Capitol Men (5 page)

Authors: Philip Dray

The South thrilled to the victory. A year before at Hampton Roads, in March 1862, the fabled shooting match between the federal ironclad

Monitor

and its Southern counterpart, the

Merrimac,

had ended in a draw, but the repulsion of Union ironclads at Charleston demonstrated that the newfangled boats could be defeated by shore defenses and that the city could withstand an attack from the sea.

Later that year, Smalls was caught in another bloody scrape in the mouth of the Stono River at Folly Island Creek, this time piloting the

Planter.

Whenever Union vessels crept into the watery interior of coastal South Carolina, they risked a loss of maneuverability and the threat of taking close bombardment or sniper fire from shore. The Confederates, trapping Smalls's ship in a narrow part of the river and recognizing it as a stolen prize, resolved to recapture or destroy it, hemming the

Planter

in with an artillery crossfire that shredded the upper part of the wooden boat. When the captain, in the heat of battle, ordered Smalls to ground the vessel and surrender, Smalls emphatically declined. "Not by a damned sight will I beach this boat for you!" he shouted, warning that as far as the rebels were concerned, he and the crewmen were all runaway slaves, and that "No quarter will be shown us!" At that point, according to a later congressional report, "Captain Nickerson became demoralized, and left the pilot-house and secured himself in the coal-bunker." Smalls took control, somehow managing to steer the

Planter

out of range of the Southern guns. Nickerson was dishonorably discharged for his performance, and Smalls, cited for his coolness and bravery under fire, was made the boat's captain.

In the spring of 1864 he was ordered to sail the

Planter

to a shipyard in Philadelphia for repairs; when the work on the boat stretched from weeks into months, Smalls made himself at home in the northern city. Charlotte Forten, a black Philadelphian working as a teacher in the Sea Islands, had written letters of introduction for him to the city's substantial abolitionist community. Smalls busied himself by monitoring work on the

Planter

and raising money to assist the freedmen at Port Royal.

One day in December, Smalls and a black acquaintance were walking back to town from the shipyard when, to escape a sudden downpour, they boarded an empty streetcar. A few minutes later two white men got on, and the conductor told the blacks to leave their seats and go stand on the car's rear platform. Smalls refused. When the conductor insisted, he and his companion got off the car. Smalls was inclined to forget the incident, but the local press learned of it and denounced the fact that "a war hero who had run a rebel vessel out of Charleston and given it to

the Union fleet ... was recently put out of a Thirteenth Street car." Broadsides went up, and a committee of Quakers announced a boycott of the streetcars, vowing to no longer allow a practice by which decent "colored men, women, and children are refused admittance to the cars," while "the worst class of whites may ride." At a spirited mass meeting, concerned Philadelphians were addressed by local luminaries including financier Jay Cooke and locomotive manufacturer Matthias W. Baldwin. In the face of such aroused sentiment, the city's streetcar lines capitulated, the protest helping to inspire the state legislature to ultimately ban discrimination in public transportation throughout Pennsylvania.

That same year Smalls went to Baltimore to join a delegation of black South Carolinians at the Republican National Convention. The group was neither seated nor recognized by the chair, but they made history by formally petitioning the party to include black enfranchisement in its platform. At the time, with emancipation itself a recent development, the request by Smalls and his colleagues for the vote was not likely to get a hearing, even if their presence had been formally acknowledged; however, it was said that the black delegation from the secessionist state of South Carolina was the convention's chief curiosity.

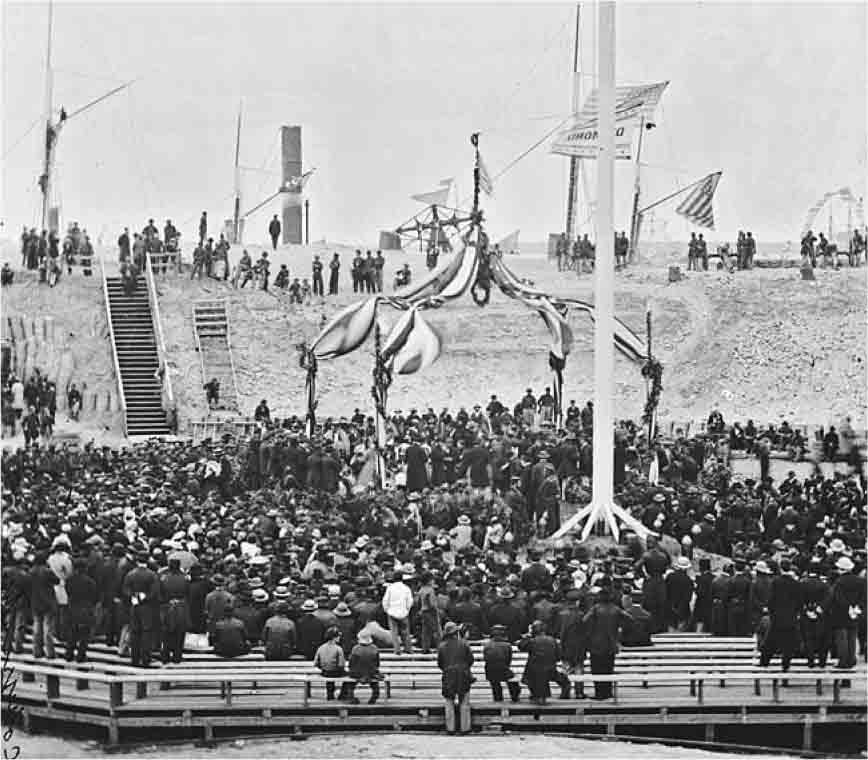

At war's end, Smalls had a place of prominence at the April 14, 1865, celebration in Charleston, marking the anniversary of the firing on Fort Sumter. The ceremonial centerpiece of the day-long event was the hoisting of the Stars and Stripes over the fort by Major General Robert Anderson, the Union officer who had been forced to surrender it in 1861. The Carolina spring day was by all accounts most accommodating, the air "spiced with the aroma of flowers and freighted with the melody of birds, all guiltless of secession, and warbling their welcome." Men, women, and children filled the sidewalks and plazas, waving tiny flags and trying to catch a glimpse of the celebration in the harbor, where hundreds of festooned boats sounded their horns and bells and dispatched fireworks into the sky. On cue, as the American flag rose to its perch above the fort, all the guns in the harbor and those on shore fired a deafening salute.

The abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Phillips, and Henry Ward Beecher were among those who had traveled from Boston and New York to witness the ceremony. Garrison was the editor of the

Liberator,

the nation's most ardent abolitionist publication, and a founder, along with his fellow Bostonian Phillips, of the influential American Anti-Slavery Society. Beecher, the brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of

Uncle Tom's Cabin,

occupied the most famous pulpit in

the country at Brooklyn's Plymouth Church. This was a day of tremendous vindication for these men and their principled fight against slavery. The abolitionists had been abused for three decades, criticized as hateful agitators, and worse; Garrison had been stripped of his clothes by a Boston mob and almost hanged; Phillips had nearly been killed at a public meeting in Cincinnati by a boulder hurled down from a balcony.

THE RAISING OF THE FLAG AT FORT SUMTER

The freed people of Charleston rewarded their travails with a warm welcome. At a mass rally in Citadel Square, the diminutive Garrison was hoisted up into the air to seemingly float on a sea of smiling black faces. In a formal presentation, a speaker assured him that the "pulsations" of the hearts of the black people gathered "are unimaginable. The greeting they would give you, sir, it is almost impossible for me to express; but simply, sir, we welcome and look upon you as our savior." Garrison, equally moved, replied,

It is not on account of your complexion or race ... that I espoused your cause, but because you were the children of a common Father,

created in the same divine image, having the same inalienable rights, and as much entitled to liberty as the proudest slaveholder that ever walked the earth ... While God gives me reason and strength, I shall demand for you everything I claim for the whitest of the white in this country.

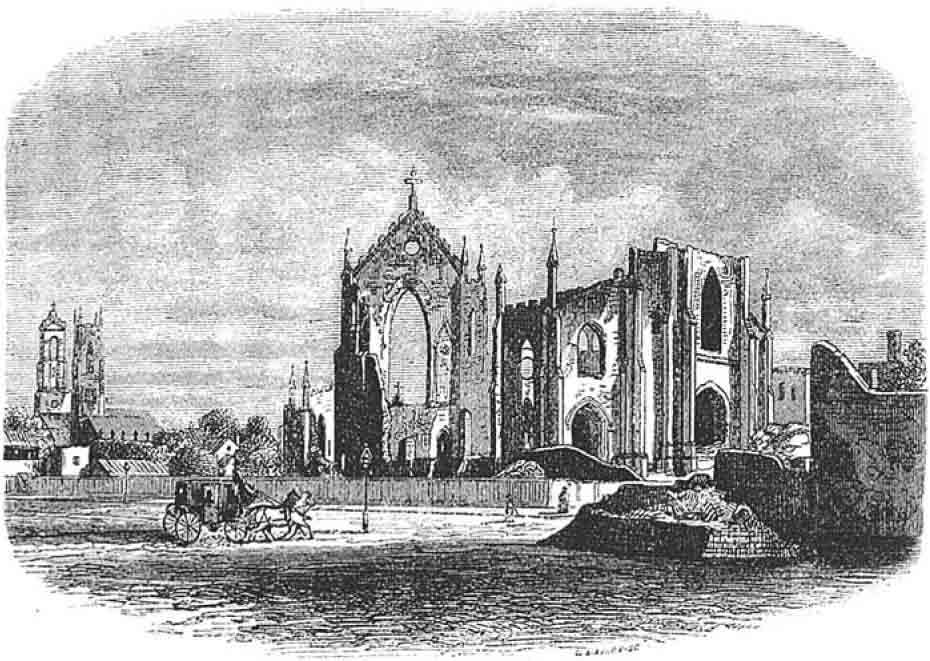

THE RUINS OF CHARLESTON

Both Robert Smalls and his now equally famous boat were also objects of interest to the crowd along the waterfront; Smalls posed gallantly atop the

Planter's

wheelhouse as visitors swarmed over its decks. An American flag was run up the boat's rigging to coincide with the flag raising at Sumter, and as it inched its way to the top, the crowd on the decks below followed its progress with a mounting cheer, until the pennant finally attained the pinnacle, to great applause. "Tears of gladness filled every eye," it was said, "and flowed down cheeks unused to weeping." Even Smalls succumbed to the moment, clumsily backing the

Planter

into another ship loaded with Union dignitaries.

The splendor of the April 14 jubilee in Charleston would glitter all the more in the memory of those who had attended because of the grim event that occurred that very night in Washington: the assassination of President Lincoln at Ford's Theatre. While it was not entirely clear what

steps Lincoln would have taken to reintegrate the South into the Union, his sudden disappearance at a moment of such profound need could only deepen the country's uncertainty. Immense challenges lay ahead, nowhere more visibly than in South Carolina. Of 146,000 white males residing in South Carolina in 1860, 40,000 had been killed or seriously wounded in the war. Charleston itself, South Carolina's chief commercial port, had endured heavy Union naval shelling; of its five thousand houses, fifteen hundred had been destroyed and many others badly damaged. Much business property had been confiscated or was now worthless. "Of all the states overwhelmed by the rebellion, none lies so terribly mangled and so utterly exhausted as its prime mover, South Carolina," observed the

New York Times,

reminding readers that South Carolina was the birthplace of secession and that "its people have been longer and more virulently alienated from the National Government than those of any other state."

Perhaps of even deeper significance than the physical damage was the sudden shift in the legal status of the bulk of South Carolina's residents: approximately 400,000 slaves, contrasted with a white population of less than 300,000, were now free. Politically, as well as socially, such demographics represented seismic change, auguring a future that few could imagine. Robert Smalls was destined to play a central role in this unprecedented transition, which was already being referred to by the not-yet-familiar term "Reconstruction."

A NEW KIND OF NATION

V

ICE PRESIDENT ANDREW JOHNSON

of Tennessee, who assumed the presidency upon Lincoln's death, was a man of humble origins, a former small-town tailor turned politician and U.S. senator who was added to Lincoln's ticket in 1864 to help the administration reach out to Southerners after the war. He held the South's wealthy planter class responsible for secession and initially viewed the postwar period as a time when

his people

âsmall farmers, workers, artisans, and merchantsâmight earn a greater share of the region's leadership. But though he was loyal to the Union and accepted emancipation, the new president differed markedly from men like Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts and Congressman Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, Republicans known as Radicals for their strong views. They saw the South as a conquered foe and called for far-reaching changes in its society and harsh measures for dealing with leading Confederates.

Given that the country was emerging from the trauma of a devastating civil war, the ascent of a man like Johnson after a genial intellect like Lincoln struck the Radicals as tragically unfortunate, for in personal style the new chief executive was a stubborn loner never adept at conciliatory politics. When the need for national healing and inspired leadership could not have been more acute, America was bequeathed not a Washington or a Jefferson, but a man who was

not supposed to be president.

Even if questions about his character had not arisen, Johnson's reading of the times was to prove errant, and events would soon conspire to make his policies appear inadequate. Trying but failing to grasp the country's mood after four years of strife, he took actions that revealed again and again how hungry the nation was for the kind of leadership

he could not deliverâleadership that would project compassion for the freedmen, toughness toward the ex-rebels, and a compelling vision of how the Union might be reestablished. The Radical-led Congress soon became convinced that it, not the president, bore the responsibility for shaping Reconstruction, and its members challenged Johnson at every turn. They overrode his vetoes and passed specific legislation, the Tenure of Office Act, to keep him from forcing from his cabinet those members sympathetic to Congress's views; the act proved a fatal trap for the president; his violation of it in 1868 led to his impeachment.

Johnson had been under a cloud ever since he was sworn in as vice president in March 1864, when he had appeared inebriated at the ceremony. His defenders said that he had been feeling unwell and had swallowed a few glasses of brandy as a pick-me-up. Lincoln, who had heard stories of this intemperance when Johnson served in the Senate, had taken the precaution of sending an aide to Nashville to check up on him before selecting him as his running mate. "I have known Andy Johnson for many years," the president said after the swearing-in. "He made a bad slip the other day, but you need not be scared. Andy ain't a drunkard." Yet despite Lincoln's confidence, Johnson's lack of fitness for high office was a concern in Washington even before he assumed the mantle of the presidency.