Bully for Brontosaurus (39 page)

Read Bully for Brontosaurus Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

Above all, Whiston took delight in his cometary theory because it had resolved this cardinal event in our history as a consequence of nature’s divinely appointed laws, and had thereby removed the need for a special, directly miraculous explanation:

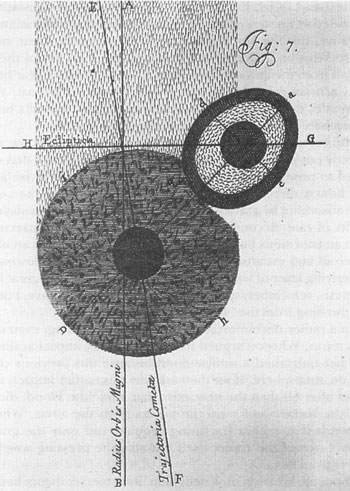

Cometary action as illustrated by Whiston in 1696. A passing comet (large object in the center) induces Noah’s flood. The earth (upper right), entering the comet’s tail, will receive its 40 days and nights of rain. The comet’s gravity is stretching the earth into a spheroid. Under this gravitational tug, the earth’s outer surface will soon crack, releasing water from below (the light, middle layer) to contribute to the deluge.

Whatever difficulties may hitherto have rendered this most noted catastrophe of the old world, that it was destroyed by waters, very hard, if not wholly inexplicable without an Omnipotent Power, and Miraculous Interposition: since the theory of comets, with their atmospheres and tails is discovered, they must vanish of their own accord…. We shall easily see that a deluge of waters is by no means an impossible thing; and in particular that such an individual deluge…which Moses describes, is no more so, but fully accountable that it might be, nay almost demonstrable that it really was.

4.

The coming conflagration

. The prophetic books of Daniel and Revelation speak of a worldwide fire that will destroy the current earth, but in a purifying way that will usher in the millennium. Whiston proposed (as the Laputans feared) that a comet would instigate this conflagration for a set of coordinated reasons. This comet would strip off the earth’s cooling atmosphere, raise the molten material at the earth’s core, and contribute its own fiery heat. Moreover, the passage of this comet would slow the earth’s rotation, thus initiating an orbit so elliptical that the point of closest approach to the sun would be sufficient to ignite our planet’s surface. Thus, Whiston writes, “the theory of comets” can provide “almost as commensurate and complete an account of the future burning, as it already has done of the ancient drowning of the earth.”

5.

The consummation

. As prophecy relates, the thousand-year reign of Christ will terminate with a final battle between the just and the forces of evil led by the giants Gog and Magog. Thereafter, the bodies of the just shall ascend to heaven, those of the damned shall sink in the other direction—and the earth’s appointed role shall be over. This time a comet shall make a direct hit—no more glancing blows for diurnal rotation or near misses for floods—and knock the earth either clear out of the solar system or into an orbit so elliptical that it will become, as it was in the beginning, a comet.

Our conventional, modern reading of Whiston as an impediment to true science arises not only from the fatuous character of this particular reconstruction but also, and primarily, from our recognition that Whiston invoked the laws of nature only to validate a predetermined goal—the rendering of biblical history—and not, as modern ideals proclaim, to chart with objectivity, and without preconception, the workings of the universe. Consider, for example, Whiston’s reverie on how God established the laws of nature so that a comet would instigate a flood just when human wickedness deserved such a calamity.

That Omniscient Being, who foresaw when the degeneracy of human nature would be arrived at an unsufferable degree of wickedness…and when consequently his vengeance ought to fall upon them; predisposed and preadapted the orbits and motions of both the comet and the earth, so that at the very time, and only at that time, the former should pass close by the latter and bring that dreadful punishment upon them.

Yet such an assessment of Whiston seems singularly unfair and anachronistic. How can we justify a judgment of modern taxonomies that didn’t exist in the seventeenth century? We dismiss Whiston because he violated ideals of science as we now define the term. But, in Whiston’s time, science did not exist as a separate domain of inquiry; the word itself had not been coined. No matter how we may view such an enterprise today, Whiston’s mixture of natural events and scriptural traditions defined a primary domain at the forefront of scholarship in his time. We have since defined Whiston’s

New Theory

as a treatise in the history of science because we remain intrigued with his use of astronomical arguments but have largely lost both context for and interest in his exegesis of millennarian prophecy. But Whiston would not have accepted such a categorization; he would not even have recognized our concerns and divisions. He did not view his effort as a work of science, but as a treatise in an important contemporary tradition for using all domains of knowledge—revelations of Scripture, history of ancient chronicles, and knowledge of nature’s laws—to reconstruct the story of human life on our planet. The

New Theory

contains—and by Whiston’s explicit design—far more material on theological principles and biblical exegesis than on anything that would now pass muster as science.

Moreover, although Whiston later achieved a reputation as a crank in his own time, he wrote the

New Theory

at the height of his conventional acceptability. He showed the manuscript to Christopher Wren and won the hearty approval of this greatest among human architects. He then gave (and eventually dedicated) the work to Newton himself, and so impressed Mr. Numero Uno in our current pantheon of scientific heroes that he ended up as Newton’s handpicked successor at Cambridge.

In fact, Whiston’s arguments in the

New Theory

are neither marginal nor oracular, but preeminently Newtonian in both spirit and substance. In reading the

New Theory

, I was particularly struck by a feature of organization, a conceit really, that most commentators pass over. Whiston ordered his book in a manner that strikes us as peculiar (and ultimately quite repetitious). He presents the entire argument as though it could be laid out in a mathematical and logical framework, combining sure knowledge of nature’s laws with clear strictures of a known history in order to deduce the necessity of cometary action as a primary cause.

Whiston begins with the page of

Postulata

, or general principles of explanation cited previously. He then lists eighty-five “lemmata,” or secondary postulates derived directly from laws of nature. The third section discusses eleven “hypotheses”—not “tentative explanations” in the usual, modern sense of the word, but known facts of history assumed beforehand and used as terms in later deductions. Whiston then pretends that he can combine these lemmas and facts to deduce the proper explanation of our planet’s history. The next section lists 101 “phaenomena,” or particular facts that require explanation. The final chapter on “solutions” runs through these facts again to supply cometary (and other) explanations based on the lemmas and hypotheses. (Whiston then ends the book with four pages of “corollaries” extolling God’s power and scriptural authority.)

I call this organization a conceit because it bears the form, but not the substance, of deductive necessity. The lemmas are not an impartial account of consequences from Newton’s laws but a tailored list designed beforehand to yield the desired results. The hypotheses are not historical facts in the usual sense of verified, direct observations but inferences based on a style of biblical exegesis not universally followed even in Whiston’s time. The solutions are not deductive necessities but possible readings that do not include other alternatives (even if one accepts the lemmas and hypotheses).

Still, we must not view Whiston’s

New Theory

as a caricature of Newtonian methodology (if only from the direct evidence that Newton himself greatly admired the book). The Newton of our pantheon is a sanitized and modernized version of the man himself, as abstracted from his own time for the sake of glory, as Whiston has been for the sake of infamy. Newton’s thinking combined the same interests in physics and prophecy, although an almost conspiratorial silence among scholars has, until recently, foreclosed discussion of Newton’s voluminous religious writings, most of which remain unpublished. (James Force’s excellent study,

William Whiston, Honest Newtonian

, 1985, should be consulted on this issue.) Newton and Whiston were soul mates, not master and jester. Whiston’s perceived oddities arose directly from his Newtonian convictions and his attempt to use Newtonian methods (in both scientific and religious argument) to resolve the earth’s history.

I have, over the years, written many essays to defend maligned figures in the traditional history of science. I usually proceed, as I have so far with Whiston, by trying to place an unfairly denigrated man into his own time and to analyze the power and interest of his arguments in their own terms. I have usually held that judgment by modern standards is the pitfall that led to our previous, arrogant dismissal—and that we should suppress our tendency to justify modern interest by current relevance.

Yet I would also hold that old arguments can retain a special meaning and importance for modern scientific debates. Some issues are so broad and general that they transcend all social contexts to emerge as guiding themes in scientific arguments across the centuries (see my book

Time’s Arrow, Time’s Cycle

for such a discussion about metaphors of linear and cyclical time in geology). In these situations, old versions can clarify and instruct our current research because they allow us to tease out the generality from its overlay of modern prejudices and to grasp the guiding power of a primary theme through its application to a past world that we can treat more abstractly, and without personal stake.

Whiston’s basic argument about comets possesses this character of instructive generality. We must acknowledge, first of all, the overt and immediate fact that one of the most exciting items in contemporary science—the theory of mass extinction by extraterrestrial impact—calls upon the same agency (some versions even cite comets as the impacting bodies). Evidence continues to accumulate for the hypothesis that a large extraterrestrial object struck the earth some 65 million years ago and triggered, or at least greatly promoted, the late Cretaceous mass extinction (the sine qua non, of our own existence, since the death of dinosaurs cleared ecological space for the evolution of large mammals). Intensive research is now under way to test the generality of this claim by searching for evidence of similar impacts during other episodes of mass extinction. We await the results with eager anticipation.

But theories of mass extinction do not provide the main reason why we should pay attention to Whiston today. After all, the similarities may be only superficial: Whiston made a conjecture to render millennarian prophecy; the modern theory has mustered some surprising facts to explain an ancient extinction. Guessing right for the wrong reason does not merit scientific immortality. No, I commend Whiston to modern attention for a different and more general cause—because the form and structure of his general argument embody a powerful abstraction that we need to grasp today in our search to understand the roles of stability, gradual change, and catastrophe in the sciences of history.

Whiston turned to comets for an interesting reason rooted in his Newtonian perspective, not capriciously as an easy way out for the salvation of Moses. Scientists who work with the data of history must, above all, develop general theories about how substantial change can occur in a universe governed by invariant natural laws. In Newton’s (and Whiston’s) world view, immanence and stability are the usual consequences of nature’s laws: The cosmos does not age or progress anywhere. Therefore, if substantial changes did occur, they must be rendered by rapid and unusual events that, from time to time, interrupt the ordinary world of stable structure. In other words, Whiston’s catastrophic theory of change arose primarily from his belief in the general stability of nature. Change must be an infrequent fracture or rupture. He wrote:

We know no other natural causes that can produce any great and general changes in our sublunary world, but such bodies as can approach to the earth, or, in other words, but comets.

A major intellectual movement began about a century after Whiston wrote and has persisted to become the dominant ideology of our day. Whiston’s notion of stability as the ordinary state of things yielded to the grand idea that change is intrinsic to the workings of nature. The poet Robert Burns wrote:

Look abroad through nature’s range

Nature’s mighty law is change.

This alternative idea of gradual and progressive change as inherent in nature’s ways marked a major reform in scientific thinking and led to such powerful theories as Lyellian geology and Darwinian evolution. But this notion of slow, intrinsic alteration also established an unfortunate dogma that fostered an amnesia about other legitimate styles of change and often still leads us to restrict our hypotheses to one favored style falsely viewed as preferable (or even true) a priori. For example, the

New York Times

recently suggested that impact theories be disregarded on general principles: