Breaking Stalin's Nose (7 page)

Read Breaking Stalin's Nose Online

Authors: Eugene Yelchin

DISSECTED FROGS, foul chemicals, and something else stomach-turning, all pickled in jars. The biology lab is empty. A good place to hide.

The senior lieutenant recognized me right away and opened his mouth to speak, but I didn't wait to hear. I bolted back up the stairs to this room. Nobody ever comes here since Arnold Moiseevich, a foreign spy pretending to be a biology teacher, was arrested three months ago.

Now, peering through the keyhole, I watch them marching up to the principal's office. I notice that one guard is missing. I bet he's guarding the front

door. There's a second exit through the gym; as soon as they are out of sight, I'll sneak in there, and then it's good-bye.

door. There's a second exit through the gym; as soon as they are out of sight, I'll sneak in there, and then it's good-bye.

Just then, a nasal voice says behind my back, “For some people, four walls are three too many. One wall's enough for a firing squad.”

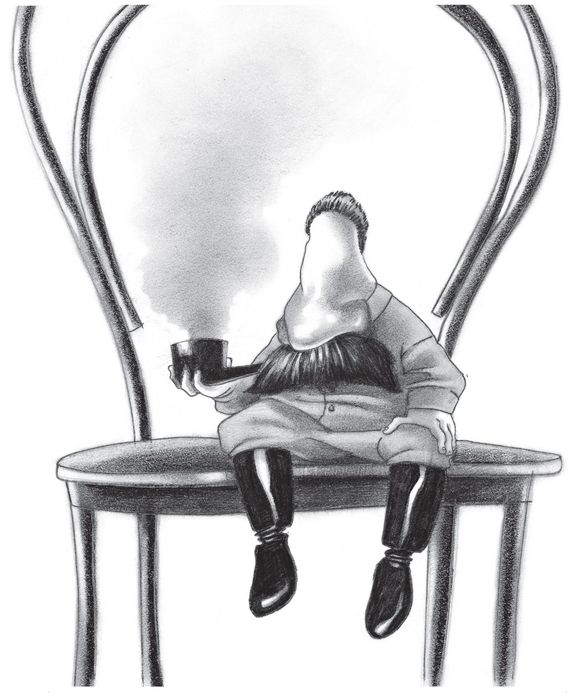

I turn around slowly. By the window hangs a cloud of tobacco smoke so thick, I can't see who is talking. Behind the smoke, a chair creaks, and the same voice says, “Do you follow me, Zaichik?”

The smoke drifts away, and now I see who's sitting in that chairâ

Comrade Stalin's plaster nose

, and it's smoking a pipe!

Comrade Stalin's plaster nose

, and it's smoking a pipe!

“Did we arrest your father?” it says. “Yes, we did. Did you report his criminal activities? No, you didn't. Careless, comrade. Complacent. And naive.”

I cough and cover my mouth. The biology lab is small and filling up with smoke fast.

“What is your duty and privilege as a Communist youth?” says Stalin's nose. It doesn't wait for

my answer. “Renounce your father, an enemy of the people, and join the Pioneers in the march toward Communism. A simple procedure.” The nose blows more smoke and rubs its boots together. “Repeat after me. âI, Sasha Zaichik, renounce my father as an agent of foreign powers and hereby sever all my relations with him. From now on my real father is our beloved Leader and Teacher, Comrade Stalin, and the Young Soviet Pioneers are my family.'”

my answer. “Renounce your father, an enemy of the people, and join the Pioneers in the march toward Communism. A simple procedure.” The nose blows more smoke and rubs its boots together. “Repeat after me. âI, Sasha Zaichik, renounce my father as an agent of foreign powers and hereby sever all my relations with him. From now on my real father is our beloved Leader and Teacher, Comrade Stalin, and the Young Soviet Pioneers are my family.'”

Carefully, I step back to the door, keeping my eyes on the nose, and pull on the door handle. The door won't budge. It's locked. The nose stares at me, waiting for me to repeat after it.

“What is my father guilty of?” I say.

“We are, at this very moment, in the process of interrogating him. He's about to confess.”

“My dad is innocent. There's nothing to confess!”

“Everybody confesses in Lubyanka. We know how to make people talk.”

Stalin's nose looks at the pipe and says, “Which reminds me of an incident. Once, I received a delegation of workers from the provinces. When they left, I looked for my pipe but did not see it. I called the chairman of the State Security. âNikolai Ivanych, my pipe disappeared after the visit of the workers.' âYes, Comrade Stalin, I'll immediately take the proper measures.' Ten minutes later, I pulled out a drawer in my desk and saw my pipe. I dialed the State Security again. âNikolai Ivanych, my pipe's been found.' âWhat a shame,' he said. âAll of the workers have already confessed.'”

Stalin's nose slaps its knee and laughs, but it's not really a laugh. It's shaking all over and smoke pumps out the nostrils. It's horrible. “Join the Pioneers, Zaichik, and forget about your father. It's not like you'll ever see him again.”

“THERE'S NO PLACE for the likes of you in our class,” Nina Petrovna says. “Go sit in the back and don't stick your spy nose into anything. Is that clear?”

I'm trying to stop shivering, but the classroom is freezing and I'm soaked through. When Agafia, the cleaning woman, found me in the biology lab, I had passed out. She doused me with icy water to wake me up. Of course I kept quiet about Stalin's nose. I don't want them to think I'm crazy, on top of everything else.

“When you hear the song âA Bright Future Is

Open to Us,'” says Nina Petrovna

,

“you begin marching. The drums and the bugles march in first, then the children who will be joining. Remember, class, our great Leader and Teacher is always watching us from the Kremlin. Make him proud. Ready? One, two, three ⦔

Open to Us,'” says Nina Petrovna

,

“you begin marching. The drums and the bugles march in first, then the children who will be joining. Remember, class, our great Leader and Teacher is always watching us from the Kremlin. Make him proud. Ready? One, two, three ⦔

They bugle, drum, and march around Nina Petrovna's desk. From the back row, the classroom looks different. I'm here with other

unreliables

and I can see much better from here. Now I can see the whole room.

unreliables

and I can see much better from here. Now I can see the whole room.

“After the song, you will hear a drumroll. This is when our sacred banner will be brought in,” says Nina Petrovna, and glances at me. “Who's going to carry the banner? Who truly deserves it? Who loves Stalin most of all?”

She's not looking at me now, but I can tell she's enjoying choosing someone else to carry the banner. Someone other than me.

I look up at our class photograph. Finkelstein's

face is covered in black ink, and Vovka's, too. Mine's next. Any minute, the State Security guards will burst through the door and drag me off to Lubyanka to confess to my crimes. I will never be a Pioneer. Do I still have to live by the rules of the Pioneers?

face is covered in black ink, and Vovka's, too. Mine's next. Any minute, the State Security guards will burst through the door and drag me off to Lubyanka to confess to my crimes. I will never be a Pioneer. Do I still have to live by the rules of the Pioneers?

I get up, walk to where the banner is leaning against the wall, take it, and climb up on Nina Petrovna's desk. I wave the sacred cloth over my head and, marching in place, sing “A Bright Future Is Open to Us” in a loud voice. It feels good.

“Zaichik!” shrieks Nina Petrovna. “Down, Zaichik! Down!”

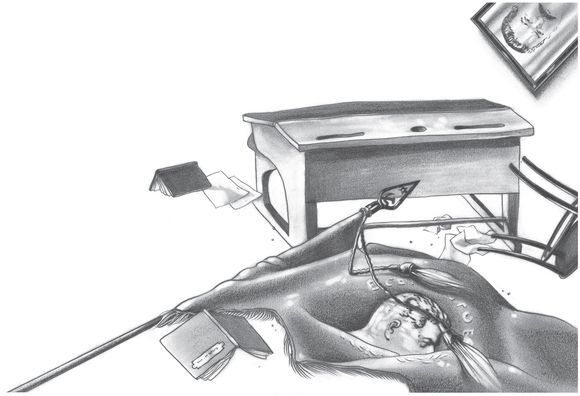

She tries to grab my foot, but I'm faster. I hop from desk to desk, shouting the song and waving the banner. Nina Petrovna chases after me. Everyone's laughing. Then I miss a desktop and go down, and right away she's on top of me, screeching and wrestling the banner out of my hands.

When the State Security guards stomp in, I'm on my back, head toward the door, so I see their

boots upside down. One of the guards is holding Vovka by the collar. “That scum there,” Vovka says, pointing in our direction. Then Vovka nods toward Nina Petrovna's desk.

boots upside down. One of the guards is holding Vovka by the collar. “That scum there,” Vovka says, pointing in our direction. Then Vovka nods toward Nina Petrovna's desk.

A guard steps over us, clomps to the desk, pulls the drawer out, and dumps it on the floor. Everyone's quiet, watching him. He sorts through the stuff from the drawer with the tip of his boot, then bends down and picks something up.

It's Stalin's plaster nose.

He shoves it into Nina Petrovna's face, which drains to white. “No. No. It's not mine. I couldn't ⦠I'm a Communist ⦠. It's a mistake.”

I look up at Vovka. He knows I'm looking at him, but he doesn't turn his head. I see he's grinning. So, he didn't turn me in after all. He must have stayed behind in the classroom and hidden the nose in Nina Petrovna's desk during Sergei Ivanych's speech in the cafeteria.

The guards twist Nina Petrovna's arms and drag her to the door. She screams and kicks and tries to hold on to nearby kids. They duck under her arms, laughing.

I DIDN'T KNOW our principal, Sergei Ivanych, is so short. He's always either behind his desk or behind the podium, delivering speeches. There must be something hidden under his seat to lift him up, because now, as he walks me down the hall, I see that he is no taller than a kid.

“Nina Petrovna didn't break off the nose,” I say.

“That woman is no longer my responsibility,” he says, and keeps walking.

“Finkelstein didn't break it, either.”

“Finkelstein confessed in front of everybody.”

“He did it to get into Lubyanka to look for his parents.”

“His parents were executed,” he says, and shrugs. “Somebody should have told him.”

I'm getting the shivers again. My teeth start to chatter. Poor Four-Eyes. His aunt told him his parents had been shot; why didn't he believe her? Now he's gone to prison for nothing.

“No stopping. Let's go, Zaichik,” says Sergei Ivanych, and he grabs my arm and pulls me down the stairs to the basement. He's short but strong.

SERGEI IVANYCH knocks softly on the storage room door: three quick knocks, a pause, three quick ones again. He listens for a moment, takes a key out of his pocket, unlocks the door, and nudges me in. “Good luck, Zaichik,” he says, and shuts the door.

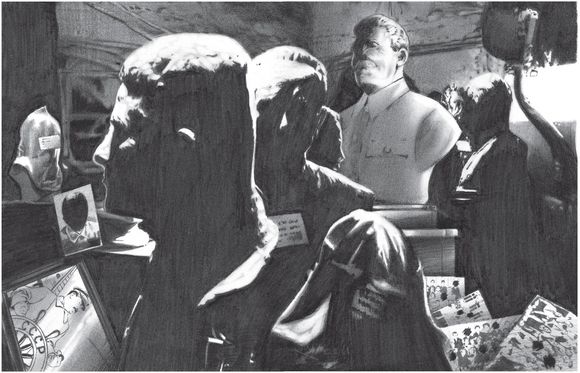

I expect to see Matveich in here, guarding state property, but, in fact, I see nothing, just darkness. I listen to Sergei Ivanych locking the door and walking away and wait for my eyes to adjust to the dark. I grope for the wall and find it clammy to the touch. I feel my way along the wall, boots wading through what feels like shallow water. Soon I bump into something large and smooth, and I turn to it. I slide my hands over the plaster crevices, and when I find the face, the nose is missing.

So this is where they hauled you, Comrade Stalin, into this dark and moldy place.

So this is where they hauled you, Comrade Stalin, into this dark and moldy place.

A faint yellow light flickers from the doorway of some room farther in. It gives off enough light for me to make out the shapes of the things around me. At my feet is Vovka's prize watercolor,

Comrade Stalin at the Helm

, the colors running in streaks behind the cracked glass. Next, leaning against the wall and buckling in the water, are dozens of group photographs, the kids' and teachers' faces blackened, scratched, or stabbed out with something sharp. It's creepy.

Comrade Stalin at the Helm

, the colors running in streaks behind the cracked glass. Next, leaning against the wall and buckling in the water, are dozens of group photographs, the kids' and teachers' faces blackened, scratched, or stabbed out with something sharp. It's creepy.

“Out of sight, out of mind. That's why they put all this stuff down here,” says a hoarse voice from the dark. “It helps people forget.”

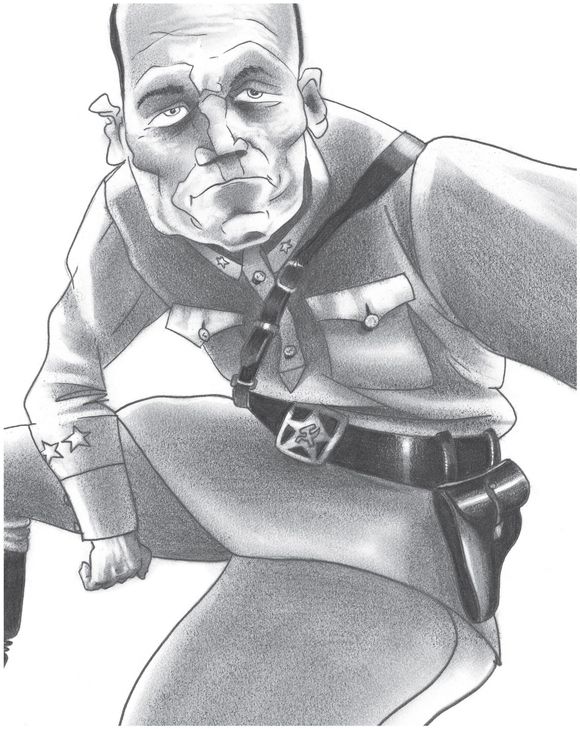

When I turn to the voice, I see the State Security

senior lieutenant sitting on a wooden crate under a dim lightbulb, smiling at me. “Have a seat, Zaichik,” he says, and waves at another crate nearby. “Make yourself comfortable.” The crate is overflowing with the lists of suspects they made us write. I hesitate and glance at the senior lieutenant, but he nods, so I sit on top of the names.

senior lieutenant sitting on a wooden crate under a dim lightbulb, smiling at me. “Have a seat, Zaichik,” he says, and waves at another crate nearby. “Make yourself comfortable.” The crate is overflowing with the lists of suspects they made us write. I hesitate and glance at the senior lieutenant, but he nods, so I sit on top of the names.

“Treat yourself,” he says, holding a small tin box with hard candies inside. “Take as many as you want.” I take one, but he keeps the box open, staring at me, smiling. I take another. “Do you mind if I read something to you?” he says.

I shrug and he takes out a piece of paper and unfolds it carefully. He clears his throat and starts reading. “âIt's not possible to be a true Pioneer without training one's character in the Stalinist spirit. I solemnly promise to make myself strong from physical exercise, to forge my Communist character, and always to be vigilant, because our capitalist enemies

are never asleep. I will not rest until I am truly useful to my beloved Soviet land and to you personally, dear Comrade Stalin. Thank you for giving me such a wonderful opportunity.'”

are never asleep. I will not rest until I am truly useful to my beloved Soviet land and to you personally, dear Comrade Stalin. Thank you for giving me such a wonderful opportunity.'”

It's the letter I wrote yesterday, which my dad was supposed to deliver to Stalin.

“I found it in your dad's briefcase.” He leans in close and pats me on the knee. “After all that's happened, do you still want to become a Pioneer?”

“I will not renounce my dad,” I say.

“You won't have to, Zaichik. In your case, we're willing to make an exception.” Speaking in a secretive voice, he continues: “We're offering you a rare opportunity to pledge assistance to the Soviet State Security. All you have to do is listen in, observe, and report suspicious behavior right here in your own school. Let your deep-felt devotion to Communism be your guide. You'll be our secret agent, like your dad. Comrade Stalin called him âan iron broom purging the vermin from our midst.' You bring us enough reports, Zaichik, and you'll get to meet Stalin, too. Imagine that.”

“My dad was never a snitch.”

“What do you think your dad's job was?” he says, surprised.

He moves his crate so it's touching mine and wraps his arm over my shoulders. This close, I can smell him. Tobacco, sweat, and something else. Gunpowder, I decide.

“Frankly, Zaichik, I used to have great respect for your dad. Two years ago, when he submitted a report on the anti-Communist activity of a certain foreign national, who happened to be his wifeâI'm talking about your mother hereâhe acted as a true Communist, willing to make a personal sacrifice for the good of the common cause.”

He's lying. “My mom died in the hospital,” I say.

He looks at me strangely and continues: “But

with time, your father's vigilance faltered and he became easy prey for your mother's spy contacts.”

with time, your father's vigilance faltered and he became easy prey for your mother's spy contacts.”

“My mother wasn't a spy.”

I try to get up, but his arm keeps me seated. “He confessed, Sasha,” he says.

“Everybody confesses in Lubyanka,” I say, repeating what Stalin's nose said.

“You know how to make people talk.”

“I understand. It's a lot to take in. But I'm giving you a chance to make the right choice. If you carry the banner today at the Pioneers rally, everybody will be looking at you and thinking, There goes Sasha Zaichik; he's one of us again.” He moves his right hand toward me, palm open, waiting for me to shake it. “If you chose not to, I'll be talking to you in the basement of Lubyanka prison. You don't want this to happen, do you, Sasha?”

I look at him. He means it. I shake his hand.

Other books

Downbelow Station by C. J. Cherryh

El espíritu de las leyes by Montesquieu

Crossing the Barrier by Martine Lewis

Erotic Research by Mari Carr

Crossbred Son by Brenna Lyons

Gypsy Wedding by Lace, Kate

Knight 02.5 - If I'm Dead by Clark, Marcia

Glenn-Stormy-Love-&-Spaghetti-on-Aisle-Eight by Stormy Glenn

The Power by Colin Forbes