Book of Fire (46 page)

There the matter has rested. But the case against Stokesley is thin indeed. Antwerp was London’s prime trading partner and the leading commercial city of northern Europe. The bishop of London had many servants. It would have been strange had some of them not had business in Antwerp. Docwraye was later to become the first master of the Stationers’ Company. He was known to have visited Antwerp printers, not to ask after Tyndale, but to place orders for the London diocese for the devotional books that Stokesley was importing from Antwerp. As part of his campaign against heretical books, Stokesley was actively promoting orthodox texts on his own account; an example was a fiery attack on Luther by the Catholic theologican and debater Johann Eck. Vaughan mentioned Docwraye’s visit in innocent terms in a letter to Cromwell on 3 August 1533. ‘The bishop of London has had a servant in Antwerp this fortnight,’ he said. ‘If you send for Henry Pepwall, a stationer in Paul’s Churchyard, who was often with him, he will tell you his business.’ Vaughan was much more concerned with the threat posed by Peto. ‘A friar comes from

England every week to Peto,’ he wrote, adding that ‘More has often sent books to Peto in Antwerp.’ Vaughan was worried enough to arrange for a colleague, George Cole, to ‘advertise you [Cromwell] in my absence whatever he learns of Peto and his accomplices’. Peto, he added, ‘is much helped out of London with money’.

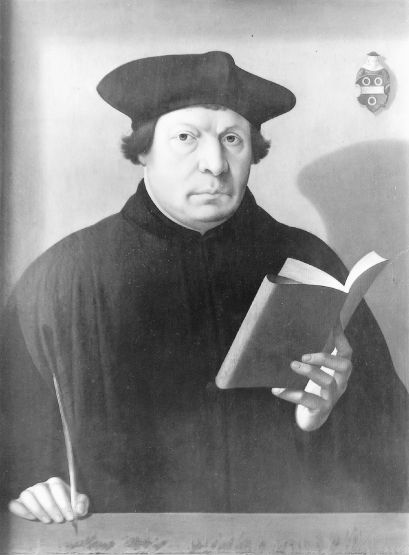

John Stokesley, friend of Thomas More and a heretic-hunting bishop of London from 1530. He was a careerist, however, who ever sought to ‘invent some colorable device’ to promote himself. It is unlikely that he would have risked the wrath of Cromwell and the king by paying to have Tyndale betrayed.

(National Portrait Gallery)

As for Stokesley’s dying boast, not only was the figure of thirty-one burnt heretics absurd – he can be linked to five or six at most – but Foxe would most certainly have mentioned it if any rumour then current had linked the bishop to Tyndale’s death. Why, too, if he was bragging, did he not crow that Tyndale was among them? Stokesley had, in fact, lamented his own ‘helplessness’ and ‘cowardice’ in the ‘face of advancing heresy’, and had declared that he wished that he had had the same ‘courage’ to resist heretics that Bishop Fisher had displayed. He would hardly have berated himself so if he had engineered the death of the great heretic.

Stokesley was a difficult man, loud, bad-tempered, opinionated and tactless, quite the reverse of whoever so smoothly and secretly spun the web that caught Tyndale. Nothing suggests that Stokesley had any singular obsession with Tyndale, or that he was capable of finding a Harry Phillips and using him to such effect.

Stokesley was fifty-five in 1535, fifteen years older than Tyndale. He had missed teaching young Tyndale at Oxford only because he had become involved in an outbreak of academic infighting. Stokesley had been elected an Oxford fellow in 1495, and two years later became an usher at Magdalen School, which the boy Tyndale was soon to attend. After a spell at Magdalen Hall, Tyndale’s old college, Stokesley was appointed praelector in philosophy and vice-president of Magdalen College in 1505. His appointment was a catalyst for bitter academic politicking at the college, which split into two hostile camps. Stokesley was accused of every ill that rival scholars could imagine. Heresy, theft, perjury

and adultery were deemed insufficient, and witchcraft, neglect of duties and christening a cat were added to an official complaint. The bishop of Winchester, alarmed at the state of the college, was obliged to intervene. Stokesley denied all the charges against him on oath in January 1507. No witness came forward against him and he was cleared. It was recorded that the fellows ‘in sign of unity all drank of a loving-cup together’, but the harmony was forced. Stokesley’s Oxford career was over, and Magdalen gave him two livings, a rectory and a vicarage, on the far side of Gloucestershire. The rectory was at Slimbridge, Tyndale’s possible birthplace. There is no record that Stokesley ever visited the parish, however, being content merely to draw his stipend.

Stokesley earned his rise in fortunes to currying favour with the king. He became a chaplain and almoner to Henry. Erasmus described him in 1518 as ‘well-versed in the schoolmen’, a backhanded compliment, and classified him with More and Tunstall as a credit to the court. In 1520, he attended Henry as his chaplain to the Field of the Cloth of Gold, the lavish Anglo-French spectacle of jousts, feasting and fruitless diplomacy held in a field near the present motorway exit to the Calais docks. He thrived on the king’s ‘great matter’. He travelled to France to persuade universities to come out in favour of the divorce, claiming to be the ‘principal cause and instrument’ of winning them over. On the same mission to Italy in 1530, he boasted that he had ‘recovered’ the king’s cause ‘when it had slipped through the ambassador’s fingers and was despaired of’. He used Wolsey’s ‘lack of such forwardness in setting forth the King’s divorce as his grace looked for’, so William Roper wrote, to ‘invent some colorable device’ to turn Henry against the cardinal. This he then ‘to his grace revealed, hoping thereby to bring the King to the better liking of himself, and the more misliking of the Cardinal; whom his highness therefore soon after of his office displaced …’. Stokesley was rewarded with the bishopric of London.

In September 1533 he christened the future Queen Elizabeth at Greenwich; he was a royal councillor and a leading member of Convocation. He accepted the royal supremacy and induced the London Carthusians to submit to the king. He failed to support More’s stand over the supremacy and made no attempt to protect his erstwhile ally. Stokesley had, moreover, particular reason to be careful at the time that Phillips was commissioned.

Cromwell disliked him – he found him awkward on doctrinal change – and informers were watching him and listening to his sermons. Stokesley was required to send the king a copy of a sermon he had preached. He excused himself by saying that he never wrote out his sermons. ‘If I were to write my sermons,’ he said, ‘I could not deliver them as they are written, for much would come to me without premeditation much better than what was premeditated.’ Throughout 1535, Cromwell continued to subject him to ‘vexatious proceedings’ of this sort.

Stokesley had also run foul of Queen Anne. She secured the release of Thomas Partmore, a former member of Gonville Hall at Cambridge and the parson of Hadham in Hertfordshire. Partmore had been accused of heresy by Stokesley in 1530 and had languished without trial in the Lollards’ tower. After securing his release, Anne passed Partmore’s petition on to the king. Henry ordered a commission of nine men to be set up in 1535, whose members included Cromwell, Cranmer and Hugh Latimer, to investigate Partmore’s charges of mistreatment against Stokesley and his vicar general, Foxford. It is fanciful to suppose that Stokesley, who had founded his career as a royal toady, should turn on his master and risk his neck by conspiring to destroy Tyndale.

But if not Stokesley – then who?

One man, of course, has all the obvious attributes. Thomas More had the motive. He despised, feared and loathed Tyndale; he, and his English Testament, were the obsessions of More’s life. His

hatred was not slaked by the savaging he had given Tyndale in his

Dialogue

, nor by the half a million words he had poured into the

Confutation

; this was a mere flood of ink, where More was satisfied only by blood and the flames of the ‘shorte fyre’.

Any man who had sworn to uphold the royal supremacy would be guilty of treason, if he conspired to arrest a heretic without the authority of the king, as the supreme head of the English Church. Stokesley, and every bishop except Fisher, had so sworn. More had not. He argued in his

Confutation

that, whatever the position of the pope, the Church was still the Church. The Church had found Tyndale, ‘and his own fellow friar Barnes, too’, to be heretics; and to More, almost uniquely, heretics they remained.

At the time that Phillips came into his money, in the autumn of 1534, More was recording his thoughts in his cell in the Tower. His fury was not dulled by loss of office or by imprisonment. It was, rather, renewed by them, for they were evidence that his instincts were correct, and that Tyndale and his like were ushering the Antichrist into the seat of power. More was writing and dreaming of ‘noxious vapors’, of crashing waves and collapsing mountains, fissures in the earth, and of demons plunging the heretic ‘into gulfs of ever-burning flames …’.

We know, too, that More was a skilful user of

agents provocateurs

in the Phillips mould. This was how he had obtained Frith’s fateful treatise on the sacraments. One copy had come to him from the tailor Holt, who masqueraded as an evangelical, as Phillips had done to Tyndale – convincing him that he was ‘conformable’. More’s network was so fertile that he boasted of receiving two other copies. ‘If you have three copies of a work which I especially desired to keep secret,’ Frith had complained to More, ‘then indeed I must have traitors around me.’ More’s agents also brought him copies of letters that John Frith received from Tyndale and George Joye in the first part of 1533, even though Tyndale had taken care to address his to ‘Jacob’.

Stokesley took no initiatives to have Frith executed. It was More who used the treatise to ensure that Frith went to the stake. He did so when he had been out of office for many months, in the pursuit of a personal vendetta rather than State policy. His resignation as chancellor did not curtail his hunt for heretics, and his use of agents and subterfuges.

He boasted of this, as we have seen, in the letter to Erasmus after his fall, in which he said that he wished to be ‘as hateful to [heretics] as anyone can possibly be’. We know that he regarded any tactic – perjured evidence, the use of informants and lowlifes, illegal arrests and detention, disregard for safe conducts – as fair in this war.

More revelled in burnings. The leather seller Tewkesbury ‘burned as there was never wretche I wene better worthy’; Hitton, the ‘devil’s stinking martyr’, was pleasingly to suffer ‘ye fyre ever lastynge’ after the ‘shorte fyre of Maidstone’; Frith, whom all the rest of England seemed to love, was a ‘proud, unlearned fool’ for whom ‘Cryste will kyndle a fyre of fagottes … & make hym therin swete the bloude out of hys body’.

In terms of local knowledge and contacts in the Low Countries, More was well placed. He had spent several months in Antwerp, if some time before, and we know that Vaughan suspected Bonvisi of financing Peto and Elstow. More corresponded with Bonvisi and he had sent books to Peto. Peto, Vaughan said, was ‘much helped out of England with money’. By whom, if not by More? More had, too, political renown among Catholic statesmen. In particular, he was highly regarded by Charles V.

Whoever betrayed Tyndale clearly enjoyed the confidence of the imperial government. The empire had no great reason to bother itself with Tyndale. His heresy had been directed entirely at England. The translator had made no attempt to spread his views among the emperor’s subjects. He kept to himself, and to the small English community, and he had proved a most discreet

expatriate. The pope might be happy enough to see him burnt, but he was no more than a symbolic irritant to the secular powers. He had done them no damage.

After the arrest, it is true, English appeals for clemency ran into the sands. Charles V’s ill feeling towards Henry remained. Imperial subjects had been burnt at Smithfield for heresy, and the English could not complain too strongly if there was a measure of reciprocity at Vilvoorde.

But the taking of Tyndale was bothersome: it involved assembling a snatch squad to make sure that the victim was taken in the street, and not within the sensitive confines of the English House; it upset relations with the English merchants, it led to petitions, and inquiries from Cromwell. Antwerp had a floating population of English heretics. Tyndale alone was seized.

To arrange it needed influence, as well, no doubt, as some palm-greasing by Phillips. More was admired by the emperor personally. Charles V had written him a letter of support and encouragement for his efforts on Queen Catherine’s behalf, while he was still chancellor. More had tactfully declined to receive it from Chapuys, but the ambassador made it clear that More remained ‘loyal’ and ‘affectionate’ to the emperor. ‘He begged me for the honour of God to forbear,’ Chapuys reported to Charles, ‘for although he had given already sufficient proof of his loyalty that he ought to incur no suspicion, whoever came to visit him, yet, considering the time, he ought to abstain from everything which might provoke suspicion; and if there were no other reason, such a visitation might deprive him of the liberty which he had always used in speaking boldly in those matters which concerned your Majesty and the Queen.’ More went on to pledge his most ‘affectionate service’ to the Emperor.

The arrest of Tyndale would have been a fitting

quid pro quo

for a man who had fought as best he could for the emperor’s aunt, and who now risked death for the emperor’s religion.

*

Henry Phillips told Tebold that his mysterious benefactor had commissioned him to effect the arrest of Barnes and Joye, as well as Tyndale. Barnes, too, fits More. The ex-chancellor hated him.