Breaking Stalin's Nose (3 page)

Read Breaking Stalin's Nose Online

Authors: Eugene Yelchin

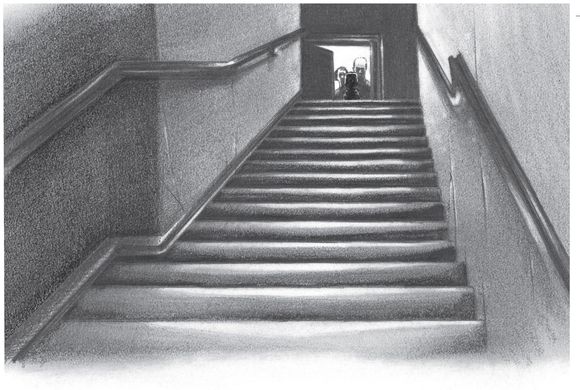

I'M WINDED from running, so I take my time climbing the stairs. What was I thinking? That any fool could just walk into the Kremlin and talk to Stalin? With enemies everywhere and the international situation the way it is? Dad's right: I'm not serious enough. I don't think hard enough.

Aunt Larisa's apartment is on the fifth floor. When I get to her door, I stare at the nameplates under the buzzer; the number nine is scribbled next to her husband's name. I reach for the buzzer but don't touch it. I don't want her sitting up in bed, counting rings, wondering who has come for them

in the middle of the night. I sit down on the step to catch my breath.

in the middle of the night. I sit down on the step to catch my breath.

The door flies open and there's Aunt Larisa, holding a baby wrapped in a blanket. “I knew it,” she whispers. “He's been arrested, right? Arrested?”

I stand up.

The baby starts crying and Aunt Larisa begins rocking it.

“Don't cry, baby. When you grow up, you'll be living in Communism,” I say, and reach in to tickle the baby, but Aunt Larisa pulls it away, frightened. Then her husband is there, leaning out of the door.

“What are you trying to do, kid?” he says. “Get us in trouble?”

“I only need till morning,” I say. “As soon as Stalin finds out, my dad is coming back.”

“Stalin?” he says. He laughs, but it's a nasty laugh.

“It's not funny,” I say. “I will be joining the Pioneers tomorrow and my dad isâ”

“Forget about your dad, kid. Your dad's an enemy of the people. Don't you get it? They don't allow kids of enemies to join the Pioneers.”

My aunt says something, but I can't hear it because the baby is wailing.

“Shush!” her husband hisses, and I'm not sure whom he's hissing at, my aunt or the baby, because both are crying now. He leans forward and drives

his finger into my chest. “Don't aggravate us, kid. Get lost.” And he shuts the door.

his finger into my chest. “Don't aggravate us, kid. Get lost.” And he shuts the door.

I'm almost at the first floor when I hear the door open upstairs. It's my aunt. I stop and wait for her to catch up. I knew she'd come, and she does, arms reaching out and pulling me in. With her face so close, I see she looks like my dad. Though my dad never cries, of course.

“He's wrong,” I say. “My dad's not an enemy of the people. You know that, don't you?”

She nods and pats my head, or tries to arrange my hairâI don't know which. “I'm sorry, Sasha,” she says. “If we take you in, they'll arrest us, too. We just had a baby. We have to stay alive.”

She pushes something into the palm of my hand, folds my fingers over it, and runs upstairs. I know it's money. I'll need it, so I'm grateful. When I look, it's not much, but at least in the morning I can take a streetcar to school.

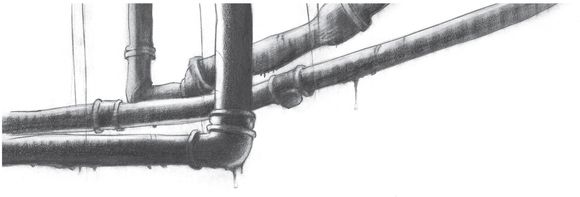

IN THE BASEMENT of my aunt's building, I find a stack of old newspapers. I set aside pages with Stalin's picture on themâdon't want to damage thoseâand make a bed under the warm pipes. It's not so bad in here. The basement is cozy.

I think of the time I last saw Aunt Larisa. It was before she married that jerk. Dad dropped me off and said he would be taking Mom to the hospital because she was ill. I stayed in Aunt Larisa's room for two days. I didn't even go to school. When Dad came back, he said Mom had died at the hospital. I started crying, and Aunt Larisa hugged me and

said to my dad, “You look guilty, not sad.” He didn't say anything, just took me home. There must have been a funeral. I wonder why he didn't take me. I need to ask him about that.

said to my dad, “You look guilty, not sad.” He didn't say anything, just took me home. There must have been a funeral. I wonder why he didn't take me. I need to ask him about that.

The pipes gurgle and hiss above me. In one of the apartments, someone turns on a record player. Normally I only listen to marching music, but this song I like. It's pretty and gentle. Why did Aunt Larisa say my dad looked guilty? He didn't. He looked sad. He blamed himself for not being able to save my mom. He's not even a doctor, but he's that responsible.

I pull the newspapers over my head and start thinking about tomorrow. Tomorrow everything will be better. Tomorrow Stalin will rescue my dad. Tomorrow I will be a Pioneer. I drift off and dream of the Pioneers rally and see my dad, who's smiling and tying the Pioneers scarf around my neck.

THE SOUND of someone scraping ice in the courtyard wakes me. A small window above my head glows bright with winter-morning light.

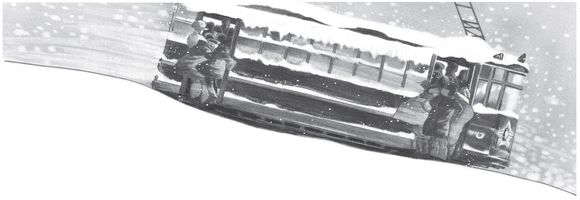

I dash up the stairs, through the front door, and out into the street. The sidewalks are crowded. Citizens rush to work, line up for food rations, push into the streetcars. On the corner, a loudspeaker blares our country's anthem. They always play it at 8:45 sharp, which means I am late for school.

I chase after a streetcar white with frost, icicles hanging over the frozen windows. The streetcar is gaining speed, screeching over icy tracks. I manage to hop on, but the streetcar is so crammed with passengers, I can't squeeze inside. I grab on to the railing and hang outside the doors. The streetcar bounces and darts forward, moving faster and faster, careening down the sloping street. Freezing air lashes my face as Moscow flies by in a whirlwind. After all the bad things that happened last night, this crazy ride is so exciting and fun that I start laughing.

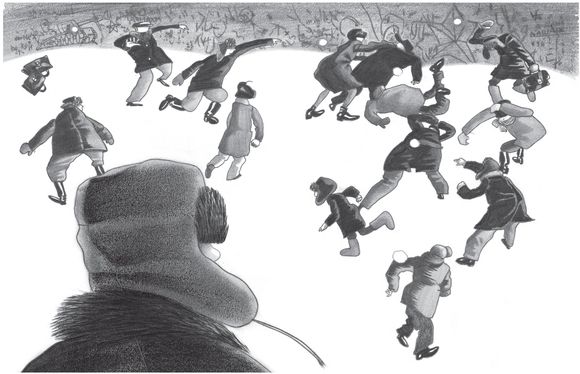

BY THE TIME I get to school, it's snowing again. Everybody's out in the school yard flinging snowballs. I love snowball fights. I have three marksmanship awards from the war-preparedness class, so everyone wants me on their team. I join in. Soon my team is on the offensive, but, of course, Vovka Sobakin has to spoil it. “Watch out,

Amerikanetz

!” he yells, and rams into me so hard, we fly into a snowdrift. He calls me

Amerikanetz

on account of my mother. Vovka used to be my best friend, but I shouldn't have told him anyway. My dad warned me never to tell anyone.

Amerikanetz

!” he yells, and rams into me so hard, we fly into a snowdrift. He calls me

Amerikanetz

on account of my mother. Vovka used to be my best friend, but I shouldn't have told him anyway. My dad warned me never to tell anyone.

“Stop pawing me,” I say to Vovka, push him

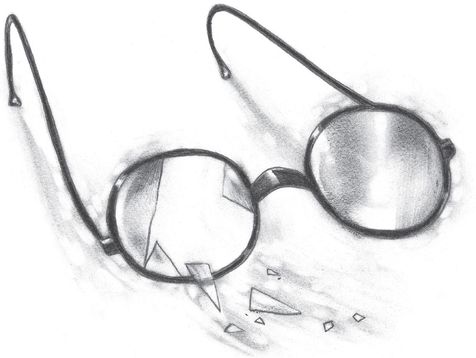

aside, and walk away. When I hear him yell “Death to the enemy of the people!” I freeze. Does he know about my dad? I turn around just as Vovka is lifting a snowball, but he doesn't throw it at me. He throws it at Four-Eyes. Several kids join Vovka and line up into a firing squad. They hurl snowballs at Four-Eyes, who's backed against a wall. He doubles over and covers his face to protect his glasses.

aside, and walk away. When I hear him yell “Death to the enemy of the people!” I freeze. Does he know about my dad? I turn around just as Vovka is lifting a snowball, but he doesn't throw it at me. He throws it at Four-Eyes. Several kids join Vovka and line up into a firing squad. They hurl snowballs at Four-Eyes, who's backed against a wall. He doubles over and covers his face to protect his glasses.

Four-Eyes is Borka Finkelstein, the only Jewish kid in our class. His parents were arrested at the beginning of the year and now he lives with his relatives. We call him Four-Eyes because he wears eyeglasses. Anybody who's not a worker or a peasant and reads a lot, we call Four-Eyes. And it's true; Finkelstein reads a lot.

“Hit him,

Amerikanetz

!” Vovka tries to force the snowball into my hand. The snowball is icy hard and would hurt. I don't feel like throwing it.

Amerikanetz

!” Vovka tries to force the snowball into my hand. The snowball is icy hard and would hurt. I don't feel like throwing it.

“Comrades, look!” Vovka yells. “Zaichik refuses to shoot the enemy!”

“Traitor!” someone shouts. “Enemy of the people!”

“Who's not with us is against us,” Vovka says, grinning, and holds up the snowball. Everyone stares at me, waiting to see what I'll do. That's when Four-Eyes decides to take a chance and throw a snowball. He's nearly blind, so it's a fluke, but it hits me on the ear. Everyone laughs. Before I know what I'm doing, I grab the snowball from Vovka's hand and throw it at Four-Eyes. There's a loud pop as it hits him in the face. The eyeglasses snap, glass splinters, and one shard cuts his cheek.

MY DESK IS FRONT and center, right next to the desk of Nina Petrovna, our classroom teacher. She always seats the best pupils up front. Vovka Sobakin used to sit in my place, but now he's in the back, in Kolyma, with all the bad ones. We call the back row Kolyma because Kolyma is a faraway region in our country where Stalin sends those who don't deserve to live and work among the honest people.

Vovka used to be our model studentâfirst to finish tests, never a grade below an A, helping those lagging behind. Vovka had exceptional penmanship and was also a talented artist. When he won the art

competition, our principal hung Vovka's drawing,

Comrade Stalin at the Helm

, in the main hall. But one day, Vovka snapped. Nobody knows what happened, but he dropped to the bottom of the class academically and started getting reported for bad behavior. Vovka's drawing disappeared from the main hall.

competition, our principal hung Vovka's drawing,

Comrade Stalin at the Helm

, in the main hall. But one day, Vovka snapped. Nobody knows what happened, but he dropped to the bottom of the class academically and started getting reported for bad behavior. Vovka's drawing disappeared from the main hall.

“I have an important announcement, children,” says Nina Petrovna. “The Communist hero, the eagle eyes of our beloved State Security, and the father of your classmate, our dear comrade Zaichik, will be attending the Pioneers rally today and will personally tie the scarves on all of our new Pioneers. Isn't it wonderful?”

I feel everybody's eyes on me, so I sit up the way Nina Petrovna always tells us to: arms folded, back straight, looking up at her. I hope I don't look nervous. The rally is at noon, during the main recess. Will my dad be on time? I don't know. Did someone already tell Stalin? I'm sure someone did;

our State Security is well organized. By now, Stalin must have sent his order: “Free Zaichik immediately!” It's such a simple thing, and Stalin is a brilliant genius of humanity. They always say it on the radio.

our State Security is well organized. By now, Stalin must have sent his order: “Free Zaichik immediately!” It's such a simple thing, and Stalin is a brilliant genius of humanity. They always say it on the radio.

“You'll be joining today, Zaichik,” says Nina Petrovna, smiling her nicest smile at me. “Would you be so kind as to recite for us the Laws of the Young Soviet Pioneers? Children, listen carefully and repeat after Zaichik.”

I stand up. I say, loud and clear, “The Young Pioneer is devoted to Comrade Stalin, the Communist Party, and Communism.”

Just as everyone starts repeating, Nina Petrovna raises her hand for all to stop and says in a stern voice, “Sobakin, what are you doing? Do not repeat after Zaichik. You know perfectly well you're not to be accepted.”

Vovka shrugs. Nina Petrovna smiles at me. “Continue, Zaichik.”

“A Young Pioneer is a reliable comrade and always acts according to conscience.”

“Up, Sobakin!” calls Nina Petrovna. “How dare you repeat the sacred laws after Zaichik? Into the corner, criminal!”

That's the way our Nina Petrovna is. She's nice and fair, but when necessary, she's firm. In my opinion, she's the best teacher in our school.

Vovka slides off his chair and hobbles to the wall, making crazy faces. Everyone laughs.

“Face the wall, Sobakin,” says Nina Petrovna. She turns to me and smiles again, but I see she's angry. Her face is all purple. “I'm sorry, Zaichik. I promise there'll be no more interruptions. Please continue.”

She's keeping her eye on Vovka, ready to correct him, but Vovka's quiet, so I keep going. I've had these laws down since I was six. When I get to “A Young Pioneer has a right to criticize shortcomings,” the door opens and Four-Eyes shuffles in. I should

have had more self-control and stopped myself before I threw that snowball at him. Four-Eyes's glasses are gone and he holds a bloodied kerchief to his cheek. Everyone laughs.

have had more self-control and stopped myself before I threw that snowball at him. Four-Eyes's glasses are gone and he holds a bloodied kerchief to his cheek. Everyone laughs.

“What a pleasant surprise, Finkelstein,” says Nina Petrovna. “A stellar example of another individual who will not be permitted to join the Pioneers.” Then she glares at Vovka and says, “Sobakin's work, no doubt.”

“I didn't do it.”

“Don't expect me to believe you,” snaps Nina Petrovna. “Finkelstein? What happened to you?”

Four-Eyes squints at her and his body starts swaying a little.

“Stop rocking back and forth, Finkelstein. You're not in a synagogue.”

Everyone laughs.

“Speak, Finkelstein.”

He doesn't.

“Pay attention, children. We are learning a

valuable lesson. In our country, even the children of enemies are allowed a choiceâcooperate or face the consequences.”

valuable lesson. In our country, even the children of enemies are allowed a choiceâcooperate or face the consequences.”

She looks at us significantly. “Finkelstein refuses to cooperate with authority, which is me, the teacher. In capitalist countries, the teacher would decide whether to admit Finkelstein back into the classroom or send him to the principal to receive his punishment. But remember, children, the Soviet classroom is the most democratic in the world. You will decide his fate. You will vote. Those in favor of sending Finkelstein to the principal, raise your hands.”

All hands pop up.

Nina Petrovna turns to me and I see that she's surprised. “Are you undecided, Zaichik, or against?”

“He did it. He broke his glasses,” says Vovka into the wall.

Other books

Spider Woman's Daughter by Anne Hillerman

Nina's Dom by Raven McAllan

Legacy of Greyladies by Anna Jacobs

His Illegitimate Heir by Sarah M. Anderson

Secrets over Sweet Tea by Denise Hildreth Jones

Love Me Tender by Audrey Couloumbis

A Siren's Song (Ride of the Darkyrie 2) by Saranna DeWylde

The Bug: Complete Season One by Barry J. Hutchison

The Year Without Summer by William K. Klingaman, Nicholas P. Klingaman

The Bargain by Jane Ashford