Bracelet of Bones (17 page)

“Cock-a-doodle-doo!” he crowed as loudly as he could.

Red Ottar screwed up his eyes and got to his feet.

“Cock-a-doodle-doo!”

“Come down!” shouted the skipper. “At once!”

“Cock-a-doodle-doo!”

But after the cock had crowed for the third time, Bard’s courage began to ooze out of him. His stomach lurched and loosened. The wet brown glue slipped down the mast.

When Bard did at last come sliding down, his tunic and hands and legs were fouled. Red Ottar made him bend over, bare-buttocked, and he whipped him. Then he picked Bard up, light as thistledown. “Wash yourself!” he barked, and he dropped the boy overboard.

“You can be sure,” Red Ottar told Odindisa and Slothi, “this is the last time any child sails on this boat.” The skipper glared up at the mast. “As for that . . .” he said.

“Rain later,” Mihran reassured him. “Rain will wash it.”

“No,” said Red Ottar. “The pennant.”

“I’ll make do,” Torsten told him. “I’ll lash a strip of cloth to the prow until we reach Kiev.”

From day to day, the river broadened. It grew so wide—fifty paces maybe—that not even Bruni or Torsten could throw a stone across it. Then it grew again, so that the crew could no longer exchange greetings with people fishing on the riverbanks.

As the gloomy pines and firs drew back, they swept past pretty green willows lining the banks, solitary farmhouses, huddles of huts, and here and there meadows of scarlet poppies and golden mustard flowers.

And when they dropped anchor early each evening to eat and rest, the light was still bright, the air mild and quite sweet.

“Chestnut,” Mihran told Bergdis. “Flowers of chestnut. You know?”

Bergdis shook her head.

“The nuts are good to eat. In Kiev you see.”

“Kiev,” said Bergdis tartly, “it’s made of your promises.” Then she held up her hands and clapped them and pretended to blow the whole city away.

Mihran turned to Red Ottar. “I will arrange you to meet Yaroslav, king of the Rus,” he said thoughtfully. “I try.” He rubbed his right thumb and forefinger together. “Merchants favored by the king make much money.”

Bruni hiccupped. “Is he the king who chose to be Christian, so we can all drink good ale and not milk or moldy water?”

“No, no,” said the river pilot. “That was his father, King Vladimir.”

Bruni hiccupped again and raised his drinking cup to good kings.

“Half alive, half dead,” Odindisa told Red Ottar.

The skipper gritted his teeth. “The worst of both worlds,” he said. “What am I to do?”

For a while the two of them looked down at Vigot.

“I doubt he’ll stand again,” Odindisa said. “Not without sticks. He can’t move his legs.” Then she took Red Ottar’s arm. “Sometimes,” she said warmly, “not deciding is best. Sometimes we know tomorrow what we don’t know today.”

Red Ottar sniffed.

“Pray to the gods.”

“I will not strike his hand off,” the skipper told her. “It’s the law, I know, but it would be dishonorable.” He sucked in his cheeks. “So what’s my choice? To leave Vigot in Kiev . . . or carry him home.”

“Wherever that is,” said Odindisa.

“Either way,” observed Red Ottar, “we’ll have to find a man to take his place.”

As the River Dnieper swept down to Kiev, Red Ottar and his companions could see mile after mile of earthen banks lining the eastern shore.

“Snake Ramparts,” Mihran told them. “King Vladimir built them to slow down the raiding Pechenegs and their ponies.”

After this, the river stretched wider and wider.

“Floodplains,” Mihran explained. “Water meadows. Now this river is five miles across. In winter, just one half mile.”

Since the portage, Solveig had seen no more than a few little fishing boats each day, but now she saw more and more skiffs and coracles bobbing along the skirts of the river, with one or two men fishing from each of them.

And then . . . then they were there!

A whaleback of a hill rose behind the west bank of the river, and at its foot were crowded quays with single-masted and two-masted and three-masted ships tied up alongside them.

Quickly Bruni and Slothi pulled down the sail; then they sat to their oars, with Red Ottar and Bergdis in front of them. Solveig watched eagerly as Mihran and Torsten allowed the boat to slip just a little past a landing stage before swinging her around and having the oarsmen paddle back upstream.

Around them, the water spit and sparkled and spun in whorls off the ends of oars.

Father, thought Solveig, did you see all this? All the people? All the boats? What did you think? What did you say? Did you know what this journey would be like before you began it?

Solveig was aware that Edith was standing on one side of her, Brita on the other. She saw all the people milling on the

quay, some shouting, some waving, and she choked with excitement and felt almost tearful.

Then Mihran threw a line to one of the harbormasters, and Edith fiercely clutched Solveig’s arm.

“What?” asked Solveig.

“Look!”

Solveig looked where Edith was pointing, and at once she saw.

“Edwin!” she cried. “Sineus!”

Red Ottar shipped his oar and stood up.

“In the name of the gods,” he roared, “how did they get here before us?”

17

R

ed Ottar was standing with one foot on the gangway, talking to Edwin, when Mihran came hurrying—skipping, almost—along the quay.

“Yaroslav, king of the Rus, will see you,” he announced. “He will receive you at noon.”

“Today?” asked Red Ottar.

“Today,” said Mihran. “Noon or never. This afternoon he will be fitted.”

“Fitted?”

“His new armor. And early this evening he shares his table.”

“Ah, yes,” said Edwin. “With me.”

“With you?” exclaimed Red Ottar.

“Me,” said Edwin with a bucktoothed smile, “or another man with the same name.”

“What are you up to?” asked Red Ottar.

“Many a loaf,” Edwin replied, “has been spoiled for being lifted from the oven too early.”

“You schemer!” said Red Ottar, not wholly without respect.

“And tomorrow,” Mihran continued, “the king sails north.”

Then Solveig and Bergdis and Slothi all came trooping off the boat with wares for their stall, and the skipper made way for them.

“King Yaroslav will see me,” he told them. “At noon.”

Bergdis dropped the furs she was carrying and threw her arms around Red Ottar. “Praise the gods!” she screeched.

“I will,” said Red Ottar drily. “But first, I’ll praise Mihran.”

“Will the king buy from us himself?” Bergdis asked. “And his queen?”

“Time will tell,” Red Ottar replied.

Then Mihran held up his right hand. “King Yaroslav also require you,” he told Red Ottar, “to bring with you Solveig, Halfdan’s daughter.”

“Solveig!” exclaimed Bergdis angrily. “Why her?”

Solveig could scarcely take her eyes off King Yaroslav. He wasn’t particularly tall or short, fat or skinny, hairy or bald, but he had the brightest blue eyes she had ever seen, brighter even than Torsten’s.

A large circular earring hung from his left ear, and it was inlaid with a stone that matched his eyes.

The king was sitting on a very high golden bench, and beside him perched his twelve-year-old daughter, Ellisif. She was wearing gold necklaces and gold armbands, and her fair hair was swept back and braided so that it looked like a whole cluster of swirling snakes. She couldn’t quite touch the floor with her pointed shoes.

Red Ottar and Solveig, accompanied by Mihran, knelt in front of the king, and all around them in the great hall of the palace stood groups of counselors, retainers, and servants.

“Stand!” King Yaroslav told them. “Welcome!”

How deep his voice is, thought Solveig. Like an ox. Mihran says he has been king since before I was born.

To begin with, the king almost ignored Red Ottar. He gazed at Solveig with his deep-set eyes, and then he beckoned her. Scarcely daring to breathe, Solveig stepped up to him, and he nodded and rubbed his trimmed beard.

“Mmm!” he rumbled. “Light-footed, not limping. Whippety. Quick-fingered, not clumsy . . .”

Solveig began to shiver.

“But,” said the king, inspecting Solveig further, “the way you tilt your head a little to the left. The way you watch.”

Now Solveig was trembling.

King Yaroslav smiled. “Like father, like daughter,” he growled. “If you’d come into this hall with one hundred other girls, I’d still recognize you. Halfdan’s daughter!”

“Oh!” gasped Solveig, and her legs almost gave way beneath her.

The king patted the bench beside him, and Solveig sat down on the padded purple velvet.

She swallowed loudly. “You met him,” she whispered.

“Any friend of Harald Sigurdsson is a friend of mine,” the king replied. “But your father—he was much more than that. At Stiklestad, he saved Harald’s life. Isn’t that so?”

Solveig nodded and swallowed again. She felt quite sick.

“Look at me, girl,” said the king.

Solveig raised her eyes.

“Yes,” said the king, with a wry smile. “‘A bit of changeling. Eager as a colt. Her voice clear and bright as a ray of sunlight.’”

Once more, Solveig was trembling. She couldn’t help it.

“Your father is well,” King Yaroslav told her. “He came here at the end of autumn on his way to Miklagard. He was in the company of Earl Rognvald—”

“I met him,” said Solveig. “For one night I did. But I was only nine then.”

“Earl Rognvald and twenty Norwegians,” continued the king. “They’d planned to meet in Sweden—”

“Over the mountains!” exclaimed Solveig, but then she put her hand over her mouth. “I shouldn’t interrupt you.”

“Some thoughts matter so much,” said the king, pursing his lips, “there’s no stopping them. As things turned out, they all made their own way to Ladoga. Yes, Solveig, your father was eager to see Harald again. Harald Sigurdsson, leader of the Varangian guard!”

Solveig gasped and clapped her hand over her mouth again.

“Yes,” said the king. “That man! So, Solveig, I praised your father’s resolve, his loyalty, his honor . . .” He paused and turned to Red Ottar. “This girl,” he said, “is the daughter of a determined, loyal, honorable man, and she is no less so herself. A young woman, traveling from Trondheim to Miklagard—I’ve never known the like of it.”

Red Ottar inclined his head and slowly nodded.

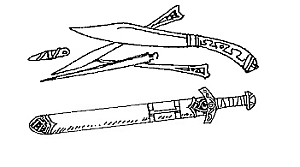

“I rewarded her father,” the king told him. “I gave him a saber.”

Red Ottar frowned and pushed his head forward.

“A curved blade,” said Mihran under his breath.

“Made by one of my own smiths,” the king went on. Then he turned back to Solveig and considered her carefully. “I asked your father,” he said, “whether he had any regrets.

“‘One,’ your father told me. ‘Only one.’”

Solveig gazed at the king, unblinking.

“He said he had left a fine woman behind.”

Solveig blinked.

“A fine woman,” the king repeated slowly.

Then Solveig lowered her eyes. Asta, she thought. Asta. My father spoke of her.

“A young woman with one gray eye,” the king went on, “one violet. Wide apart.”

“Oh!” gasped Solveig, and she shuddered. “Ohh!”

“Ahh!” sighed the king. “He said he left without telling her. Without explaining. He said he would regret it for as long as he lived.”

Solveig kept gulping, and for some time King Yaroslav sat quietly beside her. Then he turned to Ellisif. “You see how it is?” he asked in his deep voice. “Fathers and daughters.”

Without bothering to look over his shoulder, the king raised his right hand and beckoned. Two servants hurried forward, one carrying a tray with a pitcher and three little gilt cups on it, the other a silver platter decorated around the rim with wildflowers and laden with little cakes and roasted nuts.

The king waved again, and the servants brought stools for Red Ottar and Mihran.

As one servant poured liquid from the pitcher, Solveig saw that it was pale red and transparent.

“You know this?” the king asked her.

“Lingonberry?” said Solveig.

“Try it.”

So Solveig took a sip and immediately screwed up her face. “Sour!” she exclaimed.

“Cranberry,” the king said. “Good for thirst. Good for safe childbirth.”

“I’m not pregnant!” Solveig protested.

“I’m glad to hear it,” the king replied, and with that he turned his attention to the two men.

“Well, Ottar,” he said. “Red Ottar. Why Red?”

Red Ottar ran a hand through his red-gold hair.

“And a hot temper?”

“I know how to keep it, King. And I know when to lose it.”

“And blood on your hands?”

“No,” said Red Ottar. “Not spilled unjustly. Not the blood that stains.”

The king nodded. “A good reply,” he observed. “So, now! Miklagard!”

Red Ottar gave Mihran a sideways glance. “No,” he replied in a guarded voice.

“No?” exclaimed the king, and he was either surprised or very good at pretending to be so; Solveig wasn’t quite sure. “Why no?”

“It was never my plan,” Red Ottar said.

“If Solveig can go,” the king said, “you can go.” He planted a firm hand on Solveig’s shoulder. “You can watch over her . . . like a daughter.”

“My crew will say we have come far enough already.”

“Only weak men,” said the king, “blame their followers. Strong men have supple minds. I would have expected better of you, Ottar.”

Solveig listened, astonished. For the first time, she saw Red Ottar having no choice but to be submissive and heard him being put in his place.

“As it happens,” King Yaroslav said, “you’ve arrived here at a crucial time. A time that can be very profitable for you. Once more, the Pechenegs are gathering, thousands of them, and before long they’ll attack. I’ve sat on this throne for eighteen years, and this will be the greatest battle of all.” King Yaroslav made the sign of the cross on his chest. “May God guard me,” he said, “so that it’s not also my last.”

“Where are they now?” Red Ottar asked.

“North from here,” said the king. “North of the Snake Ramparts. Massing already on the banks of the Dnieper. You? You can scarcely go back. Upstream, rowing all the way. The Pechenegs will pick you all off. You can wait here, or you can go on.” The king paused. “Ottar,” he said, “Red Ottar, I need your help. I’m asking you to carry my messenger to Miklagard as quickly as you can. For me—my family, my followers, my kingdom—I believe it’s life or death.”

Red Ottar inclined his head, in submission or in thought. “Your messenger,” he said.

“I will send him to your boat.”

“King,” said Red Ottar, “you must allow me to talk to my crew. To do so is not a weakness but a sign of strength.”

“You can be quite sure I will reward you all handsomely,” King Yaroslav told him. “Not only that, the prices your furs and wax and honey will command in Miklagard . . .” The king shook his head as if there were no words to describe them. “Whatever cargo you’ve brought, buy even more. You will not be disappointed.”

“I’ll come back in the morning,” Red Ottar promised him.

“Come this evening,” King Yaroslav said sharply. “Send one of your crew to speak to me. I’ll have my men watch out for him.”

“As you wish,” Red Ottar said.

“And then you can leave in the morning.”

“King,” protested Red Ottar, “we’ve only just arrived. We’ve come all the way from Ladoga, and my crew is worn out. One of my men is badly injured. We’ll have to find someone to replace him.”

“Ah!” interrupted Mihran.

King Yaroslav nodded. “I wouldn’t ask so much of you if things were not desperate. But once you’ve passed the cataracts—”

“Cataracts!” exclaimed Red Ottar, looking wildly around him as if he expected them to hurl themselves right through the palace hall.

“Then,” the king told them, “you can all rest. Mihran, you will guide them?”

“I will,” said Mihran with a small bow, and Solveig wondered just how much of the king’s intentions the river pilot already knew.

“In this way,” the king told Red Ottar, “you will assist me and all the Rus—all the Vikings—here in Garthar. You will make yourself rich, and not only rich but honorable. You’ll always be welcome at my court, just like Halfdan and his saber!”

There was so much Solveig wanted to ask. About her father. About Harald and his two years serving King Yaroslav in Kiev. About the Vikings who guarded the emperor in Miklagard by day and by night.

But King Yaroslav stood up. All his counselors, retainers and servants bowed low. Then the king gently put his hand on the small of Solveig’s back and ushered her back to her companions.

Red Ottar and Solveig and Mihran all bowed to the king. Then they shuffled backward out of the great hall.

The dusty track from the palace to the quay was so steep that Solveig whooped and skeltered down it.

Red Ottar and Mihran followed at a more sedate pace.

“You have a daughter?” asked Mihran.

Red Ottar shook his head. “No,” he said, as much to himself as to the river pilot. “No son. No daughter. We’ve made sacrifices, we’ve offered the gods gifts . . . I don’t know.”

“But your baby is coming now,” Mihran said warmly. “Coming quickly.”

When they had set off for the palace before noon, the quay had been seething with merchants and customers, children, cattle and asses, cats, dogs.

Solveig had looked longingly at the wares on the stalls, so many more than at Ladoga—colored glass cups and plates, bronze bottles as tall as she was and material so filmy that it seemed to float, little pyramids of colored powders . . . Red Ottar wouldn’t stop, though, and kept hurrying her up.

Edie and I, later on we’ll look at every stall, Solveig resolved. We will.

But now! Solveig could scarcely believe her eyes. The same quay was deserted. A few mangy dogs were ranging around, sniffing and barking, one boy was trying to fly a kite, and a dozen or two people were drifting from stall to stall. As she looked more carefully, Solveig saw that most of the merchants and their wives were lolling beside their stalls in the shadow of their awnings. Some of them were dozing, some snoring, though Solveig supposed they’d wake at once if anyone came close to their wares.

“Here,” said Mihran, stretching out his arms, “everybody rests in the afternoon. They eat and drink and then . . .” The river pilot couldn’t help yawning, and that made Solveig yawn too. “The heat of the day,” Mihran told her. “That’s what we call it.”