Breaking Stalin's Nose (6 page)

Read Breaking Stalin's Nose Online

Authors: Eugene Yelchin

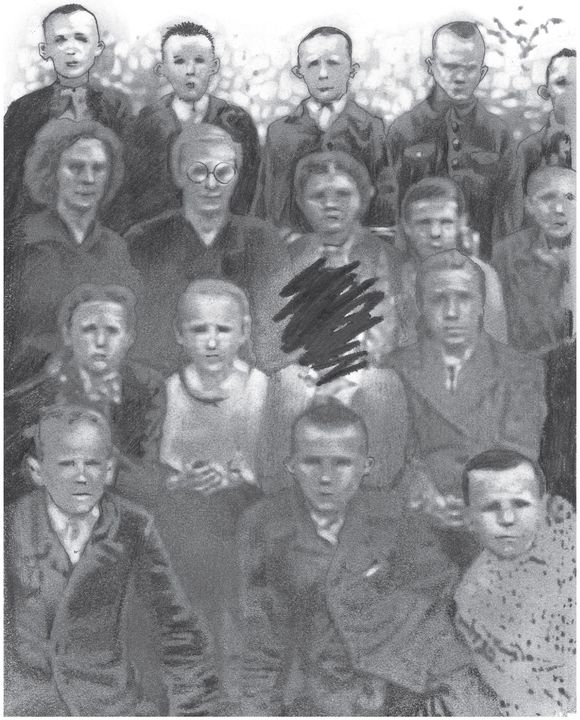

“AS THE PROVERB goes, the apple doesn't fall far from the tree,” says Nina Petrovna, looking out at us from behind her desk. “We should have known better than to permit Finkelstein to remain in our ranks after his parents were arrested. We have failed, class, slackened in our vigilance. But this will not happen again.”

Nina Petrovna rises, walks to where the group photograph of our class hangs on the wall, and blackens Four-Eyes's face with her ink pen. That's what we always do to the pictures of enemies of the people, and it usually feels good, but not this time. Four-Eyes is not an enemy. He just wanted to see his parents.

Satisfied now, Nina Petrovna turns away from the picture. She says, “Thanks to Finkelstein, we have very little time left to prepare for the Pioneers rally. But will this stop us from doing an excellent job?”

“No!” we yell.

“That's the Pioneer spirit, children. Drums and bugles, line up by the blackboard. Zaichik, bring the banner.”

We line up in a flash, eager for Nina Petrovna's next command, but for some reason she's staring at the class photograph again. I look at it, too. The black ink glistens, still wet on Four-Eyes's face. When Nina Petrovna turns around, she looks serious and determined. “Children,” she says, “your teacher has a confession to make.”

Everyone gets really quiet; we've never heard a teacher confess to the students before.

“For some time, and contrary to my Stalinist

principles,” she says, “I have been forced by my superior to keep silent.” Here she looks up at the principal's office, right above our classroom; then she looks back at us significantly, making sure that we understand she's talking about our principal. “But in view of the vicious act of terrorism that happened in our school today, I refuse to be silenced any longer. Listen carefully, children. This is something I should have told you before.” She takes a deep breath and says, “We have another individual in this class who is a child of the enemy of the people.”

principles,” she says, “I have been forced by my superior to keep silent.” Here she looks up at the principal's office, right above our classroom; then she looks back at us significantly, making sure that we understand she's talking about our principal. “But in view of the vicious act of terrorism that happened in our school today, I refuse to be silenced any longer. Listen carefully, children. This is something I should have told you before.” She takes a deep breath and says, “We have another individual in this class who is a child of the enemy of the people.”

My dad always tells me to breathe through my nose if I choke on something. This way, you won't suffocate. But this is worse than chokingâI can't breathe at all, not even through my nose. I glance at the door, judging the distance. If I run to it, she won't be able to stop me. But I don't run. Nina Petrovna says, “Sasha Zaichik!” and points her finger at me. Then everybody cranes his neck to take a good look at the child of an enemy of the people. I

squeeze my eyes shut. Suddenly, the weight of the banner I'm holding is unbearable. In the next moment, it hits the floor.

squeeze my eyes shut. Suddenly, the weight of the banner I'm holding is unbearable. In the next moment, it hits the floor.

“Pick up the banner, Zaichik,” Nina Petrovna says calmly. I open my eyes. Nina Petrovna is not even looking at me. It was all in my imagination. She's facing the back of the class, her finger aimed at Vovka instead. “Sobakin, why don't you tell us what your father was accused of? Wrecking, wasn't it?”

People gasp and turn to gape at Vovka. Someone whistles. When I finally look myself, Vovka is rising from his seat slowly, drilling into Nina Petrovna with the same scary eyes he turned on me in the boys' toilets.

“You should know, children, that Sobakin's father was executed as an enemy of the people,” says Nina Petrovna. “Does it explain his hideous anti-Soviet behavior and the likely fact he was conspiring with Finkelstein? What do you think, children?”

Before anyone has time to answer, Vovka flies at

Nina Petrovna, grips her by the throat, and begins strangling her. Nina Petrovna's face turns red and her eyes bulge. She makes gurgling noises and starts kicking up her legs. Nina Petrovna and Vovka knock things to the floor and bump into desks.

Nina Petrovna, grips her by the throat, and begins strangling her. Nina Petrovna's face turns red and her eyes bulge. She makes gurgling noises and starts kicking up her legs. Nina Petrovna and Vovka knock things to the floor and bump into desks.

Everybody jumps up; some are screaming, but most are laughing. I know the Pioneers never get involved in fights, but before I know what I'm doing, I join in and try to separate them. Now there are three of us stumbling and grunting and bumping into desks for what seems like a long time, until somebody runs out to fetch Matveich and the others. Soon they are dragging Vovka and me off to the principal's office, with Nina Petrovna staggering behind and sobbing.

WE ARE TOLD to wait while the principal talks to Nina Petrovna. They argue behind the closed door, her hoarse voice barely a whisper. I wonder if she sounds like this from Vovka's trying to strangle her. We are waiting on the same bench that I saw Four-Eyes sitting on just this morning. This morning when I came here to get the principal's signature, he was planning to get into Lubyanka to see his parents, sitting in exactly the same spot I'm sitting in now. I wonder if he's with his dad already.

I steal a glance at Vovka. “Sorry about your

dad,” I say. He doesn't even look at me. He sits there, chewing on his nails.

dad,” I say. He doesn't even look at me. He sits there, chewing on his nails.

I understand how he must feel. If my dad were shot, wouldn't I be angry? What's hard to believe is this: Vovka's dad, an enemy of the people? When Vovka and I were friends, I went to his apartment hundreds of times. I liked his dad. He was a good Soviet citizen, modest, a devoted Communist. How could he be a wrecker? I start thinking about it but get nowhere. It's just too confusing. Then I remember what my dad used to say: “There's no smoke without a fire.” If someone is arrested and executed, there must be a good reason for it. The State Security wouldn't be shooting people for nothing. What about my dad, then? He was arrested.

“Sobakin! Zaichik! Get in here!” the principal yells from his office.

I get up, but Vovka doesn't move. I feel bad for him, so I pat him on the shoulder, urging him to join

me. Out of the blue, he leaps up and grabs me by the collar. “I was this close to strangling that teacher scum if not for you. Trying to be a hero like your perfect dad? Too late, dirty wrecker. I'm turning you in.”

me. Out of the blue, he leaps up and grabs me by the collar. “I was this close to strangling that teacher scum if not for you. Trying to be a hero like your perfect dad? Too late, dirty wrecker. I'm turning you in.”

He shoves me aside and strides into the office. In the doorway, he bumps into Nina Petrovna, who is walking out; she shrieks and leaps back. Vovka gives her a nasty grin and goes in. I wait for Nina Petrovna to exit, but she doesn't, glaring at me suspiciously. Sergei Ivanych yells again, “Get in, criminals; I don't have all day.” Nina Petrovna darts out and I go in. Sergei Ivanych orders me to lock the door and stand next to Vovka by the wall.

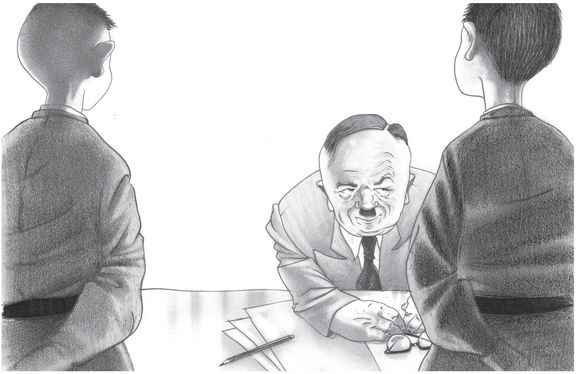

It's bright daylight outside, but his office is dark. All I can see are the large portrait of Stalin and, below, Sergei Ivanych at his desk, eyeing us angrily. “Let me explain what we are looking at,” he says. “I'll make it simple.” He looks at Vovka.

“First you, Sobakin. Thanks to you, I'll have to answer to the appropriate authorities for my weakness of character. No telling what they'll do. I let you stay after your father was put away and I kept it quiet, but what do you do? You attack Nina Petrovna.”

“First you, Sobakin. Thanks to you, I'll have to answer to the appropriate authorities for my weakness of character. No telling what they'll do. I let you stay after your father was put away and I kept it quiet, but what do you do? You attack Nina Petrovna.”

“She's scum,” Vovka says.

“I didn't hear it, Sobakin.” He turns to me. “You, Zaichik. Your father has been arrested and locked up in Lubyanka. You think I don't know?”

I press my back against the wall to keep from falling.

He goes on: “So why not come to me and say, âSergei Ivanych, I want to purify myself from the rotten influence of my father. I want to march with my school to where great Stalin leads.' Huh? You didn't do that, did you?”

I can feel Vovka staring at me, but I won't turn my head.

“Had you done that,” Sergei Ivanych says, “I would have let you denounce your father at today's Pioneers rally. Who knows, maybe we'd even have let you join the Pioneers. But no, you chose to pretend that you are still one of us.”

Here he slams his fist against the desktop so hard, his phone receiver flies off the cradle. “You think you can get away from our State Security? They've been calling all day from the orphanage for the children of the enemies of the people. What was I supposed to tell them, that you're not here?”

Only when Vovka grabs me under my arm do I notice that I'm sliding down to the floor.

“Sobakin,” says Sergei Ivanych, “pull up a chair for Zaichik. The boy needs to sit down.”

I drop into the chair Vovka brings. I guess my dad is not coming to the rally after all. Not coming after all.

Sergei Ivanych sighs, sits back, and looks at us not unkindly. “Boys, boys, you don't know what's good for you,” he says. “Finally, we got rid of that Jew, Finkelstein. That might have satisfied the authorities for a while. But no, you had to get in trouble. I'm sending you both to the orphanage. Case closed.”

“Finkelstein didn't do it,” Vovka says.

“Not my problem. He confessed.” Sergei Ivanych shuffles papers on his desk, then looks up at Vovka. “How do you know he didn't do it?”

“Don't send me to the orphanage and I'll tell you.”

“Don't you blackmail me, Sobakin. You know who broke off the nose?”

“I do,” Vovka says.

Sergei Ivanych smiles. “Here's a chance to correct our failures.” He reaches for the phone. “Operator, get me State Security,” he says into the receiver; then he looks up at me and says, “Think you can make it back to class, Zaichik?”

I nod.

“Run along,” he says. “I'll deal with you later.”

IN THE MAIN HALL, the statue I damaged has been hauled away. It must have been heavy; there are gashes in the floor where they dragged Stalin to the staircase. I wonder where they've taken it. I look around. The hall is deserted, just as it was this morning when I marched in bearing the banner, imagining the May Day parade. It seems like ages ago.

In no hurry to get back to Nina Petrovna's class, I dawdle in the corridor, listening to the sounds coming from behind the closed doors. The classes are in progress. I hear teachers' voices, feet marching to an accordion, chalk knocking against a

blackboard, someone practicing a bugle. Everyone is learning to be useful to our country. Everyone is marching toward Communism, everyone but me. I am no longer a part of the Communist “WE.”

blackboard, someone practicing a bugle. Everyone is learning to be useful to our country. Everyone is marching toward Communism, everyone but me. I am no longer a part of the Communist “WE.”

This is a new feeling, and I don't like it, but it's better not to think about it. This new feeling, I decide, will go away by itself. To distract myself, I peek in on the Russian literature class, not particularly my favorite. The portraits of dead writers line the walls. They all have beards. Luzhko, a substitute teacher, stands at the blackboard. He also has a beard.

“What is the profound meaning of this masterpiece of Russian literature?” he says to the class. “Why is âThe Nose' still so important to us?”

No hands go up, and I'm not surprised. He's talking about a crazy old story they always make us read, called “The Nose.” It's really stupid. Some guy's nose is dressed up in uniformâimagine that!âand it starts putting on airs, as though it's an important government official. It takes place

way before Stalin was our Leader and Teacher, of course. Could something like this happen now? No way. So why should Soviet children read such lies? I don't know. I'm in no hurry, so I keep listening.

way before Stalin was our Leader and Teacher, of course. Could something like this happen now? No way. So why should Soviet children read such lies? I don't know. I'm in no hurry, so I keep listening.

“What âThe Nose' so vividly demonstrates to us today,” says Luzhko, “is that when we blindly believe in someone else's idea of what is right or wrong for us as individuals, sooner or later our refusal to make our own choices could lead to the collapse of the entire political system. An entire country. The world, even.”

He looks at the class significantly and says, “Do you understand?”

Of course, they have no idea what he's talking about. This Luzhko is suspicious. I always thought so. All teachers use words you hear on the radio, but he doesn't. I don't know what's wrong with him. I turn and walk away.

The fact is, Vovka is telling on me right now. By the time I get back to Nina Petrovna's class, everyone will know the truth. Right away they'll start treating me like an enemy of the people. And why shouldn't they? My dad is in prison and it is I, not Finkelstein, who damaged Stalin's statue. I am an enemy of the people and I must face the consequences. “The state will bring him up,” said the senior lieutenant last night when they took my dad away. I didn't understand it then, but I do now. He was talking about the orphanage. Instead of joining the Pioneers, this is where I'm going. They will feed me, clothe me, and put a roof over my head, but nobody will ever trust me again. From this day on, I will be unreliable and suspicious. Me, who loves Stalin more than any of them! It's hard to believe this is really happening, but it is. I don't have to keep thinking any harder to know what I have to do. I'm going to disappear.

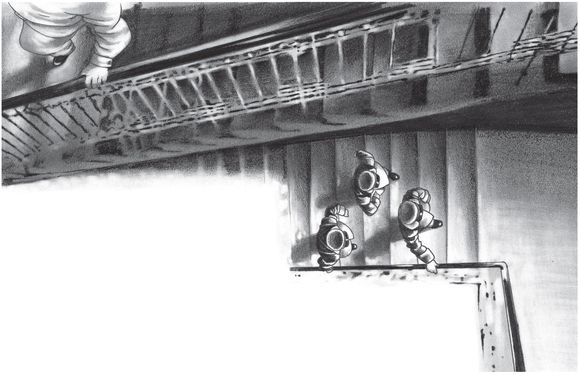

I turn and run back across the main hall, push open the doors to the staircase, and race all the way down. At the bottom of the stairs, I hop over the banister and land right in front of the same senior lieutenant and his two guards.

Other books

Slider by Stacy Borel

Seduced By The General by India T. Norfleet

Major Wyclyff's Campaign (A Lady's Lessons, Book 2) by Lee, Jade

(6/13) Gossip from Thrush Green by Read, Miss

Club Fantasy by Joan Elizabeth Lloyd

Slice of Pi 2 by Elia Winters

Gentleman's Agreement by Hobson, Laura Z.

An Act of Love by Nancy Thayer

Unexpected Love by Melissa Price