Capitol Men (17 page)

Authors: Philip Dray

K.K.K.

Beware! Beware! Beware!

Your doom is sealed in bloodSpecial Order: Headquarters 17th Division, Cyclopian Cyclop Commandery

At a regular meeting of this post on Saturday it was unanimously resolved that notice be given to J. H. Rainey and H. F. Heriot to prepare to meet their God.

Take heed, stay not. Here the climate is too hot for you. We warn you to flee. You are watched each hour. We warn you to go.

"When myself and colleagues shall leave these halls and turn our footsteps toward our Southern home," Rainey explained, "we know not but that the assassin may await our coming."

However, many in Congress shunned the idea that the federal government might appropriate local authority to address crimes of murder, assault, and trespass. Indeed, many in Congress, including the Ohio Republican congressman James A. Garfield, worried about the constitutionality of such a step as well as the apparent rush to usurp state authority and thus hand Southern Democrats more cause for protest. Others felt that although bold federal laws had been, of necessity, passed in the war's immediate aftermath, now was the time to rein in such impulses. "We have reconstructed, and reconstructed, and we are asked to reconstruct again," declared Representative John F. Farnsworth of Illinois. "We are governing the South too much."

The Nation

expressed an additional fear: that a "Ceasarist" doctrine of federal law enforcement would cause state-level government to atrophy. The magazine called for "restoration of peace and order" in the South "by natural processes" and discouraged the "desperate attempt" to exploit "the humanitarian feelings of the Northern people." Klan outrages, it suggested, were the inevitable result of the ill-conceived disenfranchisement of the South's "natural" leadership and the subjection of Southern whites to "the rule of [the community's] most ignorant members [blacks], aided or managed by knavish adventurers [carpetbaggers]."

The Nation

concluded that empowering the federal government to repress the Klan would simply compound one bad policy decision with another, delaying the moment when the Southern people ultimately made their own peace with the black population in their midst. "We must," it averred, "hand the Government over to the people."

President Grant wrestled with the problem. Certainly, it would be better if local or state law enforcement would put down vigilantism, but it was obvious that the Klan would never be effectively prosecuted that way, for few residents in their areas of operation were bold enough to testify against them, many jurists dared not convict them, and most sheriffs were too frightened or sympathetic to investigate their crimes or hold them in custody. Some Southern courts seemed to act as agencies of the Klan itself. When William Wright, a black citizen of York County, South Carolina, accused Klansman Abraham Sapoch of leading a Klan posse that whipped Wright and set fire to his house, Sapoch slapped Wright with a lawsuit for perjury and false arrest. After a court deliberated, Sapoch was set free to return to his Klan unit, and Wright, the complainant, was dispatched to the state penitentiary.

"Sir, we are in terror from Ku-Klux threats & outrages," a white woman, Mrs. S. E. Lane, the wife of a Presbyterian minister, informed the president in a letter from Laurens County, South Carolina.

Our nearest neighbor, a prominent Repub'can now lies dead, murdered by a disguised Ruffian Band, which attacked his house at midnight. His wife also was murdered ... she was buried yesterday, and a daughter is lying dangerously ill from a shot-wound. My husband's life is threatened [and] we are in constant fear and terror. Ought this to be? It seems almost impossible to believe that we are in our own Land.

Another upcountry white, C. F. Jones, confided that

I am a clergyman, superannuated, dwelling on my plantation, having a number of colored tenants and hired laborers. On Thursday night ... my farm was invaded by a gang of disguised ruffians, who went from house to house, dragging the inmates out, beating them, firing pistols at them, etc. A bullet has since been extracted from the head of

one. Another aged, upright, Christian man, was slaughtered, in his own yard, while begging them to spare him.

Such cries for help were impossible to ignore but could not completely outweigh Grant's concern that federal anti-Klan policies might appear overbearing. Attorney General Akerman, however, was less hesitant; his unusual dual background as a Unionist with powerful Southern sympathies, and his intimate knowledge of life in the rural South, allowed him to grasp more readily than others both the evil the Klan represented and the imperative that it be stopped.

Shortly after graduating from Dartmouth in 1842, Akerman, who had respiratory problems related to a childhood swimming incident, was advised by doctors to relocate to a southern climate. He found employment in South Carolina, tutoring the children of the elite, and later moved to Savannah to serve as a private instructor to the children of John M. Berrien, a U.S. senator and a former attorney general under Andrew Jackson. In exchange Berrien provided Akerman with an education in the law. In 1850 Akerman became an attorney in Habersham County, Georgia, and purchased a three-hundred-acre farm, which he worked himself, along with a small "force" of slaves.

Faithful to the principle of the rule of law, he sided with his adopted state when war came, worried that Lincoln's policies toward the South lacked consistency and fearful of the turmoil emancipation might bring. He joined a home guard unit that was activated when Union forces entered Georgia in spring 1864. However, he accepted the war's outcome as inevitable and served as a delegate to Georgia's constitutional convention of 1867â68, believing it his duty "to let Confederate ideas rule us no longer [and] to discard the doctrines of states rights and slavery." Black suffrage had at first seemed to him "an alarming imposition on account of [their] supposed ignorance ... But on reflection we considered that if ignorance did not disqualify white men it should not disqualify black men. We considered that colored men were deeply interested in the country and had at least sense enough to know whether government worked well or not in its more palpable operations, and therefore would probably be safe voters."

On a visit to Washington he came to the attention of Republican legislators who saw in the transplanted Northerner a potential ally, someone who could help protect freedmen's rights as well as the future of the Republican Party in the South. Congressman Butler helped persuade President Grant of the value of placing a man like Akerman in the cabi

net as a show of confidence in and support for all Southern Republicans. Who better than a man with proven loyalty to the South to take the reins of the newly established Justice Department as it faced the politically sensitive dilemma of dealing with the Klan?

Prior to the creation of the Justice Department, the federal government had hired lawyers to argue its cases, a method both expensive and frequently ineffectual. The new department would rely on federal district attorneys as well as the solicitor generalâa new positionâto see that federal law was observed, a timely adjustment to counter Southern lawlessness and the ineffectiveness of local courts there. Akerman identified thoroughly with his mission but "discovered at Washington, even among Republicans," he told Charles Sumner, "a hesitation to exercise the powers to redress wrongs in the states. This surprised me. For unless the people become used to the exercise of these powers now, while the national spirit is still warm with the glow of the late war, there will be an indisposition to exercise them hereafter, and the 'States Rights' spirit may grow troublesome again."

Akerman was by now impatient with his Southern neighbors' continued rejection of the outcome of the war, and he held the deepest contempt for night riding and political violence, which he called "KuKluxery." What especially worried him, and what he feared most Northerners failed to appreciate, was that Klan intimidation often went well beyond night riding. The midnight visit to a freedman's cabin by a handful of local vigilantes could seem almost quaint compared to what the Klan looked like at full strengthâscores of men, some in disguises, some in tattered Confederate gray, raising the dust of a sleepy courthouse town, thoroughly overwhelming its citizens and authorities alike. He also was perhaps the lone high-ranking federal official who knew what it was to live in fear of the Klan, for he had a wife and several children still residing in Georgia.

"One cause of [the] readiness to secede in 1861 was the popular notion that the government at Washington was a distant affair, of very little importance to us," he wrote of his fellow Southerners, emphasizing that the federal response to the Klan must be consistent and thorough. "They have now been taught better. They ought not to be allowed to forget the lesson." He cautioned against any appeasement or "attempt to conciliate by kindness that portion of the Southern people who are still malevolent. They take all kindness on the part of the government as evidence of humility and hence are emboldened to lawlessness by it." Akerman no doubt pleased President Grant with his conviction

that Klan activity should be quelled without sending additional federal troops into the South. The trend had been one of gradual withdrawal, as troop levels across the South fell from twelve thousand in 1868 to six thousand a year later; any new buildup would smack of renewed sectional confrontation. Akerman wanted instead to use the federal courts to pursue Klansmen as vicious criminals, isolating them from Southern society. The legal teeth for such an approach would be provided by pending legislation that would become known as the Ku Klux Klan Act.

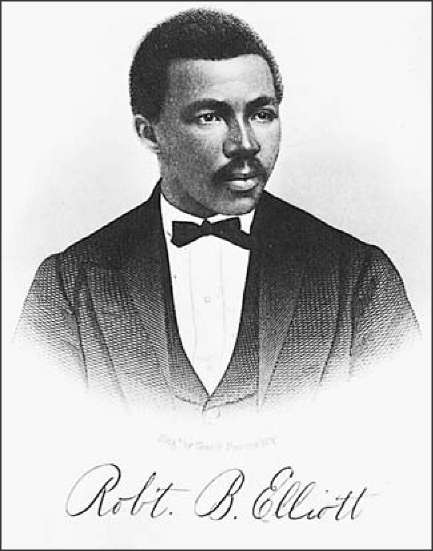

While Joseph Rainey's plea to Congress about the Klan had been both personal and affecting, it was his colleague, twenty-eight-year-old Robert Brown Elliott, a lawyer and a publishing partner to Richard "Daddy" Cain, who offered the most compelling argument for passage of a special Ku Klux Klan bill.

A square-shouldered man of medium height, "black as a highly polished boot," Elliott appeared to journalist Marie Le Baron a "distinguished and agreeable figure" who evinced "no awkward gesture, no obsequious movement to point back to a life of cringing servitude." He claimed that he was born in Boston in August 1842, that his family had then lived briefly in Jamaica, and that as a young man he had been taken to England, where he attended Eton and studied law before returning in 1861 to America, where he eventually enlisted in the Union army. However, Peggy Lamson, a twentieth-century biographer who diligently examined Elliott's past, found no record of his birth in Boston or his schooling in England, nor any evidence that he ever wore a soldier's uniform. What his contemporaries

did

know was that he was articulate, well educated, capable as a printer, and knowledgeable in the practice of law. He was also multilingual, speaking passable French and Spanish as well as English, and was versed in the classics, to which, like his hero Charles Sumner, he often alluded in his orations. More intriguing was the fact that despite so much time abroad, he was conversant with the "political condition of every nook and corner" of South Carolina, "every important person in every county, village, or town...[and] the history of the entire state as it related to politics."

So who was he? A favored slave who had received an education (his African appearance seemed to rule out the likelihood of even partial white parentage), or an opportunistic Englishman who had made his way to the New World? It seems odd that during Elliott's lifetime it was universally accepted that he had lived many years in Jamaica and

England, yet there is no mention in accounts of his numerous speeches that he spoke with a British inflection. It's equally remarkable that for a man who had countless political enemies and who was often under assault from the home-state press, the details he gave of his background seem to go unchallenged.

ROBERT BROWN ELLIOTT

Whatever his origins, Elliott lived well in South Carolina, possessed an extensive library, and married one of the most beautiful quadroons in the state, Grace Lee, who had been a house servant and governess to a prominent white family. Numerous contemporary accounts note her poise and natural elegance as well as Elliott's short temper where his wife's reputation was concerned. Ironically, this most African-looking man had, in addition to his taste for classical scholarship, another trait common to the native-born Southern aristocrat: an easily violated sense of personal honor. In late October 1869 Elliott accused James D. Kavanaugh, a former Union soldier, of writing notes to his wife; confronting the white man outside a government building in Columbia, he shoved him to the ground and repeatedly thrashed him with a whip. Elliott's behavior was not atypical in an age that saw Southern gentlemen routinely cane one another or inflict other "bodily chastisements." What made the assault newsworthy was that, as a black man defending his wife's good name, he was directly challenging the traditional notion that black women were approachable and sexually available to white men, a condition black men had for generations painfully endured. "A Negro from Massachusetts Cowhides a White Carpetbagger" reported the next day's

Charleston Daily News,

slyly inquiring why Yankees kept asserting that blacks were their

equals

when it appeared that Elliott was actually

superior

to Kavanaugh.