Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. (22 page)

Read Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. Online

Authors: Viv Albertine

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

Don tries to control us but it’s impossible. It’s all so new, to all of us, no one knows what to do or how to do it. Ari shouldn’t even be on the tour, not just because of school, she’s too young to even be in the venues; if the promoters get a whiff of it and want to get rid of us, we’ll be sent home. Don tries to be sensible, tells Ari to be in bed at a certain time and not to come out of her room, but with all the boys enjoying themselves in the bar and us excluded like little children, it’s hopeless. We feel like outsiders so that’s how we behave. We race up and down the corridors, banging on doors, pissing in shoes left in the corridor, playing music too loud, shouting, swearing and spitting. We’re definitely the most controversial band on the tour and although the Clash support us musically, they also want to have a successful tour; they’re not going to jeopardise that, so I’m quite stressed a lot of the time. Ari isn’t bothered, she doesn’t know that opportunities like this don’t come along very often.

I become so nervous that before every show I get a kind of narcolepsy; I can’t move my legs or arms, my eyes won’t stay open and my brain goes foggy. We leave the dressing room and I drift like a sleepwalker towards the stage. I say to the others in a panicky voice, ‘I can’t go on, I can’t walk, I can’t keep awake.’ They ignore me, thank goodness, and the second I step out onto the stage, it’s gone, I’m full of energy.

Something that doesn’t help my nervousness is that Tessa gets pissed before the shows. If the bass player falls apart, it doesn’t matter how good the rest of us are, the show is going to be a mess. Palmolive used to drink before shows too, but after a band meeting where me and Ari put the case for them both to wait until afterwards, she’s stopped.

Our shows are still great, even though they’re not as together as they could be. Most of the audience have never seen girls play music before, let alone with the fuck-off attitude we’ve got. Lots of people come just to have a look at us and cause trouble. They think ‘punk’ is an excuse to let their frustrations out in a violent, non-creative way. The hysterical media coverage of the Pistols’ swearing on Bill Grundy’s

Today

show has added to that.

The Slits are a very tight gang and we believe a hundred per cent in what we’re doing. For all our arguments – sometimes there are even scuffles between the other three on stage – we’re extremely protective of each other. As soon as we leave the stage the roadies start to dismantle Palmolive’s sparkly purple drum kit – bought for her by Nora – and we rush into our dressing room to eat the rider. There are carrot sticks and chocolate bars, Coke, celery, crisps and sandwiches. It’s like a children’s tea party every night. I’m in heaven. Now all my nerves have gone I can enjoy the rest of the evening.

There’s an argument backstage when I say to Palmolive she should wear a bra when she plays, her boobs bounce about because she drums so manically. She says that she’s a free person and this is who she is, why should she change? That it’s more feminist to not wear a bra than wear one. I argue back that although she’s right, the impression she gives off whilst playing doesn’t match her ideals. ‘We won’t be taken seriously if people are looking at your tits. Even I’m looking at your tits when you play. It’s not the reason we want people to look at us.’ I know she’s wild and untamed, it’s not a sexual thing, but most people have never seen a girl drum before and instead of watching her play and thinking she’s great, they’re fascinated by her boobs bouncing up and down. Eventually we reach a compromise and Palmolive agrees to wear a tight body-stocking which sort of straps them down.

Subway Sect are so different to the Slits, very understated, they look like they’ve been kitted out by one of those old-fashioned boys’ and men’s outfitters. Hand-knitted, V-neck grey jumpers, black school trousers and brown suede Hush Puppies – they make everyone else look gaudy and overdressed. They’re anti-rock in every way. No wide-legged stance and low-slung guitars. No dancing, leaping about, posturing or snarling aggression. The lead singer, Vic Godard, leans nonchalantly on the mike stand; he makes no attempt to be entertaining. His nasal voice, cynical lyrics and dry delivery make him seem slightly superior.

I feel drawn to the guitarist, Rob, who I think is beautiful and mysterious. I watch him during soundchecks, sitting with his knees pressed together, feet turned in; he’s so delicate and shy. He has a gentle, unassuming air about him. I smile and say a few words whenever I can and he slowly starts to open up and talk to me. I learn little things about him: how he is not at all streetwise, he went to an all-boys school, he doesn’t know many girls, has never slept with a girl, has strong views and opinions on music and film, reads a lot. I think he plays guitar really well but he tells me he only knows two chord shapes. He’s not ashamed of being himself. Not trying to be anything he’s not.

Rob and I get closer as the tour progresses. It’s not too difficult to hide this from Mick; often the support bands stay in cheaper hotels than the Clash – they’re not being mean, they’re subsidising all of us. Mick says I can stay with him but I say no, I have to be with my band. I don’t tell him I also want to hang out with Subway Sect and the Buzzcocks.

Rob and I often spend the night snuggled up together in a single bed in one of Subway Sect’s rooms. We don’t have sex, we lie facing each other holding hands and I make him promise he will not be the first one to close his eyes and go to sleep. He has the most beautiful green eyes and he looks through his long lashes at me until I fall asleep. He understands. He’s intense and serious and romantic, like me. We start spending more and more time together. After we’ve finished our sets, we meet in the wings of whichever bingo hall, ballroom or Top Rank night club we’re playing that night. When the Clash have taken to the stage, we run down the corridor – ‘London’s Burning’ fading into the distance until it’s just a dull thump of bass and drums – push open the fire doors and escape out into the night.

Cold air hits me in the face and jolts me out of my romantic little fantasy. Why do I feel like I’m escaping from authority, from my parents or my teachers? It’s Mick and the Clash for god’s sake. My boyfriend, my friends. I feel guilty; even though there’s nothing physical between me and Rob, I know I’m not being fair to Mick, he thinks I’m in the audience watching him. What I’m doing is a betrayal. Not just to him personally, but to the Clash, who invited us on the tour and are paying for us to be here. No wonder Bernie Rhodes hates me.

I shiver. I’m wearing a pale pink short-sleeved T-shirt from Sex, printed with text from a cheesy porn novel and zips over the breasts, black leather jeans and Converse baseball boots. Rob takes off his black Harrington jacket and wraps it round my shoulders. We head off to explore Newcastle. It’s like a ghost town, boarded up, closed down – even poorer than London. Litter blows around and catches on lamp posts, weeds grow out of the pavement. We pass the corner shop, the bingo hall and the Co-op. The street lights flick on and off, most of them aren’t working. Factory chimneys poke out of the mist on the edge of town. It’s a dirty old town, just like Ewan MacColl’s song about Salford.

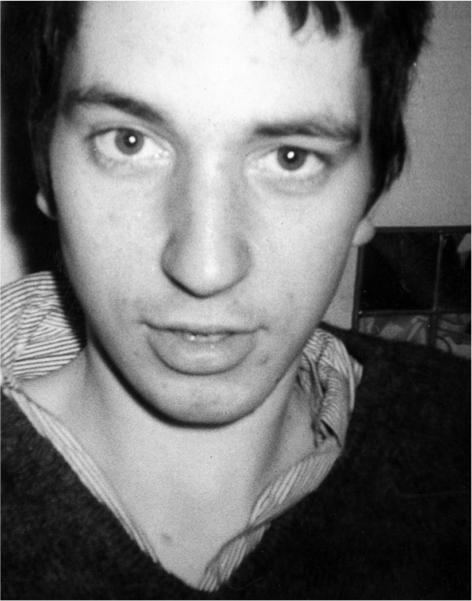

Rob Symmons from Subway Sect, 1977

‘I feel like we’re in one of those sixties films,

Saturday Night and Sunday Morning

or

A Kind of Loving,’

says Rob.

Yeah, the city is as black and white as those old films, and grey, grey, grey. It’s like nothing has changed here for years, and they don’t think it’s ever going to change either. They think this is how England is always going to be. Well, not if us lot have anything to do with it.

We walk to the docks and climb over the boats until we find one with the cabin unlocked. We sit huddled together as it rocks on the water, talking until morning, carried away by our mission.

We’re pioneers. We’re fearless. Above the law

. When it’s light we try and find our way back to the hotel. We’re hungry and broke, but even though we could easily nick a bottle of milk off a doorstep, there’s no way we’re going to drink milk. We find a greasy spoon and order a cup of tea and a KitKat between us. Then we head back to the hotel, arriving before anyone is awake. I go to my room and stuff my clothes into my bright pink plastic suitcase. Ari looks up from her pillow sleepily. I’m exhausted, but I can sleep on the coach.

The following night we’re all staying in a fancy hotel as a treat, paid for by the Clash. It’s so fancy that the Manchester hotel manager hasn’t thought to call ahead and warn them we’re coming. As soon as we arrive, I dump my suitcase and go to Subway Sect’s room. We’re all sitting on the beds talking when we hear muffled shouting outside. Mick is stomping down the corridor, he sounds furious. We all know what it’s about.

‘Where are you?’ he bellows. He hammers on the doors, booting them open one by one – getting louder as he gets nearer.

Paul Myers, Subway’s bass player, is quaking in his Hush Puppies. ‘Sit apart, you two, sit apart!’ he says to me and Rob.

‘Don’t you worry about that Jones,’ says Vic. ‘He’s just a little squirt, we can duff him up.’

Mick reaches our door and kicks it open. He’s worked himself up into a right state. Glowering next to him is his mate from school, Robin Banks (Mick wrote ‘Stay Free’ about him). Unlike Mick, Robin is actually quite scary, he’s done time in the nick. Although what they see is a pretty innocent scene – me, Rob and Paul on one bed, Vic and Mark Laff on the other – Mick is angry and upset. I know I’m wrong and he’s right, what he suspects is happening

is

happening, but I pretend he’s imagining it all. I tell him to calm down, we’re just sitting around chatting. He threatens to get Rob thrown off the tour.

I jump off the bed and go out into the corridor to take the heat off the boys. There’s a scuffle between me and Mick. The Slits appear out of their rooms and try to intervene. Robin weighs in. He thumps Palmolive and beats up Rob. Now it really kicks off – a ball of arms, legs and fisticuffs goes rolling down the corridor, like a scene from the Bash Street Kids.

Mick and I break up.

No more smart hotels for us, from now on we’re in B & Bs, cracked washbasins in the corners of the rooms, bathrooms down the hall and beds with smelly nylon sheets. I lay my clothes down over the bedclothes and cover the pillow with a T-shirt before I go to sleep, so I don’t have to lie on them.

Next gig is the Rainbow in London. I’ve been going to the Rainbow to see bands like Alice Cooper, Arthur Brown, Rod Stewart and the Faces for years. I’d see anything and everything there, I knew people who worked behind the bar and they’d get me in. Never did I dream that one day I would be on this stage. Even the Beatles and Jimi Hendrix have played here. My mum comes to the show and I’m so happy that the Slits are good tonight.

On the last night of the tour, we play the California Ballroom in Dunstable. All the support bands have made a plan that at the end of Subway Sect’s set we’re going to go on stage and play the Velvet Underground song ‘Sister Ray’. We all steam on, the Slits, Buzzcocks, the Prefects and Subway Sect – singing and playing for ages, we make a terrible racket. Mick’s annoyed that he didn’t get asked to play.

The Clash come on after us and the crowd goes wild, but something’s not right.

During the dub bit of ‘Police and Thieves’, Mick calls into the mike in a heartbroken voice. ‘Where are you? Where are you?’ It’s so sad, it’s terrible to hear. I start to cry. I go out front and listen to the Clash’s last set, then go back to my hotel room alone. I don’t feel like partying.

In the morning the Slits have to leave before the Clash. We’re all going our separate ways. Mick’s given instructions that he’s not to be disturbed but my guitar is in his room. He has all the guitars in his room overnight for safe keeping, wherever we play.

I find a roadie, and tell him, ‘I’ve got to get my guitar out of Mick’s room, we’re leaving.’ The roadie says there’s no way he can let me into the room, he has strict instructions. I smile sweetly. ‘I’ll just tiptoe in and out, he won’t even know I’ve been there. Anyway, Mick won’t mind, we’re still good friends.’ The roadie unlocks the door.

The room is stuffy and airless and swamped in yellow light from the thick gold curtains. It smells like a stagnant pond. I look over at the bed. I can just make out Mick, and beside him, a girl, fast asleep. I’m jealous. Pain stabs at my heart. But the pain is quickly replaced by fury. I leap onto the end of the bed and jump up and down. They’re shaken awake – I keep jumping like a maniac, making the bed bounce violently, Mick and the girl are tossed about like boats on a stormy sea, their heads thumping against the pillows. The roadie runs out of the room. Mick leans over to the bedside table, picks up a water jug and hurls it at me. I duck and it smashes into a mirror. Water and glass shards spray all over the guitar cases.

‘Pathetic,’ I say as I jump off the bed, pick up my guitar and scoot out of the room.

That’s the end of the

White Riot

tour.

A week later I get a call from Mick at my mum’s.

Me: ‘Hello?’