Capitol Men (33 page)

Authors: Philip Dray

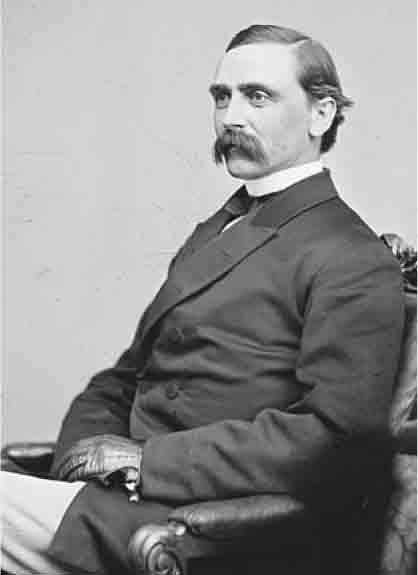

ADELBERT AMES

In 1867 he received his first lesson in the peculiarities of Southern justice when not a single witness could be coaxed to testify before a military court that he convened to prosecute a lynch mob, forcing the case to be abandoned. Then, in 1869, after Ames was appointed military governor of Mississippi, the native spirit struck closer to home. To the position of provisional mayor of Jackson he had appointed Lieutenant Colonel Joseph G. Crane, the tall, likable son of a longtime Ohio congressman. Crane, in the course of his duties in recovering overdue taxes, ordered seized and sold at public auction a piano belonging to Edward M. Yerger, the eccentric scion of a once-prominent Mississippi family. Yerger was away in Memphis when notice of the piano's sale was posted; upon his return he was livid and sent several notes to Crane, demanding satisfaction. A go-between who delivered one of the missives warned Crane that Yerger's "passions were greatly intensified by liquor."

When Yerger finally caught up with the mayor, Crane was at the corner of State and Capitol Streets, one of the town's main intersections, inspecting a sidewalk said to be in need of repair. "Angry words" were heard by several witnesses as Yerger confronted the young Northerner over the "theft" of the piano. When Crane tried to calm his antagonist, Yerger proclaimed him a "God damned cowardly puppy," to which Crane replied, "I do not want to have anything to do with you, except officially," and, making a gesture with his hand, turned to walk away. Yerger, infuriated by the dismissal, struck at Crane's hand; the mayor replied by bringing his cane down on his attacker's neck; Yerger then drew a knife and plunged it into Crane's side, killing him.

The mayor's wife, learning of a commotion involving her husband, rushed to the scene, where a crowd had formed. Pushing others aside, she threw herself on the lifeless body and, hysterical, demanded that he speak, clinging to him for several minutes until her own clothes were soaked with blood. She "was borne from the spot almost a maniac," the next day's paper reported, "amidst the sympathy of the entire gathered population."

At court-martial Yerger's relatives conceded that the killer, whose family nickname was "Prince Edward," was an unbalanced personality, a rabid secessionist who "went into ecstasies" over Lincoln's assassination. They nonetheless challenged the right of a military court to try their kinsman. Ultimately the U.S. Supreme Court ordered him released to the civil authoritiesâthe first time in Reconstruction that the high court had curbed the powers of the federal government in the South. His lawyer then managed to convince a civilian court that a second trial would constitute double jeopardy, so Edward Yerger, to the dismay of Crane's family, Governor Ames, and many others, went free, eventually leaving the state.

Incidents such as Crane's murder, and reports of abuses of the freedmen, had a radicalizing effect upon Ames, transforming him gradually from a bureaucrat of the federal occupation into an indignant advocate committed to upholding the law and defending black people's rights. In 1869 he oversaw the first free election for governor, in which former-Confederate-turned-Republican James Lusk Alcorn was elected. Alcorn, one of Mississippi's leading men of property, promised his constituents a "harnessed revolution" that would offer blacks opportunity even as it retained white authority. To be safe, however, Ames disqualified other officeholders he thought insufficiently repentant and put solid Republi

cans in their places. "The contest [here] is not between two established parties ... but between loyal men and a class of men who are disloyal," Ames explained, when some in Washington questioned the move. "The war still exists in a very important phase here." The following year, as Republicans, including many black representatives, moved into the state legislature, they repaid Ames's devotion by electing him U.S. senator.

As a Northern white official who had seen the mounting Southern resistance firsthand, Ames in Washington became an influential advocate for the freedmen's security. But by 1871 Alcorn had joined him in the Senate, where the two broke over the Ku Klux Klan Act. Ames challenged Alcorn's claims that Mississippi by itself could tamp down the Klan, citing the Meridian riot and the fact that more than two dozen black schools and churches had been torched recently and more than sixty freedmen killed, with no significant action taken by the state to prosecute such crimes. Eventually, in 1873, both Alcorn and Ames re-signed their Senate seats to vie for the Republican nomination for governor of Mississippi, a job they knew would be far more central to the state's future than representing it in the far-off capital.

Back in Mississippi, Alcorn immediately stepped into political quicksand, angering his white constituents by appealing to black voters with promises of equal treatment and seating on the railroads, a vow that, to whites, reeked of "social equality," though for most blacks the promise had little credibility. Because of Alcorn's miscues and a large black voter turnout, Ames won the election easily. Also of help was his developing skill as a political stump speaker. In the nineteenth century perhaps no accomplishment, outside of military valor, was more respected than public oratory, and the buttoned-down officer from Maine took immense pleasure in his newfound ability to hold crowds of Mississippi blacks and whites with his words. As he laid out his appeal for unity and progress, a real depth of feeling for the people of his adopted state seemed to inspire him and to grant his thoughts eloquence.

Blanche Butler was one of Washington's most sought-after belles when Adelbert Ames courted and married her in the early 1870s. Known for her striking appearance as well as her artistic flair and independent nature, she had been the subject of a series of photographs taken by the famous Matthew Brady and exhibited in his Washington gallery. When in 1873 Adelbert Ames decided to abandon the capital to return to Mississippi, she accompanied him, if a bit reluctantly, for she was the daughter

of one of the most despised men in the South, the Massachusetts congressman Benjamin F. Butler, known as "Beast Butler" for his infamous stint as the wartime military governor of New Orleans.

The short, walleyed General Butler, who had introduced the term

contraband

to describe fleeing slaves, was dispatched by President Lincoln to oversee New Orleans after the city was taken by Union forces in spring 1862. Finding the place conquered but its people defiant, Butler responded by seizing control of the local press, arresting those openly disloyal to the Union, and using the recently legislated Confiscation Acts to attach the holdings of New Orleans households owned by absent Confederates. He also ordered the public hanging of a youth named Billy Mumford, who had climbed onto the roof of the U.S. mint to remove the American flag as federal troops arrived in the city. For allegedly pilfering silverware and fine china from elite residences, or allowing his officers to do so, Butler earned the nicknames "Silver Spoon" and "Spoon-Thief." But his action that most infuriated Southern whites was General Orders Number 28, the so-called Woman Order, which labeled as a prostitute any female who disrespected occupying Union troops. Local women were said to have insulted federal officers and even spit at their feet; one had been caught mocking the funeral cortege of a fallen Union soldier. Though Butler understood that his occupying forces would be resented, he was outraged that women would act so abominably toward his men. He later claimed that the controversial order had its desired effect, that "these she-adders of New Orleans were at once tamed into propriety of conduct," but so gross an insult to Southern womanhood was not soon forgotten, nor was the martyrdom of young Billy Mumford, who in death became a Confederate hero.

The depth of Southern loathing for Butler only seemed to increase with time. One Democratic paper late in the war accused him of seeking to disembowel dead soldiers in order to send their corpses north filled with silverwareâ"this representative of Hell in garb of man, this cockeyed insulter of woman, this sensuous incarnation of all that is damnableâthis beast, Benjamin Butler."

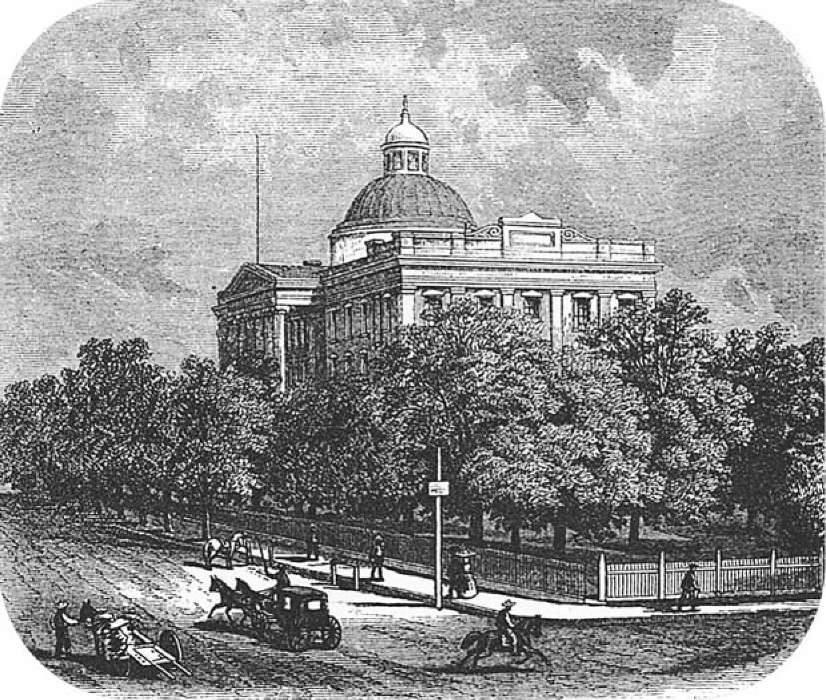

Blanche Butler Ames, although devoted to her husband, didn't fully share his commitment to navigating Mississippi safely through the shoals of Reconstruction; and after the whirlwind of Washington society, a posting in tiny Jackson must have seemed bleak. Despite its handsome state capitol and governor's mansion set on a central hill, the place was still more or less a crossroads town; the state's sparsely populated frontier began almost at the city limits. With greater prescience than

Adelbert, she viewed the surroundings as not merely tedious but immensely hostile, and thus feared for her own, and later her children's, safety. Because of this, she rarely left the "great barn of a house," as she called the mansion. As if to compound her sense of vulnerability, the residence was situated on a prominent site just behind the capitol, not far from where Edward Yerger had killed Colonel Crane, and it was under the almost constant "surveillance" of the walking and carriage-borne public.

STATE CAPITOL, JACKSON, MISSISSIPPI

Blanche recognized Mississippi's "multitudinous disadvantages ... the malarious atmosphere, with its baleful influence upon mind and body, the red, clayey, turfless soil, filled with watercourses and gullies, the slothful indolence of all its people," which she registered as "insurmountable reasons why I could never regard it with favor." But she made an effort to welcome to the mansion Jackson's gentry and her husband's political acquaintances, occasionally asking them onto the lawn to play croquet, although she thought the local women nosy and "lynx-eyed" and was disheartened to find that the town had no qualified engraver of invitations and that the servants were inadequately trained, by eastern standards. Gatherings that mixed her husband's black and white

political followers were less frequent and called for greater circumspection, as they could potentially inflame local opinion.

Despite the presence in Mississippi of conciliatory former rebels such as James Lusk Alcorn and the capable executive Adelbert Ames, efforts to achieve a governing alliance of whites and blacks in the state eroded steadily through the early 1870s. They foundered on the elemental fact that most whites remained unwilling to recognize blacks as their political equals, a resistance that had evolved from the "masterly inactivity" of the constitutional convention phase of Reconstruction, to the bloodshed of the Meridian riot, and finally to ever more strident calls for home rule. By late 1874, agitated by the national debate over a civil rights bill and encouraged by the Democratic Party's reclamation of the House of Representatives, even midstream papers like the

Jackson Clarion

and the

Hinds County Gazette

joined the call from the small-town Mississippi press for "a white man's government, by white men, for the benefit of white men." The

Forest Register

inserted in its masthead the soon-popular motto "A white man in a white man's place, a black man in a black man's place, each according to the eternal fitness of things"; the paper also urged its readers to "carry the election peaceably if we can, forcibly if we must." The

Westville News

offered the headline "Vote the Negro Down or Knock Him Down" as it editorialized, "Let us have a white man's party to rule a white man's country, and do it like white men."

The usual allegations were made that blacks wielded too much authority in the state, although even with 226 black officials serving Mississippi during all twelve years of Reconstruction in every position from U.S. senator to county tax collector, their influence was never truly dominant. There was one black secretary of state, James D. Lynch, and one black lieutenant governor, Alexander K. Davis; the state's nine positions in Congress saw only three black representativesâHiram Revels and Blanche Bruce in the Senate, and John Roy Lynch (unrelated to James) in the Houseâand never was there more than one black Mississippian in either body of Congress at the same time. Of Mississippi's seventy-two counties, only a dozen ever had black sheriffs, and these men did not all serve at the same time. Similarly, blacks never held anything near a majority in either chamber of the state legislature. And while Mississippi whites inevitably complained of excessive taxation and black and carpetbagger corruption, Governor Ames would point out in congressional hearings held in 1876 that Mississippi taxpayers paid only

an average of seventy cents a person in 1875, as compared with sixteen dollars in New York State and thirty-six dollars per inhabitant of New York City. Republican counties in the state tended to be on better financial footing and freer from "plundering" than Democratic ones, Ames cited, and there were few examples anywhere of wholesale corruption.