Caesar's Messiah: The Roman Conspiracy to Invent Jesus:Flavian Signature Edition (44 page)

Read Caesar's Messiah: The Roman Conspiracy to Invent Jesus:Flavian Signature Edition Online

Authors: Joseph Atwill

BOOK 7, CHAPTER 11 - CONCERNING JONATHAN, ONE OF THE SICARII, THAT STIRRED UP A SEDITION IN CYRENE, AND WAS A FALSE ACCUSER [OF THE INNOCENT].

AND now did the madness of the Sicarii, like a disease, reach as far as the cities of Cyrene;

for one Jonathan, a vile person, and by trade a weaver, came thither and prevailed with no small number of the poorer sort to give ear to him; he also led them into the desert, upon promising them that he would show them signs and apparitions.

And as for the other Jews of Cyrene, he concealed his knavery from them, and put tricks upon them; but those of the greatest dignity among them informed Catullus, the governor of the Libyan Pentapolis, of his march into the desert, and of the preparations he had made for it.

So he sent out after him both horsemen and footmen, and easily overcame them, because they were unarmed men; of these many were slain in the fight, but some were taken alive, and brought to Catullus.

As for Jonathan, the head of this plot, he fled away at that time; but upon a great and very diligent search, which was made all the country over for him, he was at last taken. And when he was brought to Catullus, he devised a way whereby he both escaped punishment himself, and afforded an occasion to Catullus of doing much mischief;

for he falsely accused the richest men among the Jews, and said that they had put him upon what he did.

Now Catullus easily admitted of these his calumnies, and aggravated matters greatly, and made tragical exclamations, that he might also be supposed to have had a hand in the finishing of the Jewish war.

But what was still harder, he did not only give a too easy belief to his stories, but he taught the Sicarii to accuse men falsely.

He bid this Jonathan, therefore, to name one Alexander, a Jew (with whom he had formerly had a quarrel, and openly professed that he hated him); he also got him to name his wife Bernice, as concerned with him. These two Catullus ordered to be slain in the first place; nay, after them he caused all the rich and wealthy Jews to be slain, being no fewer in all than three thousand.

This he thought he might do safely, because he confiscated their effects, and added them to Caesar’s revenues.

Nay, indeed, lest any Jews that lived elsewhere should convict him of his villainy, he extended his false accusations further, and persuaded Jonathan, and certain others that were caught with him, to bring an accusation of attempts for innovation against the Jews that were of the best character both at Alexandria and at Rome.

One of these, against whom this treacherous accusation was laid, was Josephus, the writer of these books.

However, this plot, thus contrived by Catullus, did not succeed according to his hopes; for though he came himself to Rome, and brought Jonathan and his companions along with him in bonds, and thought he should have had no further inquisition made as to those lies that were forged under his government, or by his means;

yet did Vespasian suspect the matter and made an inquiry how far it was true. And when he understood that the accusation laid against the Jews was an unjust one, he cleared them of the crimes charged upon them, and this on account of Titus’ concern about the matter, and brought a deserved punishment upon Jonathan; for he was first tormented, and then burnt alive.

But as to Catullus, the emperors were so gentle to him, that he underwent no severe condemnation at this time; yet was it not long before he fell into a complicated and almost incurable distemper, and died miserably. He was not only afflicted in body, but the distemper in his mind was more heavy upon him than the other;

for he was terribly disturbed, and continually cried out that he saw the ghosts of those whom he had slain standing before him. Whereupon he was not able to contain himself, but leaped out of his bed, as if both torments and fire were brought to him.

Thus his distemper grew still a great deal worse and worse continually, and his very entrails were so corroded, that they fell out of his body, and in that condition he died. Thus he became as great an instance of Divine Providence as ever was, and demonstrated that God punishes wicked men.

143

The passage creates a puzzle that uses the name-switching technique found in the Decius Mundus puzzle (which will be analyzed in the next chapter) to identify the creators of Christianity. They are the individuals who were falsely accused by Catullus—Josephus, Bernice, and Alexander. The inventors of Christianity have signed their work, so to speak, in the correct place—at the end of their story.

I believe that the “Bernice” and the “Alexander” in the passage are easily identified as Titus’ mistress Bernice, and either Marcus Alexander, who actually was Bernice’s husband but who died before the Jewish war, or his brother Tiberius Alexander, Titus’ Jewish chief of staff during the siege of Jerusalem. These individuals had both the technical knowledge of Judaism and the ethical perspective required to create Christianity. The New Testament, continuing its parallels with

Wars of the Jews

, mentions in Acts both an Alexander,

144

believed by most scholars to actually be Tiberius Alexander, and a Bernice.

To recognize that a puzzle exists the reader must, once again, recognize parallels—in this case, that Catullus and Judas, the identifier of Jesus, share a number of attributes.

The most obvious parallel between the two is that Catullus dies in the same improbable manner—unknown to medical science—as Judas. That is, “his very entrails … fell out of his body.” This is an exact parallel to the death of Judas.

And falling headlong, he burst asunder in the midst, and all his bowels gushed out.

145

The description of Judas’ bowels gushing out does not occur in the Gospels but in Acts. The event is in the New Testament at this point, to maintain its parallel with the events in

Wars of the Jews

. The parallel “gut spillers” create another prophecy in Jesus’ ministry that is fulfilled in Titus’ campaign.

Judas and Catullus are also parallels in that both of their accusations involve a messianic individual, and neither is true. Josephus, Bernice, and Alexander certainly did not initiate a religion, or “innovation,” led by a Messiah-like member of the Sicarii. They would have established just the opposite kind of “innovation.” Jesus is, of course, famous for having been innocent. He was certainly not the type of Sicarii military leader that Pontius Pilate would have needed to crucify. In fact, Jesus was the exact opposite of such an individual.

The technique establishing that there is a puzzle needing to be solved is the same one used throughout the New Testament and

Wars of the Jews

—that is, parallels. As with the Decius Mundus puzzle in the following chapter, unusual parallels between characters invite the reader to seek an explanation. But to solve the puzzle that the parallels create, the reader must step out of the surface narrative and into another perspective. The reader has to relate to the text from a broad rather than a narrow perspective and has to be prepared to think the “unthinkable,” to seek a solution that is outside the flow of information provided by the surface narration.

I would note that the satirical system that unites the New Testament and

Wars of the Jews

can be seen as an exercise in mind expansion, in that to solve the puzzles the reader must learn to think “outside the box,” so to speak. The authors were making the point that the narrow focus the Sicarii Zealots maintained regarding only a few scrolls was a limited and inaccurate mode of thought. The authors seem to be suggesting that only by seeing all sides of a problem can the truth be known. Therefore, it is possible that they designed the New Testament as a tool to intellectually uplift the messianic rebels. If such was the authors’ intention, it only adds to the incredible nature of the work, which is perhaps more amazing when seen as a secular psychological device rather than as a world-historical religious work.

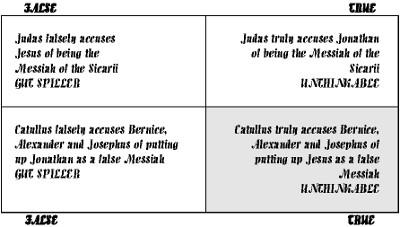

The puzzle that explains the parallels between Judas and Catullus is designed to turn the two stories from tales that relate what is false into tales that state what is true.

To solve the puzzle the reader must simply do as Decius Mundus recommends in the following chapter and “value not this business of names.” To create the “truth,” simply switch the names of the messiahs. Thus, had Judas named “Jonathan” as the Messiah who needed to be crucified, and Catullus had accused Josephus, Bernice, and Alexander as having put “Jesus” “up to what he did,” both passages would be transformed into the truth. Jonathan was a Sicarii messianic leader who, from the perspective of the Romans, deserved to be crucified, and Jesus had “been put up to what he did”—that is to say, was created by—Josephus, Bernice, and Alexander.

The fact that the “Alexander” who participated in the plot is described as Bernice’s husband helps us see the subtle point. Because the Alexander who was Bernice’s husband was dead before the war broke out, it is not Josephus, Bernice, and her late husband who are being identified here. It is the families of these individuals who authored the Gospels—the Flavians, Herods, and Alexanders.

I would again note that the authors of the New Testament seem to be stating that one could not know the truth unless one considers more than one book or scroll, that is, unless one reads intertextually. In this case, Acts and

Wars of the Jews

create the parallels. I suspect that the authors are being critical of the Sicarii Zealots, who believed that they could know the truth from a very limited set of documents. The authors are presenting a real-life example of the inaccuracies that occur whenever readers cannot look beyond the single narrative in front of them.

Josephus concludes

Wars of the Jews

with the following paragraph. He was insistent that he wrote the truth “after what manner this war of the Romans with the Jews was managed.”

And here we shall put an end to this our history; wherein we formerly promised to deliver the same with all accuracy, to such as should be desirous of understanding after what manner this war of the Romans with the Jews was managed.

Of which history, how good the style is, must be left to the determination of the readers; but as for its agreement with the facts, I shall not scruple to say, and that boldly, that truth hath been what I have alone aimed at through its entire composition.

146

Josephus, like the Apostle Paul, reminds the reader over and over that he is writing the “truth.” Perhaps this is one of the reasons the authors of the New Testament and the works of Josephus create the elaborate system by which their authorship of Christianity could be known. They did not wish those in the future, who would one day discover the truth, to think of them as liars.

CHAPTER 11

The Puzzle of Decius Mundus

I believe that the Flavians did not intend to have sophisticated people like themselves take their invention, Christianity, seriously. Josephus describes the individuals who fomented the rebellion in Judea as “slaves” and “scum.” These are the individuals that Rome would have seen as being susceptible to an infatuation with militant Judaism. It was for this group,

hoi polloi

, that they created the religion.

This is why the authors of the New Testament and Josephus felt free to put into their creations the puzzles and lampoons that “notified” the educated of the true origin of the religion. They did not believe that the masses—the uneducated slaves and peasants for whom Christianity was intended—would understand these puzzles, an assumption that has proven to be correct. However, they certainly wanted the puzzles to be solved eventually. Only then could Titus’ greatest achievement—that of transforming himself into “Jesus”—be appreciated.

My interpretation of the following passages is that they create a puzzle whose solution shows how the puzzles in the New Testament can be solved. The puzzle itself is quite easy to solve; the only difficult aspect of it is recognizing that the puzzle exists.