Candyfloss (18 page)

Authors: Nick Sharratt

‘I think you’ll survive this savage attack, Rhiannon,’ she said. She picked up the ruler. ‘I take it this was the weapon involved?’

‘It hurt!’ said Rhiannon.

‘I’m sure it did,’ said Mrs Horsefield. She looked at me. ‘Were you the culprit, Floss?’

I nodded. I thought Mrs Horsefield would shake her head and sigh at me and maybe tell us both off a little bit, but it wouldn’t be

serious

. But she didn’t shake her head or sigh. She put her hands on her hips and looked very very very serious.

‘Flora Barnes, I’m ashamed of you,’ she said coldly. ‘I’m very disappointed that you’re behaving so badly nowadays.’

‘I’m sorry, Mrs Horsefield,’ I whispered.

‘Sorry isn’t good enough. I can’t keep making excuses for you. You waltz into the classroom ten minutes late, and you don’t concentrate properly when you are here. I’m going to have to think of a serious punishment.’

I bent my head, burning all over. I wanted to lay my head on my desk and weep. I felt so awful. I couldn’t understand why Mrs Horsefield was so very angry with me.

‘Please, Mrs Horsefield, I have a strong feeling Floss was provoked,’ said Susan.

‘You be quiet, Susan. Nobody asked your opinion,’ said Mrs Horsefield, totally snubbing her.

Rhiannon was still groaning theatrically, rubbing her ribs, but her eyes were glittering. She was hugely enjoying our humiliation.

‘Poor Rhiannon,’ said Mrs Horsefield. ‘I won’t have you teasing and tormenting her any longer, Flora. Gather up all your books and pens and pencils, please. Put them all in your school bag and stand up.’

I stared at Mrs Horsefield. Was she sending me to the head for the whole day? Was she

suspending

me? Was she

EXPELLING

me?

The whole class was silent, stunned. Even Rhiannon looked startled. I shoved my stuff in my school bag, my hands fumbling. I stood up, shocked and shaking.

‘Right. I’m going to move you away from Rhiannon, seeing as you can’t behave nicely sitting next to her. Now, where can I put you?’ Mrs Horsefield seemed to be looking all round the classroom for a spare seat. There was only one empty chair. Mrs Horsefield looked at Susan’s desk. She pointed to it.

‘Well, Flora, you’d better sit here for now. Susan, move the desk forward as far as it will go, right away from Rhiannon. That’s it, I’ll have you both beside my desk, where I can keep on eye on you. There now. Sit beside Susan, Flora.’

I collapsed onto the seat next to Susan – and Mrs Horsefield gave me the tiniest private wink.

16

SCHOOL WAS HEAVENLY

now I was sitting next to Susan. I even enjoyed maths. Well, I didn’t exactly

enjoy

it, but it was quite companionable having Susan go through each sum with me and tell me what to do.

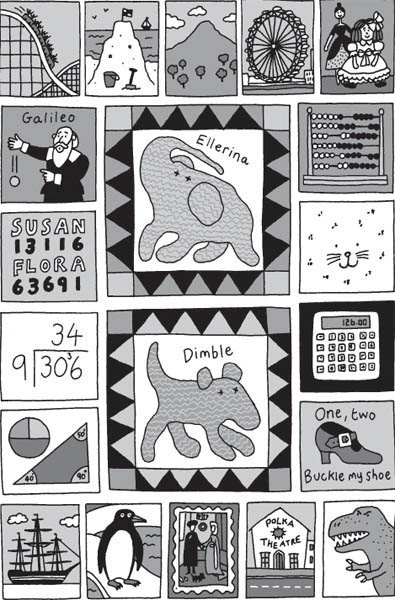

We also started a numbers project together in a notebook exactly a hundred pages long. Susan wrote about famous mathematicians like Galileo and Pythagoras. I found out about numerology, and wrote out my name and Susan’s name and checked off all the vowels and consonants and found out we were deeply compatible (but we knew that anyway). Susan wrote out neat examples of addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. She even did really difficult stuff her dad had taught her like algebra and geometry. I coloured in all her circles and triangles. Susan wrote about the abacus. I invented my own join-the-numbered-dots puzzle. Susan did a wonderful diagram of a calculator. I

copied

out counting rhymes like

One, Two, Buckle My Shoe

.

Mrs Horsefield said it was excellent and she’d definitely mark it ten out of ten. Rhiannon muttered behind us, ‘

One, two, don’t they make you spew? Three, four, they’re such a bore. Five, six, up to nerdy tricks

.’

As if we cared! I started making a list of all the things Susan might want to do on Saturday. The café was closing for good on Friday so Dad would be free to take us anywhere. I thought about all the special treat days I’d had with Mum and Steve.

On Saturday Susan and I could:

- Go to Chessington World of Adventures in Dad’s van and go on all the rides, even the scary ones.

- Go to the seaside in Dad’s van and have ice creams on the pier and make a ginormous sand castle and go on a boat trip.

- Go to the country in Dad’s van and walk up to the top of a big hill and have a picnic and paddle in a stream.

- Go up to town in Dad’s van and go on the London Eye and Dad can row us on the Serpentine and we can play in Princess Diana’s park.

- Go to Bethnal Green toy museum in Dad’s van and we can count all the dolls and look at the dolls’ houses and play Giant Draughts.

- Go to Greenwich in Dad’s van and run all the way through the tunnel under the river and go to the market and see the

Cutty Sark

. - Go to London Zoo in Dad’s van and see all the monkeys and the elephants and the penguins and watch them being fed.

- Go to the National Gallery in Dad’s van and choose our top ten favourite paintings and then climb on the lions in Trafalgar Square.

- Go to the Polka Theatre in Dad’s van and ride on the rocking horse and see a play and then have a pizza afterwards.

- Go to the Natural History Museum in Dad’s van and see all the dinosaurs and then have tea in the shop over the road and be allowed two cakes each.

Memo

: We

don’t

want to go to the Green Glades shopping centre.

I showed Dad the list when he tucked me up in bed that night.

‘What about going to Disneyland in Dad’s van?’

he

said. ‘Going for a world tour in Dad’s van? Flying to the moon in Dad’s van?’

‘I suppose I got a bit carried away,’ I said, wanting to kick myself. I’d forgotten just how much most of those days out would cost.

‘I wasn’t being

serious

, Dad. I was just making a silly list. You know what I’m like. No, we could just go for a little drive out in the van, maybe for a picnic. Or we could just go to the park. Maybe we’ll skip feeding the ducks – Susan might feel she’s a little too old, though of course

I

love feeding them. Oh Dad, if only the fair was still here! Wouldn’t that be great! We could go on the roundabout. Susan and I could squash up on Pearl together and we could both have a candyfloss from Rose’s stall. Maybe she’d invite us all back to her lovely caravan. That would be sooo fantastic.’

‘Yes, it would be,’ said Dad. ‘Only the fair’s not here. And I’m afraid I just don’t have the cash for the other outings. I’ve got to be careful with petrol too. I reckon we might need a couple of trips to Billy’s house with all our stuff, and then I’ve promised to drive him to the airport.’ Dad paused. ‘I went round to Billy’s today, Floss. It’s . . . it’s a bit . . .’

I looked at Dad. ‘It’s a bit what, Dad?’

Dad gestured vaguely, his arms stretched wide. ‘Well, you’ll see for yourself. I’ll do my level best to make you a pretty little bedroom somehow.

Everything

will be OK. Touch wood.’ He tapped his head and then glanced around my bedroom. He looked at the faded fairy wallpaper I’d had ever since I was a baby, the curtains falling off the rail, the wonky chest of drawers half painted silver, the pale pink carpet, which was now sludge-grey with age.

I sighed. I thought about the time when it was all new and clean and fresh, and Mum and Dad tucked me up in bed together and took turns telling me stories about the fairies flying up the wall.

Dad sighed too. ‘I’m not much cop at the decorating lark, am I, Floss?’

‘Never mind, Dad.’

‘I’m not much cop at

anything

, am I?’

‘

Don’t

, Dad. You’re fine.

We’ll

be fine, you, me and Lucky.’ I picked her up and held her close. ‘Did you meet Billy the Chip’s cats, Dad? What are they like?’

‘Well, they’re huge compared with our little Lucky.’

‘Oh no! Do you think they’ll bully her?’

‘No, no, I think they’re too old and tubby to do anything much but sleep.’ Dad yawned. ‘Like your old dad. I’m totally knackered, Floss, and yet I’ve still got to get to grips with all this packing. I’m so sorry, darling, but I’m going to be busy most of Saturday. I think you and Susan will just have to amuse yourselves.’

‘But you’ll make chip butties, won’t you, Dad?’

‘I’ll make you chip butties fit for a queen. Well, two little princesses.’

Dad gave me a big kiss on my curls and he gave Lucky a big kiss on her fur, and then he tucked us both up, me in bed, Lucky in her duvet nest. I snuggled down with Dog and Elephant. I twiddled Elephant’s trunk round my fingers and tucked Dog’s limp ear over my nose like a little cuddle blanket. I was becoming very fond of them. I didn’t exactly

play

with them, but they were starting to develop personalities. Elephant was called Ellarina, and was a bit flighty. She liked to show off and twirl her trunk in the air. Dog was called Dimble. He quivered at any sudden movement or loud noise. He did his best not to look at all mouselike whenever Lucky was near him.

I couldn’t decide whether to introduce them to Susan. She wouldn’t tease me like Rhiannon but she might

privately

think me a total baby.

‘Do you have any cuddly toys, Susan?’ I asked as casually as I could on Friday morning.

‘You mean teddy bears? No, I think I had one in my cot when I was very little but I don’t have any now.’

‘Oh,’ I said, resolving to hide Ellarina and Dimble under my bed.

‘I’m not

anti

-teddy. I just don’t like the feel of their fur very much. I’ve got uncuddly toys though.

I’ve

got eleven little wooden elephants, one wooden giraffe, one pair of crocodiles with jaws that snap open and shut, and three china rabbits – one pink, one blue and one big green one who towers over all the other animals, even the elephants.’

‘But they’re like ornaments. Do you actually play with them?’

‘Exactly how could I play with them?’ Susan asked.

‘You could give them names and make them funny or naughty or shy, and maybe take them out into the garden and play jungles. You could turn your mum’s washing-up bowl into a watering hole and make a big earth mountain for them to trek up and down.’

‘That sounds a lot more fun than just dusting them,’ said Susan. ‘You do get good ideas, Floss.’ She paused. ‘Would you mind terribly if we didn’t go on one of those special outings on your list this Saturday? I mean, they all sound lovely, and if that’s what you really want to do that’s fine with me, but I’d sooner make the most of our time together just playing. Is that OK?’

‘Of course!’ I said, deeply relieved.

Susan paused again. ‘Look, Floss, this is terribly rude of me, but . . . I couldn’t come in the morning too, could I? I so want to have a proper long time together – and also my mum and dad are supposed to be going to this education conference all day. They’re both giving papers and I was going to have

to

trail along too and lurk in a corner somewhere reading a book, but if you’re kind enough to invite me I could be with you.’

‘Education? Are your mum and dad teachers?’

‘Kind of. They teach teachers how to be teachers. They used to be at Oxford but now they’ve both got jobs near here.’

‘Are they posh?’ I said, and then I blushed because it sounded so stupid.

‘They’d die if anyone thought they were posh,’ said Susan. ‘They

are

posh though – my mum even went to boarding school – but they try to act just ordinary.’

I didn’t quite get this. Rhiannon’s mum and maybe even

my

mum were just ordinary and yet they tried hard to pretend they were posh. It was a novelty to think Susan’s mum and dad pretended the other way round.

‘Well, Dad and I definitely

aren’t

posh,’ I said. ‘And I’d love you to come as early as you want – that would be brilliant – but the whole place is going to be in an awful mess. Dad and I will be packing everything. We wanted to try to get it all done before you came.’

‘Can’t I help? I’m absolutely ace at packing because we’ve moved heaps and heaps of times.’

‘OK then, if you really don’t mind.’

‘That’s what friends are for,’ said Susan.

‘Did you have a best friend at your old school?’

‘Not really,’ said Susan. ‘It’s always horrible starting at a new school because you stick out so, and I seem to be the sort of person that gets picked on. Rhiannon thinks she’s

so

original, but they used to call me Swotty Potty at my old school too. Maybe I ought to change my name by deed poll!’

‘My mum wanted me to change my name when she split up with Dad. She wanted me to add Steve’s name on with a hyphen but I wouldn’t.

He’s

not my dad, he’s not anything to do with me, he’s just my mum’s new partner.’

‘All these partners!’ said Susan. ‘I tried to do a family tree on this big wallchart but it got so complicated. I did it all in my best italic handwriting, in red ink, but then I had to keep crossing bits out because people kept splitting up. Then my mum’s ex-partner kept having new babies with each new lady, so that side of the family tree got much too crowded. It ended up looking such a mess I crumpled it all up and threw it away. That’s why I like maths so. The numbers don’t wriggle about and change; you can just add them up or subtract them or multiply or divide them, whatever, but you always get the answer you want.’