Climbing Up to Glory (20 page)

Read Climbing Up to Glory Online

Authors: Wilbert L. Jenkins

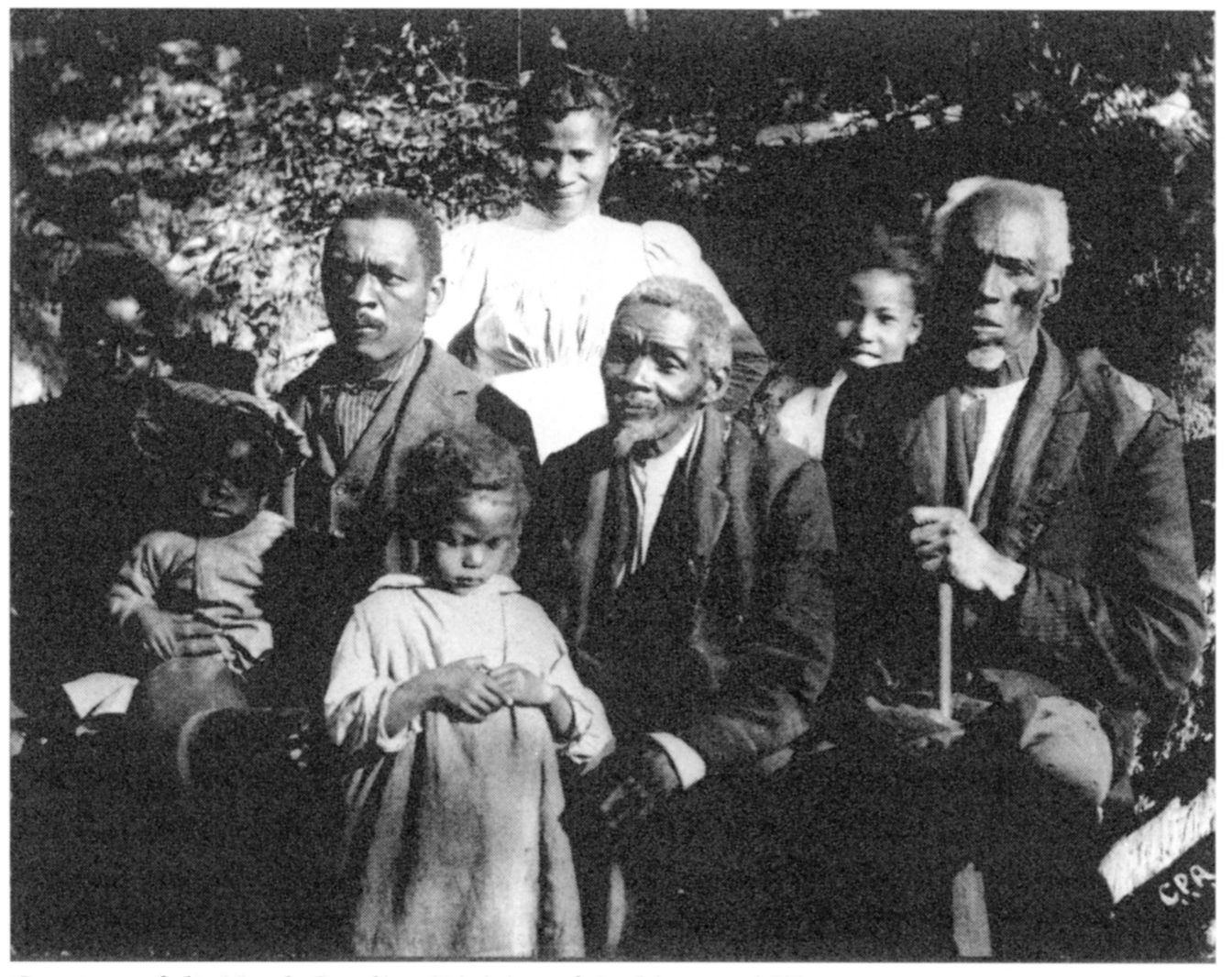

AN UNIDENTIFIED BLACK FAMILY DURING RECONSTRUCTION.

Courtesy of the North Carolina Division of Archives and History

Some blacks chose never to marry. Lizzie Atkins, for example, did not marry because her lover was killed during the Civil War. “Iâse never did see another man that I ever wanted so I just stayed at home and took care of my old mother and father.” Nevertheless, she thought that she would have been better off if she had married “because times sure have been hard on the poor old negro since he was freed.”

58

For James Brooks, “women [were] too much trouble. Want too much âttention. I couldn't be bothered wid 'em.”

59

Lizzie Polk never exchanged marital vows because “I was working too hard to have time to flirt. Anyway, if I had to work, I would rather work for myself than for a may.”

60

Blacks regarded the twin institutions of marriage and family as sacred. Thus, by 1870, a large majority lived in two-parent households,

61

There were several reasons why blacks found marriage appealing. Undoubtedly, many married for love, as was the case for Maggie Jackson: “I didn't marry John âcause I wanted to leave home. I married him 'cause I loved him and he loved me.”

62

Blacks also considered marriage to be morally right. Moreover, it established the legitimacy of children and helped blacks gain access to land titles and other economic opportunities. Black soldiers in particular wanted to formalize marriages because they feared that their women and children would have no legal claims in the event that they were killed.

63

Furthermore, church membership often required legalized marriage. Susan Grant explained that she and Aaron Grant as well as several other couples were living together when their preachers “told them that the[y] must get married and that they, as did many others, got up in church and were married.” A friend of Susan and Aaron Grant, Judith Swinton, explained that after the war churches “compelled the members who were living together as man and wife but not married to have these ceremonies performed.”

64

In fact, the First African Baptist Church of New Orleans, after the abolition of slavery, declared: “Any persons wishing to become members of this church who may be living in a state of illegitimate marriage should first procure a license and marry.”

65

Since marriage conformed to the laws of civil society, the enforcement of legal marriage was therefore a matter of concern for the entire community. A Freedmen's Bureau agent, J. E. Eldredge, reported from Bladenboro, North Carolina, that “the Colored people of this place are trying to make their colored brethren pay some respect to themselves and the laws of the country by making them pay some respect to the marriage bond.” Blacks in Bladenboro targeted one case in particular. A black man had promised on four different occasions to marry a woman whom he had lived with for a year. However, he continually put her off. As a result, the Bureau agent noted, “the colored men of this place appointed a committee to wait on him and see if they could not influence him to do better but no satisfaction could be obtained.”

66

In another case, a group of blacks at a contraband camp enthusiastically supported the expulsion of a black minister who refused to marry his mistress from the camp. Shortly thereafter, the couple died of smallpox. Upon their deaths, there was no mourning among blacks at the camp, for their demise, observed the officer in charge, “was looked upon by the Negroes as a direct and swift application of retributive justice.”

67

To the newly freed blacks, the work of emancipation would be incomplete until the families dispersed by slavery were reunited. Some freedmen set out on their own to find lost relatives. One journalist from the North reported encountering a black man in September 1865 who had walked more than six hundred miles from Georgia to North Carolina in the hope of finding his wife and children from whom he had been separated by sale.

68

Sarah Jane Foster, a Northern white teacher of freedmen in the vicinity of Charleston, wrote: “One woman here has exerted herself to find her four children at great expense, though dependent on her own labor altogether.”

69

Many advertised in black newspapers in efforts to locate lost loved ones. A typical plea for help appeared in the Nashville

Colored Tennessean:

“During the year 1849, Thomas Sumple carried away from this city, as his slaves, our daughter, Polly and son.... We will give $100 each for them to any person who will assist them... to get to Nashville, or get word to us of their whereabouts.”

70

Sometimes blacks solicited the aid of whites or other blacks in the hope of tracking down family members. Unfortunately, when giving descriptions, some failed to take into account the fact that many of the lost children were now adults. Such was the case when Elizabeth Botume reported that she came across an old slave woman in Central Georgia who had been sold away from Virginia some thirty or forty years earlier. The woman left a daughter in Virginia whom she had not heard from since their forced separation. Upon learning that Botume had traveled through the region, the old woman wanted to know if she had seen her “little gal.” “With tears streaming down her face, she told me what a âstore she set by that little child',” noted Botume. “She begged me to look out for her when I went back. She was sure I should know her, she âwas such a pretty little gal.' ” Botume concluded that “it was useless to tell her the girl was now a woman, and doubtless had children of her own.”

71

Unfortunately, a large number of freed blacks were unable to find lost loved ones, although there were some successes. A former slave recounted the stories of dozens of children who searched throughout the South after the Civil War for parents sold “down the river” and of parents who searched equally desperately for their children. Lizzie Baker's family tried to get some news of her brother's and sister's whereabouts after the war, as her mother “kept âquiring 'bout âem as long as she lived and I have hoped dat I could hear from 'em. Dey are dead long ago I recons, and I guess dare aint no use ever expectinâ to see 'em.”

72

Another former slave, Mattie Curtis, recalled that after the war her parents “tried to find dere fourteen oldest chilluns what was sold away, but dey never did find but three of dem.”

73

Fortunately, others had better luck. Laura Redmoun advertised “roun' in the papers and found my mammy and she came and lived with me.”

74

After exhaustive efforts, Kate Drumgold found her children alive.

75

After the war, Charles Maho, a former slave who had been sold away from his wife and daughter in Virginia in the late 1850s to a Mississippi cotton planter, set out for Richmond to find them. When he finally reached the city, he was disheartened to learn that his wife had been dead for years. But he did locate his daughter, and the two shared an apartment while he worked in a tobacco factory to support them. Olmstead Scott, from Virginia, was another former slave who was sold in 1860 to a planter in Florida. After the war, Scott saved money so he could return to Richmond and try to reunite with family members. He arrived there in 1869 and found his grandmother, his aunt and uncle, and his brother and sister, but he discovered that his parents had died before the war.

76

Another freedman who traveled throughout the South for twenty years looking for his wife finally found her in a refugee camp.

77

One former slave recalled the joyous moment when his mother located him after the war. He couldn't believe it was she. “Then she took the bundle off her hand [

sic

] and took off her hat, and I saw that scar on her face. Child, look like I had wings!”

78

Equally exciting was the reunion of Chaplain Garland H. White of the Twenty-eighth U.S. Colored Infantry with his mother. White had initially been a slave in Richmond but was sold to Robert Toombs, a lawyer in Georgia, when he was a small boy. After the war began, White's mother came across Toombs in Richmond with troops from his state. When she asked him where his body servant Garland was, Toombs informed her that Garland had escaped to Canada and was probably living somewhere in Ohio. The mother continued to inquire about one Garland White of Ohio until some of the soldiers in her son's regiment overheard her. Shortly thereafter, the soldiers found White and told him, “Chaplain, here is a lady that wishes to see you.” He turned and followed them until he came upon a group of black women. Of the occasion, White wrote, “I cannot express the joy I felt at this happy meeting of my mother and other friends.”

79

Another freedman who ended up in Illinois after the war surprised his family by returning home to Roxboro, North Carolina. His overjoyed parents had not seen him in several years. The father “had a few days previously remarked that he did not want to die without seeing his son once more.” The son recalled that he “could not find language to express my feelings. I did not know before I came home whether my parents were dead or alive.”

80

In another story, one soldier recalled that some men “cried while others laughed to hide the tears” when they witnessed a black woman reunite with her lost daughter, who had been sold away ten years earlier.

81

On some occasions the Freedmen's Bureau helped former slaves obtain information about missing relatives. In May 1867, Hawkins Wilson, in Texas wrote to the Bureau seeking assistance in finding his sisters, whom he had not seen in twenty-four years. He sought the aid of the Bureau because “I have no other one to apply to but you and am persuaded that you will help one who stands in need of your services as I doâI shall be very grateful to you, if you oblige me in this matter.” He informed the Bureau that one of his sisters, Jane, belonged to Peter Coleman in Caroline County. Wilson also provided the name of his sister's husband, her owner, and his area of residency as well as the names of his sister's three children at the time he left. Next, he did the same for his other two sisters, Martha and Matilda. Finally, Wilson alerted the Bureau about his Uncle Jim and Aunt Adie and their oldest son Buck, who all belonged to Jack Langley. With much emotion and anticipation, Wilson asserted, “These are all my own dearest relatives and I wish to correspond with them with a view to visit them as soon as I can hear from them.”

82

In addition, Milly Johnson, a freedwoman in North Carolina, solicited the assistance of the Freedmen's Bureau to locate her five children.

83

And John Allen of Austin, Texas, enlisted the aid of the Bureau in finding his two children, whom he left in Batesville, Arkansas, in 1859. Allen's daughter Rachel was just nine years old at the time, and Benjamin, his son, was two years younger. Despite the fact that Allen had not heard from them since their separation, he was “anxious” to know if they were still alive and wanted them again “under his charge and protection.”

84

As were the cases when black parents searched for family members on their own, placed advertisements in black newspapers, and solicited the aid of individuals, results were often either disappointing or mixed. Hawkins Wilson's kinfolk probably were never found. Likewise, John Allen probably never reunited with his two children. However, Milly Johnson located her daughter Anna, found information about two of her children but received no word about the others.

If freed blacks knew exactly where their family members had relocated, Freedmen's Bureau agents routinely arranged transportation to facilitate reunions. Willis Love, for instance, a black bricklayer “of good character,” successfully petitioned the Bureau for assistance. Agents were assured by Love that he would support his children, but he could not afford the fare for their passage to Atlanta to join him.

85

Marcia Johnson was also able to solicit help from the Bureau to rejoin her husband. She had “walked, worked, and scuffed along from West Point, Mississippi” in efforts to reach Tarboro, North Carolina, where her husband resided. She was now in Raleigh, some forty miles away, “but now that all her means and strength are exhausted she can go no further.”

86

Some former slaves experienced complications with the law in attempting reunions, but others experienced complications of the heart when they found themselves having to choose one spouse over another. As slaves, they had started second families after being forced into separations assumed to be permanent, whether because of the sale of one mate or because of an escape. Robert Washington, for example, had escaped to the North from South Carolina before the war. When he returned to Charleston in 1870 to claim his wife, Lucretia, and their children, he found that Lucretia had taken another husband. He went to court to win her back, but the magistrate who heard the case, T. J. Mackey, ruled against him. In Mackey's opinion, Washington should have had enough interest in Lucretia to have returned to Charleston long before he did.

87

A more complicated story involved a Virginian, Philip Grey, and his wife, Willie Ann. Philip and Willie Ann had married before the war and had one child, Maria. Willie Ann and Maria were then taken to Kentucky. Philip never remarried, but Willie Ann married a Federal soldier who was killed in battle; three children were born to this union. After the war, Philip searched for his wife and daughter. It was obvious that Philip wanted his daughter back, but he was less sure about Willie Ann, although she still loved him and wanted to return to him. In an impassioned letter to Philip, Willie Ann wrote, “I know that I have lived with you and loved you then and I love you still... every time I hear from you my love grows stronger.” Nonetheless, Willie Ann insisted that Philip accept her now-fatherless other three children: “You must not think my family to large and get out of heart for if you love me you will love my children and you will have to promise me that you will provide for them all as well as if they were your own.”

88

It is not clear whether Philip and Willie Ann Grey ever lived again together as husband and wife.

Cases involving two spouses and two sets of children were especially troubling and difficult to settle. James McCullum of North Carolina married again four years after his wife and two children were sold. Two children were also born to him and his second wife. When the war ended, McCullum's first wife and children returned to him, and he now had two wives and two sets of children to choose from. Although he believed that only his first marriage was valid, McCullum sought a ruling from the Freedmen's Bureau in Lumberton, North Carolina.

89

Similarly, Elizabeth Botume reported the case of a woman whose husband was first sold away and then went into the army. Since she was again single, the woman took a second husband. Once the war concluded, the regiment of husband number one disbanded, and he returned to claim his wife. The woman had given birth to two boys with him, and a girl with husband number two. Both men wanted their own children. The poor woman was in a quandary.

90

Even more heart-wrenching was the experience of Laura Spicer and her slave husband, who had been separated for many years. The husband, assuming that Laura was dead, remarried and established a new family. After the war, he was shocked to learn that Laura was still alive. Although he decided to stay with his second wife, Anna, and refuse Laura, he reached that decision with great difficulty. In a series of letters to Laura, he wrote out his feelings:

I would come and see you but I know you could not bear it.... You know it never was our wishes to be separated from each other, and it never was our fault.... I had rather anything had happened to me most than ever have been parted from you and the children. As I am, I do not know which I love best, you or Anna.... I do not think I would die satisfied till you tell me you will try and marry some good, smart man that will take good care of you and the children; and do it because you love me; and not because I think more of the wife I have got than I do of you. The woman is not born that feels as near to me as you do.

91

Sometimes freedmen and women found their relatives without at first knowing it. Since as slaves blacks were often separated from family at an early age, mothers sometimes did not recognize their children as adults and brothers and sisters did not recognize each other. As a result, they might marry each other without being aware of their kinship. William Mathews recalled, “After de war when dey was all free, dey marry who dey want to an' sometime a long time after dat dey find out dat brothers had married dere siters an' mothers had married dere sons, an' things like dat.”

92

Richard Carruthers maintained that he knew of many cases where brothers and sisters married. He offered the following scenario of how they usually found out that they were siblings: “One night they gits to talking. She say, âOne time my brother had fight and he git a awful scar over his left ear. It long and slick and no hair grows there.' He say, âSee this scar over my let ear? It long and slick and no sign of a hair.' Then she say, âLawd God help us po' niggers. You is my brother.' ”

93