Capitol Men (13 page)

Authors: Philip Dray

Many of Washington's "bon tons," as the local black aristocrats were sometimes called, occupied a singular world, some barely familiar with

the inconvenience of prejudice. They acquired property and homes, owned horses and carriages, kept servants, and avoided if possible the company of those of their own color who toted and laundered, scrubbed and hauled, were bawdy and ill-mannered, or worshiped in loud voices at spirited Sunday outdoor "rousers." Some worked for the betterment of the black masses even as they kept the individual representatives of that "unimproved class" at arm's length. The effort of the "betters" to put some distance between themselves and the black hoi polloi was most noticeable on Emancipation Day, the annual freedmen's celebration and the city's biggest outpouring of black pride and celebration, featuring a massive parade, colorful floats, speeches, and daylong parties. Even the egalitarian Frederick Douglass disapproved of the holiday's "tinsel shows [and] straggling processions [that] empty the alleys and dark places of the city into the broad day-light ... thrusting upon public view ... the most unfortunate, unimproved and unprogressive class of the colored people," a display, he feared, that could foster negative stereotypes.

The expanded horizons of citizenship made self-improvement a significant mandate among blacks of all classes. Its most fundamental expression was the widespread desire to gain basic literacy, but it extended to matters of social skill, etiquette, and even personal hygiene. The black press was filled with columns of "do's and dont's" and admonitions to stay clean and tidy, avoid shouting in public, refrain from guffawing or laughing like a horse, and keep the mouth closed so as not to show one's teeth. Later, women journalists such as Memphis's Ida B. Wells would blend political commentary with reminders of the special necessity for black women to live a spotless moral life.

A success story that epitomized the rise of the local black establishment was that of James Wormley, who in 1871 opened the five-story Wormley Hotel at 15th and H Street N.W. Like several other black entrepreneurs in Washington, he had made his reputation as a caterer. The term

catering

in Reconstruction Washington didn't refer primarily to the provision of food and drink for weddings and social functions, but rather to the business of delivering warm meals to the many congressmen, senators, and judges who lived in the city's hotels and rooming houses. It was a profession well suited to black advancement, since it was lucrative but whites tended to shun it because they perceived it as servile. Wormley, who in the 1850s went to London as cook and valet for Reverdy Johnson, President Buchanan's minister to the Court of St. James, pulled off an international culinary coup by bringing along, and

serving to British aristocrats, a large shipment of diamondback terrapins from Chesapeake Bay. While in England he purchased the fine linen, crystal, and china he would ultimately use in his hotel dining room. His attention to detail and the freshness of his ingredientsâhe and his son William kept a farm just outside the cityâmade his establishment, which had an elevator and one of the city's first telephones, a favorite Washington destination. Vice President Schuyler Colfax lived in one of its suites, and Charles Sumner and others were frequent guests.

Reconstruction Washington's most famous social eventâcelebrated for its extravagance as well as its racial inclusivenessâwas the ball held in honor of President Grant's second inaugural in March 1873. Those attending included Louisiana's black governor, P.B.S. Pinchback; South Carolina's congressman Robert Brown Elliott and his wife, Grace; Frederick Douglass; and three thousand other guests, gathered in a specially designed building in Judiciary Square. Grant's first inaugural ball, in 1869, had been something of a bust, poorly managed and plagued by icy cold weather. The 1873 version was similarly troubled by chilly temperatures, which congealed the desserts and forced the guests to waltz in their overcoats, but the mood remained festive. The dining area, about the length of a city block, offered among its various edibles 26,000 oysters, 2,400 quails, 75 roast turkeys, 25 boar's heads, 8,000 sandwiches, 150 cakes, and 24 cases of Prince Albert Crackers, all to be washed down with 300 gallons of punch and an equal quantity of hot coffee. "Praises of the completeness of all the details, and the perfection with which everything moves, are on every tongue," gushed the

New York Times.

General William T. Sherman and other leading military men of the late war, resplendent in their brass and blue, were applauded as they stepped onto the dance floor, but the hit of the evening was a spirited contingent of West Point cadets, some of whom created a delicious stir by dancing with the wives of the black congressmen. Grace Elliott, a visiting Southerner conceded, was "one of the most beautiful and handsomely gowned women at the ball."

Grant's inauguration and the ball were long remembered by those fortunate enough to be in attendance as a unique, glittering moment of black attainment and white broadmindedness. "In the grand procession ... the advance the nation has made under the genius of liberty was epitomized," cheered the

New National Era

. "Colored cadets ... marching side by side with white cadets, colored marshals, colored militia, colored Congressmenâall took part in a ceremony in which only a few short years ago none but white persons were allowed to participate. No

organization military nor civic withdrew from the line because colored citizens participated, no white person left the inaugural ball ... There seemed to be a general acquiescence to the new order of things."

Revels was much in demand upon his entry into Washington's political brotherhood. He at first lived with George T. Downing, the black Rhode Island abolitionist and entrepreneur who ran the Capitol Restaurant on the Hill. A dinner hosted by Downing in Revels's honor featured numerous senators and was "of the most recherché character," where "every honor was paid the distinguished successor of Jefferson Davis ... There were no speeches ... but the company engaged in lively conversation and remained until a late hour listening to words of wisdom from the lips of the sable Senator from Mississippi." In honor of the occasion, Frederick Douglass's new publication offered a lithograph of Revels for sale, an image "equal to a first rate original oil painting [that] would do no discredit to the walls of any parlor in America." While black people were usually depicted in cartoons or works of art "either as apes or as angels," said the

Era,

it was refreshing to see in the image of Revels "the real man, neither flattered by partiality nor distorted by malice or prejudice."

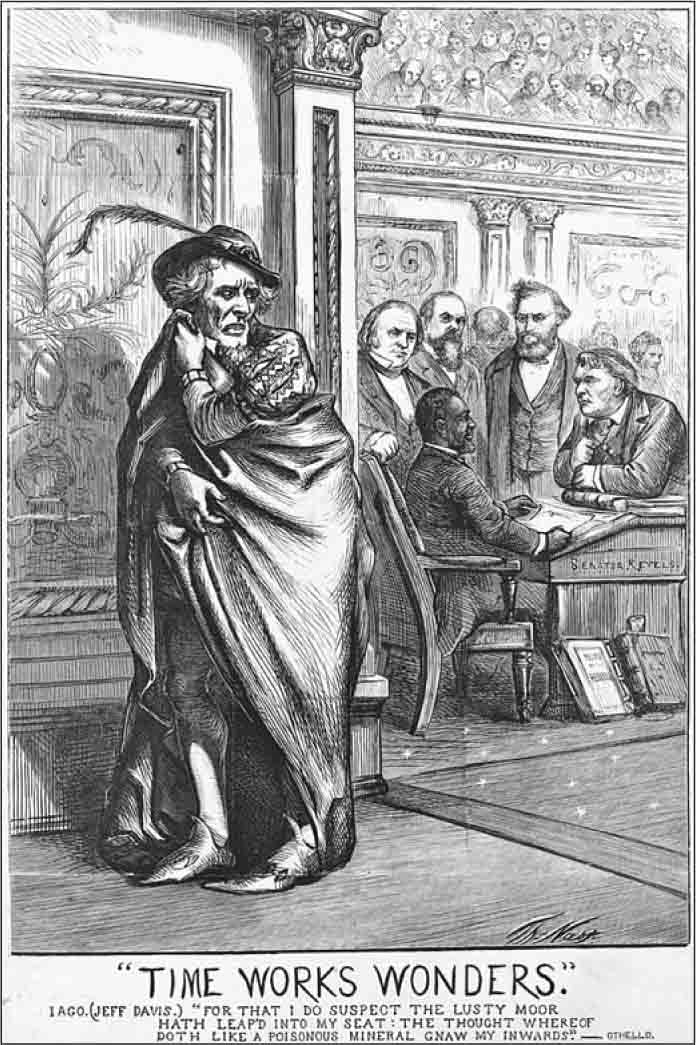

Although there was much talk of how Revels "replaced" Jefferson Davis, technically Davis's seat had expired in the nine years since his departure. But the prospect of the traitorous Davis being upstaged by a loyal black man was too rich an irony to ignore. In a devastating cartoon by Thomas Nast, Davisâas Shakespeare's Iagoâpeers in from behind a curtain as Revels takes the secessionist's former place. "For that I do suspect the lusty Moor hath leap'd into my seat," muses Nast's Davis, "the thought whereof doth like a poisonous mineral gnaw my innards." Nast was merciless toward the former Confederate president. Another cartoon, titled "Why He Cannot Sleep," depicts Davis in bed as Columbia reveals to him the ghosts of numerous rebels, one of whom has crawled next to Davis and points to a bullet hole in the center of his skull.

Humiliating Davis had been an irresistible Northern pastime since his capture in May 1865. President Johnson had accused Davis of complicity in Lincoln's assassination, and a $100,000 bounty was placed on his head. Davis was not involved in Lincoln's murder and in fact disapproved of it, but this was not immediately known in the confusing weeks following the war. Davis, his family, and his entourage were at that time in desperate flight through rural Georgia in an effort to reach the Florida coast and secure passage by boat, possibly to Cuba, when on

May 10, outside Irwinville, Union troops overtook them. Davis, attempting to escape (or give fight, depending on which account one accepts), either accidentally grabbed his wife's raincoat or slipped her shawl over his head, the origin of the durable tale that the chief rebel tried to flee disguised as a woman.

JEFFERSON DAVIS AS IAGO

Davis was kept under lock and key at Fortress Monroe for two years while the government debated what to do with him. Was he a captured enemy leader deserving of official respect or a base traitor ripe for the gallows? (Only one prominent ConfederateâHenry Wirz, commandant of the prison camp at Andersonville, Georgia, where 13,000 federal soldiers diedâwas hanged because of his actions during the war.) The government's indecision and delay favored Davis's cause, thanks in part to the dedicated public relations efforts of his wife, Varina, and their friends. The height of his rehabilitation was the 1866 publication of

The Prison Life of Jefferson Davis

by John J. Craven, Davis's physician, which portrayed Davis as an ill-treated martyr who read the Bible, prayed daily, and saved crumbs of food for a mouse that lived in his cell. His imprisonment ultimately became a political liability for President Johnson, as petitions bearing thousands of signatures demanded Davis's release. (One midwestern businessman offered $30,000 for the right to exhibit the captive, promising to return him in good health.) The predicament worsened when Davis, insisting he was not guilty of anything, refused Johnson's offer of a pardon.

In May 1867, two years after his capture, Davis, looking gaunt and unwell, was released on bail provided by the publisher Horace Greeley, the railroad tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt, and the reformer Gerrit Smith. There was still talk of putting the ex-Confederate president on trial for treason, a course Davis himself was said to welcome, since it would give him a chance to clear his name and defend the Southern cause, but public sentiment, various legal technicalities, and then the impeachment of Johnson himself kept it from ever taking place.

While Republicans took pride in the arrival of Hiram Revels, the Democrats were not about to allow him a free pass. As soon as President Grant signed Mississippi's readmission into the Union (on February 23, 1870) and Senate Republicans moved to have Revels sworn in, the opposition began to forcefully resist seating him, just as the House had done successfully the year before in the case of Louisiana's J. Willis Menard. The apparent winner of a special election held in Louisiana to fill a seat vacated by the death of a sitting congressman, Menard was certified as the new representative by Louisiana's legislature and its youthful Reconstruction governor, Henry Clay Warmoth. But a white candidate, Caleb'S. Hunt, disputed the election results, and in the end neither Menard nor Hunt was seated. Before this rejection, Menard made history by defending his claim on the floor of the House for a quarter of an hour on February 27, 1869âthe first time a black American ever addressed Congress.

The debate over Revels opened when Southerners argued unsuccessfully that the white military governor of Mississippi, the carpetbagger Adelbert Ames, did not possess the authority to certify Revels's election.

But the chief obstacle was constitutional. Democratic critics pointed out that even if Revels (like other blacks) had been made a citizen by the Civil Rights Act of 1866, he had not been a citizen for nine years, a requirement for senators, according to the first article of the Constitution. The Democrats also questioned whether the Founding Fathers had ever intended black people to be citizens, reminding the Senate that in the

Dred Scott

decision of 1857, the Supreme Court had clearly asserted that although free blacks might be citizens of individual states, they (and certainly slaves) were not citizens of the United States. Chief Justice Roger Taney wrote, in his majority opinion, that black people were "so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect."

Republican senators cried foul at such a tactic; James W. Nye of Nevada insisted that "[

Dred Scott

] has been repealed by the mightiest uprising which the world has ever witnessed." Indeed, much of the Republicans' legislative program since the war had aimed to undo the harm of

Dred Scott;

the Civil Rights Act and the Reconstruction amendments struck at the very themes that Taney had handled so poorly. But the Democrats were relentless. Senator Willard Saulsbury of Delaware characterized the Taney court as "giants!âgreat, intellectual, mighty giants, in comparison to whom the dwarfed intellects of the present hour are but pygmies perched on the Alps" and declared the Fourteenth Amendment to be "no more part of the Constitution than anything which you ... might write upon a piece of paper and fling upon the floor." He cleverly asserted that despite the insult rendered by Charles Sumner (who had said "the name of Taney is to be hooted down the page of history") the Republicans obviously

did

accept

Dred Scott,

since they had gone to great lengths to produce the 1866 Civil Rights Bill and pass it over Johnson's vetoâan explicit effort to undo Taney's handiwork. Such determination, said Saulsbury, implied the Republicans' recognition of the legitimacy of Taney ruling and provided "evidence that in your own judgment at the time of [the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1866]...negroes and mulattoes were not citizens." Since only four years, not nine, had passed since 1866, Saulsbury concluded, Hiram Revels could not now be considered an American citizen. "Addressing you not as Republicans, but as revolutionists, there is one extent to which your revolutionary movement has not carried you yet, and that is to make a negro or mulatto eligible to a seat in the Senate of the United States."