Bread Matters (12 page)

Authors: Andrew Whitley

In the recipes in this book, I suggest using butter in plain English-type breads and rolls and olive oil in Italian ones. You can happily use olive oil throughout with a small, but I would say quite acceptable, sacrifice of volume.

Oils

Olive oil, especially cold-pressed extra-virgin oil, imparts a wonderful flavour to bread, subject to my remarks above about baking destroying some of it. If you can afford it, always use olive as your liquid oil in breads. Sunflower oil is not a bad alternative, especially the unrefined version, though bear in mind that this can go rancid much quicker than olive oil. Organic sunflower oils are usually ‘deodorised’ by a steaming process, which is preferable to chemical refining. They keep well, but have much less flavour and colour than the ‘raw’ variant. Of course, this may be an advantage in a delicate product where you do not want too much flavour. The same applies to soya oil, which, in its raw form, gives a distinctly beany flavour that is absent in the refined version. Walnut oil is very expensive but gives a wonderful flavour to bread and is very nutritious. Safflower oil is equally rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids but milder in flavour. I avoid unspecified ‘vegetable oil’ on the principle that if the manufacturers won’t tell me what oils are included, they probably have something to hide.

These, then, are the essential ingredients of bread. Many other ingredients can be added to achieve particular flavours, textures or nutritional effects. I will deal with these as we go along, especially in the chapters on enriched savoury and sweet doughs.

Now we can get down to business. Determined to reject the deceptions and nutritional impoverishment of British industrial baking, armed with essential information about what goes into real bread, we can approach the basic processes of breadmaking, looking in particular at the way time can be used to build true quality into bread without unduly disrupting busy lives.

CHAPTER FIVE STARTING FROM SCRATCH

‘Every time a recipe is not strictly followed, every time a risk is taken with changed ingredients or proportions, the resulting food is a creative work, good or bad, into which humans have put a little of themselves.’

THEODORE ZELDIN,

An Intimate History of Humanity

(Vintage, 1998)

Before describing how to make a loaf of bread, I need to get a few things off my chest.

Over the years, I have bought, read and used a good many recipe books. I have been inspired by some and I have learned from many. But as my experience has grown, I have been increasingly bothered by certain instructions that crop up repeatedly in the baking canon. They often seem to have been sprinkled over the text like holy water in a random gesture that owes more to faith than to evidence.

These instructions take various forms. There is the bald assertion, the confident claim that is completely irrelevant, or the advice so vague that it leaves the reader bemused. Many of them are handed on from book to book until they acquire all the permanence of holy writ. Of course they do no real harm. But once you see through one of these shibboleths you wonder how far you can rely on the author’s other pronouncements.

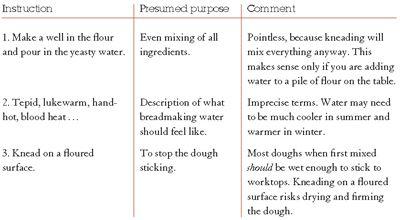

Here are a few of the worst offenders.

Eight illogical instructions

My objection to these commonly found instructions is not that they are wrong, though some clearly are. It is more that they present breadmaking as a question of simply obeying orders rather than observing and understanding. Too often these apparently authoritative pronouncements confuse or miss out the vital information that enables us to understand and take control of the process. To do that, you need to know what is happening and why.

Once you have grasped the general principles, you will be able to make bread without constant reference to specific instructions. More importantly, you will be able to adjust your methods in the light of a clear understanding of what is actually going on in your dough. Breadmaking may seem to have the precision of chemistry; in fact, it has all the variability of biology, where sympathetic adaptation works better than unthinking compliance every time.

The following explanations apply to breadmaking in general. I will add more detail, as appropriate, to individual recipes in later chapters.

Joined-up baking

In the early 1990s, French artisan bakers felt so disgusted (and threatened) by the rise of frozen and reheated ‘bake-off’ bread that they managed to get a law passed forbidding the use of the term

boulangerie

for any establishment in which the five stages of baking were not conducted in one unbroken process.

In the UK, ‘scratch’ is the term for a baking operation that uses the basic elements – flour, water, yeast, salt etc – and no prepared mixes or frozen or part-baked dough.

The five stages of breadmaking

There are five stages in making a loaf of bread:

- Mixing and kneading.

- Rising or ‘fermenting’.

- Shaping or ‘moulding’.

- Proving.

- Baking.

In this chapter I describe what happens in each of these stages. If you would rather go straight to the recipes, you can always return to these pages to check on the details.

Mixing and kneading

In home baking, kneading is the word used to describe the action of working dough to develop a structure that will enable it to rise. But before any work can be done with the dough, the main ingredients must be combined.

Mixing

It is surprising how reluctant some ingredients can be to come together. Try, for instance, mixing fresh yeast, a small amount of flour and a rather larger quantity of water to make a sloppy ‘ferment’ that will allow the yeast to bubble vigorously. If you throw all the components in together, some of the flour and yeast will almost invariably form little flinty nodules that resolutely refuse to soften. To avoid lumps, dissolve the yeast in a little of the water first, make a paste with this liquid and a little of the flour, then gradually work in the remainder of the water.

Fresh yeast, stirred around in water with a finger, will dissolve in a few seconds into a brownish liquid. Dried yeast granules will take a little longer. They will float to the top and should be left for a few minutes to swell and bubble. Fast-action yeast will dissolve almost immediately.

Stir any salt or spice called for in the recipe into the flour before you add the liquid. If you are using a solid fat, such as butter or lard, there is no need to rub it in but it will disperse into the dough better if it has not come straight from the fridge.

Now add the liquid and work the ingredients together gently with your hands. Most books recommend gradually incorporating the flour with a wooden spoon. I can’t see the point of dirtying another utensil. Your hands will get sticky anyway when kneading, so why delay?

WELL-WORN ADVICE

There is no need to ‘make a well in the flour’ for the yeasty water. Legions of home bakers have read this comfortingly precise instruction in countless recipe books and obeyed it, quite reasonably assuming that it had some purpose. But does it? After all, the ingredients are going to end up as a sticky dough, however they are mixed – by hand, with a wooden spoon or in a mixer. So why the myth of making a well?

My guess is that this is a hand-me-down from an age when bread, forming the greater part of a family’s food, would be made in large quantities, even in ordinary households. According to Eliza Acton, writing in

The English Bread Book,

the bread consumption in a country clergyman’s family in the middle of the nineteenth century was about five pounds of bread per person a week – equivalent to not far short of a small loaf each per day, or more than three times what the average person consumes now.

The family doughs of times gone by would almost certainly have been made not in a bowl but by heaping the flour on to a large kitchen table. As anyone who has mixed mortar knows, the only way to avoid a frenzied scraping round the yard is to make a well in the mound of dry material, gradually working in the liquid so that it cannot escape. So here is the justification for making a well. But if we mix dough in a bowl, there is no need.

Pre-soaking

Usually known by its French name, autolyse, this involves mixing the dough ingredients just until they are combined and then leaving them to rest for about half an hour, before resuming mixing/kneading.

Pre-soaking is a process of self-digestion catalysed by hydrolytic enzymes. In a bread dough, the flour proteins (glutenin and gliadin) come under the influence of enzymes as soon as they are wet. The changes that occur are similar to the kind of gluten ‘development’ achieved by kneading. So why not forget the kneading and leave it all to the pre-soak? Because the passive process, while useful, cannot develop gluten quality as effectively as a combination of physical and enzymic action.

Kneading

The purpose of kneading is:

- To ensure the even distribution of all the ingredients.

- To develop the dough structure.

The mechanical action of kneading, combined with the chemical reactions between the various ingredients, creates a three-dimensional gluten network from the two main protein fractions of the wheat, glutenin and gliadin. This is best visualised as a series of tiny balloons which will be inflated by the carbon dioxide gas produced by yeast fermentation. Vigorous working of the dough develops the material from which the balloons are formed. If a great deal of water is added, the structure will be very soft and, while the balloons may inflate well, they will not support much vertical lift. Conversely, a tight dough with insufficient water will prevent the full expansion of the gluten matrix, resulting in a smaller loaf.

One of the by-products of the invention of high-speed mixers for the Chorleywood Bread Process was the discovery that the rate at which energy goes into the dough significantly affects gluten development. In other words, a given amount of energy will have more effect if delivered to a dough over a shorter rather than a longer period of time. In domestic terms, this would explain why a reasonably efficient mixer will usually produce better dough than hand kneading. However strong our biceps, we cannot normally impart energy as quickly as a mechanical mixer.

MACHINE OR HAND?

Why knead by hand if a mixer does it better? There are several answers. For a start, not everyone has a mixer and it would be wrong to suggest that good bread cannot be made without one. Furthermore, only if you mix by hand will you experience the whole process of change as it occurs, and thereby develop an ability to recognise what good dough feels like. Even in modern bakery colleges, where students are prepared for the world of machines and additives, the very first assignment is usually to make bread by hand. It is also true, as many a perspiring student of mine has observed, that kneading is a good physical work-out that beats going to the gym, if only because it costs little, can be done at home and has an edible end-product.

But perhaps the most compelling reason to knead by hand if only once in your life is that bread made this way is truly yours. In using your body’s energy to mix and work the dough, you are literally giving of yourself, and a loaf made like this contains and therefore expresses you in a way that cannot be said of ingredients transformed – however conveniently – by the ingenuity of distant engineers and technologists.

HAND KNEADING

This should be fun, energetic, even therapeutic. It doesn’t much matter how you do it as long as you understand what the end result should be. Bear in mind the following points and you will not go far wrong:

- Don’t worry about sticky hands.

- Don’t add more flour until you’re sure it’s needed.

- Wetter is better.

- Try ‘air kneading’.

- Use flour to clean your hands.

- Sticky = bad; soft = good.