Caesar's Messiah: The Roman Conspiracy to Invent Jesus:Flavian Signature Edition (2 page)

Read Caesar's Messiah: The Roman Conspiracy to Invent Jesus:Flavian Signature Edition Online

Authors: Joseph Atwill

In the midst of the Judean war, forces loyal to the Flavian family in Rome revolted against the last of the Julio-Claudian emperors, Vitellius, and seized the capital. Vespasian returned to Rome to be proclaimed emperor, leaving his son Titus in Judea to finish off the rebels.

Following the war, the Flavians shared control over this region between Egypt and Syria with two families of powerful Hellenized Jews: the Herods and the Alexanders. These three families shared a common financial interest in preventing any future revolts. They also shared a long-standing and intricate personal relationship that can be traced to the household of Antonia, the mother of the Emperor Claudius. Antonia employed Julius Alexander Lysimachus, the Abalarch, or ruler, of the Jews of Alexandria, as her financial steward in around 45 C.E.

Julius was the elder brother of the famous Jewish philosopher Philo Judeaus, the leading intellectual figure of Hellenistic Judaism. Philo’s writings attempted to merge Judaism with Platonic philosophy. Scholars believe that his work provided the authors of the Gospels with some of their religious and philosophical perspective.

Antonia’s private secretary, Caenis, was also the long-term mistress of Vespasian. Julius Alexander Lysimachus and Vespasian would therefore have known one another through their shared connection with the household of Antonia.

Julius had two sons. The elder, Marcus, married Herod’s niece Bernice as a teenager, creating a bond between the Alexanders and the Herods, the Roman-sponsored ruling family of Judea. Marcus died young and Bernice eventually became the mistress of Vespasian’s son Titus. Bernice thereby connected the Flavians and the Alexanders, the family of her first husband, to her family, the Herods.

Julius’ younger son, Tiberius Alexander, was another important link between the families. He inherited his father’s entire estate after the death of his brother Marcus, making him one of the richest men in the world. He renounced Judaism and assisted the Flavians with their war against the Jews, contributing both money and troops, as did the Herodian family. Tiberius was the first to publicly declare his allegiance to Vespasian as emperor and thereby helped begin the Flavian dynasty. When Vespasian returned to Rome to assume the mantle of emperor, he left Tiberius behind to assist his son Titus with the destruction of Jerusalem.

Though the three families had been able to put down the revolt, they still faced a potential threat. Many Jews continued to believe that God would send a Messiah, a son of David, who would lead them against the enemies of Judea. Flavius Josephus records that what had “most elevated” the Sicarii to fight against Rome was their belief that God would send a Messiah to Israel who would lead his faithful to military victory. Though the Flavians, Herods, and Alexanders had ended the Jewish revolt, the families had not destroyed the messianic religion of the Jewish rebels. The families needed to find a way to prevent the Zealots from inspiring future uprisings through their belief in a coming warrior Messiah.

Then someone from within this circle had an inspiration, one that changed history. The way to tame messianic Judaism would be to simply transform it into a religion that would cooperate with the Roman Empire. To achieve this goal would require a new type of messianic literature. Thus, what we know as the Christian Gospels were created.

In a convergence unique in history, the Flavians, Herods, and Alexanders brought together the elements necessary for the creation and implementation of Christianity. They had the financial motivation to replace the militaristic religion of the Sicarii, the expertise in Judaism and philosophy necessary to create the Gospels, and the knowledge and bureaucracy required to implement a religion (the Flavians created and maintained a number of religions other than Christianity). Moreover, these families were the absolute rulers over the territories where the first Christian congregations began.

To produce the Gospels required a deep understanding of Judaic literature. The Gospels would not simply replace the literature of the old religion, but would be written in such a way as to demonstrate that Christianity was the fulfillment of the prophecies of Judaism and had therefore grown directly from it. To achieve these effects, the Flavian intellectuals made use of a technique used throughout Judaic literature—typology. The genre of typology is not often used today. In its most basic sense, typology is simply the use of prior events to provide form and context for subsequent ones – similar to using an archetype or stereotype to create a new character in literature. The typology in the Gospels is very specific – the system uses repeating names, locations, or concepts in the same sequence.

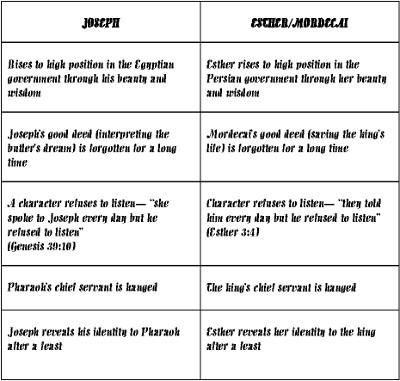

Typology is used throughout Judaic literature as a way of transferring information and meaning from one story to another, to show the pattern of the “hand of God” at work. For example, the Book of Esther uses type scenes from the story of Joseph in the Book of Genesis, so that the alert reader will understand that Esther and Mordecai are repeating the role of Joseph as an agent of God.

The authors of the Gospels used typology to create the impression that events from the lives of prior Hebrew prophets were types of events from Jesus’ life. In doing so, they were trying to convince their readers that their story of Jesus was a continuation of the divine relationship that existed between the Hebrew prophets and God.

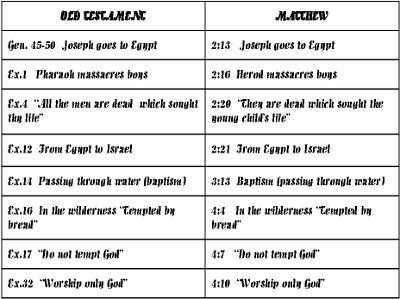

At the very beginning of the Gospels, the authors created a crystal-clear typological relationship between Jesus and Moses. The authors placed this sequence at the beginning of their work to show the reader how the real meaning of the New Testament will be revealed.

The sequence begins in Matthew 2:13, where Joseph is described as bringing Jesus, who represents the “new Israel,” down to Egypt. This event parallels Genesis 45–50, where a previous Joseph brought the “old Israel” down to Egypt.

The authors of the Gospels associated their Joseph with the prior one by means of more than just a shared name and a journey to Egypt. The New Testament Joseph is described, like his counterpart in the Hebrew Bible, as a dreamer of dreams and as having encounters with a star and wise men.

Both stories regarding the journey of a Joseph to Egypt are immediately followed by a description of a massacre of innocents. The stories concerning the massacre of innocents are not exactly parallel. Jesus is not, for example, saved by being put in a boat on the river Jordan and then by being adopted by Herod’s daughter. The typology used within Judaic literature does not require verbatim quotations or descriptions; rather, the author takes only enough information from the event that is being used as the type to allow the reader to recognize that the prior event relates to the one being described. In this case, each massacre of the innocents’ story depicts young children being slaughtered by a fearful tyrant, but the future savior of Israel being saved.

The authors of the New Testament then continue mirroring Exodus by having an angel tell Joseph, “They are dead which sought the young child’s life” (Matt. 2:20). This statement is a clear parallel to the statement made to Moses, the first savior of Israel, in Exodus 4:19: “All the men are dead which sought thy life.” The parallels then continue with Jesus receiving a baptism (Matt. 3:13), which mirrors the baptism of the Israelites (passing through water) described in Exodus 14. Next, Jesus spends 40 days in the desert, which parallels the 40 years the Israelites spend in the wilderness. Both sojourns in the desert involve three sets of temptations. In Exodus, it is God who is tempted; in the Gospels, it is Jesus, the son of God.

In Exodus, it is the Israelites who tempt God. They first tempt him by asking for bread, at which time they learn that “man does not live by bread alone” (Ex. 16). The second time is at Massah, where they are told to not “tempt the Lord” (Ex. 17). On the third occasion, when they make the golden calf at Mount Sinai (Ex. 32), they learn to “fear the Lord thy God and serve only him.”

Jesus’ three temptations are by the devil and are a mirror of God’s temptations by the Israelites, as his responses show. To his first temptation (Matt. 4:4) he replies, “Man shall not live by bread alone.” To the second (Matt. 4:7) he replies, “Thou shalt not tempt the Lord thy God.” And to the third (Matt. 4:10) he replies, “Thou shalt worship the Lord thy God, and only him shalt thou serve.”

Though the parallels between Jesus and Moses are typological and not verbatim, the sequence in which these events occur is. The fact that the parallel concepts occur in the same order is proof that Moses, the first savior of Israel, was used as a type for Jesus, the second savior of Israel.

The typological sequence in Matthew that establishes Jesus as the new savior of Israel is well known to scholars.

1

What has not been widely recognized is that the story also reveals the political perspective of the authors of the New Testament. In the Hebrew Bible it is the Israelites who tempt God, but notice that the devil takes their place in the parallel New Testament story. This equating of the Israelites with the devil is consistent with what the Flavians thought of the messianic Jews, that they were demons.

Moreover, the parallel sequences demonstrate that the Gospels were designed to be read intertextually, that is, in direct relationship to the other books of the Bible. This is the only way that literature based on types can be understood. In other words, as the example concerning Jesus’ infancy illustrates, to understand the Gospels’ meaning a reader must recognize that the concepts, sequences, and locations in Matthew are parallel to the concepts, sequences, and locations in Genesis and Exodus, where their context has already been established.

By using scenes from Judaic literature as types for events in Jesus’ ministry, the authors hoped to convince their readers that the Gospels were a continuation of the Hebrew literature that had inspired the Sicarii to revolt and that, therefore, Jesus was the Messiah whom the rebels were hoping God would send them. In this way, they would strip messianic Judaism of its power to spawn insurrections, since the Messiah was no longer coming but had already come. Further, the Messiah was not the xenophobic military leader that the Sicarii were expecting, but rather a multiculturist who urged his followers to “turn the other cheek.”

If the Gospels achieved only the replacement of the militaristic messianic movement with a pacifistic one, they would have been one of the most successful pieces of propaganda in history. But the authors wanted even more. They wanted not merely to pacify the religious warriors of Judea but to make them worship Caesar as a god. And they wanted to inform posterity that they had done so.

The populations of the Roman provinces were permitted to worship in any way they wished, with one exception; they had to allow Caesar to be worshiped in their temples. This was incompatible with monotheistic Judaism. At the end of the 66–73 C.E. war, Flavius Josephus recorded that no matter how Titus tortured the Sicarii, they refused to call him “Lord.” To circumvent the Jews’ religious stubbornness, the Flavians therefore created a religion that worshiped Caesar without its followers knowing it.

To achieve this, they used the same typological method they had used to link Jesus to Moses, creating parallel concepts, sequences, and locations. They created Jesus’ entire ministry as a “type” of the military campaign of Titus. In other words, events from Jesus’ ministry are symbolic representations of events from Titus’ campaign. To prove that these typological scenes were not accidental, the authors placed them in the same sequence and in the same locations in the Gospels as they had occurred in Titus’ campaign.

The parallel scenes were designed to create another story line than the one that appears on the surface. This typological story line reveals that the Jesus who interacted with the disciples following the crucifixion, the actual Jesus that Christians have unwittingly worshiped for 2,000 years, was Titus Flavius.

The discovery of the Flavian invention of Christianity creates a new understanding of the entire first century C.E. Such a revelation is disorienting, and the reader will find the following points useful in understanding the new history that this work presents.