Book of Fire (43 page)

A copy survives in the British Museum, the earliest pirate copy known to exist. It is a well-printed enough little volume, without notes or glosses, and Joye’s work was competent. He made few changes, though, when he did, he sometimes guessed wrong. Thus, in a passage in Matthew 6, where Tyndale’s original read ‘else he will

lene

the one and despise the other’, Joye substituted ‘else he will

love

the one’. Tyndale himself rectified his error in the 1534 edition: ‘he will

lean to

the one’.

In one important respect, however, Joye wilfully changed Tyndale’s meaning. Tyndale had claimed, in his controversy with More, that ‘the souls of the dead lie and sleep till Doomesday’. Joye, in common with most others, believed that the soul passed on to a higher life at death. He had several arguments over this with Tyndale. ‘As we walked together in the field’, Joye wrote – an interesting detail which, together with Vaughan’s similar meetings, suggests that Tyndale was careful to set up his meetings in the open air rather than at a particular address – Tyndale ridiculed his ideas by ‘filliping them forth between his finger and his thumb after his wonted disdainful manner’. Joye took his revenge in print. Where Tyndale used ‘resurrection’, Joye substituted the phrase ‘life after this’, except where the passage clearly concerned the resurrection of the body. Thus, in Matthew 22, Tyndale wrote: ‘in the

resurrection

they neither marry nor are given in marriage … as touching the

resurrection

of the dead, have ye not read?’. Joye altered these references: ‘

in the life after this

they neither marry … as touching

the life of them that be dead

…’.

The souls of the dead were not ‘already in the full glory that Christ is in’, Tyndale wrote; Christ had said that ‘the time shall come’ in which all that are in the grave shall hear his voice, but

that time of resurrection had not yet arrived. Joye was premature to claim that those who have done good shall at the moment of death ‘come into the very life’; and this flaw was so great that Tyndale would not accept it ‘though the whole world should be given me for my labour’.

This preoccupation with the grave was timely. Tyndale’s enemies would see to it that he did not have one.

T

yndale had been living in the English House at Antwerp since the middle of 1534. It is the first definite address that we have for him since he left Little Sodbury Manor and Humphrey Monmouth’s London house a decade earlier.

The English House was a mansion that the city magistrates had given to the English merchants sixty years before to encourage trade with England. It served much the same purpose as the Steelyard did for the Hanseatic traders in London. It stood in its own alleyway in a block of streets, now bounded by the restaurants and lace shops of Zirkstraat and Oude Beurs, a few hundred yards north of the city’s Grote Markt, the great market square, and the cathedral. A similar building survives today close by, a tall and gabled house built for the guild of archers. Known as Den Spieghel, The Mirror, it also stands discreetly at the end of a cobbled alley. It was well known to Thomas More, for it had been bought in 1506 by his friend Pieter Guilles – ‘a very fine person,’ More wrote of him, ‘and an excellent scholar’ – and More had described meeting Guilles and the adventurer Raphael Hythlodaye in the opening scene of

Utopia

.

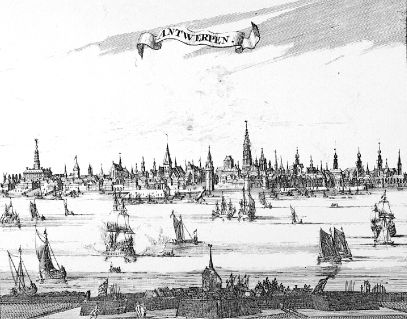

The waterfront on the Scheldt was three streets away. Its

skyline was webbed by the masts and rigging of bluff-bowed merchantmen with heavy leeboards and lighter galliots, which mingled with the spires, towers and belfries of a score of chapels, churches and monasteries. The English Quay, tucked downriver from the cannon and towers of the Steen Castle, handled most of the wool trade across the Narrow Sea, with other specialist quays and warehouses for wines, grain and spices. The world’s first stock exchange opened in the city in 1531, in an elaborate

pinnacled building in the Flamboyant Gothic style close to Tyndale’s new home.

A view of Antwerp and its waterfront across the Scheldt river. It was the greatest commercial city in northern Europe in the 1520s and 1530s, a thriving port known simply as ‘the Metropolis’. Though nominally a Catholic city, its printers and shipowners were willing to produce illegal Bibles and run them across the Narrow Sea to the Thames and the creeks of Suffolk and Essex. The English House, the only definite address we have for Tyndale in all his years on the Continent, lay in a narrow street close to the Cathedral, whose high spire is at the centre of this view.

(Mary Evans Picture Library)

He was close, too, to the soaring beauty of the Cathedral of Our Lady. Its graceful north spire, ninety-eight years in the building, had recently been completed; at more than 450 feet it acted as a landmark for shipping and as a symbol of Catholic extravagance to puritan evangelicals. A fire a year before Tyndale took up residence in the English House had burnt out the roofs of the nave, the transept and the south tower. The wooden trusses above the nave had not yet been vaulted over with stone, and the timbers fell in flames into the church, destroying some sixty altars and their retables, a measure of the rich ornamentation that Tyndale and the reformers so disliked. The English merchants had their own side-chapel, presented to them in recognition of their importance to the prosperity of Flanders, with an altar named for St Anthony, and a stained glass window dedicated to Henry VII and bearing a red rose in deference to his Lancastrian forebears.

The English House was run by Thomas Poyntz, a sympathetic and, as events proved, courageous man who was a relation of Lady Walsh of Little Sodbury. Membership of the House was much valued. The citizens of Antwerp enjoyed several legal privileges, including freedom from arbitrary arrest and detention without trial, and these were extended to the English merchants. As a resident of the House, Tyndale could only be arrested within the confines of the building for a grave crime for which evidence of guilt already existed. Richard Herman, the merchant who had been arrested in 1528 on charges of helping Tyndale, had petitioned Queen Anne to help him regain his membership two months or so before Tyndale’s arrival in the House. Anne wrote to Cromwell in May 1534 to say that Herman had been ‘expelled from his freedom and fellowship of and in the English house’ for his ‘help in the setting forth of the New Testament in English’. She urged Cromwell to see that ‘this good and honest

merchant’ should be ‘restored to his pristine freedom, liberty and fellowship’. It may be that the special vellum copy of the revised New Testament that was sent to Anne from Antwerp, inscribed

Anna Regina Angliae

, was a gift of thanks for her intervention.

Details of Tyndale’s routine at this time were passed on to Foxe, probably by Poyntz. Tyndale was ‘very frugal and spare of body’. He kept two days a week for what he called his ‘pastime’. On Mondays, he visited the Englishmen and women who had fled to Antwerp, whom he ‘did very liberally comfort and relieve’, providing for the sick and diseased. On Saturdays, he walked round the town, looking into ‘every corner and hole’ for the old and weak, and families overburdened by children, whom he ‘also plentifully relieved’. The English merchants at Antwerp had begun giving him a stipend, so that he had a secure income for the first time since leaving Little Sodbury; he gave ‘the most part’ of this to the poor. On Sundays, he would go to an English merchant’s rooms, and ‘read some one parcel of scripture’ to those who gathered there. He also read for an hour or so after dinner, ‘so fruitfully, sweetly, and gently’ that he brought ‘heavenly comfort’ to his audience.

The rest of the week was given ‘wholly to his book’. He saw the revised New Testament through the press in November 1534, and started work on a third edition. He was also close to completing the Old Testament historical books from Joshua to II Chronicles. The three short books of Ezra, Nehemiah and Esther were then to follow before he tackled Job – whose suffering innocence Tyndale shared, if not his patience – and the mass poetry of the one hundred and fifty Psalms.

Tyndale had recently turned forty: he had every reason to look forward to completing his life’s work, in the comfortable and sympathetic surroundings of the English House in Antwerp. Or, indeed, in England. The two men most in the ascendancy,

Cromwell and Cranmer, were favourable to reform. The first printed French Bible had recently been produced by the scholar Jacques Lefèvre d’Etaples, to join the translations already made in German and Italian. An English Bible was within a whisker of gaining official approval. Convocation, meeting on 10 December 1534, petitioned the king ‘that the sacred Scriptures should be translated into the English tongue by certain honest and learned men for that purpose by his Majesty, and should be delivered to the people according to their learning’. No royal command was issued, but Miles Coverdale began to integrate Tyndale’s existing translations into a complete Bible, dedicated to Henry VIII. Coverdale was a Cambridge reformer and renegade Augustinian friar who had fled abroad in 1528; Foxe says he joined Tyndale in Hamburg in 1529, staying with him in the house of the widow Margaret von Emerson, and ‘helped him in the translating of the whole five books of Moses’. Coverdale based his work on Tyndale where he could; the missing books of the Old Testament he translated from the German versions of Luther and Zwingli, with guidance from the Vulgate and the translation from the original Hebrew into Latin completed by the Dominican scholar Pagnini in 1518.

Tyndale’s great enemy was still writing furiously from Chelsea – warning of the ‘corrupt cankar’ of heretics, and advising his readers not to ‘so mych as byd theym good spede or good morrow whan that we mete them’ – but More was himself now in peril as the king’s anger with papal loyalists grew apace.

The pope had already denounced the Boleyn marriage as invalid. In March 1534, after seven years of vacillation, Clement finally pronounced judgement in Henry’s annulment suit. He declared that the marriage of Henry and Catherine ‘always hath and doth still stand firm and canonical, and the issue proceeding standeth lawful and legitimate’. Henry was required to resume

living with Catherine, and to treat her ‘as becometh a loving husband and his kingly honour so to do’. For good measure, Henry was ordered to pay the legal costs of the suit.

Catherine had been redubbed the ‘Princess Dowager’, as the widow of Henry’s brother Arthur, a title she refused to accept, maintaining that she was still the rightful queen; her household was removed from her, and she was sent to the damp and ancient palace of the bishop of Lincoln on the edge of the fens at Buckden in Huntingdon. Her daughter was downgraded from ‘Princess’ to ‘Lady’ Mary, as befitted her new status as a bastard, and she was separated from her mother. All this the pope required Henry to throw into reverse; the king was bidden to abandon his new wife and daughter Elizabeth, at a time when Anne was pregnant with a child who transpired in July to be stillborn, but who in March was expected to be the long-awaited boy.

The king was obliged to protect himself and the succession. The pope himself was denounced as a ‘bastard, simoniac and heretic’. Cromwell saw More as the most prominent defender of the papacy and the old queen, and moved against him, trying to link him with Elizabeth Barton. This young woman – known as the ‘holy maid of Kent’ to the many who believed in her, and the ‘mad nun’ to those who did not – had become famous for the prophecies she made while swooning in mystic fits. She saw Anne Boleyn being devoured by dogs, and Henry recrucifying Christ with his adultery, and predicted that their marriage would bring disaster and lose the king his throne. More had visited the nun shortly before Cromwell had her arrested and brought before the Star Chamber accused of high treason. It was her ‘damnable and diabolical instrumentality’ that had turned the pope against the king, so claimed Thomas Audley, More’s replacement as lord chancellor. Barton herself was then taken with her retinue of priests from the Tower to St Paul’s Cross, where she stood on a scaffold and publicly confessed that her prophecies were fraudulent. An Act of

Attainder was passed by parliament confirming her treason, and naming as accomplices More and John Fisher, the hardline bishop of Rochester and Tyndale’s old foe.

More assured Cromwell that, in his talks with the nun, ‘we talked no worde of the Kinges Grace or anye great personage ells’. He sidestepped this issue neatly enough, but Cromwell was concocting another in parliament that he could not evade without betraying his faith. An Act of Succession was introduced, pronouncing the marriage of Henry and Catherine to be ‘void and annulled’; it implicitly dismissed papal jurisdiction and authority by adding that no power had the right to uphold such a marriage. Anyone who said or wrote anything ‘to the prejudice, slander or derogation of the lawful matrimony’ of Henry and Anne would be guilty of high treason. The new Act required every English man and woman who was called upon to swear an oath ‘that they shall truly, firmly, constantly, without fraud or guile, observe, fulfil, maintain, defend and keep the whole effect and contents of this Act’.