Candyfloss (20 page)

Authors: Nick Sharratt

‘And what about if I go to the moon? Will you come and visit me in your spacesuit and do a dance with me in your moonboots?’

I did a slow, bouncy moon dance. Susan joined in. We danced in and out and round about the cardboard boxes.

Dad put his head round the door and laughed at us. He put an empty cardboard box on each foot and lumbered about doing his own crazy moon dance – and then we all collapsed, laughing.

‘I don’t know what I’m doing clowning around. There’s still so much to be done,’ said Dad.

‘I’ve just got to pack up my books and crayons

and

stuff in my pink pull-along case, and then we can help you, Dad,’ I said.

‘We can number each box and write on it what’s inside,’ said Susan.

‘You’re obviously a girl with a system,’ said Dad.

Susan was great at getting both of us organized. She found some old brown sticky tape and sealed each box so we could balance one on top of the other.

We finished my room, though we left out clean clothes for tomorrow, and Ellarina and Dimble and my sewing set and Lucky’s duvet. She didn’t like all this sudden activity and burrowed right underneath the duvet, just her nose and whiskers peeping out.

Dad started to tackle his bedroom while we got started on the living room. There wasn’t really much to take. We packed:

- The cuckoo clock (though it didn’t work). It had been Mum and Dad’s wedding present from Grandma, and for as long as I can remember the hands had been stuck at four o’clock and the cuckoo sulked inside his house, though you could still see him if you opened the little doors.

- The motorbike calendar. Dad had inked stars and smiley faces every weekend

with

Floss

written in curly writing. Last month he’d written

Floss! Floss! Floss!

in every single box. - The photo of Mum and Dad and a baby me at the seaside, all sitting on the sand and licking ice cream. I remembered that day and the heat of the gritty sand and the coldness of the ice cream dripping onto my tummy.

‘You were such a cute little toddler, Floss. Look at all your fluffy curls,’ said Susan. ‘Your mum’s ever so pretty too. She looks so young!’

Mum was cuddled up to Dad in the photo, licking his ice cream instead of her own. Dad was pretending to be cross with her but you could still see just how much he loved her.

I sighed. ‘I wish I could rewind to when we were all happy together,’ I said. I sniffed hard.

Susan patted my shoulder sympathetically. ‘We could really do with some bubble wrap,’ she said. ‘Never mind, we’ll have to make do with newspaper.’

We were leaving the television because it didn’t work properly anyway. I packed all my favourite films (number 4 on the list), hoping that Billy the Chip might have a video recorder, though if his crackly old transistor radio was anything to go by he didn’t seem up to speed with his electrical equipment.

We were leaving the table and chairs. The tabletop was patterned with coffee-mug rings and the woven seats of the chairs were coming unravelled and scratched your bottom. Even so, I sat down on each one, remembering when we were Mum and Dad and me, with one leftover chair for all my teddies and Barbies. They were forever falling off, the teddies too limp to sit up properly, and at the slightest nudge the Barbies jackknifed onto the floor with their legs in the air. Mum would get cross but Dad always helped me get them back on their chair. He’d sometimes put a baked bean or a chip on each of my doll’s house plates for my fidgety family.

‘Did your dad really never play pretend games with you when you were little, Susan?’ I asked.

‘He read to me and did funny voices. And he played weighing and measuring games and guessing words on pieces of card, but that was like baby lessons. My mum played music to me and I had to act it out. Sometimes we played I was a little French girl called Suzanne, but that was so I could count up to a hundred in French.’

‘You’re such a brainybox, Susan,’ I said.

‘Don’t!’ said Susan, as if I’d insulted her.

‘I’m paying you a compliment! You’re heaps and heaps brainier than me.’

‘It’s not that great a deal being brainy,’ said Susan. She sat down on the sofa, sighing.

I went to sit beside her. The sofa sagged badly and the corduroy was shiny with age. There were several big dark stains where Dad had spilt his coffee or his can of beer. We were leaving the sofa too. I wished we could somehow take it with us. It wasn’t just because it was where Dad and I cuddled up and watched the telly. When I was little it had been a fairytale castle and a wagon train across the prairie and a bridge over the man-eating crocodiles crawling across the carpet.

‘I wonder if we could just take one of the sofa cushions?’ I said, tugging at it.

‘It’s a bit . . . tired looking,’ Susan said, as tactfully as she could. ‘And it would take up a whole cardboard box all by itself.’

‘Yeah, I suppose,’ I said, stroking the sofa as if it was my giant pet.

‘Shall we go and see how your dad’s getting on with his packing?’ Susan said, going for diversionary tactics.

Dad was having similar problems. He was slumped on the edge of his bed, his clothes scattered all over the duvet, so it looked as if there were twenty Dads sprawled beside him. There were Mum things too, clothes I’d completely forgotten about – an old pink towelling dressing gown, a sparkly evening frock with one strap drooping, a worn woollen jacket with a furry collar, even some old

Chinese

slippers, embroidered satin, with one of the butterflies unravelling.

‘Dad?’ I said, and I went and sat beside him while Susan hovered tactfully in the doorway. ‘Where did all Mum’s stuff come from?’ I picked up one of the slippers, rubbing my finger across the satin. I remembered sitting watching television long ago, leaning back against Mum’s legs, stroking her satin slippers, feeling the little ridges of embroidery with my fingertip.

‘Your mum left them in her half of the wardrobe when she went off with Steve. She didn’t want them. I was supposed to get rid of them but I couldn’t.’ Dad sighed, shaking his head at himself. ‘Daft, aren’t I, Floss?’

‘You’re not daft, Dad.’

‘I suppose it’s time to deal with them now.’

‘You can still keep them. We can pack them all up in a cardboard box.’

‘No, no. It’s time to chuck them out. Time to chuck half of my stuff too.’ Dad picked up the jeans that had got torn at the fair and flapped the tattered legs at us.

‘I thought you were going to keep them as decorating trousers.’

‘Who am I kidding? When was the last time I did any decorating, for heaven’s sake?’

‘You painted my chest of drawers silver.’

‘And left it half finished.’

‘I still love it. Can I take it to Mr Chip’s house, Dad? It won’t take up much room.’

‘OK OK. Definitely, little darling. So how are you two girls getting on with packing up your bedroom, Floss?’

‘We’re finished, Dad. Susan’s absolutely ace at getting everything sorted.’

‘Well, aren’t we lucky! Thank you so much, Susan, you’re a sweetheart. I wish

I

had a smashing friend to sort me out,’ said Dad.

‘I’d like to be your friend too, Mr Barnes,’ said Susan. ‘We can start sorting your clothes for you, if you like.’

‘That’s very kind of you, Miss Potts,’ said Dad. ‘And

I

could sort out a tasty snack, seeing as you’ve both worked so hard. Now let me see . . . would you like chip butties – or chip butties – or indeed, chip butties?’

We both put our heads on one side, pretending to consider, and then yelled simultaneously, ‘

Chip butties!

’

It was a joy to see Susan eating her very first chip butty. Dad served it to her on our best blue china willow-pattern plate, garnished with tomato and lettuce and cucumber. Susan ignored the plate and the little salad. She didn’t use the knife and fork Dad had set out beside the plate.

She

picked up the chip butty in both hands, staring in awe at the big soft roll split in half and crammed with hot golden chips. She opened her mouth as wide as possible and took a big bite. She shut her eyes as she chewed. Then she swallowed and smiled.

‘Oh thank you, Mr Barnes! It’s even better than I hoped it would be. You make the most wonderful chip butties in the whole world!’

After we’d eaten every mouthful of our chip butties we sorted Dad’s clothes into

GOOD, NOT TOO BAD

and

CHUCK

. Susan counted and I made a list.

Dad’s clothes:

GOOD

– 12 items of clothing, including one tie and socks and shoes and underwear.

NOT TOO BAD

– 20 items of clothing

CHUCK

– 52 ½ items (the half was an ancient pair of pyjama bottoms – we couldn’t find the top).

Dad laughed ruefully and started obediently chucking his stuff into a big plastic bag. He took Mum’s old clothes, hesitated, and then started chucking them too.

‘Maybe we don’t have to chuck all of them, Mr Barnes,’ said Susan. ‘We couldn’t have them, could we?’

‘Do we want to dress up in them?’ I asked a little doubtfully.

‘No, we want to make them into clothes for Ellarina and Dimble,’ said Susan.

We borrowed Dad’s sharp kitchen scissors and some greaseproof paper to make patterns. It took a

lot

longer than I’d realized, but after two extremely hard-working hours Ellarina had a sparkly strapless dance dress, Dimble had a fur coat and they both had pink dressing gowns, and tiny embroidered slippers tied to each of their four paws with sewing thread.

‘We’ll cut the legs right off your dad’s ripped jeans and make them little denim jackets and Ellarina can have a skirt and Dimble can have dungarees – he’d look so cute!’

‘And caps?’ I asked.

‘Well, I could give it a go. Just so long as you don’t ever ever ever wear yours,’ said Susan. She waggled her fingers. ‘They

ache

now.’

‘Mine too. Yet I wanted to work on our friendship bracelets.’

‘We can do them another time,’ said Susan. ‘We’re going to have lots and lots of times. You will come to my house, won’t you, Floss?’

‘And I’m sure Billy the Chip won’t mind you coming to his place. And then . . .’ My voice tailed away. I didn’t have any idea where we’d be after that. It was so scary not knowing. ‘Let’s go and

have

a swing,’ I said quickly. ‘It goes a bit wonky but you can still swing quite high if you really kick your legs.’

We went out to the back yard. Lucky came with us and circled the wheelie bins. I always worried whenever she slipped out of sight, but she bobbed back each time.

I let Susan have first go on the swing, but she wasn’t really any good at it, so I stood on the seat behind her and pulled on the ropes and bent my knees and got the swing going. We didn’t really go

that

high, but we pretended we were swooping right up in the air, over the treetops, flying far over the tallest tower, up and up and up.

‘Wheee! We’re right over the sea now,’ I shouted. ‘And there’s land again! See all those skyscrapers? We’re over America!’

‘I think it’s more likely France,’ Susan said breathlessly.

‘No, no, look, more sea, we’re swooping r-o-u-n-d and d-o-w-n and here’s Australia! See all the kangaroos? Whoops, there’s a boomerang. Who’s that waving? It’s my mum! Hey there, it’s me, Floss. Meet my best friend Susan.’

We both let go of the swing with one hand and waved wildly into thin air

.

18

ON SUNDAY MORNING

Dad and I loaded all the neatly labelled cardboard boxes into the van. Then Dad struggled with my silver chest of drawers and my swing. He crammed in his old CD player and all our pots and pans and crockery and a box of vital tools I’d never seen him actually use.

He dithered for a long time out in the yard, shifting all the bits of motorbike under the tarpaulins. He laid them all out on the concrete, as if they were parts of a jigsaw puzzle and if he could only sort them all out systematically he’d be able to construct a splendid Harley Davidson there and then. He actually moved pieces around as if he was looking for a piece of sky or a flat edge. Then he sighed.

‘What am I going to do with it all, Floss?’ he said. ‘I’ve been collecting all this stuff for years and years, right from when I was in my teens.’

‘Take it with us, Dad.’

‘Yes, but what am I going to

do

with it?’

‘Make your own custom-built motorbike, Dad. How cool would that be?’

‘Yeah, yeah, if I were still twenty years old – but I’m pushing forty, Floss. I’m a tubby old dad. I doubt I’ve got the bottle for roaring round the roads on a bike, even if I had one. No, I might as well leave the lot here. Maybe someone else will find all the spare parts useful, eh?’

‘But you like them so, Dad. They’re part of you.’

‘You’re the only part of me I want to keep for ever, Flossie. It’s time to move on. It’s goodbye to Charlie’s Café.’

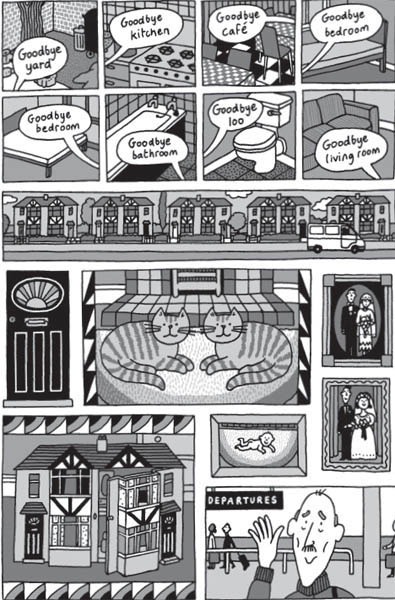

‘Let’s go round and say goodbye to every room, Dad. Would that be totally nuts?’

‘OK, darling, let’s go on a little tour of the premises.’