Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. (21 page)

Read Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. Online

Authors: Viv Albertine

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

She’s dressed like this, in a tiny skirt, sparkly tights and an oversized lurex drape jacket, when, in an attempt to bond, I agree to go along to a reggae night at the 100 Club with her. When Ari listens to reggae on a cassette player, she rocks backwards and forwards manically, sometimes for five or six hours on end. It calms her down, especially on long journeys to gigs. She’s obsessive about the bass lines, the drum patterns, the lyrics (I could almost hate reggae for the way she’s taken it and made it her own, as if she invented it).

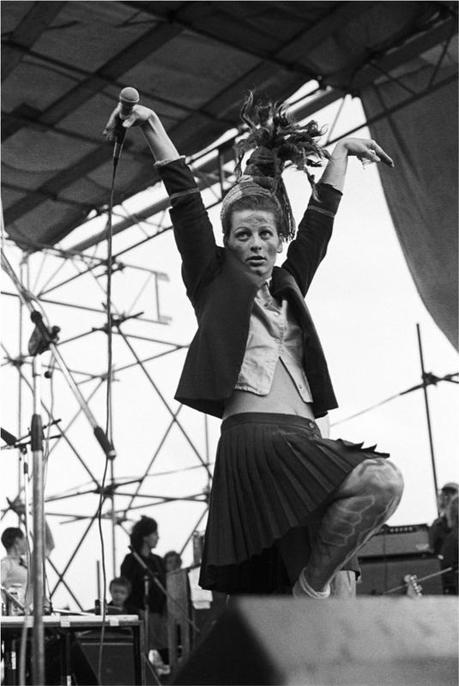

At the 100 Club, Ari takes over the dancefloor, displaying her extraordinary dance style, which is cobbled together and customised from watching young boys at sound systems we go to, like Sir Coxsone and Jah Shaka, or late-night clubs in Dalston, Phoebe’s and the Four Aces. We’re often the only girls at these all-nighters, and the fact that we are white and dressed so strangely is even more extraordinary, but no one gives us any trouble or is antagonistic towards us. Ari never watches the girls dance, they’re too discreet and understated, just shifting from one foot to the other – she watches the athletic boys and copies what they do. She’s amalgamated their moves and now has an amazing praying mantis dance style, reminiscent of White Crane kung fu. She bobs up and down on one bent leg, using her arms and hands as claws, or feelers – it’s very beautiful, sometimes funny, almost mime, telling little stories to the music. People clear a space round her and she gets lost in the rhythm.

Ari dancing, 1980

When the 100 Club closes, we all spill out onto the pavement, but Ari doesn’t want to go home, she’s still buzzing from dancing all evening. She starts chatting to two older guys and asks them if there’s anything else going on. At first they say no but then they remember there’s a party in Peckham. They tell us to wait whilst they go and get their car. I really don’t want to go to a party but I don’t want to seem a bore so I go along with it.

The guys pull up and we climb in the back. By the time we’re on the Mall, heading towards Buckingham Palace, I’m dreading the thought of spending a couple of hours, maybe all night, at a house party in Peckham and, knowing I’m being a drag, I confess to Ari that I don’t want to go. She tries to persuade me but I’ve made up my mind. I tell her she shouldn’t go either; it’s too far away and she doesn’t know these guys – I say she’ll just have to let it go and come home with me. But she refuses, she loves the idea of meeting new people and she loves dancing, she can happily dance all night.

I give up trying to persuade Ari and ask the guys to stop the car and let me out. As I say it, I get a tiny little twinge in my chest and realise I’m worried they won’t stop. They haven’t given me any reason to be suspicious, but I’m relieved when the driver slows down and pulls over. I scoot out quickly and lean into the back seat to have one more try at persuading Ari to come with me. She’s adamant she’s going to the party, they drive off. I’m so relieved that I’m out of the car and not going to Peckham. I walk back up to Trafalgar Square and get the night bus home.

About six months later, when Ari and I are alone, she tells me what happened after I left her that night. They drove to Peckham and pulled up in front of a big old house. Ari and one of the guys went inside, the other guy went to park the car. When they got inside Ari saw that the house was empty, abandoned, derelict. The guy grabbed her and raped her. He was so violent she begged him not to cut her face. After a few hours he left, saying if she told anyone about it, he’d find her and kill her. This was her first sexual experience. She said she was embarrassed to tell me at the time because she’d been such a fool, said she should have listened to me. It broke my heart in so many ways. She didn’t let this experience define her though. After a while she healed and went on to enjoy a normal, healthy sex life and then I knew for sure that she was a stronger person than me. I also realised I was right to trust my instincts. No matter how silly you feel or uncool you look, no matter how small that voice inside you is, that voice telling you something isn’t right: listen to it.

46 WHITE RIOT

1977

We are not afraid of ruins.

Buenaventura Durruti

Mick and I are back together again and in a week’s time the Slits are going on the

White Riot

tour with the Clash. I’ve got to learn all our songs, I can’t even play guitar standing up yet. We haven’t played a gig together either, so we go down to the Pindar of Wakefield pub in Islington to see if we can have a quick go on their stage. When we arrive we see that a bunch of boys are churning out some old rock music, we’ve got our guitars with us but we hold them behind our backs so no one suspects anything. In between songs I go up to the guitarist in the rock band and ask him if we can play a song. He says no, so I pull him off stage and Ari, Tessa and Palmolive pull the other guys off, there’s an uproar, a couple of cymbals get kicked over but Palmolive doesn’t care, she doesn’t use them anyway. We bash through ‘Let’s Do the Split’ before the manager and barmen pull us off. That’s our warm-up gig done.

I’ve only been playing guitar for five months – and now here I am standing in the wings of the Edinburgh Playhouse, looking out at hundreds of people, waiting to go on stage. Mick comes up behind me: ‘Sorry you didn’t get to soundcheck.’ We arrived too late to soundcheck but I’m not bothered, never done one before, wouldn’t know what to do anyway. I am bothered about my clothes though. I’m wearing silver rubber stockings and black stiletto patent boots from Sex, a short blue ballet tunic that I’ve had since I was eleven, and loads of ribbons tied in my matted bleached blonde hair. Just as we’re about to go on stage, I look down and see that one of my brand-new rubber stockings has a rip in it, all the way from my knee up to my thigh. It flaps like a gutted fish. How did that happen? I took such care putting them on, used loads of talcum powder so they slid on easily. All my other clothes are back at the hotel. A roadie, seeing my distress, leaps to the rescue and tapes up the slash with a long strip of black gaffer tape. Looks quite cool.

I count in the first song, ‘One two three four!’ and off we go, careening through ‘Let’s Do the Split’ and ‘I’ll Shit on It’ as fast as we can. (Mick explains to me later in the tour that when you shout ‘One two three four’ you’re setting the speed of the song. I don’t know this, I’ve copied it off the

Ramones

LP, I just think it’s a warning to the band that you’re starting and it’s to be shouted as fast as possible, the quicker, the more exciting.) We all play at different speeds. Ari screams as loud as she can, I thrash at my guitar, Palmolive smashes the drums – the stage is so big and Tessa’s so far away, I can’t hear what she’s doing. I can’t differentiate between the instruments. There’s roaring and squealing and air rushing and heat, like we’ve all been hurled into the mouth of a volcano. We all play the song separately, we know we should play together, but we can’t. I hope that if I remember my part and the others remember theirs, with a bit of luck we’ll all end at the same time. That doesn’t happen. During rehearsals, at least one of us usually makes a mistake and plays the chorus twice, or forgets a change into the next section and ends up in a completely different place to the others, but we all keep playing until the end of the song, often a whole verse behind. That’s what happens with ‘Let’s Do the Split’: we all finish at different times. Palmolive is the last, still clattering away obliviously, the rest of us glare at her and eventually she looks up, realises we’ve all finished, gives the side tom a couple more thumps and stops.

‘One two three four!’ On to ‘Shoplifting’. If my guitar’s out of tune, I can’t tell – sometimes Ari tells me it is, but what can I do about it? No way I can tune it myself. I keep playing. We’re only on for fifteen minutes anyway.

A hail of spit rains down on us throughout the set. Great gobs of phlegm land in my hair, my eyes and on my guitar neck, my fingers slide around as I try to hold down the chords. I look over at Ari and see spit land in her mouth as she sings. I don’t know if she gobs it back out or swallows it. I have to look down at my hands or I’ll lose my place. Someone in the front row tries to pull Ari off stage – we all stop playing and attack them – I hit them with my guitar, Palmolive beats them up, the bouncers haul them off with blood dripping down their faces and we start playing again.

It’s all over in a flash. We slam down our instruments and stalk off. A couple of beer cans come flying through the air and clunk onto the empty stage. Mick is waiting in the wings. ‘Well done,’ he says and kisses me. I’m high on adrenalin. That was great! Can’t wait to do it again tomorrow.

Straight after our set, Palmolive, Tessa, Ari and me pile out into the audience to watch Subway Sect. We dance around in front of the stage, people stare at us, they’ve never seen a band mingle with the audience before.

I remember seeing Subway Sect play at the Coliseum in Harlesden, the same night I saw the Slits for the first time. I was standing right at the front because if I’m interested in a band, I don’t act cool and stand at the back or in the VIP area, none of us do, we get down the front and watch like hawks, see what we can learn, read the signs, the attitude of the group. What are they saying? What’s their stance? What kind of energy do they have? Rob Symmons, Subway Sect’s guitarist, was so intense, he stood with his feet together, rooted to the spot, slightly knock-kneed. He wore his guitar really high, almost tucked under his armpit, and he strummed it so hard that his fingers bled and he dropped his plectrum, he just kept on playing with his fingers and there was blood all over his guitar. I wanted to pick up the plectrum and give it back to him, but I was too shy

.

After all the bands have played, we go to the hotel. First time I’ve stayed in a hotel. I unpack my suitcase and throw my clothes around the room.

The next morning on my way to breakfast, I see Chrissie Hynde come out of Paul Simonon’s room. Paul tells us later that last night Chrissie decided she didn’t want her tattoo any more (a dolphin I think) so they tried to scratch it off with a pumice stone. Then she read to him from the Bible. Sounds like such a sexy and sophisticated evening to me.

After breakfast, me, Ari, Tessa and Palmolive climb onto the official tour bus for the first time; Norman, the driver, gives us a dirty look. Yeah well, we’ve all seen that look before, we get it everywhere we go from men. There are just a few boys in the world who get us and they’re almost all on this bus. Norman scowls through the rear-view mirror at Ari: her skirt is so short her bum is showing, her hair’s backcombed so it looks like she’s had an electric shock, and she hugs a huge ghetto blaster under her arm which pumps out dub as she races up and down the aisle deciding who to sit next to.

Norman shouts at Ari to sit down, she takes no notice. Ari takes no notice of anyone, Norman doesn’t have a hope. He stomps off and refuses to get back on the bus whilst the Slits are on it. He tells Don – Don Letts has agreed to manage us for the

White Riot

tour – he’s not driving the Slits and we’ll have to find another way to get to Manchester. Here we go. Eventually it’s sorted out. He’s bribed to take us but still he has a condition –

The Slits don’t leave their seats until Manchester

. This is going to be impossible. Ari’s fifteen, she’s excited, there’s no way she’s going to be able to sit still until Manchester! And sure enough, after rocking back and forth to her mix tape for half an hour, she jumps up to dance in the aisle. Norman screeches to a halt.

‘The Slits must leave the bus.’

He’s bribed again and Ari is locked in the bog to keep her out of harm’s way. She doesn’t care, as long as she’s got her music with her. We’re all worried that if Norman discovers her age, he’ll tell the police and we’ll be kicked off the tour. She should be at school.

We arrive in Manchester. The Slits charge off the bus and explode into the hotel foyer like chickens released from the coop. Whilst Don checks us in, we drape ourselves over the chairs, Ari coughs up some phlegm and spits it onto the carpet. The manager looks up from his desk, clocks us – in a mixture of leather jeans, rubber dresses and knickers on top of our trousers, matted hair and smudged black eye makeup – pulls Don aside, and says, ‘They are not staying in this hotel.’

We have to go and find somewhere else to stay. But this hotel manager has called every hotel in Manchester ahead of us and no one wants us. (He got hold of the call sheet and contacted every hotel on the rest of the tour, telling them not to let us stay. So most nights we’re in a different hotel to the rest of the bands.) Eventually we find a B & B. Occasionally the Slits are allowed to stay at a nice hotel, if we go straight from the front door into the lift and stay in our rooms until morning. The hotel management don’t allow us to stand in the lobby, use the bar or come down to breakfast. No one must see us. We do not exist. Everywhere we go, we’re treated like we’re a threat to national security.