up in her dream and her fears to let the girl out. Stone by heavy stone, she covered up the door and barely paid attention when her daughter leaned from the window to tease her. "For all you love me, Mother, this old monster is luckier far than I." She reached down to touch the tongue of one of the gargoyles that perched below the window ledge. "For here he sits in the sweet open air, while I am forced to sniff last night's fire and yesterday's soup."

So intent was Tabby on her labors that she neither smiled at her daughter's antics nor gave a thought to how she herself would enter and leave the place until the moon was full and the power of flight was strong in her again. Only after she had set the last stone and smelled the lentils Rampion put on to cook did she remember the end of her dream, the horror of finding herself on the wrong side of the wall. But this, of course, was different. There was no nightmarish beast storming toward Tabby now, only the foolish shame of having sealed herself away from her daughter and deprived herself of her own bed!