Candyfloss (16 page)

Authors: Nick Sharratt

‘Definitely!’

‘You’re kidding me,’ said Dad, but he was looking down at his old jersey and jogging bottoms. ‘Hey, I look a terrible scruffbag. I’d better change out of these old togs.’

‘Well, I’m going to change

into

my old togs,’ I said. ‘I look stupid in this outfit, don’t I, Dad?’

‘You look very glam and gorgeous, my darling, but not quite

my

little girl. So yes, you get changed too.’

Dad got dressed up in his best jeans and blue shirt and I got dressed down in my old jeans and stripy T-shirt. I checked on Lucky – several times – and left a bowl of food near her and a box of torn-up newspaper as a makeshift litter tray.

Then Dad and I set off for the fair.

It wasn’t there!

There was just an empty field with some muddy tracks and litter blowing in the wind. We both stood staring, madly waiting for it to materialize in front of our eyes. But there were no vans, no rides, no roundabout, no candyfloss stall.

Dad blinked and shook his head. ‘Oh dear. Of course. It’s moved on somewhere else. As fairs do. I am a fool. Sorry, Floss.’

‘Where’s it gone, Dad?’

‘Search me. There aren’t any posters or anything. Poor poppet, you’ve missed out on your ride on Pearl.’

‘And my candyfloss.’

‘Yes. Sorry.’

‘Can’t we . . . can’t we go and look for it someplace else?’

‘Well, where, pet?’ Dad said helplessly. He looked all round and then spotted the pub on the corner. ‘Let’s see if they’ve got any idea.’

We hurried to the pub. I hung around the doorway while Dad went in and asked. He came out sadly shaking his head.

‘No one has a clue. Oh well. Can’t be helped. Look, they’ve got a pub garden. Would you care to join me for a glass of something fizzy, sweetheart?’

Dad had a beer and I had a lemonade sitting huddled up on the wooden furniture. There was a little plastic slide and a Wendy house in the garden,

Tiger

-size. I wondered what he was up to in Australia. Maybe he’d forget all about me in six months. Steve probably

wanted

to forget about me. But I knew Mum was missing me. She kept phoning me, and once or twice it sounded as if she might be crying.

‘Dad, what are we going to do about Mum phoning? Will we give her Billy the Chip’s number?’

‘Oh dear, I don’t know. I – I wasn’t actually going to tell her we were moving, as it were. I know she’ll think it’s not suitable, our living at Billy’s.’ Dad put his pint mug down, sighing. ‘Who am I kidding? It’s

not

suitable, dragging you off to some funny old man’s house. Goodness knows what state it’s in. He seemed a bit fussed about it, didn’t he? Oh Lordy, Floss, I hope this works out.’

‘Of course it’ll work out, Dad.’ I put my glass down too and felt in my jeans for my pocket-money purse. ‘Right, it’s my round now, Dad. What are you having, another beer?’

Dad laughed and ruffled my curls but wouldn’t let me pay. He bought another pint for himself, another lemonade for me, and a packet of crisps each.

We walked home holding hands. Lucky greeted us sleepily when we came in, giving us little mews of welcome, as if she’d been our cat ever since she was a newborn kitten

.

14

WHEN I GOT

to school on Monday Rhiannon was strolling round the playground with Margot and Judy. They had their arms linked, their heads close together. I hovered, not sure whether to run up to them or not.

‘She’s like

so

boring now,’ said Rhiannon. ‘But Mum says I’ve got to be kind to her, though I don’t see

why

. We bought her, like,

the

most exquisite outfit because her clothes are, like, so pathetic.’

‘And babyish,’ said Margot.

‘And smelly,’ said Judy.

They all tittered.

‘But it was, like, a waste of time because she barely said thank you!’

I started trembling. I ran right round them and shouted, ‘Thank you thank you thank you!’ right in Rhiannon’s startled face.

‘Hey, cool it, Floss!’ said Rhiannon, giggling uneasily.

‘I didn’t want the denim outfit. I didn’t want to go out with you on Saturday! I wanted to see Susan and I wish wish wish I had!’ I shouted.

Rhiannon stopped laughing. Her face hardened, the delicate arches of her eyebrows nearly meeting in the middle. ‘Yeah, it figures. You and Swotty Potty. You’re a right pair. You deserve each other. You be friends with her then, Smelly Chip.’

I

wanted

to be friends with Susan, but I wasn’t sure she still wanted to be friends with me. I saw her way over at the other end of the playground, walking by herself, tapping each slat of the fence. I hurried towards her but she saw me coming and ran into school.

‘Susan! Wait! Please, I want to talk to you,’ I shouted, but she didn’t even turn round.

I ran to the school entrance and rushed to the girls’ cloakrooms, where we’d always met before. I barged straight through two girls giggling together.

‘What’s up with Floss?’

‘Maybe she’s got galloping diarrhoea?’

They cackled with laughter while I ran up and down the toilets. They were all empty. There was no sign of Susan.

I set off down the corridor, charged round the corner and ran right into Mrs Horsefield, nearly knocking her flying.

‘Oh! I’m so sorry, Mrs Horsefield,’ I gabbled.

‘It’s good you’re in such a hurry to come to school on Monday morning, Floss,’ said Mrs Horsefield. She held me at arm’s length. ‘But you don’t look too happy, my dear. You’re not running away from someone, are you?’

‘No, no, I’m trying to run

to

someone,’ I said.

‘Well, I hope you find them,’ said Mrs Horsefield. She paused. ‘If that someone’s Susan, I think I saw her going into the library.’

‘Oh

thank

you, Mrs Horsefield.’

‘Don’t be too long finding her now. Registration’s in five minutes.’

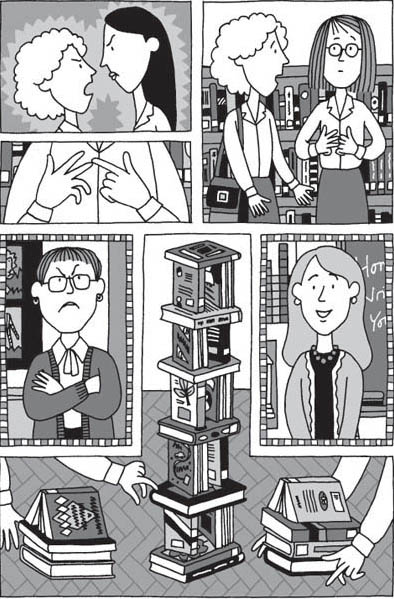

I set off for the library. Susan was standing by the shelves, fingering her way along the first row of books as if she was playing them like a piano.

‘Susan!’

She jumped, and dodged round the other side of the bookshelves.

‘Susan, you can’t keep running away from me like this! You’ll be sitting in front of me in five minutes. Please listen to me. I’m so so sorry I wasn’t completely honest about Saturday. I was just so stupid and I feel awful now. I don’t know why I went to Rhiannon’s. I didn’t have a good time at all. I don’t want to be friends with her any more. I want to be friends with you. Please say you forgive me. Will you come to my place next Saturday and we’ll have fun together and eat Dad’s chip butties?’

Susan blinked at me as I spoke, twitching her fingers. There was a little pause when I stopped.

‘Do you know, you said exactly one hundred words,’ she said in a matter-of-fact way.

‘Susan, please, did you

listen

to what I was saying?’

‘Yes, I listened. You want to be my friend now because Rhiannon’s gone off with Margot and Judy.’

‘No! Well, yes, she

has

, but

I

broke friends with her, I truly did.’

‘Yes, well, whatever. Only the thing is, Floss, I don’t really want to be your second-best friend.’

‘No, I want you to be my

first

-best friend.

Will

you come next Saturday?’

Susan shrugged. ‘I think I’ve probably got something on next Saturday.’ She paused. ‘I have to go to this conference thing with my parents. Maybe the Saturday after?’

‘That won’t be any

use

. Oh Susan, we won’t have the café any more. Please don’t tell anyone, but my dad hasn’t kept up all his payments and we have to move out and we’re going to stay at Billy the Chip’s place but it sounds like it’s going to be really weird and Dad’s going to run his van outside the station and that’s going to be weird too and what am I going to do when Dad’s out working and I’m a bit scared about it but I haven’t

liked

to say because Dad’s so fussed about everything.’

‘Oh Floss!’ said Susan, and she put her arms round me.

I started crying and she patted me on the back.

‘You

won’t

tell anyone, will you?’

‘Of

course

not! I won’t say a word. I’m sure I’ll be able to come on Saturday. I don’t

want

to go to my parents’ conference one bit – they just haven’t got anyone to leave me with. Hey, Floss, did you know you said

another

exact hundred words. It’s like you’ve got this weird gift! One hundred is my all-time lucky number too.’

‘So we’re friends now?’

‘Best friends,’ said Susan, giving me a squeeze. ‘I’ve wanted to be your best friend ever since I came to this school. Are you sure you’re OK about it though? Rhiannon might start being your worst enemy now.’

‘I don’t care,’ I said, though my heart began thudding at the thought. ‘I wish I didn’t still have to sit next to her.’

‘Don’t worry,’ said Susan. ‘If she tries any funny business I’ll turn round and yank her off her chair again.’

‘Yes, she looked so

surprised

when she landed on her bum,’ I said, and we both giggled.

‘She’ll be even more nasty and totally mean

when

she finds out about Dad and me leaving the café and going to live with Billy the Chip. And I don’t know what will happen when he comes back from seeing his son. Dad says I should go to Australia to be with Mum, and there’s a bit of me that wants to, but I can’t leave Dad, I’m all he’s got. Well, he’s got Lucky too, but she’s really my cat. OK, we’ll have to see if she belongs to anyone else but I’m hoping like anything she’ll be mine.’

Susan was counting on her fingers as I spoke. She stared at me in awe. ‘That’s

another

hundred! You are a total phenomenon, Floss.’

‘A what?’

‘A phenomenon. It means you’ve done something utterly extraordinary.’

‘A phenonion?’ I tried hard but I couldn’t say it.

I started mixing Susan up too, so that neither of us could say it without spluttering with laughter.

‘Seriously though,’ I said, wiping my eyes. ‘Would you say it’s a good omen?’

‘I’ll say!’

‘Dad and I keep waiting for our luck to change. Well,

some

good things happen, but most of all I’d like Dad to keep his café. No,

most

most of all I’d like my mum and dad to get back together, but there’s no chance of that. I wish there wasn’t such

a

thing as divorce. Why can’t people stay together and be happy?’

‘Well, people change,’ said Susan. ‘Like friends. My parents are divorced.’

‘

Are

they? So do you live with your mum or your dad?’

‘Both. No, they’re married to each other now, my mum and dad, but they used to be married to different people. I’ve got all these stepbrothers and stepsisters. My family’s pretty complicated.’

‘But suppose your mum and dad did split up. Who would you live with then?’

Susan thought about it. I could see her brain trying to puzzle it out, as if it was a complicated sum. She frowned. ‘I don’t know! It must be so difficult for you, Floss.’

‘I got used to having two homes, but now my mum’s house is let out to strangers and my dad’s café is going to be taken over so I haven’t got

any

real home. Dad and I have this joke about living in a cardboard box like street people. I used to sit in a cardboard box when I was little and pretend it was my Wendy house. It was my best ever game for ages. I used to cram a cushion into the box and a little plastic cooking stove and my dolls’ teaset and all my favourite teddies.’ I saw Susan was counting again and I caught hold of her fingers. ‘Don’t count my words, it makes me feel weird.’

‘OK, I won’t. Sorry. Tell me more about the cardboard box house.’

‘In my mind it had a proper red roof with a chimney, and honeysuckle grew up the walls. I tried crayoning it on the box but it just looked like scribble. There was a blue front door with a proper knocker. If Dad was playing with me I’d make him pretend to knock on this imaginary knocker when he came calling. He was too big to get in the box with me – the walls would have collapsed – so he always said he’d like to sit in the garden on a deckchair. I’d get this stripy towel and put it just beside the box and he’d lie on it. I’d make him a cup of tea. Not

really

: I’d just put some water in my plastic teacup, and I’d colour it a bit with brown smarties. It probably tasted disgusting but he always drank it right up, his little finger sticking up in the air to make me laugh. I

loved

playing house with my dad.’

‘I can see why you’d want to stay with him now. My dad didn’t ever play with me like that, not in a fun way. He played cards and taught me chess and read to me, but he didn’t ever muck about. I played by myself mostly. I didn’t make things up like you, my mind doesn’t seem to do that, but I

did

play with cardboard boxes, little ones. I made a row of shoebox houses in my bedroom once, and then I started making whole streets with boxes of

bricks

, and lots of books too – they make very good buildings.’

‘Show me,’ I said, thrusting an armful of library books at her.