Capitol Men (3 page)

Authors: Philip Dray

If federal authorities continued to wrestle with such matters, there was for Robert Smalls little confusion. It had been no secret to him, or most other slaves, that the victory of Abraham Lincoln in the election of 1860, and the outbreak of war itself, held the definite potential for freedom. Looking out on clear evenings from the pilothouse of the

Planter,

Smalls could see the lights of Beaufort and marvel at the fact that his mother and other relations and friends there were already free.

By spring 1862, with the federal lines so close, Smalls and the other slaves on the

Planter

began talking of crossing over, perhaps using the boat itself as a means of deliverance. Any slave caught plotting such an act, let alone carrying it out, would be killed, and Smalls understood that neither his connections to a good Southern family like the McKees nor his usefulness as a ship's pilot would save him. But he agreed with his mates to discuss the notion further and to watch for an opportunity to escape.

They had several advantages. Smalls knew the placement of the Confederate batteries and the location of all the mines in Charleston Harborâhe had helped put them thereâas well as the signals needed to pass by the harbor defenses. He later explained that the scheme for using the boat to escape was partly inspired by a casual remark made by one of his crew that, in height and build, he resembled the ship's white skipper. One afternoon when the whites were elsewhere, the crewman had playfully slapped Captain C. J. Relyea's distinctive straw hat onto Smalls's head and exclaimed, "Boy, you look jes like de captain."

The

Planter

returned to Charleston on May 12 after having spent nearly a week moving guns from Cole's Island to James Island. Smalls suspected that since the boat had not berthed in Charleston for many nights, its white officers would likely choose to spend the night ashore, leaving him in charge. (This violated Confederate naval policyâat least one officer was required to remain with the ship at all timesâbut the rule was often disregarded.) In the afternoon a wagon carrying two hundred pounds of ammunition and four small pieces of artillery arrived at the wharf for transport to Fort Ripley, a newly built harbor fortification. Realizing this cargo would be a substantial prize for the Union forces, Smalls quietly ordered his men to take their time loading it onto the

Planter,

so that the delivery to Fort Ripley would be put off until the next day.

Once the whites had departed, Smalls and his fellow conspirators made their final arrangements, then laid low until about 2

A.M.

, when he ordered the boilers fired. As a precaution, Smalls had told the crew that if a sentry came by, they should complain loudly and bitterly about the early morning departure and curse "the cap'n and his orders." A sentry on the wharf did hear the steamer come to life but later recalled he did not "think it necessary to stop her, presuming that she was but pursuing her usual business."

Smalls had timed their departure so that his ability to impersonate Captain Relyea would work to maximum effect. If they tried to pass Fort Sumter in total darkness, he feared the sentry there might demand to speak with him to ascertain his identity; but Smalls surmised that in the half-light just before dawn, Relyea's profile, his naval jacket, trademark straw hat, and even his characteristic way of pacing the deck, which Smalls had learned to mimic, would suffice to allow the boat to pass without inspection. Having positioned himself in the pilothouse as the vessel reached Fort Sumter, he "stood so that the sentinel could not see

my color" and nonchalantly gave the correct series of short blasts on the ship's steam whistle. After a pause that must have seemed an eternity, the sentinel replied, "Pass the

Planter

..."

Once past Sumter, Smalls at first followed the set route for Confederate vessels departing the harbor, heading southeast in order to hug the coast along Fort Wagner. But he did not complete that final turn. Crying down to the engine room to cram the boilers "with pitch, tar, oil, anything to make a fire seven times heated," Smalls abruptly swung the

Planter

toward the open sea. Confederate signalers atop the shore batteries expressed concern, querying the

Planter

as to why it was heading the wrong way. Had they grasped Smalls's intentions, they might have succeeded in bringing the ship under fire, but with the

Planter

's furnaces roaring, the boat was in moments safely out of range. As the ocean waves crashed over the speeding bow, Smalls removed Relyea's hat and exulted to his companions, "We're all free niggers now!"

They were in fact hardly out of danger. The Union boat crews manning the blockade had sprung to life as the

Planter

approached, worried that the unknown vessel might be a Confederate ram. Smalls, from his bridge, heard drums being beaten in a call to arms. He quickly ordered the Confederate flag hauled down and a white bed sheet hoisted in its stead.

"Ahoy there," a voice from the Union ship

Onward

called out, "what steamer is that? State your business!"

"The

Planter,

out of Charleston," Smalls replied. "Come to join the Union fleet."

A very surprised Captain F. J. Nichols of the

Onward

was the first aboard the Confederate boat, where he was surrounded by Smalls and his band of exuberant runaways. Nichols later reported that he was told by "the very intelligent contraband who was in charge...'I thought the

Planter

might be of some use to Uncle Abe.'"

The next day's notice in the

Charleston Courier

took a less cheery tone. "Our community was intensely agitated Tuesday morning by the intelligence that the steamer

Planter

...had been taken possession by her colored crew, steamed up and boldly run out to the blockaders," the article read. "The news at first was not credited; and it was not until, by the aid of glasses, she was discovered, lying between two Federal frigates, that all doubt on the subject was dispelled." The paper, in its account of "this extraordinary occurrence," noted that one of the Negroes aboard the boat belonged to Mrs. McKee, and reported that it appeared from shore that the Yankees were already stripping the captured ship of its

deck guns. This represented a hurtful loss at a time when the Confederacy was desperate for reliable ordnance, but to the federals, the acquisition of the

Planter's

guns was only a secondary gift. The greater prize was the boat itself, for the Union navy lacked vessels with a shallow draft, able to operate in the channels around the Sea Islands. Equally important, the United States had gained the services of Robert Smalls, whose knowledge of the local waters, as well as his intelligence about the positions of Confederate mines and gun emplacements, would be invaluable.

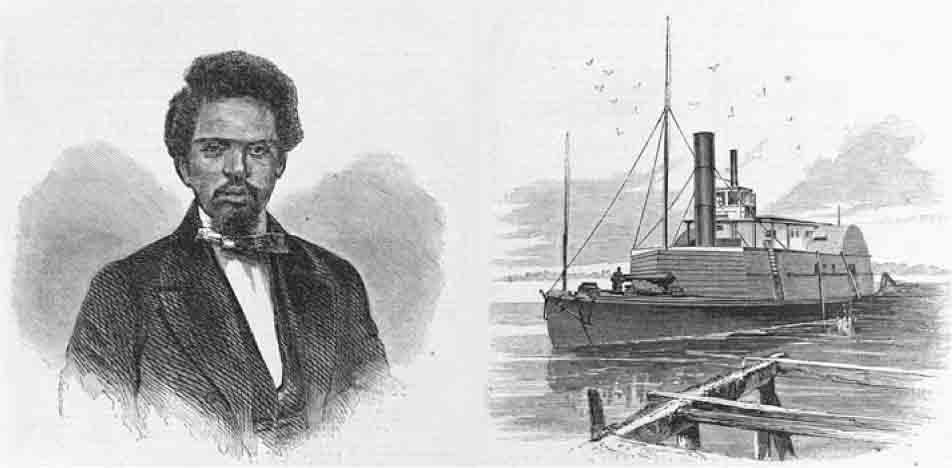

Harper's Weekly

and the

New York Tribune

were among many Northern periodicals to herald the theft of the

Planter; Harper's

ran an illustration of Smalls, terming his feat "one of the most daring and heroic adventures since the war commenced." The blow to the South's pride was commensurate, and its newspapers demanded harsh penalties for the white officers who had allowed slaves to steal a valuable boat. General Robert E. Lee wrote from Richmond that all precautions must be taken to ensure such an avoidable tragedy did not recur. (Captain Relyea and two of his officers were convicted of disobedience in the case but evaded punishment.)

ROBERT SMALLS AND THE

PLANTER

Smalls's daring act not only boosted Northern morale but also represented a decisive victory for his people. At a time when America's leaders could not agree on what to do with blacks freed from bondage by the war, and when even many abolitionists were uncertain about former slaves' potential as independent workers and citizens, the

Planter

's story made a compelling case for their native pluck and resourcefulness.

"What a painful instance we have here of the Negro's inability to take care of himself," deadpanned the

Providence Journal

. "If Smalls had a suitable white overseer, he would never have done this foolish and thoughtless thing. Such fellows need a superior who is familiar with the intentions of divine providence and who could tell them where they were meant to stay."

Smalls's action had an immediate effect on a debate then roiling Washington as to whether blacks emerging from slavery could serve as soldiers in the Union armies. Smalls himself was soon given the chance to advocate for their inclusion.

From the war's beginning, a vocal element in the North had argued for emancipating the slaves in order to ground the nation's conflict in a moral cause, demoralize the South, and possibly create a new source of troops. But President Abraham Lincoln hesitated. To cast the fight as a war of emancipation, rather than one that solely aimed to reunite the Union, would, he feared, alienate the border states and push them into the Confederacy. "My paramount object in this struggle," Lincoln proclaimed, "is to save the Union. If I could save the Union without freeing

any

slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing

all

the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would do that." It was thought by many, including Lincoln, that an emigration program to resettle the slaves would be required if four million blacks were suddenly to become free; until early 1863, the government even entertained the hope that the South, or parts thereof, might return to the Union voluntarily, perhaps with some program of gradual emancipation and compensation to slaveholders for their loss.

Curiously, the militarization of blacks was originally a Southern strategy; Negro regiments were formed in Georgia, Tennessee, and Louisiana in the early months of the war. The Confederacy's battlefield successes in 1861 and 1862, however, convinced its leaders that there was no need to use black troops; the practice was repugnant to most Southerners anyway, and so the men were largely sent home. (Some, like Josiah T. Walls, later a black congressman from Florida, eventually crossed over to the Union forces, becoming one of the few Americans to fight on both sides in the war.) The South did not revisit the idea until early 1865 when, in desperate straits, the Congress of the Confederate States agreed to let General Lee seek the enlistment of black troops; within weeks, however, the rebel cause was lost.

Union policies were ultimately pushed toward resolution by the slaves

themselves, for the eagerness of black refugees to flee their masters was evident wherever federal troops advanced. "War has not been waged against slavery," Secretary of State William H. Seward wrote, "yet the army acts ... as an emancipating crusade." In May 1861 a weak compromise on the issue was reached in Virginia, where the Union general Benjamin F. Butler, commander of Union forces at Fortress Monroe, was confronted with three runaway slaves seeking his protection. One, George Scott, told Butler that the Confederates had put him and other slaves to work building gun emplacements and ramparts. At Butler's behest, Scott guided a Union scouting mission to the enemy's lines to verify this claim. When, soon after, a Confederate officer came to Butler's headquarters under a flag of truce to claim Scott and the other two runaways, Butler refused to release them. In moving his army through Maryland, he had promised state officials he would not act to incite slaves to insurrection. Now, however, he couldn't help but wonder why he should return slaves known to be assisting the Confederate war effort. At the suggestion of one of his aides, Butler resolved the situation by declaring Scott and the others "contraband of war."

The designation was much discussed in Washington. The term "contraband" implied ownership and conveniently did not call into question the legal basis of slavery. It fit nicely within the strictures of the First Confiscation Act, passed in August 1861, which allowed federal troops to take command of any property being used to abet or promote the Southern rebellion, including slaves laboring for the Confederate military effort. Officially the concept of confiscation was to go no further. When the Union general John C. Fremont declared martial law in Missouri in late summer 1861 and pronounced the local slaves free, Lincoln immediately rescinded the order. But even though the president had canceled Fremont's action, and members of his cabinet continued to parse the meaning of Butler's "contraband," the significance for black people still in bondage was clear: they would not be returned to their owners once they reached federal lines.

The pressure on Washington increased in spring 1862 when the Union general David Hunter, relieving General William T. Sherman as commander of the Sea Islands, announced his decision to turn the numerous contrabands in his charge into soldiers. Hunter, upon taking over Sherman's command, had wasted little time in seizing Fort Pulaski, a strategic post at the sea approach to Savannah, and he was eager for additional conquests. He had written to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton of his special desire to retake Fort Sumter for the Union cause. With

such ambitions, it was natural that he saw the thousands of ex-slaves gathering at Port Royal as potential troops and hoped that an earlier order from the former secretary of war, Simon Cameron, authorizing Sherman to employ "loyal persons," might effectively cover the action he contemplated. "Please let me have my own way on the subject of slavery," he asked of Stanton as early as January. "The administration will not be responsible. I alone will bear the blame; you can censure me, arrest me, dismiss me, hang me if you will, but permit me to make my mark in such a way as to be remembered by friend and foe."