Book of Fire (22 page)

Someone, Rinck or the printer Schott, was lying. Perhaps each of them was, for there was money in it for both of them. Rinck told Wolsey of a ceremonial oath in front of the consuls at Frankfurt. Here, ‘using my papal and imperial mandates’, he compelled Schott to swear how many copies of

Rede me

and

Brief Dialogue

he had printed. ‘He confessed on oath,’ Rinck claimed, ‘that he had only printed a thousand books of six sheets and a thousand of nine sheets, and this at the order of Roy and Hutchins.’

But Hutchins–Tyndale had not ordered these two little works, which he loathed as heartily as he despised Roye. The scene is pure fiction. It is conceivable that Schott misled Rinck, though barely so, since the printer will have not have known the deep interest that Rinck’s well-heeled patrons in England were taking in Tyndale. Rinck had every reason to involve Tyndale, by fraud if necessary; it was what his paymaster, Wolsey, wished to hear. And by inventing a scene in which the printer confirmed on oath the numbers of sheets he had printed, Rinck was able to show how brilliantly he had scotched their distribution. ‘I have therefore bought almost the whole,’ he wrote in a purr of self-satisfaction, ‘and have them in my house in Cologne.’ That left one last detail – to get a price from Wolsey. ‘Will your grace inform me,’ Rinck concluded, ‘what you wish to do with the books thus purchased?’

Rinck sent Wolsey a bill for £63 4s for his services. It was still

unpaid the following spring. Wolsey had other things on his mind. The divorce of Henry from Catherine had seemed to be set fair a few months before, but now it was haunting him more than ever. The hopes of the king, and of Anne Boleyn, were constantly being raised and then dashed, a cycle that infuriated the hot-tempered Henry.

Matters had seemed much more promising in the spring. The envoys sent to Rome – Stephen Gardiner, Wolsey’s secretary, and Edward Foxe, an expert in canon law – had been granted an audience with the pope. Clement said that he had heard that the king’s wish for an annulment was motivated by his personal lust and ‘vain affection and undue love’ for an unworthy lady. Gardiner replied that Anne was ‘animated by the noblest sentiments’, that ‘all England do homage to her virtues’, and that Queen Catherine suffered from ‘certain diseases’ which meant that Henry could not treat her as his wife. This was nonsense. The queen was too old to have any real hope of producing a male heir, but she was otherwise healthy enough, and the English had a warmth and respect for her that sharpened the public contempt for Anne. She was called ‘Nan Bullen the naughty paikie’, or ‘the King’s whore’, which meant the same.

Gardiner’s counterattack, and his bullying of the pope, were nonetheless effective. The pope agreed to send Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio to try the case for an annulment with Wolsey in England. Campeggio had first visited England a decade before, to whip up support for a crusade against the Turks. Henry had later made him bishop of Salisbury, a position he combined with the archbishopric of Bologna and residence in Rome. He was the preferred candidate to hear the case and Henry greeted the news with ‘marvellous demonstrations of joy’. Wolsey was less optimistic. ‘I would obtain the decretal bull with my own blood if I could,’ he said.

The harvest in 1528 was poor, the weather foul and mortality

high with bouts of sweating sickness. This plague killed most of its victims on the first day, sometimes within an hour or so of the first appearance of the symptoms, a ‘profuse sweat which devours the frame’ accompanied by a foul smell with a ‘great and strong savore’ and thirst and delirium. Thomas More believed the hunger and sickness to be punishment from God for the import of Tyndale’s heresy into the realm through ‘the receypte of these pestylente bokes’. Henry ascribed it to the Almighty’s vengeance for his efforts to divorce Catherine. His guilty conscience and hypochondria kept him in her company through most of May and June, as he moved his court from house to house ahead of the plague.

In mid-June, one of Anne’s waiting ladies caught the sickness. Anne was sent home to her father’s castle at Hever. ‘I implore you, my entirely beloved, to have no fear at all,’ Henry wrote to her from a safe distance. ‘Wheresover I may be, I am yours.’ Wolsey took advantage of Anne’s absence, and Henry’s renewed companionship with the queen, to urge him to drop his annulment suit. The French ambassador witnessed the scene when Henry opened the cardinal’s letter. ‘The king used terrible words, saying he would have given a thousand Wolseys for one Anne Boleyn,’ he reported. ‘No other than God shall take her from me …’

God came close to doing so. Anne caught the sweating sickness in late June, on the same day that her brother-in-law died of it. Henry sent Dr William Butts, a royal physician, post-haste to Hever. Anne had only a mild case of the sickness and she was soon fully recovered.

Butts, as it chanced, was an evangelical and he funnelled her grateful support and patronage to his fellow believers. Butts was a graduate of Gonville Hall at Cambridge, a centre of the ‘evangelycall fraternyte’, and so notoriously radical that the reactionary Bishop Nix of Norwich fumed: ‘I heare not clerk that hath come out lately of that college but savoureth of the frying pan, though

he speak never so holily.’ Anne was generous, and the contact with Butts enabled her to pass on money to support poor students with Lutheran sympathies. One fortunate scholar was given the handsome sum of £40 to study abroad for a year; another recalled years later that she had ‘employed her bountiful benevolence upon sundry students, that were placed at Cambridge’.

The love of the king’s life was increasingly sympathetic to Tyndale and his sort, while Henry himself was maddened by the pope. Cardinal Campeggio did not leave Rome until the end of July 1528. He did not arrive in London until 8 October, travelling at a snail’s pace. The pope had instructed him to try to ‘restore the mutual affection between the king and queen’, and if this proved impossible to ‘protract the matter for as long as possible’. Campeggio used his painful bouts of gout as an excuse for his tardiness. The following day he met with Wolsey. Rinck’s letter from Cologne arrived at this time, together with pleas from Hackett asking for evidence linking Herman with sedition and treason, without which the Antwerp court would not proceed with the prosecution. But the Tyndale affair played second fiddle to Wolsey’s discussions with Campeggio on Henry’s ‘great matter’.

Campeggio suggested that the best solution was for Henry to become reconciled with Catherine. It was no surprise that, as he reported back to the pope, he had ‘no more success in persuading the Cardinal than if I had spoken to a rock’. He spoke with the king on 22 October. He made the mistake of showing Henry a decretal bull, which the pope had secretly signed for use if the marriage could be honourably annulled – if, for example, Catherine could be persuaded to enter a nunnery. Though Campeggio told the king that it was ‘not to be used, but kept secret’, Henry naturally assumed that he would have it. Nothing would satisfy the king short of papal confirmation that his marriage was invalid. ‘If an angel was to descend from heaven,’ Campeggio thought, ‘he would not be able to persuade him to the contrary.’

Catherine was as uncompromising as the king when she met Campeggio and Wolsey. She swore that she had never consummated her first marriage to the king’s dead brother, and said that she ‘intended to live and die in the estate of matrimony to which God had called her’.

O

n 2 October 1528, Tyndale published

The Obedience of a Christian Man

. It was also paperback size, closely printed in Gothic black letter type. It laid out in thrusting prose the two great principles of the English Reformation: the supremacy of the scriptures over the Church, and of the king over the State.

Tyndale made the first point in one of the marginal notes that peppered the book like newspaper crossheads. ‘Christ is all to a Christian man’, he wrote. Rome’s claims were dismissed as pithily: ‘The pope’s dogma is bloody.’ The monarch, a point Henry VIII did not overlook, was invested with absolute authority: ‘A king is a great benefit be he never so evil.’

A false colophon claimed that

Obedience

, like

Mammon

, was printed ‘at Marlborow in Hesse … by me Hans Luft’. The ten copies that survive suggest that Tyndale changed printers to work with Martin Lempereur in Antwerp. Lempereur was a Frenchman who settled in Antwerp in 1525, where his name was translated as De Keysere, or Caesar. He printed humanist works, school texts and historical writings in his legitimate business. For his heretical books, however, he falsified the colophons to show that they were

printed by ‘Iacobum Mazochium’ at Tiguri or Zurich, ‘at Argentine by me Francis Foxe’, or ‘at Straszburg by Balthassar Beckent’. For

Obedience,

Lempereur continued with van Hoochstraten’s Luft identifier.

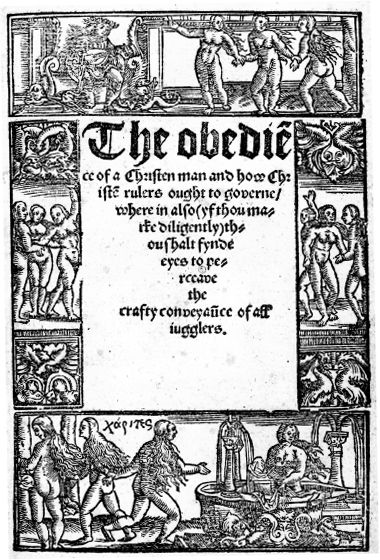

The title page of Tyndale’s

Obedience

, which he had printed in October 1528. The border was a job lot of woodcuts already used in two books printed in Cologne. The content, however, was a fresh and brilliant argument in favour of the authority of kings over popes. More called it ‘a holy boke of disobedyence’. The first copies were smuggled into England within a few weeks. It was banned, and soon joined the New Testament in the flames at St Paul’s Cross.

(British Library)

Where Tyndale wrote it is not certain. He knew that he was being hunted, and he may have been especially vigilant, for he referred with feeling in the book to the spies that the Church employed in every parish, ‘in every great man’s house and in every tavern and ale house. And through confession know they all secrets, so that no man may open his mouth to rebuke whatsoever they do, but that he shall shortly be made a heretic.’ He was able to preserve the secret of his own whereabouts, despite the searching made by the ambassador, Hackett, by Style, the leader of the English expatriates, and by at least three commissioned agents, West, Flegh and Rinck.

Obedience

was relatively free of printing errors, a sign that an English-speaker had watched it into the page, and Tyndale was most probably in Antwerp to oversee its printing in September and October 1528. While it was coming off the presses, Rinck and West were chasing red herrings in Cologne and among the book-stalls at the autumn Frankfurt Fair. But Style and Hackett were in Antwerp and will have visited the streets around the Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekathedraal, where the print shops were. Neither man knew Tyndale, however, and whatever description they had been given from London was four years out of date by now.

Tyndale began his preface by acknowledging that the reader as well as the writer of the book was putting his life in danger. ‘Let it not make thee despair, neither yet discourage thee, O reader,’ he wrote, ‘that it is forbidden thee in pain of life and goods, or that it is made breaking of the king’s peace, or treason unto his highness, to read the word of thy soul’s health …’ His prose has a melody that pleads to be read aloud, as indeed it was, of course, in meetings of fearful men and women – with an eye on the window, and an ear

for the footfall of a bishop’s officer – who gained strength from that salving phrase ‘the word of thy soul’s health’ and from the call to courage that followed it. ‘But much rather be bold in the Lord, and comfort thy soul,’ Tyndale went on. ‘Christ is with us until the world’s end. Let his little flock be bold therefore, for if God be on our side, what matter maketh it who be against us, be they bishops, cardinals, popes or whatsoever names they will?’

He wrote of endurance with the striding rhythm and resonance of his New Testament. ‘If God provide riches, the way thereto is poverty,’ he warned. ‘Whom he loveth, he chasteneth; whom he exalteth, he casteth down; whom he saveth, he damneth first. He bringeth no man to heaven, except he send him to hell first.’ The notion of God working with the existing Church was dismissed with the vivid disdain of a simple metaphor. ‘He is no patcher. He cannot build on another man’s foundation,’ he wrote of God. ‘We are called, not to dispute as the pope’s disciples do, but to die with Christ, that we may live with him, and to suffer with him, that we may reign with him.’

This was English that could growl, or slash and burn, or float as lightly as dandelion down, steeped in a liveliness that had died in Latin. It was a language able to meet every demand made of it. Tyndale said that it was nonsense to pretend that English was ‘too rude’ to express the scriptures. ‘Has not God made the English tongue as well as others?’ he asked with pride and affection. Greek and Hebrew, he said, ‘go far more easily into English than Latin’. The Church allowed people to read of Robin Hood, or Hercules, or ‘a thousand other ribald or filthy tales’ in English. It was ‘only the scripture that is forbidden’, and it was clearer than the sun that this forbiddal ‘is not for love of your souls, which they care for as the fox doth for the geese’.

The Vulgate was itself a translation, he pointed out, made from the Greek and Hebrew into Latin by St Jerome. Tyndale said that he had read as a child how King Athelstan had ‘caused the Holy

Scripture to be translated into the tongue that then was in England’, and how the prelates then had encouraged him to do so. Now, he said, the clergy prayed, christened, blessed and gave absolution in Latin. ‘Only curse they in the English tongue,’ he said, and he made another rare reference to his childhood, recalling how a man who had an ox or cow stolen on the Welsh borders would ask the curate to pronounce a solemn curse on the thief.