Casting Off: Cazalet Chronicles Book 4

Read Casting Off: Cazalet Chronicles Book 4 Online

Authors: Elizabeth Jane Howard

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #British, #Historical, #Classics, #Contemporary, #Genre Fiction, #Family Saga, #Literary, #Women's Fiction, #Domestic Life, #Romance, #Contemporary Fiction, #Family Life, #Sagas, #Literary Fiction

To Sybille Bedford

with love and homage

CONTENTS

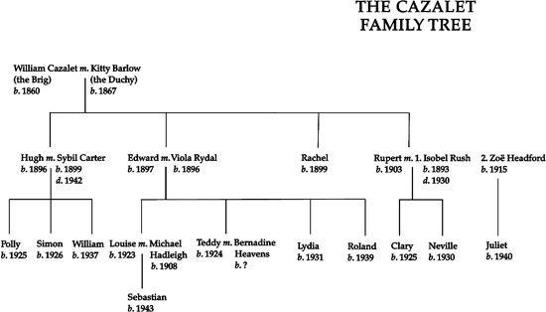

The Cazalet Family and their Servants

The Wives: October–December 1945

The Outsiders: January–April 1946

Polly: September–December 1946

The Wives: December 1946–January 1947

THE CAZALET FAMILIES AND THEIR SERVANTS

W

ILLIAM

C

AZALET

, known as the Brig

Kitty Barlow

, known as the Duchy (his wife)

Rachel, their unmarried daughter

H

UGH

C

AZALET

, eldest son

Sybil Carter

(his late wife)

Polly

Simon

William, known as Wills

E

DWARD

C

AZALET

, second son

Viola

, known as Villy (his wife)

Louise

Teddy

Lydia

Roland, known as Roly

R

UPERT

C

AZALET

, third son

Zoë

(second wife)

Isobel

(first wife; died having Neville)

Clarissa, known as Clary

Neville

Juliet

J

ESSICA

C

ASTLE

(Villy’s sister)

Raymond

(her husband)

Angela

Christopher

Nora

Judy

Mrs Cripps (cook)

Ellen (nurse)

Eileen (maid)

Tonbridge (chauffeur)

McAlpine (gardener)

FOREWORD

The following background is intended for those readers who are unfamiliar with the Cazalet Chronicles, a series of novels whose first three volumes are

The Light Years

,

Marking Time

and

Confusion

.

In the summer of 1945 William and Kitty Cazalet, known to their family as the Brig and the Duchy, are living quietly in the family house, Home Place, in Sussex. The Brig is now blind. They have an unmarried daughter, Rachel, and three sons, who all work in the family timber firm. Hugh is a widower, Edward is married but entangled in a serious affair, and Rupert has just returned to England and his wife Zoë, having been missing in France since Dunkirk.

Edward’s daughter Louise is struggling with her marriage to the portrait painter Michael Hadleigh. They have one son, Sebastian. Louise’s brother Teddy, training in the RAF in Arizona, has not yet returned with his American bride.

Polly and Clary, Hugh’s and Rupert’s daughters, are sharing a flat in London. Polly works for an interior decorator and Clary for a literary agent. Polly’s brother Simon is at Oxford, and Clary’s brother Neville is still at Stowe.

While Rupert was away, Zoë gave birth to their daughter, Juliet.

Rachel lives for others, which her great friend, Margot Sidney (Sid), who is a violin teacher in London, often finds hard.

Edward’s wife, Villy, has a sister, Jessica Castle, married to Raymond. They have four children: Angela, who has become engaged to an American, Christopher, who lives in a caravan with his dog and works for a farmer, Nora, who married a paraplegic and has taken over the Castle house in Surrey as a nursing home for seriously wounded men, and Judy, who is still at boarding school.

Miss Milliment is the very old family governess, and is to live with Villy and Edward when they move back to London.

Diana Mackintosh, Edward’s lady, has had a child by him.

Archie Lestrange, Rupert’s oldest friend, is still working at the Admiralty, and is the recipient of most of the family’s confidences.

Casting Off

begins in July 1945, soon after Rupert’s return to England.

PART ONE

THE BROTHERS

July 1945

‘So I thought if I stayed until the autumn, it would give you plenty of time to find someone suitable. Naturally I wouldn’t want to put you out.’ In the silence that followed, she sought and discovered a small white lace handkerchief in the sleeve of her cardigan and unobtrusively, ineffectively, blew her nose. Her hay fever was always troublesome at this time of year.

Hugh gazed at her in dismay. ‘I shall never find anyone remotely as suitable as you.’ The compliment struck her as a small stone, and she flinched: one of the things she had been dreading about this conversation was his being nice to her.

‘They say nobody is indispensable, don’t they?’ she returned, although when it came to the point, like now, she did not feel this to be true at all.

‘You’ve been with me so long I shall be lost without you.’ When she had first come, all the girls had had shingled hair; hers was now grey. ‘It must be over twenty years. Goodness, how time flies.’

‘That’s what they say.’ This, she thought, was not true either. But in all of the twenty-three years she would never have dreamed of arguing with him. She could see now that he was upset: a small pulse at the side of his forehead became noticeable, and any moment now he would run his hand fretfully on to it and up into his hair.

‘And I suppose,’ he said, when he had finished rubbing his head, ‘that there is no way that I could get you to change your mind?’

She shook her head. ‘It’s Mother, you see. As I said earlier, she can’t manage on her own all day any more.’

There was a short silence as he recognised that they were back at the beginning of the conversation. She moved his laurel-wood cigarette box towards him – she had filled it that morning as usual; it was so much easier for him with one hand than struggling to open packets – and waited while he took one and lit it with the silver lighter that Mrs Hugh had given him the year of the Coronation. That had been the year that the firm had supplied the elm for all of the stools for the Abbey; she had seen the one that Mr Edward had bought afterwards – lovely it had looked with its blue velvet and gold braid. She’d felt proud that it was

their

wood that had been chosen for a piece of history. Her retirement would be full of memories.

‘I was wondering,’ she said, ‘whether you would care for me to assist you in finding a new person?’

‘Do you know somebody who might do?’

‘Oh, no! I just thought that perhaps I could have helped to sort out the people who applied for an interview.’

‘I’m sure you’d do that far better than I should.’ His head was beginning to throb.

‘Would you like me to open the window?’

‘Do. No good being hermetically sealed on a day like this.’

As soon as she had undone the window bolt and heaved up the heavy sash a few inches the warm breeze carried in with it the staccato, raucous cries of the old news-vendor from the street corner below. ‘Election special! Two Cabinet ministers out! Big swing to Labour! Read all about it!’

‘Send Tommy out for a paper, would you, Miss Pearson? It sounds like bad news, but we’d better know the worst.’

She went herself, as Tommy, the office boy, combined being chronically elusive with a capacity for slow motion that would, as Mr Rupert had once remarked in her hearing, do credit to a two-toed sloth. She would miss them

all

, she told herself, trying to spread the awful sense of impending loss. And this was just the beginning of it. There would be a farewell party in the office, everybody wishing her luck and drinking her health, and they might – probably

would

– have a whip-round for a leaving present. Then she would wait for the bus that took her to the station for the last time, walk the twenty minutes from New Cross to Laburnum Grove until she reached number eighty-four, insert the key in the door – then shut herself in and that would be that. Mother had always resented her because she had been born out of wedlock – was no better than she should be, as Mother would say whenever she got really fed up. She

would

get out, of course, to go to the shops and to change their library books and perhaps, occasionally, she might slip out to the cinema, although she was going to have to be very careful with money. By retiring so much earlier than she had meant to she would be forfeiting quite a proportion of her pension that the firm arranged for all its employees. Holidays, in any case, would be out of the question unless Mother’s incontinence cleared up – which she supposed it might do if she was at home all day to prevent it.

It had crossed her mind these last weeks that Mother was doing it on purpose, but it wasn’t very kind to think like that.

When she got back to Mr Hugh with the paper it was clear that he’d got one of his heads. He’d pulled down the top blind on the window so that the sun no longer fell across the desk, winking on the large silver inkstand that he never used. She laid the paper on the desk.

‘Good Lord!’ he said. ‘Macmillan and Bracken out. Landslide predicted. Poor old Churchill!’

‘It does seem a shame, doesn’t it? After all he’s done for us.’ She left him then, but before settling in the little back room where she typed and kept her files, she did feel it right to say that of course she would stay – until September anyway, and longer if he had difficulty in finding the right substitute.