Bully for Brontosaurus (43 page)

Read Bully for Brontosaurus Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

Conflicts develop not because science and religion vie intrinsically, but when one domain tries to usurp the proper space of the other. In that case, a successful defense of home territory is not only noble per se, but a distinct benefit to honorable people in both camps:

The antagonism of science is not to religion, but to the heathen survivals and the bad philosophy under which religion herself is often well-nigh crushed. And, for my part, I trust that this antagonism will never cease, but that to the end of time true science will continue to fulfill one of her most beneficent functions, that of relieving men from the burden of false science which is imposed upon them in the name of religion.

Gladstone responded with a volley of rhetoric. He began from the empyrean heights, pointing out that after so many years of parliamentary life he was a tired (if still grand) old man, and didn’t know if he could muster the energy for this sort of thing anymore—particularly for such a nettlesome and trivial opponent as the merely academic Huxley:

As I have lived for more than half a century in an atmosphere of contention, my stock of controversial fire has perhaps become abnormally low; while Professor Huxley, who has been inhabiting the Elysian regions of science…may be enjoying all the freshness of an unjaded appetite.

(Much of the fun in reading through this debate lies not in the forcefulness of arguments or in the mastery of prose by both combatants, but in the sallying and posturing of two old game-cocks [Huxley was sixty, Gladstone seventy-six in 1885] pulling out every trick from the rhetorical bag—the musty and almost shameful, the tried and true, and even a novel flourish here and there.)

But once Gladstone got going, that old spark fanned quite a flame. His denunciations spanned the gamut. Huxley’s words, on the one hand, were almost too trivial to merit concern—one listens “to his denunciations…as one listens to distant thunders, with a sort of sense that after all they will do no great harm.” On the other hand, Huxley’s attack could not be more dangerous. “I object,” Gladstone writes, “to all these exaggerations…as savoring of the spirit of the Inquisition, and as restraints on literary freedom.”

Yet, when Gladstone got down to business, he could muster only a feeble response to Huxley’s particulars. He did effectively combat Huxley’s one weak argument—the third charge that all groups continue to generate new species, whatever the sequence of their initial appearance. Genesis, Gladstone replies, only discusses the order of origin, not the patterns of subsequent history:

If we arrange the schools of Greek philosophy in numerical order, according to the dates of their inception, we do not mean that one expired before another was founded. If the archaeologist describes to us as successive in time the ages of stone, bronze and iron, he certainly does not mean that no kinds of stone implement were invented after bronze began.

But Gladstone came to grief on his major claim—the veracity of the Genesis sequence: water population, air population, land population, and humans. So he took refuge in the oldest ploy of debate. He made an end run around his disproved argument and changed the terms of discussion. Genesis doesn’t refer to all animals, but “only to the formation of the objects and creatures with which early man was conversant.” Therefore, toss out all invertebrates (although I cannot believe that cockroaches had no foothold, even in the Garden of Eden) and redefine the sequence of water, air, land, and mentality as fish, bird, mammal, and man. At least this sequence matches the geological record. But every attempt at redefinition brings new problems. How can the land population of the sixth day—“every living thing that creepeth upon the earth”—refer to mammals alone and exclude the reptiles that not only arose long before birds but also provided the dinosaurian lineage of their ancestry. This problem backed Gladstone into a corner, and he responded with the weak rejoinder that reptiles are disgusting and degenerate things, destined only for our inattention (despite Eve and the serpent): “Reptiles are a family fallen from greatness; instead of stamping on a great period of life its leading character, they merely skulked upon the earth.” Yet Gladstone sensed his difficulty and admitted that while reptiles didn’t disprove his story, they certainly didn’t help him either: “However this case may be regarded, of course I cannot draw from it any support to my general contention.”

Huxley, smelling victory, moved in for the kill. He derided Gladstone’s slithery argument about reptiles and continued to highlight the evident discrepancies of Genesis, read literally, with geology (“Mr. Gladstone and Genesis,”

The Nineteenth Century

, 1896).

However reprehensible, and indeed contemptible, terrestrial reptiles may be, the only question which appears to me to be relevant to my argument is whether these creatures are or are not comprised under the denomination of “everything that creepeth upon the ground.”

Contrasting the approved tactics of Parliament and science, Huxley obliquely suggested that Gladstone might emulate the wise cobbler and stick to his last. Invoking reptiles once again, he wrote:

Still, the wretched creatures stand there, importunately demanding notice; and, however different may be the practice in that contentious atmosphere with which Mr. Gladstone expresses and laments his familiarity, in the atmosphere of science it really is of no avail whatever to shut one’s eyes to facts, or to try to bury them out of sight under a tumulus of rhetoric.

Gladstone’s new sequence of fish, bird, mammal, and man performs no better than his first attempt in reconciling Genesis and geology. The entire enterprise, Huxley asserts, is misguided, wrong, and useless: “Natural science appears to me to decline to have anything to do with either [of Gladstone’s two sequences]; they are as wrong in detail as they are mistaken in principle.” Genesis is a great work of literature and morality, not a treatise on natural history:

The Pentateuchal story of the creation is simply a myth [in the literary, not pejorative, sense of the term]. I suppose it to be a hypothesis respecting the origin of the universe which some ancient thinker found himself able to reconcile with his knowledge, or what he thought was knowledge, of the nature of things, and therefore assumed to be true. As such, I hold it to be not merely an interesting but a venerable monument of a stage in the mental progress of mankind.

Gladstone, who was soon to enjoy a fourth stint as prime minister, did not respond. The controversy then flickered, shifting from the pages of

The Nineteenth Century

to the letters column of the

Times

. Then it died for a while, only to be reborn from time to time ever since.

I find something enormously ironical in this old battle, fought by Huxley and Gladstone a century ago and by much lesser lights even today. It doesn’t matter a damn because Huxley was right in asserting that correspondence between Genesis and the fossil record holds no significance for religion or for science. Still, I think that Gladstone and most modern purveyors of his argument have missed the essence of the kind of myth that Genesis 1 represents. Nothing could possibly be more vain or intemperate than a trip on these waters by someone lacking even a rudder or a paddle in any domain of appropriate expertise. Still, I do feel that when read simply for its underlying metaphor, the story of Genesis 1 does contradict Gladstone’s fundamental premise. Gladstone’s effort rests upon the notion that Genesis 1 is a tale about

addition

and linear sequence—God makes this, then this, and then this in a sensible order. Since Gladstone also views evolution and geology as a similar story of progress by accretion, reconciliation becomes possible. Gladstone is quite explicit about this form of story:

Evolution is, to me, a series with development. And like series in mathematics, whether arithmetical or geometrical, it establishes in things an unbroken progression; it places each thing…in a distinct relation to every other thing, and makes each a witness to all that have preceded it, a prophecy of all that are to follow it.

But I can’t read Genesis 1 as a story about linear addition at all. I think that its essential theme rests upon a different metaphor

—differentiation

rather than accretion. God creates a chaotic and formless

totality

at first, and then proceeds to make divisions within—to precipitate islands of stability and growing complexity from the vast, encompassing potential of an initial state. Consider the sequence of “days.”

On day one, God makes two primary and orthogonal divisions: He separates heaven from earth, and light from darkness. But each category only represents a diffuse potential, containing no differentiated complexity. The earth is “without form and void” and no sun, moon, or stars yet concentrate the division of light from darkness. On the second day, God consolidates the separation of heaven and earth by creating the firmament and calling it heaven. The third day is then devoted to differentiating the chaotic earth into its stable parts—land and sea. Land then develops further by bringing forth plants. (Does this indicate that the writer of Genesis treated life under a taxonomy very different from ours? Did he see plants as essentially of the earth and animals as something separate? Would he have held that plants have closer affinity with soil than with animals?) The fourth day does for the firmament what the third day accomplished for earth: heaven differentiates and light becomes concentrated into two great bodies, the sun and moon.

The fifth and sixth days are devoted to the creation of animal life, but again the intended metaphor may be differentiation rather than linear addition. On the fifth day, the sea and then the air bring forth their intended complexity of living forms. On the sixth day, the land follows suit. The animals are not simply placed by God in their proper places. Rather, the places themselves “bring forth” or differentiate their appropriate inhabitants at the appointed times.

The final result is a candy box of intricately sculpted pieces, with varying degrees of complexity. But how did the box arise? Did the candy maker just add items piece by piece, according to a prefigured plan—Gladstone’s model of linear addition? Or did he start with the equivalent of a tray of fudge, and then make smaller and smaller divisions with his knife, decorating each piece as he cut by sculpting wondrous forms from the potential inherent in the original material? I read the story in this second manner. And if differentiation be the more appropriate metaphor, then Genesis cannot be matching Gladstone’s linear view of evolution. The two stories rest on different premises of organization—addition and differentiation.

*

But does life’s history really match either of these two stories? Addition and differentiation are not mutually exclusive truths inherent in nature. They are schemata of organization for human thought, two among a strictly limited number of ways that we have devised to tell stories about nature’s patterns. Battles have been fought in their names many times before, sometimes strictly within biology. Consider, for example, the early nineteenth century struggle in German embryology between one of the greatest of all natural scientists, Karl Ernst von Baer, who viewed development as a process of differentiation from general forms to specific structures, and the

Naturphilosophen

(nature philosophers) with their romantic conviction that all developmental processes (including embryology) must proceed by linear addition of complexity as spirit struggles to incarnate itself in the highest, human form (see Chapter 2 of my book

Ontogeny and Phylogeny

, Harvard University Press, 1977).

My conclusion may sound unexciting, even wishy-washy, but I think that evolution just says yes to both metaphors for different parts of its full complexity. Yes, truly novel structures do arise in temporal order—first fins, then legs, then hair, then language—and additive models describe part of the story well. Yes, the coding rules of DNA have not changed, and all of life’s history differentiates from a potential inherent from the first. Is the history of Western song a linear progression of styles or the construction of more and more castles for a kingdom fully specified in original blueprints by notes of the scale and rules of composition?

Finally, and most important, the bankruptcy of Gladstone’s effort lies best exposed in this strictly limited number of deep metaphors available to our understanding. Gladstone was wrong in critical detail, as Huxley so gleefully proved. But what if he had been entirely right? What if the Genesis sequence had been generally accurate in its broad brush? Would such a correspondence mean that God had dictated the Torah word by word? Of course not. How many possible stories can we tell? How many can we devise beyond addition and differentiation? Simultaneous creation? Top down appearance? Some, perhaps, but not many. So what if the Genesis scribe wrote his beautiful myth in one of the few conceivable and sensible ways—and if later scientific discoveries then established some fortuitous correspondences with his tale? Bats didn’t know about extinct pterodactyls, but they still evolved wings that work in similar ways. The strictures of flying don’t permit many other designs—just as the limited pathways from something small and simple to something big and complex don’t allow many alternatives in underlying metaphor. Genesis and geology happen not to correspond very well. But it wouldn’t mean much if they did—for we would only learn something about the limits to our storytelling, not even the whisper of a lesson about the nature and meaning of life or God.

Genesis and geology are sublimely different. William Jennings Bryan used to dismiss geology by arguing that he was only interested in the rock of ages, not the age of rocks. But in our tough world—not cleft for us, and offering no comfortable place to hide—I think we had better pay mighty close attention to both.

I HAVE SEVERAL REASONS

for choosing to celebrate our legal victory over “creation science” by trying to understand with sympathy the man who forged this long and painful episode in American history—William Jennings Bryan. In June 1987, the Supreme Court voided the last creationist statute by a decisive 7–2 vote, and then wrote their decision in a manner so clear, so strong, and so general that even the most ardent fundamentalists must admit the defeat of their legislative strategy against evolution. In so doing, the Court ended William Jennings Bryan’s last campaign, the cause that he began just after World War I as his final legacy, and the battle that took both his glory and his life in Dayton, Tennessee, when, humiliated by Clarence Darrow, he died just a few days after the Scopes trial in 1925.

My reasons range across the domain of Bryan’s own character. I could invoke rhetorical and epigrammatic expressions, the kind that Bryan, as America’s greatest orator, laced so abundantly into his speeches—Churchill’s motto for World War II, for example: “In victory: magnanimity.” But I know that my main reason is personal, even folksy, the kind of one-to-one motivation that Bryan, in his persona as the Great Commoner, would have applauded. Two years ago, a colleague sent me an ancient tape of Bryan’s voice. I expected to hear the pious and polished shoutings of an old stump master, all snake oil and orotund sophistry. Instead, I heard the most uncanny and friendly sweetness, high pitched, direct, and apparently sincere. Surely this man could not simply be dismissed, as by H. L. Mencken, reporting the Scopes trial for the Baltimore

Sun:

as “a tinpot Pope in the Coca-Cola belt.”

I wanted to understand a man who could speak with such warmth, yet talk such yahoo nonsense about evolution. I wanted, above all, to resolve a paradox that has always cried out for some answer rooted in Bryan’s psyche. How could this man, America’s greatest populist reformer, become, late in life, her arch reactionary?

For it was Bryan who, just one year beyond the minimum age of thirty-five, won the Democratic presidential nomination in 1896 with his populist rallying cry for abolition of the gold standard: “You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns. You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.” Bryan who ran twice more, and lost in noble campaigns for reform, particularly for Philippine independence and against American imperialism. Bryan, the pacifist who resigned as Wilson’s secretary of state because he sought a more rigid neutrality in the First World War. Bryan who stood at the forefront of most progressive victories in his time: women’s suffrage, the direct election of senators, the graduated income tax (no one loves it, but can you think of a fairer way?). How could this man have then joined forces with the cult of biblical literalism in an effort to purge religion of all liberality, and to stifle the same free thought that he had advocated in so many other contexts?

This paradox still intrudes upon us because Bryan forged a living legacy, not merely an issue for the mists and niceties of history. For without Bryan, there never would have been anti-evolution laws, never a Scopes trial, never a resurgence in our day, never a decade of frustration and essays for yours truly, never a Supreme Court decision to end the issue. Every one of Bryan’s progressive triumphs would have occurred without him. He fought mightily and helped powerfully, but women would be voting today and we would be paying income tax if he had never been born. But the legislative attempt to curb evolution was his baby, and he pursued it with all his legendary demoniac fury. No one else in the ill-organized fundamentalist movement had the inclination, and surely no one else had the legal skill or political clout. Ironically, fundamentalist legislation against evolution is the only truly distinctive and enduring brand that Bryan placed upon American history. It was Bryan’s movement that finally bit the dust in Washington in June of 1987.

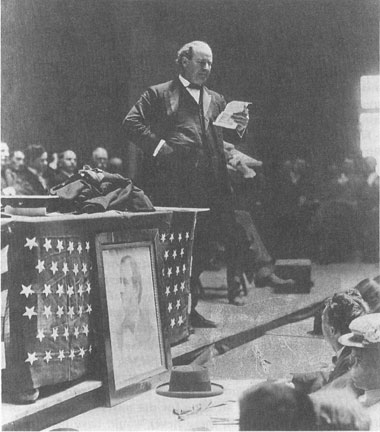

William Jennings Bryan on the stump. Taken during the presidential campaign of 1896.

THE BETTMANN ARCHIVE

.

The paradox of shifting allegiance is a recurring theme in literature about Bryan. His biography in the

Encyclopaedia Britannica

holds that the Scopes trial “proved to be inconsistent with many progressive causes he had championed for so long.” One prominent biographer located his own motivation in trying to discover “what had transformed Bryan from a crusader for social and economic reform to a champion of anachronistic rural evangelism, cheap moral panaceas, and Florida real estate” (L. W. Levine, 1965).

Two major resolutions have been proposed. The first, clearly the majority view, holds that Bryan’s last battle was inconsistent with, even a nullification of, all the populist campaigning that had gone before. Who ever said that a man must maintain an unchanging ideology throughout adulthood; and what tale of human psychology could be more familiar than the transition from crusading firebrand to diehard reactionary. Most biographies treat the Scopes trial as an inconsistent embarrassment, a sad and unsettling end. The title to the last chapter of almost every book about Bryan features the word “retreat” or “decline.”

The minority view, gaining ground in recent biographies and clearly correct in my judgment, holds that Bryan never transformed or retreated, and that he viewed his last battle against evolution as an extension of the populist thinking that had inspired his life’s work (in addition to Levine, cited previously, see Paolo E. Coletta, 1969, and W. H. Smith, 1975).

Bryan always insisted that his campaign against evolution meshed with his other struggles. I believe that we should take him at his word. He once told a cartoonist how to depict the harmony of his life’s work: “If you would be entirely accurate you should represent me as using a double-barreled shotgun, firing one barrel at the elephant as he tries to enter the treasury and another at Darwinism—the monkey—as he tries to enter the schoolroom.” And he said to the Presbyterian General Assembly in 1923: “There has not been a reform for 25 years that I did not support. And I am now engaged in the biggest reform of my life. I am trying to save the Christian Church from those who are trying to destroy her faith.”

But how can a move to ban the teaching of evolution in public schools be deemed progressive? How did Bryan link his previous efforts to this new strategy? The answers lie in the history of Bryan’s changing attitudes toward evolution.

Bryan had passed through a period of skepticism in college. (According to one story, more than slightly embroidered no doubt, he wrote to Robert G. Ingersoll for ammunition but, upon receiving only a pat reply from his secretary, reverted immediately to orthodoxy.) Still, though Bryan never supported evolution, he did not place opposition high on his agenda; in fact, he evinced a positive generosity and pluralism toward Darwin. In “The Prince of Peace,” a speech that ranked second only to the “Cross of Gold” for popularity and frequency of repetition, Bryan said:

I do not carry the doctrine of evolution as far as some do; I am not yet convinced that man is a lineal descendant of the lower animals. I do not mean to find fault with you if you want to accept the theory…. While I do not accept the Darwinian theory I shall not quarrel with you about it.

(Bryan, who certainly got around, first delivered this speech in 1904, and described it in his collected writings as “a lecture delivered at many Chautauqua and religious gatherings in America, also in Canada, Mexico, Tokyo, Manila, Bombay, Cairo, and Jerusalem.”)

He persisted in this attitude of laissez-faire until World War I, when a series of events and conclusions prompted his transition from toleration to a burning zeal for expurgation. His arguments did not form a logical sequence, and were dead wrong in key particulars; but who can doubt the passion of his feelings?

We must acknowledge, before explicating the reasons for his shift, that Bryan was no intellectual. Please don’t misconstrue this statement. I am not trying to snipe from the depth of Harvard elitism, but to understand. Bryan’s dearest friends said as much. Bryan used his first-rate mind in ways that are intensely puzzling to trained scholars—and we cannot grasp his reasons without mentioning this point. The “Prince of Peace” displays a profound ignorance in places, as when Bryan defended the idea of miracles by stating that we continually break the law of gravity: “Do we not suspend or overcome the law of gravitation every day? Every time we move a foot or lift a weight we temporarily overcome one of the most universal of natural laws and yet the world is not disturbed.” (Since Bryan gave this address hundreds of times, I assume that people tried to explain to him the difference between laws and events, or reminded him that without gravity, our raised foot would go off into space. I must conclude that he didn’t care because the line conveyed a certain rhetorical oomph.) He also explicitly defended the suppression of understanding in the service of moral good:

If you ask me if I understand everything in the Bible, I answer no, but if we will try to live up to what we do understand, we will be kept so busy doing good that we will not have time to worry about the passages which we do not understand.

This attitude continually puzzled his friends and provided fodder for his enemies. One detractor wrote: “By much talking and little thinking his mentality ran dry.” To the same effect, but with kindness, a friend and supporter wrote that Bryan was “almost unable to think in the sense in which you and I use that word. Vague ideas floated through his mind but did not unite to form any system or crystallize into a definite practical position.”

Bryan’s long-standing approach to evolution rested upon a threefold error. First, he made the common mistake of confusing the fact of evolution with the Darwinian explanation of its mechanism. He then misinterpreted natural selection as a martial theory of survival by battle and destruction of enemies. Finally, he made the logical error of arguing that Darwinism implied the moral virtuousness of such deathly struggle. He wrote in the

Prince of Peace

(1904):

The Darwinian theory represents man as reaching his present perfection by the operation of the law of hate—the merciless law by which the strong crowd out and kill off the weak. If this is the law of our development then, if there is any logic that can bind the human mind, we shall turn backward toward the beast in proportion as we substitute the law of love. I prefer to believe that love rather than hatred is the law of development.

And to the sociologist E. A. Ross, he said in 1906 that “such a conception of man’s origin would weaken the cause of democracy and strengthen class pride and the power of wealth.” He persisted in this uneasiness until World War I, when two events galvanized him into frenzied action. First, he learned that the martial view of Darwinism had been invoked by most German intellectuals and military leaders as a justification for war and future domination. Second, he feared the growth of skepticism at home, particularly as a source of possible moral weakness in the face of German militarism.

Bryan united his previous doubts with these new fears into a campaign against evolution in the classroom. We may question the quality of his argument, but we cannot deny that he rooted his own justifications in his lifelong zeal for progressive causes. In this crucial sense, his last hurrah does not nullify, but rather continues, all the applause that came before. Consider the three principal foci of his campaign, and their links to his populist past:

1. For peace and compassion against militarism and murder. “I learned,” Bryan wrote, “that it was Darwinism that was at the basis of that damnable doctrine that might makes right that had spread over Germany.”

2. For fairness and justice toward farmers and workers and against exploitation for monopoly and profit. Darwinism, Bryan argued, had convinced so many entrepreneurs about the virtue of personal gain that government now had to protect the weak and poor from an explosion of anti-Christian moral decay: “In the United States,” he wrote,

pure-food laws have become necessary to keep manufacturers from poisoning their customers; child labor laws have become necessary to keep employers from dwarfing the bodies, minds and souls of children; anti-trust laws have become necessary to keep overgrown corporations from strangling smaller competitors, and we are still in a death grapple with profiteers and gamblers in farm products.

3. For absolute rule of majority opinion against imposing elites. Christian belief still enjoyed widespread majority support in America, but college education was eroding a consensus that once ensured compassion within democracy. Bryan cited studies showing that only 15 percent of college male freshmen harbored doubts about God, but that 40 percent of graduates had become skeptics. Darwinism, and its immoral principle of domination by a selfish elite, had fueled this skepticism. Bryan railed against this insidious undermining of morality by a minority of intellectuals, and he vowed to fight fire with fire. If they worked through the classroom, he would respond in kind and ban their doctrine from the public schools. The majority of Americans did not accept human evolution, and had a democratic right to proscribe its teaching.