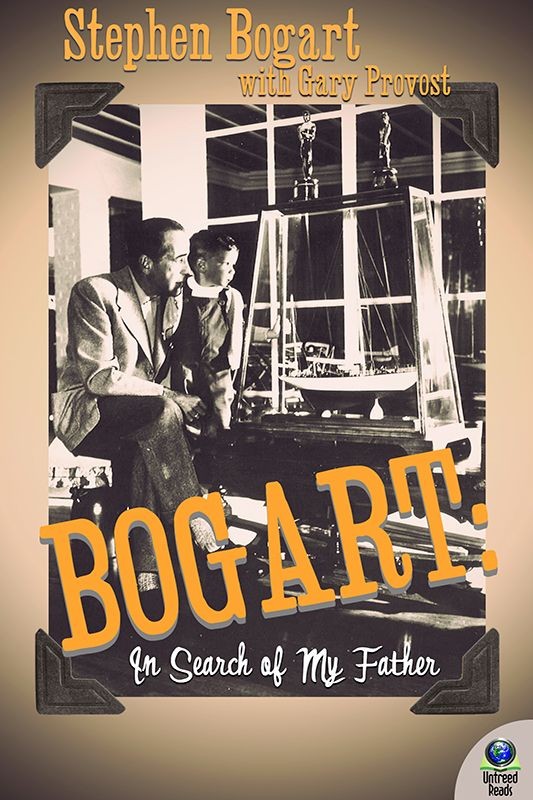

Bogart

BOGART: In Search of My Father

Bogart: In Search of My Father

By Stephen Bogart with Gary Provost

Copyright 2012 by Stephen Bogart

Cover Copyright 2012 by Ginny Glass

and Untreed Reads Publishing

The author is hereby established as the sole holder of the copyright. Either the publisher (Untreed Reads) or author may enforce copyrights to the fullest extent.

Previously published in print, 1995.

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be resold, reproduced or transmitted by any means in any form or given away to other people without specific permission from the author and/or publisher. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person you share it with. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to your ebook retailer and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

BOGART

In Search of My Father

Stephen Humphrey Bogart with Gary Provost

For my father, my three children, Jamie, Richard and Brooke

And in memory of

Gary Provost

1944–1995

Foreword

It is a long road he has travelled since that day on Janu

ary 6, 1949, when Stephen Humphrey Bogart entered the

world. Having firsthand and intimate knowledge of that time,

I would say his first eight years of being Humphrey Bogart’s son were happy years. After that, with the death of his father,

he learned too soon about endings. Growing up as the son of

Humphrey Bogart, with all the curiosity of others that would

bring, and his yearning to somehow emerge with an identity

of his own, was quite a different matter. Having had to cope

with the indescribable pain of loss, the confusion and anger

that accompanies it, the sense of isolation from his two-

parent peers—all throughout his most impressionable, form

ative, and needy years—must have presented obstacles and

miseries beyond comprehension. He did not have the good

fortune of time spent with his father or that most precious

thing—memories—happy memories—to comfort him.

Added to that came the rebirth of Humphrey Bogart;

the discovery of him by new generations elevated Bogie to an

icon, to cult status (a status, incidentally, that now encompasses the world).

But it began while Steve was in his teens.

So it is no surprise that Steve dropped the curtain—not

only to forget the pain of loss—but to try to find a place for

himself.

For many years I have been hoping and praying he

would find a way to come to terms with being his father’s son, would get to know him, and perhaps begin to under

stand the rare qualities that Bogie had as a man—why he rep

resents the kind of character and integrity so hard to find in

today’s world, and why he has become such an important fig

ure to so many.

It cannot have been easy for Steve to face the unearthing

of the past, to face for the first time the reality of his denial,

to face himself. But he has done it. These are his words, his

feelings, his discovery.

Though I cannot say I fully agree with each of his con

clusions, I am happy and proud that he has taken the time

and made this extraordinary effort. I am filled with admira

tion for his accomplishment. And for me, perhaps, what is

most satisfying in these pages is that I think he is now ready to be Humphrey Bogart’s son, with pride, and to pass on all

that he has learned and feels to his children.

I respect him, love him, and am proud to be his mother.

I am thankful that he has opened his heart and mind to what must have been a terribly painful—though I hope enlighten

ing and rewarding—time.

Lauren Bacall

Introduction

When I was a kid I had it all. Just like Bogie and Bacall.

In fact, I had them, too. Humphrey Bogart and Lauren

Bacall. They were my parents.

In the early 1950s we lived in a beautiful fourteen-room

house at 232 South Mapleton Drive in Holmby Hills, which is a pricey little slice of real estate between Bel Air and Beverly

Hills. It was a great house, two stories of whitewashed brick,

hidden from the street by hedges and trees. At the entrance

to the driveway there was a two-foot brick wall. On it my fa

ther had hung a sign: DANGER, CHILDREN AT PLAY.

For years the house was only partially furnished. The liv

ing room, especially, always looked incomplete, as if the

family had just moved in. I’m not sure why, exactly. I think it

was because my mother had promised Dad that if he came

up with the money for the house she would furnish it slowly.

Dad really wasn’t interested in having a big house. He was

the kind of guy who could be happy with two rooms, as long

as one of them had a bar in it.

We also had a tennis court, a four-car garage, a lanai

with wrought-iron tables and chairs, and an expansive lawn

where my little sister, Leslie, and I used to do somersaults

and play on the jungle gym that my father had bought us. After we moved in, Mother installed a swimming pool, where even today you can see the footprints that Leslie and I left in

the concrete.

Along with the two movie stars and the two kids, there

were three dogs named Harvey, Baby, and George. To serve

us all there was a maid, a butler, a gardener, and a cook.

Just as well. My mother was no cook, and my father was

no handyman.

I must have thought that everybody lived this way. Sybil

Christopher, who was Mrs. Richard Burton when I was a kid,

says she took me to see

Hans Christian Andersen

when I was six

years old and she remembers that when we walked up to the

balcony of one of the huge old opulent movie theaters in Los

Angeles, I asked her, “Whose house is this?”

The early fifties were an idyllic time and I have many

fond memories of Mapleton Drive. But when I think of the

house, I think, too, of my greatest regret, the fact that I had

so little time there with my father. It is a regret made more

poignant in recent years by the fact that I ignored his mem

ory for most of my life. I resented Humphrey Bogart for rea

sons I only now understand, and for almost four decades I avoided learning about him, talking about him, and thinking

about him. It was only with the marriage to my second wife,

Barbara, in 1984, and with the birth of our two children, Richard and Brooke, that I began to pull from my shoulder

a chip the size of Idaho that had been there since the death

of my dad when I was eight.

I think in the early days of our marriage Barbara was

shocked when she began to realize that I knew less about my

father than many of his fans. Here I was, telling my new wife

that the most important thing to me was family, and I

couldn’t even score well on a Bogie trivia test at the back of

a magazine.

It’s not as though nobody had ever urged me to find out about my father. Mother had been doing it for years. But you

know how it is when your mother tells you that you should do

something. It’s practically a guarantee that you won’t do it.

I might have gone on forever, fleeing my father’s ghost

at every turn. But Barbara wouldn’t let me. She understood

how I was feeling about it, understood certainly better than I

did, and she didn’t try to change my feelings. She simply

showed me how important it was to know who my father was

if I really wanted to understand who I was. She let me see

that just because I didn’t want to glorify my father, that didn’t

mean I had to ignore him.

“Find out about your father,” she said. “Talk to your

mother. Talk to his friends. I want our children to know

about their grandfather.”

And so I began to read about my father. I delved, reluc

tantly at first, back into my memories of him. And I visited

people who knew him. I talked to people he did business

with, like Sam Jaffe, his agent, and Jess Morgan, one of his

business managers. I talked to people who had played in

movies with him, like Katharine Hepburn and Rod Steiger. I

talked to some of his writer friends, like Alistair Cooke and

Art Buchwald. And I talked to family friends, like Carolyn

Morris, and people who had known him briefly, like Domi

nick Dunne, and friends who had written about him, like

Joe Hyams.

Perhaps if I were not Humphrey Bogart’s son, but just

some guy writing about Bogie, I would have spent more time

with Lauren Bacall than with anyone else. But she’s my

mother. I already know her opinions on the subject. She

helped me a great deal, but ultimately she wanted me to do

this without having her as a crutch. But I think Mom is

pleased. My father has become a character of folklore, and

there are so many contradictory stories about him, that I

needed to hear what a lot more people other than my

mother had to say. Also, Bogart lived more than three-

quarters of his life before he met Bacall. So if there are mis

takes in this book, and I’m sure there are, don’t blame Mom.

And don’t blame the other people I spoke to. It is the

nature of a legend like Bogie that the stories about him get

embellished, relocated, even folded in with other stories. The

precise truth is always elusive. But there are many people

who took the time to tell me the truth about my father as they knew it, and I want to thank them:

Dominick Dunne, Carolyn Morris, Alistair Cooke,

Adolph Green, Rod Steiger, Katharine Hepburn, Phil Gersh,

Jess Morgan, Sam Jaffe, George Axelrod, Art Buchwald, Joe

Hyams, Sybil (Burton) Christopher, Gloria Stuart, Julius Ep

stein, Bruce Davison, William Wellman, Jr., Joe Hayes, my sis

ter, Leslie Bogart, and, of course, my mother.

I want to thank, too, the many celebrities and writers

whose written words have led me to greater knowledge of my

father. Special thanks go to Joe Hyams for

Bogie

and Nate

Benchley for

Humphrey Bogart.

Thanks go also to Katharine

Hepburn for

The Making of

The

African Queen, Janet Leigh

for

There Really Was A Hollywood,

Richard Schickel for

Legends:

Humphrey Bogart,

Melvyn Bragg and Sally Burton for

Richard Burton: A Life, 1925–1984,

John Huston for

An Open Book,

Gerold Frank for

Judy,

Bob Thomas for

Golden Boy,

Charles

Higham for

Audrey: The Life of Audrey Hepburn,

Vera

Thompson for

Bogie and Me,

Edward G. Robinson for

All My Yesterdays,

and Lawrence J. Quirk for

The Passionate Life of Bette Davis.