Capitol Men (2 page)

Authors: Philip Dray

The "glorious failure," as Reconstruction is sometimes termedâpolitically turbulent, riven by corruption, often exceedingly violentâcan be a disquieting saga to get to know: a lost opportunity, certainly, and in many ways a shameful time in our nation's history. Yet it is also a powerful story of idealism and moral conflict that belongs only to us and whose arc is as beautiful as it is tragic. At its core is something of undeniable valueâthe courage of black and white Americans who together aspired to right the country's greatest wrong. That this coalition has always been tentative in our history, or that the grand experiment of Reconstruction failed or was premature, cannot diminish the effort's genius or inherent nobility.

BOAT THIEF

A

PERSON GAZING OUT

across Charleston Harbor in the predawn quiet of May 13, 1862, would probably have found it hard to believe that the Civil War had begun at this very spot only a year before, with the thunderous shelling of the federal garrison at Fort Sumter. Certainly the signs of war remained, most noticeably the rebel cannon that guarded the harbor and pointed seaward from numerous shore ramparts, their sights fixed on the ships of the Union blockade positioned three miles offshore. But all was now perfectly still, and the only discernible movement took place aboard the

Planter,

a small Confederate transport that appeared to be preparing to depart.

Hours before, the

Planters

white captain, C. J. Relyea, and his officers had gone ashore for the night, leaving the vessel in the hands of its mulatto pilot, Robert Smalls, and creating the very opportunity that Smalls and his fellow slave crewmen had been waiting for. Having discussed in detail their plan to use the boat to make a break for the Union blockade, they stealthily began their chores between 1 and 3

A.M.

, maneuvering the

Planter

to a nearby pier to pick up Smalls's wife and two children as well as four other black women, a child, and three other men. Because the punishment for what they were about to do would surely be death, Smalls had told the others that if caught, they would not surrender but would destroy the boat, along with themselves and all the Confederate guns and ammunition it carried. Two of the crewmen had heard Smalls's warning and elected to stay behind, disembarking as the new passengers came aboard. At about 3

A.M.

final farewells were whispered and the

Planter

eased back from the pier.

Despite the hour and the darkness, the city defenses were on alert against Union raiding or reconnaissance parties. Charleston, known for

its cultured antebellum society and its leadership in the Southern secessionist movement, formed the emotional and political heart of the Confederacy; it was also a strategic Atlantic port, and its defenders knew that the federals, having been driven from Fort Sumter in the war's first action, dreamed of recapturing it. To escape the harbor, the

Planter

would have to pass directly under the guns of several formidable batteries, including those of Fort Sumter itself, which was now in Confederate hands. The fort, set strategically in the middle of the harbor's entrance, was a manmade island, a pentagon-shaped fortress with walls sixty feet high and six feet thick and guns protruding from all sides, emanating "an aura of doom and menace."

As the

Planter

moved toward the gauntlet, some on board suggested racing past the rebel installations, but Smalls reminded them that such a panicky move would likely be fatal: their best and only hope was to pretend nothing was out of the ordinary. He was banking on the likelihood that sleepy rebel watchmen would not be suspicious of a work ship nosing its way out of the harbor before dawn, nor would they be inclined to imagine that slaves were stealing it.

With this audacious act, Robert Smalls was exploiting a lifetime of trust and privilege placed in him by his white mastersâfirst as a favored house servant, then as a semi-independent laborer and skilled sailor. Born on the South Carolina Sea Islands in April 1839, he was the son of Lydia, a slave woman, and either the Charleston merchant Moses Goldsmith or John McKee, who was Lydia's master. As a girl, Lydia lived and worked on a McKee plantation on Ladies Island, adjacent to the Sea Island town of Beaufort. Because of the dread fear of malaria, the wealthy planters of Beaufort visited their landholdings on the nearby islands only occasionally. One Christmas, when Mr. and Mrs. McKee toured the plantation, distributing oranges and other small gifts to the slaves, Lydia was precocious enough to compliment her mistress on the dress she was wearing. Mrs. McKee, charmed by the youngster's remark, asked her age. "I was born the year George Washington got president," Lydia replied. When John McKee next returned to the plantation, he asked after "the little girl who knew about George Washington," and took Lydia with him back to Beaufort to serve as a housemaid.

Beaufort was the capital of Port Royal Island, which, with the nearby islands of Ladies and St. Helena's, held a prominent position in the lush coastal region Carolinians call the low country. With its endless bays, rivers, tidal estuaries, and broad wetlands, its vast open distances,

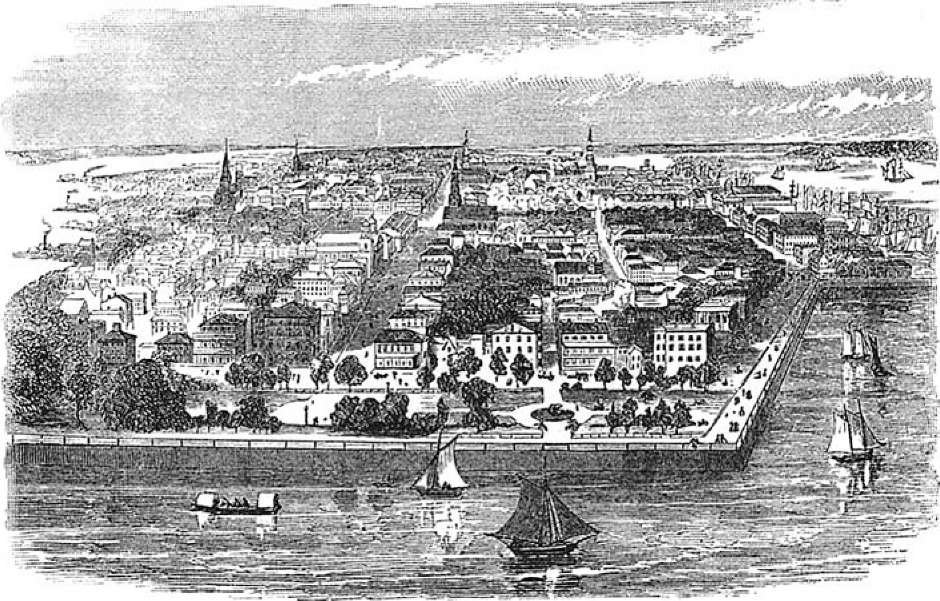

swarms of shore birds and marsh cranes, and the ancient live oak trees whose "fingers" almost scraped the ground, it seemed a faraway, otherworldly place. In the seventeenth century it had become a rice-growing mecca after the planters selectively imported West African slaves who had knowledge of rice cultivation; these slaves introduced the complex methods of irrigation, seeding, and flood control that made the Carolina rice plantations profitable. By 1860, the South was exporting 182 million pounds of rice per year, two thirds of it from South Carolina, and the crop's success had helped make both Beaufort and Charleston prosperous towns, with grand white-columned mansions, high-steepled churches, and the Southeast's most cosmopolitan society.

Robert Smalls grew up in the McKee household, childhood playmate to his master, Henry McKee, who was likely his half brother, while his mother, Lydia, served the McKee family. So comfortable was the arrangement that after several years Lydia began to worry that her bright, energetic son might come to difficulty in the town someday by failing to understand his true status. To forestall such a problem, she took the unusual step of forcing Robert to watch the slave auctions and whippings at the arsenal building on Beaufort's Craven Street, reminding him that only good fortune kept him from sharing the fate of the wretched people he saw there. Her strategy was not, however, entirely successful, for at age twelve Robert was caught defying the local slave curfew and soon after told his mother that he had listened with interest as another slave read a passage from a book by the abolitionist Frederick Douglassâthe kind of proscribed acts she feared could get him cast out of the McKees' Beaufort house to toil on the family's island plantations, or worse. South Carolina rice plantations by no means presented the worst work conditions. Because the owners relied greatly on African ingenuity, the slaves had managed to negotiate somewhat more favorable work conditions than prevailed elsewhere in the South. Rather than labor from sunup to sundown, they were expected each day to execute assigned tasks; once they had completed them, they were free to hunt, fish, or cultivate their own crops. Still, work in the fields was strenuous; slaves labored long hours in knee-deep water, and there was an ever-present danger of snakes, insects, and malariaâthe very risks that kept the white planters on Beaufort's higher ground. Lydia wished to spare Robert from such a fate and finally appealed to the McKees to send her rambunctious son to Charleston, where the family maintained another home and where she believed Robert's insubordinate streak would be less apparent.

In contrast to Beaufort, Charleston was a metropolis, a place of hubbub, splendor, and riches. Carriages with liveried servants traversed the palm-tree-lined boulevards and waited under the lamplights of impeccable mansions and hotels. Gentlemen strolled the Battery, talking politics and business, as ladies in crinoline window-shopped along fashionable King Street. Beyond the busy central market, with its fish stalls, vegetables, spices, and colorful rows of textiles, hundreds of large-masted ships lined the waterfront, taking on pallets of rice, tobacco, and other foreign-going cargo.

CHARLESTON BATTERY DURING THE MID-NINETEENTH CENTURY

The city ran on the energy of thousands of slaves like Robert Smalls, as well as a substantial community of free blacks, many of whom were small tradesmen or skilled artisans such as roofers or carpenters. Even free blacks, however, were made to wear identity tags and have a white "guardian," for the ongoing political agitation over slavery in the 1840s and 1850s had made local whites jittery. South Carolina, and Charleston in particular, had experienced at least two significant slave rebellionsâthe Stono Rebellion of 1739, which broke out only twenty miles from the city, and the aborted Denmark Vesey uprising of 1822. In the Stono disturbance, one hundred slaves trying to escape to Florida ravaged plantations and killed two dozen whites before encountering the militia, which slaughtered them and placed their severed heads on posts by the roadside. In response to the affair, the colonial legislature enacted the

Negro Act of 1740, severely restricting slave behavior and mobility. The Vesey rebellion, planned for July 14, Bastille Day, 1822, was the brainchild of a fifty-five-year-old carpenter, Denmark Vesey, a former slave who had purchased his own freedom. Before Vesey could strike, however, two house slaves alerted the authorities, and he, along with several comrades, was arrested and put to death. The threat of slaves' being fired to revolt by conspiracies led by free Negroes remained very real in the minds of white Carolinians, perhaps because after 1820 blacks began to outnumber whites in the state, and free blacks, because of their greater worldliness, were believed to be more likely to stir the embers of discontent.

Although slave-control measures were carefully observed in Charleston as secession and war loomed, Robert Smalls managed to win increased trust and freedom from his white family. He arranged with the McKees to hire himself out as a day laborer and later as a town lamplighter, paying fifteen dollars a month to his owner. In 1856, at age seventeen, he married a thirty-one-year-old slave named Hannah Jones, who worked as a hotel maid. From his modest earnings, Smalls began saving to buy his own and his wife's freedom, as well as that of their daughter, Elizabeth, who was born in 1858. His fortunes brightened considerably when he attained work in the town's maritime trades. From his boyhood in coastal Beaufort he was already familiar with boats and their operation, and he proved a quick study, learning the myriad channels, currents, and shoals of Charleston Harbor. John Simmons, a white rigger and sail maker who took a liking to the young man, mentored him in shipboard work and navigation, and by 1861 Smalls was the wheelman (blacks were not allowed to hold the title of pilot) aboard the

Planter,

a cotton-hauling steamer plying the rivers and inlets between Charleston and the Sea Islands. One hundred fifty feet in length and able to carry fourteen hundred bales, it was, because of its four-foot draft, ideal for maneuvering in the shallow coastal waterways. When war broke out, the boat was quickly commissioned by the Confederacy. Guns were installed on its foredeck and afterdeck, and it was immediately put to use ferrying troops, laying mines, and servicing the work crews building the harbor's fortifications.

Smalls's travels at the helm of the

Planter

frequently brought him into the vicinity of his old home at Beaufort, although after fall 1861 no Confederate vessel could approach the place. On November 7, Union naval forces seeking a Southern anchorage for their blockade had bombarded and then invaded the Sea Islands, one of the first portions of the Confederacy to be conquered by federal troops. The South chose not to defend the outlying region, and local plantation owners fled the arriving Union forces, leaving behind their crops, stately homes, and as many as ten thousand slaves.

The Union toehold on the Sea Islands was of great military value, but the area became another kind of beachhead the following spring, with the arrival of two shiploads of Northern abolitionists. These missionaries, men and women from Boston, Philadelphia, and New York, perceived in the abandonment of the blacks of the coastal islands an unprecedented opportunity to demonstrate that, with the proper guidance, former slaves could exercise the virtues of citizenship and free labor. "The Port Royal Experiment," as it became known, was meant to prove the adaptability of free blacks, their eagerness to be educated, and their viability as wage laborers, so as to ease Northern concerns about emancipation. The endeavor proved more complex than anticipated. Though the departed slaveholders were not missed, their sudden exit was wrenching to the social hierarchy of the islands and raised difficult questions: how to restart the islands' agricultural economy, bring in crops, open schools, and decide whether the former slaves would own land or what civil rights they might enjoy. Indeed, events in the Sea Islands had raced well ahead of the formulation of the federal government's own policy toward slaves liberated from their masters by advancing Union armies: were the slaves to be regarded as other people's property or as free human beings?