Bread Matters (14 page)

Authors: Andrew Whitley

By contrast, gently fold and stretch a ciabatta dough as described above in order to preserve and develop the very open texture which is characteristic of this type of bread and which makes it so good for mopping up oily sauces and salads.

If rolling the dough up firmly and evenly is a knack that you have yet to master, don’t worry, the worst that can happen is that your loaf will have a rather ‘Continental’ texture – uneven and holey – and the top may be dimpled or undulating. But does this matter if the bread is for home consumption? Its appearance doesn’t alter its ability to nourish.

If, despite your best endeavours, the surface of the dough is a bit ragged, there is a simple solution: dip it in something before putting it in the tin or on the baking tray. Flour or cracked wheat, sunflower, sesame or poppy seeds, oat flakes or even nuts – all provide visual appeal and contribute to the flavour and texture of the loaf.

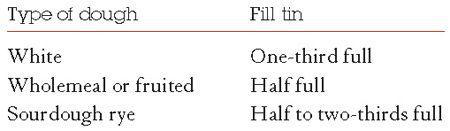

Most tin bread recipes for home bakers are based on the erroneous notion that there is such a thing as a standard baking tin. Originally a ‘small’ tin was one suited to llb (454g) of plain dough, with a ‘large’ one twice the size, and there were few variations in the shape and design available. But even that apparent standardisation overlooked the fact that a pound of white dough would expand into a much bigger loaf than a pound of wholemeal (because of the unstretchy bran and germ which constitute about 28 per cent of the latter’s flour weight). So a tin that adequately accommodates a given quantity of white dough is likely to leave the same amount of wholemeal looking a bit shrunken.

Nowadays there is such a variety of shapes and sizes available that you need to make a judgement based on the actual tin you are using and the amount by which you expect the dough to expand. Here is a rough guide:

If you don’t want to bake your loaf in a tin, you can shape it into a cob and place it on a baking sheet instead. There is a technique, known as ‘chaffing’, which is used to form a piece of dough into a tight ball to prove and bake as a freestanding cob. One hand, with fingers together and held fairly rigid at the wrist, works at a tangent to the round mass of dough. A small amount of dough at the edge of the mass is repeatedly trapped between the side of the hand and the table and stretched in such a way as to create a tension around the circumference of the dough piece. The ragged edge of dough, which is pulled away from the main mass (but not separated from it), is tucked under the main body of dough and the process is repeated until a tight cob is formed. The point of doing this with one hand (and not, as it were, ‘pushing’ with the other to help with the formation of the cob) is that dough under tension at the circumference will be less likely to stretch and allow the dough to ‘flow’ out into a flat pancake. Like other aspects of breadmaking, this is a bit of a knack, but once you get the hang of it you may enjoy the rather sensuous feeling of an amorphous mass of soft dough taking firm shape under your hands.

Proving

After being moulded, dough needs time to expand. The gluten relaxes and stretches under pressure from the gas produced by yeast fermentation. This produces a lighter, more open texture in the baked loaf. Put the bread in the oven too soon and you will get a dense (and possibly underbaked) centre and a top crust that seems to be trying to part company with the rest of the loaf. Prove for too long and the yeast will run out of food and stop producing enough gas to inflate the dough; your loaf will shrink back in the oven, leaving a crumpled and sad-looking crust.

Over-proving bread is not the end of the world: no damage is done to nutritional quality and, although the texture may be a bit crumbly, the bread is perfectly edible. However, it is a pity if your loaf ‘falls’ at the last hurdle. There is no more dispiriting sound in baking than the resigned sigh that escapes from an over-proved loaf as it cannot bear the movement of its final journey to the oven. So it is better to err a little on the side of under-proof.

To get proof right, you need to:

- Create the right conditions.

- Judge when the dough is ready to go into the oven.

CREATING THE RIGHT CONDITIONS

If the dough surface dries out, it becomes hard and cannot stretch without tearing. This leads to reduced expansion and an unsightly leathery crust. So it is important to protect your loaf from draughts or drying air. Temperature plays a role, too: the warmer the conditions, the faster the proof. Bear in mind, however, that warm places are also likely to be dry ones and that if a loaf is proving fast it is easy to miss the precise moment when it is ready to go into the oven. Don’t get hung up on creating a warm place; loaves perched above stoves or snuggled against radiators may get warm too quickly or too unevenly, and fast-proved bread can have a crumbly, cakey texture. A cooler, more even temperature may give better results. It is quite possible to prove bread in the fridge over several hours.

To keep the surface of the dough moist and stretchy during proof, you need to enclose the tin or baking tray in a large polythene bag, which will create a ‘fug’ and recycle any moisture evaporating from the loaf. The easiest way to make sure that the polythene doesn’t stick to the dough is to blow the bag up like a balloon and seal it to keep the air in. Your warm, moist breath will bring a little extra humidity into the bag, helping to stop the dough surface from drying out and so preventing a good rise.

You can achieve the same effect with a plant propagator that has a base that can be heated and a large, clear plastic dome to create a warm, moist environment. Put the loaf tin or tray on some sort of insulating mat so that any heat from the propagator’s warming cable is not so intense that it ‘cooks’ the bottom of the loaf. A cup of freshly boiled water placed beside the loaf will create ample humidity.

Waterproof

An original method of judging proof is given in a famous Russian cookbook and household manual from the 1860s called

A Gift to Young Housewives

by Elena Molokhovets (the equivalent of Mrs Beeton)

1

.

After moulding dough made with fine flour, wrote Elena, ‘you may put the loaves in a bucket of water (the temperature of a river in summer), where they will lie on the bottom until they are fully proved. When they float to the surface, put them straight in the oven. This method has the advantage that you can be relaxed about judging the time it takes for the bread to rise: when it comes to the surface, just pop it in the oven. Incidentally, if you are proving bread on the table, you can put a small test piece of dough into cold water; when it rises to the surface, you can put all your loaves into the oven.’

This dramatic illustration of the way yeast ferments in the absence of air does actually work, though in my experience, getting hold of the slippery floating dough is like catching fish with your bare hands.

JUDGING WHEN THE DOUGH IS READY TO GO INTO THE OVEN

To judge when dough is fully risen, it is necessary to educate your fingers. Of course, there are other indicators: how long has it been proving? How much has it grown? How much do I expect doughs of this type to expand? But the best arbiter is your finger pad, pressing gently on the surface of the dough, feeling how far the dough is ‘fighting back’. Test a rising dough periodically during its final rise and you will notice how the resistance changes. At first, the dough feels tight and unforgiving and any impression made by your finger quickly disappears. As time goes on and the dough inflates, you feel a springiness but still a definite counter pressure, as if the dough is determined to hold your finger at bay. Nearing the limit of proof, you sense a growing fragility and the whole structure of the dough quivers slightly if moved.

Cutting

Some loaves are cut just before they are put in the oven. The purpose of cutting the top surface of a loaf is to enable it to expand further than it might be able to if left uncut. Even when sufficient humidity has been provided during proving, the dough surface always acts as a kind of skin, restraining the expansion of the middle of the loaf. If the surface is not cut, it may split randomly during baking. This can be quite attractive. However, you get two further benefits from cutting. More crust means more flavour; and cuts can be decorative, with every slight variation marking the loaf out as an individual. Certain patterns of cuts are closely associated with particular loaves – for example, baguettes and bloomers. In the days of communal ovens, people used to mark their loaves with a distinctive cut so that they knew that they would get out what they put in.

Baking

Baking turns wet dough into firm, edible bread. As the dough begins to feel the effects of oven heat, gas production by the yeast increases in speed, ending completely when the dough reaches about 55°C. The surface of the dough is heated first and begins to form a shell, but it takes much longer for the centre to get hot enough to kill the yeast, so for a time there is a continued gas pressure from the middle of the dough to the outside. This final yeast fermentation, coupled with the pressure of water in the dough turning to steam, creates ‘oven spring’, an increase in volume that is indicated by a moderate (and attractive) tearing of the dough at the ‘shoulders’ where the sides meet the top crust.

Bread goes brown on top when baked for two reasons. First, reactions (known as Maillard-type reactions) occur between amino acids and sugars in the surface dough. Second, when the temperature is above 150°C, caramelisation of the sugars begins. A pale crust is usually a sign that there was insufficient sugar left in the dough to support these reactions. This may be because the dough has been over-fermented, or because the flour itself was deficient in the enzymes necessary to convert starch into maltose (the main sugar involved). If you get pale crusts even after shortening the overall fermentation time, you can add extra enzymes naturally by using a small amount of diastatic malt (see page 94). Enriched breads such as hot cross buns and stollen, which are sweetened with added sugar, will go brown more quickly and so should be baked at a lower temperature than plain breads.

Considerable effort is expended by some home bakers to get steam into their ovens. I am not a fan of baguette-type crusts, so I do not intend to contribute to what I regard as a fruitless exercise. The theory behind steaming is as follows: if you flood the oven with super-heated steam, it condenses on the surface of the dough (the coolest thing in the oven) and forms a kind of gel with the starch. This, being initially wet, slows down the rate of crust formation but eventually dries out into a very thin and shiny layer, behind which a thicker but less crisp crust forms. The key requirement in this process is to keep the oven tightly closed and full of steam for 10 minutes – something that is impossible in domestic ovens. So most of the suggested strategies for introducing steam are doomed to failure. A certain gloss and crispness of the crust may result if you pre-heat a heavy cast-iron tray and then squirt boiling water on to it as you put your loaves into the oven, but you still have the problem that most of the steam thus generated will almost immediately seep out of the cracks round the door or up the vent.

Some ways of creating different crust colours and textures are discussed in Chapter 9.

Suffer the little children

Arriving for a holiday in a small French village some years ago, I made a beeline for the

boulangerie

. I was surprised that the bread counter was awash with rather regular-looking baguettes. I explained that I was a baker and asked to see the wood-fired oven. The owner ushered me rather sheepishly into the bakehouse and I immediately realised that his oven was cold. ‘How did you bake all those?’ I asked, pointing at the serried sticks. ‘Oh, I buy those in frozen and bake them off in a little electric oven,’ came the reply.

I made a rapid exit and sought out some genuine artisan bread in the nearby town. My children were not as po-faced as I and ripped into ‘fresh’ baguettes with glee. Within two days, they couldn’t eat another morsel. The roofs of their mouths were red and bleeding, lacerated by the razor-sharp crusts twice-baked into those industrial baguettes.

I’m a bit of a no-pain, no-gain person myself, but I draw the line at a technology that turns daily bread into an instrument of torture.

How do I know when it is baked?

There is hardly a recipe book that doesn’t suggest tapping a loaf on its bottom to check whether it is properly baked. A hollow sound is supposed to be the clue. There is nothing wrong with this, and indeed I find myself doing it instinctively: after all, a gentle pat on the bottom is a most satisfying gesture of intimacy and approval. The problem is in determining what ‘hollow’ really sounds like. I have come across brave attempts to qualify hollowness with words such as ‘sonorous’ and descriptions of the vibration patterns in a baked loaf that border on the nerdy. But, apart from experience, a little common sense is really all that is required. In addition to the obligatory tap on the bottom, I recommend the following simple checks: