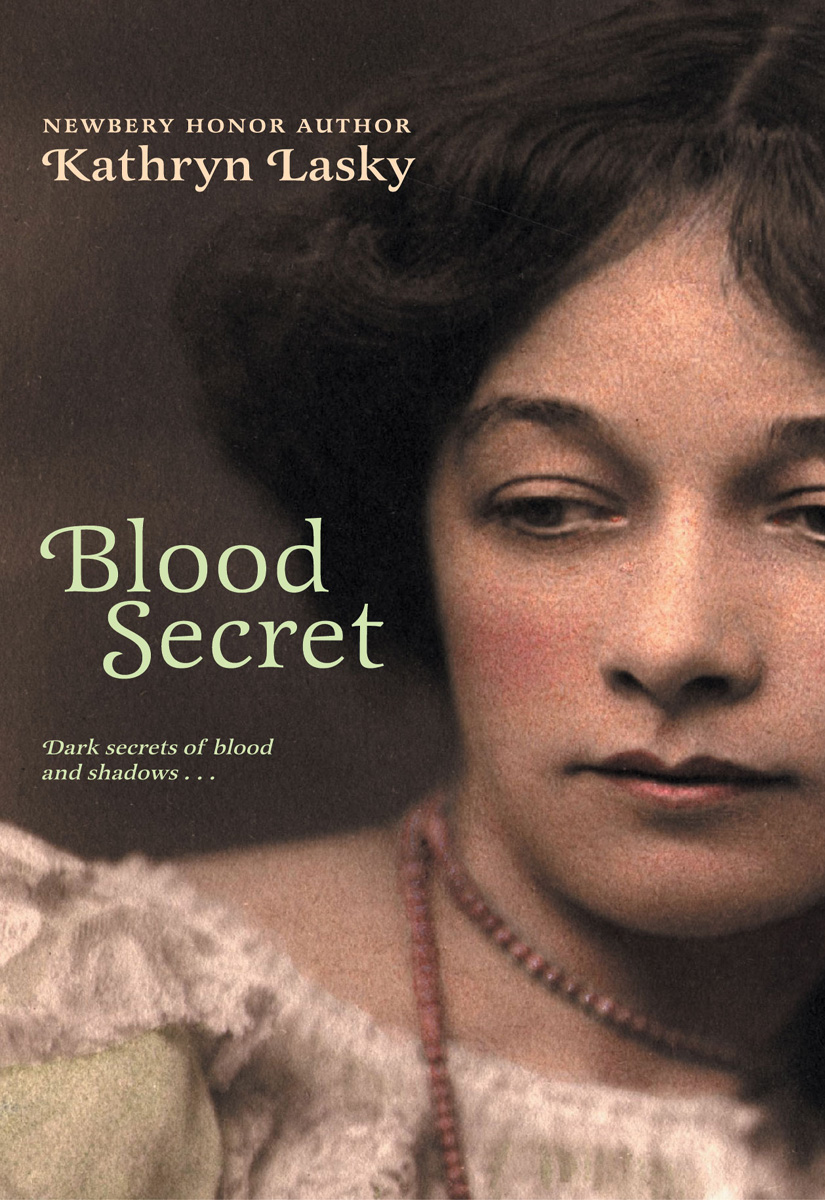

Blood Secret

Authors: Kathryn Lasky

By Kathryn Lasky

In memory of

Meredith Charpentier,

my friend,

my editor,

my navigator

—K.L.

IT WAS THE NOTHINGNESS that woke her up. It was…

THE SECOND TIME she had gone to the Catholic Charities…

A TRUCK HAD JUST driven in ahead of them. It…

JERRY THOUGHT that she and Constanza must have been quite…

JERRY HAD WORN the denim skirt to school the next…

THE CELLAR DOOR creaked as she opened it, and once…

“MAYBE YOUR FRIEND will help you get that sewing machine…

JERRY HELPED CONSTANZA in the cook yard for the rest…

JERRY WAITED UNTIL midnight, when her aunt would be asleep.

JERRY PRESSED HER hands against her eyes as she climbed…

ONCE AGAIN IT WAS Friday night, and once again as…

“WHAT’S THAT IN your hand?” Constanza had just come into…

JERRY LAY IN BED. She had been trying forever to…

JERRY BLINKED AS she walked upstairs. Outside the world had…

IT SNOWED ALL NIGHT, and when she got up the…

“NOW THE LAST THING you ever want to do if…

THE CEMETERY WAS at the crest of a hill, and…

“HELLO!” PADRE HERNANDEZ stepped out of his station wagon and…

IT WAS FRIDAY NIGHT. Jerry was dressing with care. She…

CONSTANZA LUNA STOOD over the sleeping form and watched the…

JERRY IN HER SLEEP felt herself floating on that strange…

WHEN JERRY WOKE up the next morning, she touched the…

“JUST IN TIME, wouldn’t you know it.” Constanza leaned toward…

IT WAS LATE AFTERNOON on Good Friday, and Jerry stood…

JERRY’S HAND SHOOK. She looked down at the doll. Her…

THE NAVAJOS BELIEVE that when the world was created, the…

I

T WAS THE NOTHINGNESS

that woke her up. It was like a hole beside her, as if she were on the edge of it and might fall in. Her mother had been there and then she wasn’t. When they had gone to sleep that night in the tent, they were side by side in the big puffy double sleeping bag, all cozy and curled up together. They fit like spoons against each other. Now the space beside her was blank. She opened her eyes and looked into the darkness. Outside she could hear a few voices. They were camped near the place where the concert would be. A rock concert in a rock stadium. That was funny. She and her mom made jokes about it. They always got to concerts plenty early, days early, so her mom could set up her jewelry stuff and sell it.

Her mom must have had to go pee. She would be back soon. So Jerry waited and waited. Then she

heard her mom’s voice. At last, she thought, and the knots in her stomach dissolved. She got up on her knees and peeked out the little nylon screen square that served as the window. She saw her mom in the big shirt she wore to sleep in and barefoot. Then she saw her crouch down and crawl into the man’s tent, the man named Jim who had sold her the stuff for the pipe she smoked. She watched transfixed. Her mom was naked under that shirt, and as she crawled in Jerry could see her mom’s butt. She put her hand over her mouth. She thought she might cry. She thought she might shout, “Mom—your butt!” She didn’t know what she might say. So she clamped her mouth shut and slammed her hand against it. She crumpled up into the sleeping bag. She wanted to dive right down to the foot of the bag, but then she wouldn’t be able to breathe. Still she felt these sobs swelling up in her throat, so she bit into the puffy quilted squares to stifle the awful wet sounds.

“Jerry, what the hell? You’ve bitten right through this down sleeping bag. Lucky you didn’t gag on the feathers, crazy little girl!” Sure enough, a little thread of down drifted lazily through the air close to the tent floor.

Her mother was back. It was dawn.

“Where’ve you been, Mom?”

“Just out visiting.”

“Jim?”

“Now how’d you guess—you a little peeping tom? Peeping Jerry?”

Jerry didn’t exactly get the joke. She

had

been peeping. “Huh?” Her mother nudged her. She didn’t answer. She didn’t want to say what she had seen—her mom’s naked butt going into that tent. If she’d at least been wearing underpants! “Huh?” Her mom giggled and nudged her again. But Jerry didn’t say anything.

This was the first time Jerry had swallowed words. But the silence was okay. Jerry was five. Over the next few years, it would become easier and easier to swallow the words.

T

HE SECOND TIME

she had gone to the Catholic Charities home, when she was eight, it had been in Colorado, where her mother had disappeared. She was there almost a year. During that time she had thought of her mother every day. She had lit candles. The sisters had always told them at the home that the burning candle was a symbol of heartfelt prayer. Sister Norma had called it a vigil light and a sign of watchful waiting, a true act of devotion, and she had said it was appropriate for Jerry to light such a candle; it was like a light in the window for her mother, for a loved one’s return, for her spiritual return. Jerry’s mother, the nuns told her, could see the flame of the candle she had lit from heaven. You cannot call out to heaven, but the candle silent yet shining shows our love. It was like opening a window

through which a soul could come. It seemed like magic. Jerry imagined a window with the shimmer of a candle reflected and herself holding that candle, waiting in front of the window, waiting for her mother’s soul to hoist itself over the sill and through the window just where the flame shimmered. But the thing was that as soon as her mother stepped out of that window, she would no longer be just a soul. She would be real and she would be safe.

Jerry was patient. She could wait. She could wait a long time if she had to. So she had prayed and lit lots and lots of candles. She had tried to picture her mother dead in a coffin with lilies lying on top of it. She pictured herself kneeling by the coffin. But the problem was, of course, her mother was not for sure dead; she was missing and presumed dead. They had been hunting for her forever in the red rock country. And what help had Jerry been? None whatsoever because, when her mother disappeared, that was when Jerry had stopped speaking completely.

The state troopers had come, search teams, national guards, all to look for the mother of the little girl who was found wandering on the edge of a campground. But she couldn’t speak. Someone at the campsite remembered her mother had said

something about going hiking. The mother had hung out with a lot of potheads and druggies and she didn’t look well. No, not at all. So a search was started. But Jerry couldn’t help them. She knew what her mother had been wearing that day. Her long skirt covered in violets. The ruffled pink blouse, a leather vest, and a big cowboy hat. But she couldn’t tell them. She couldn’t tell them about her mother’s crinkly black hair with the seashells woven in, or the tattoos. She had one on her thigh and one on her belly that said “Hammerhead.” She was going to get one that said “Jerry” and Jerry was going to get one that said “Millie” when they got to the good tattoo place in Arizona. But then her mother had just disappeared.

One day at the Catholic Charities home, Sister Norma had come in and said, “We must think, Jerry, that now for sure your mother is dead. It has been more than a year. I am going to have Monsignor Rafael say a mass for her. We shall buy you a new dress and I think, dear, this will help. And look, the Friends of Catholic Charities have all chipped in and we have made a donation to the Franciscan Mission Association here in Colorado.” She handed Jerry a card. The outside of the card was linen, and

on it inscribed in gold was a drawing of the Virgin sweeping open her cloak as if to enfold a Franciscan brother who held a cross. Inside it said, “To honor God and help spread his kingdom on Earth, a donation has been made to the Franciscan Mission Association on behalf of Mildred Moon, who will share for five years in the prayers and sacrifices of the conventual Franciscan Friars and will be remembered in their masses, including masses said over the tombs of St. Francis in Assisi and of St. Anthony in Padua.”

“Isn’t that lovely, dear? Don’t you want to thank the sisters? Don’t you want to say thank you?” She paused and fixed Jerry with a hard look. “Out loud?”

But Jerry had remained absolutely silent. Sister Norma made it sound very easy. You either were or you weren’t dead. Nothing in between. This card made her mother for sure dead. The Franciscan brothers didn’t pray for the “in betweens,” only for the “for sures.” What if it wasn’t quite for sure? What if her mother wasn’t really dead? What if Millie Moon came walking in and they had already bought the card? Would she have to give the card back? But Jerry liked the idea of praying to her mother in heaven. Her mother would be safe in

heaven. And she, Jerry, got to carry a candle and hold a white lily.

She wasn’t sure when it was that she realized the entire idea of cooking up a dead mother for her was part of Dr. Wright’s notion of therapy. Dr. Wright visited the home once a week. He was sure that once Jerry had “closure,” this would in some mysterious way help her to speak. Stupid! She would have no part of it. In fact, Jerry called Dr. Wright Dr. Wrong. In her mind, of course. She never spoke to Dr. Wrong. Not a word. It was very satisfying watching him trying to draw her out. He tried; they all tried. When the silence first came to her, she didn’t realize she could do this with it, that she could make people almost hungry for her words. The silence was just nice, comforting. There was a coolness that would steal over her, a gray coolness that protected her from the glare out there. Even when they kept badgering her to speak, she could withdraw to that cool place. Silence was like dirt, good dirt. You could dig into it. You could bury stuff in it. She could bury the longing for her mother in this silence. Then one day she discovered that she had actually forgotten the sound of her own voice. She wasn’t even sure if she missed the memory of

her voice. So many years had passed now and with every year she buried the longing deeper, the memory of her voice deeper into the good dirt of the silence.

Jerry felt the nervousness of the woman behind the wheel as they drove down New Mexico Route 25. People were not good at being near stillness and silence. The nuns of course were the worst of all. Nuns were teachers and nurses. Their whole point in life was to teach and heal. They had tried their best with Jerry. She had failed them. She knew what she looked like to them. She looked cut. She looked as if she had a wound that sucked up words and bled silence. But psychologists and social workers weren’t much better. And it was Jerry’s stillness that unnerved Phyllis Wingfield. It was as if Jerry had become part of the car’s upholstery, and she had never seen anything as inanimate as Jerry. So absolutely still. Jerry felt her stealing glances at her from behind those mirror-lens sunglasses she wore. She’s probably wondering if I am real, real for sure alive, like Millie being real for sure dead. Or maybe she thinks I’m just a shadow on the seat.

The San Mateo exit came up. “Restrooms!”

Phyllis Wingfield exclaimed. “I think I’ll stop. Jerry, do you need to stop?” Silence.

They pulled into the rest area’s parking lot. Switching off the ignition, she asked again. “You sure you don’t want to go? This is a pretty clean one, as I remember.” Jerry stared straight ahead. “Well, I’ll be back in a few minutes. I think they have snack machines. I’m having a cookie craving. I’ll pick us up something.” She reached for her wallet and left the briefcase open with Jerry’s file peeking out the top.

Compliant…No organic involvement…

Jerry always read her in-take forms. She had become so adept at it that she could read them upside down if she had to. Under “Antecedent Behavior” there was a short dash. She licked her finger and picked at the next page. Ah, the good old Functional Behavioral Assessment Matrix—comfortably blank except, of course, for the little boxes where they could check the rates of social engagement. The “Not Socially Engaged” box was filled in. There was a recommendation for a neuropsychological evaluation based on a previous clinical report, which was included. There wasn’t time to read the report. The woman

would be coming back any minute. Besides, Jerry knew what it would say.

Selective mutism, complete refusal to speak in social situations, high ability to understand spoken language, to read and to write,

or it might opt to call her silence

“elective mutism”

—that was the clinical term. It made it seem as if being mute was part of an exclusive club.

Jerry continued reading.

Exhibits extreme levels of anxiety when pressed to respond verbally or interact verbally. Otherwise compliant.

That was the single most-used word in any description of Jerry Moon.

Or was it Jeraldine de Luna or was it Jerafina Hammerhead or was it Jerrene Milagros? Her mother, Mildred, had a thing about names—and men, for that matter. She touched the crown of her head and then began picking and rubbing her hair as if she had an itch. But there was no itch. It was just a soothing gesture. She looked up. The woman was heading back. So she flipped to the cover page. There it was. She was Jeraldine de Luna, age fourteen, mother Mildred Milagros de Luna, father Hammerhead. Father deceased. Mother presumed dead. “Whatever!” The word hung as a silent mutter in her head. She stared forward through the car’s windowpane.

Mirror Eyes was smiling broadly. How many times before had Jerry sat in a car and watched a state worker come toward her smiling, someone from some Department of Child Services with mirrored sunglasses? They all seemed to wear them.

“Have a cookie, Jerry?” Phyllis Wingfield peeled back the plastic on the packet and offered her one. Jerry gave a barely perceptible shake of her head.

She looked out the window as the landscape slid by in a blur of muted reds and dusky tans. No trees, just scrub stuff—clumps of snakeweed, needle grass, sagebrush. What grew out here in New Mexico was maybe the least interesting part of the scenery, Jerry thought. It was what had been that was fascinating. There was this strange geometry to the land. The mesas that rose like stacked pancakes must have been carved away by ten thousand winters of scouring blizzards, ten thousand springs of torrential rains. Even from the car Jerry could see a dust storm raging miles away, with whirlwinds scraping across shallow basins and sucking up red dust from one place to drop it in another. As they approached a deep bend in the road, a sign warned of falling rock from the cliffs.

She might see some of the ancient rock carvings.

There were Kokopelli figures all over the place out here. When she had been at the second Catholic Charities home here in New Mexico, there was a rock cliff on the grounds that showed the old flute player that the cave-dweller Indians from seven hundred years ago must have loved for his rowdiness. Kokopelli, with his hunched back and his spindly legs dancing to his own tune as he played his flute in the deep silence of the stone. The nuns took them up there for picnics sometimes. Up close, the red sandstone cliffs were not just red. There were stripes of color—pink, reddish purple. Purplish red, a cool gray. They were really layers of time. In the clear dry air they stood out perfectly—time translated into stone. Neat and organized and yet, as the sign warned, it could crush you. Jerry imagined a boulder breaking off from the cliff and crashing through the roof of the car. She and Mirror Eyes squashed flat under a million years of time—surely, surely dead.

“Jerry, this aunt—she is actually, according to our records, your great-great-aunt, Constanza de Luna—sounds like a lovely woman. She’s a baker. A very good one. Apparently supplies lots of restaurants in the Albuquerque area, as well as some

country clubs. You will have your own room and bathroom, and the high school is walking distance. Now, you’re a freshman, aren’t you?”

No nod this time. “And I understand that except for your reluctance to talk, you are a good student. Indeed, your last school report spoke of your being fluent in reading and writing Spanish as well as English.” She waited; still no response. “That’s wonderful!” Jerry began having the funny feeling in her throat. It happened whenever anyone got hot and bothered about the talking thing. Thank God they were pulling into the drive now.