Bread Matters (9 page)

Authors: Andrew Whitley

Wheat flour

Flour is produced from a large number of wheat varieties, grown in different soils and climates (for other grains, see below). Millers select and blend different varieties and batches of grain to create flours for all purposes, from biscuits and cakes to bread and pasta. Unfortunately, there is no international classification system for flour, so it can be hard to grasp the different properties and uses denoted by a bewildering array of names and descriptions.

In order to make a judgement about the nutritional quality and likely baking performance of a flour, the home baker needs answers to the following questions:

- How was it milled? Stoneground for better retention of nutrients, or roller- milled?

- What is its ‘extraction rate’ – i.e. how brown is it?

- What is its protein content? What sort of a dough will it make? Strong and tight or soft and extensible?

If a flour has been stoneground, this will almost always be advertised on the bag since it is, rightly, deemed to be an advantage and therefore a selling point. The other two issues are more complicated.

Extraction rate

Extraction rate is the term used in the UK to denote the amount of the original grain left in the flour. Milling between stones gives a flour with all the constituents of the original grain mixed together: the mill has ‘extracted’ 100 per cent of the grain. This is known as a high extraction rate flour. To make white flour, the mill strips and sifts out the germ and the bran layers on the outside of the wheat grain which together constitute about 28 per cent of the grain, leaving a 72 per cent’ extraction flour. There are various grades in between: brown flour has some of the bran and germ replaced to take it back to about 80 per cent of the original grain.

The problem for the home baker is that, apart from ‘100 per cent whole- meal’, extraction rate is rarely mentioned on flour bags in so many words. Indeed, words like ‘brown’ and ‘mixed grain’ actually confuse the issue, perhaps sounding a bit nearer to ‘whole’ than they really are.

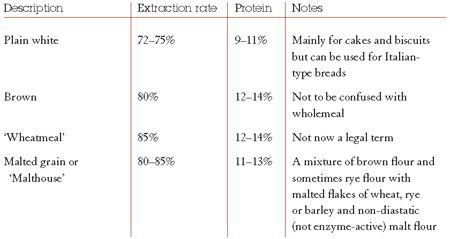

Here are some typical UK flours with their approximate extraction rates and other details:

Self-raising flours are usually lower-protein flours (white, wholemeal or brown) with added baking powder. They are designed for making cakes and scones.

Incidentally, ‘wholewheat’ is the term Americans use for wholemeal. It is specific to wheat, of course; the British wholemeal can be applied to any grain, hence wholemeal rye flour, wholemeal buckwheat flour. Latterly the term ‘wholegrain’ has emerged as an alternative. Thus ‘wholegrain wheat flour’ is the same as what the British call ‘wholemeal wheat flour’. If you find this confusing, wait until you see industrial millers and bakers touting products made with ‘white wholegrain flour’. It is already happening, in defiance of language if not of nutritional good sense. The flour thus named claims to be milled from a variety of ‘white’ (light-coloured) American wheat using a process that grinds the bran so finely that it becomes invisible. Expect a revelation in due course that rather less than 100 per cent of the wheat grain ends up in this ‘wholegrain’ flour.

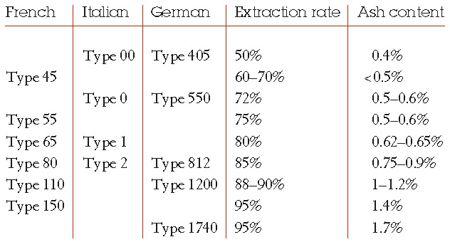

The flour classification system used on the Continent is based on ‘ash content’, a measurement of the minerals left when all the other constituents of flour are burned. The lower the number, the lower the mineral content, reflecting the degree of refinement of the flour, and therefore of its loss of nutritional value (the lower the ash content, the less nutritious the flour).

The problem with the Continental system is that, while it tells you a good deal about the presence or absence of the branny parts of the grain, which contain all the minerals, it says nothing about the protein content of the flour. Which is a pity, because for bread baking, much depends on the quantity and quality of flour protein.

Protein

Protein is important because of its relationship to gluten. The more protein there is in a wheat, the more gluten there will be in a dough made from it.

The terms ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ are often used to differentiate between types of wheat. They reflect the physical character of the grains and have become associated with their baking properties. Hard wheats are generally high in protein and have flinty grains that do not break up easily. Soft wheats are lower in protein, with grains that are plump and quite easily crushed.

Durum wheat, despite the etymological link, is not the same as hard wheat. It is a distinctly different variety of the

Triticum

species

(Triticum turgidum L. var. durum),

which is used mainly in pasta manufacture. Durum wheat is high in protein and has the particular quality that its endosperm, the floury material in the middle of the grain, does not immediately reduce to a powder when milled. It holds together in granular lumps called semolina. This can be further milled to a fine flour, but is often used as it comes. Pasta types such as spaghetti and macaroni are extruded – i.e. a stiff dough is forced through nozzles and comes out in the form of tubes. For this process to work, the dough must not be springy or elastic, otherwise it would simply compress in a rubbery mass and block the nozzles. The semolina from durum wheat produces a coherent but not very stretchy dough, which can be extruded and which holds together well afterwards. Rather surprisingly in view of its coarse texture, semolina can also be used to make bread.

The two components of wheat protein that concern the baker are gliadin and glutenin, which together form gluten, the grey-brown web of stretchy material that traps the carbon dioxide gas produced by yeast fermentation and so enables dough to increase in volume. There is an absolute correlation between protein quantity and loaf volume: the higher the flour protein percentage, the greater the potential loaf volume. However, this is where things get a little complicated.

Glutens vary according to their extensibility (how far they will stretch without breaking) and their elasticity (their propensity to spring back when stretched). For most baking purposes, the ideal dough is one that stretches easily, stretches a long way without breaking and doesn’t shrink back. To get maximum volume in a loaf, the gluten matrix must be capable of stretching ever wider (and therefore thinner) without rupturing and letting the fermentation gases escape. Its ability to do this depends partly on the variety and origin of the wheat and partly on the way the baker manages the development of the dough.

As far as the innate properties of the wheat are concerned, hard varieties, often associated with growing conditions in continental climates such as North America, Australia, Ukraine, generally produce ‘strong’ gluten, which holds together well as it stretches, but can be very elastic, with a marked tendency to shrink back. By contrast, the soft wheats of England and France tend to produce gluten that will stretch a long way but can rupture easily and has relatively little elasticity. Flours made from such wheats are often called ‘weak’.

I hope that it is becoming clear that flour quality should not be seen in simple hierarchical terms, as if hard/strong is always better than soft/weak. If this were true, we should presumably not envy France its traditional

pain de campagne,

nor Italy its focaccia, both examples of flattish breads with an open, holey crumb – the product of precisely the kind of gluten formed from locally adapted varieties of wheat.

Most British flours are milled from blends of UK and imported (often Canadian) wheat and are designed to produce a typically British loaf – very aerated with a close, even texture and, heaven forbid, no holes. However, they may well have too much protein, or too strong and elastic a protein, to produce the best results in open-textured Continental styles of bread. The obvious solution, if you are aiming for authenticity, would be to seek out specialist flours milled abroad, always remembering that you will probably be buying flour milled to a certain style rather than from the wheat of the nation concerned. However, such flours are not widely available, though some British mills do supply their own blends of flour for ciabatta and the like.

One alternative would be to mix a strong flour with a lower-protein ‘plain’ flour or one that does not have the word ‘strong’ in its title. Check on the nutrition information panel to establish the approximate protein percentage. Another possibility is to try flour from a small British watermill or windmill. Often these mill organic wheat and, since they have limited grain storage space, their flour is not usually blended; in other words, it is milled from single batches of wheat, which can often be traced to a specific field on the farm. These small mills almost always use stones for grinding and so preserve the maximum amount of nutrients in the flour, and they are unlikely to throw in any additives such as amylase enzymes. The one drawback (if it is a drawback) of single varieties is their unpredictability: one batch may be superb, another rather less so.

The summers of 1975 and 1976 were warm and dry and the English Maris Widgeon wheat with which I started serious baking was strong and sweet. It was only when we hit the wet harvest of 1977 that I had any real inkling of the pitfalls of using local wheat. Suddenly, my loaves were shrinking in volume and occasionally they even had holes just under the crust. At that time almost all my bread was baked in tins; ciabatta and rustic French styles were a decade away. So the weak, sloppy gluten of those British flours could not be put to good use in holey flat breads. I had to sharpen my skills to ensure that the bread held together.

English wheat

‘Today on his table he has the best wholegrain bread I have ever tasted, baked by his wife. The good miller, he said, milled the whole grain palatably, hygienically and digestibly from fresh wheat locally grown. But it would not keep (good things to eat seldom do). The modernised millers imported the dry Canadian wheats, which will store and travel, standardised the moisture content and extracted the offals with the germ to be resold. Big business sprang out of lifeless bread.’

H. J. MASSINGHAM,

The Wisdom of the Fields

(Collins, 1945)

Flavour

It is striking that in professional manuals and domestic baking books alike, there is rarely, if ever, a mention of the flavour of flour. True, many factors contribute to the flavour of a baked loaf, not least the length and method of fermentation. But flour is by far the largest component of bread, and since much bread is made with white flour, which is intrinsically pretty tasteless, one might have thought that some attention would be paid to the differences in flavour between various wheat varieties. It seems, however, that the average British consumer rather favours blandness. Some years ago a large independent bakery firm did some trials with a sourdough system for making standard white sliced loaves, but did not adopt the new method when taste panels reported that the bread had ‘too much flavour’.

For those home bakers who

do

want to make the best-tasting bread, I recommend British wheat every time. It goes without saying that I mean good, organically grown British wheat. Any wheat grown in a cold, sunless summer, harvested too late and needing to be dried mechanically is unlikely to taste wonderful. But there is something about the conditions in the better kind of British summer that, combined with the right soil and a suitable wheat variety, can produce flour that tastes superb. And I do mean British, not just English. Some of the highest-protein wheat in Britain has been grown on the Black Isle (north of Inverness), whose microclimate and extended summer day-length must be partly responsible

1

. I hope that the work currently being done in various European countries to develop wheat varieties more suited to organic systems will not forget to include flavour as a key criterion.