Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. (42 page)

Read Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. Online

Authors: Viv Albertine

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

To prove he’s right he records me singing and playing in his home studio, adds a bit of bass and drums, and when he’s mixed it, emails the track over to me. I rush upstairs to the computer in the bedroom and play the song. My voice is appallingly, sickeningly terrible. I can bear less than a minute before I shut it off. I’m crushed, he was wrong; my voice is awful and I can’t do it. I call Nelson in tears and say I’m not coming to the lessons ever again, I’ve faced the truth, I’m rubbish, I give up. Then I go to the doctor and get antidepressants. I don’t do this lightly. I’ve always been prone to depression, I’m melancholic, I’ve fought it all my life – last year it occurred to me to ask my mother, ‘Mum, does everyone have a knot of pain and anxiety in their chest every day, from the moment they wake up in the morning until they go to bed at night, like I do?’ She looked worried and said, ‘No.’

I can imagine the pain and stress that’s ahead of me now my marriage is falling apart and the stable family I’ve created for my daughter is disintegrating – I admit defeat. Give me the pills.

Nelson calls and persuades me to come over for one more lesson. When I get there he says, ‘I’m not going to teach you chords or scales any more, you have a unique guitar style and I don’t want to ruin it.’ It’s only because I trust Nelson with my whole heart that I believe him. I don’t believe in myself, but I believe in his belief in me. He continues, ‘I’m going to take you to some open mike sessions and get you playing live.’ He must be mad. I can’t stand up in front of people and play and sing. I would rather die.

Remember, Viv, the Year of Saying Yes

. So what if I die? So what if I’m crap and make a fool of myself? I know that no one ever does anything or gets anywhere without failure and foolishness. I’ve got to do it. Nelson has made me an offer I can’t refuse, the bugger.

I do have one other supporter: my eight-year-old daughter. My little girl, who has never seen her mother do anything except housework and being a wife, accepts me sitting down at the kitchen table every night and trying to learn to play guitar and write songs. She thinks it’s a wonderful thing for her mother to be doing. I involve her as much as I can in the process, asking her advice on lyrics, rhymes and middle eights. She’s very musical and I value her opinion. Then one day as I’m struggling with the bar chords I get frustrated and let go. I thrash at the guitar, zinging up and down the strings, strumming wildly. From this outburst comes a strange but very Viv-like riff – oriental, modal, lots of open strings ringing – and I know I’m back. My daughter looks up from her homework and with an emotional catch in her voice says, ‘Mummy, you were

born

to play guitar.’

That phrase, and the way she says it, sustains me for years.

19 BEL CANTO

2008

The better a singer’s voice, the harder it is to believe what they’re saying.

David Byrne

I feel ridiculous going to my studio to rehearse, plodding through the rain and greyness of Hastings, electric guitar slung on my back. What a fool, what a fraud. I trudge out of the car park, past the pound shop, through the underpass, glance sideways out of my hood at the thrashing waves and empty bus shelters; could it be any grimmer? Still, I’d rather be rebuilding myself in Hastings than anywhere else. I feel as if I am on the edge of the world here, or at least on the edge of England. This is a town that people come to when they want to get as far away from other people as possible. This is a town of renegades, musicians, writers, artists, drug takers, teenage mothers and pyromaniacs. It’s lawless, a frontier town, where anything goes and everything’s acceptable, even failure. I fucking love Hastings.

Andy Guinaire, a friend and brilliant pedal steel guitarist – who played with the Faces amongst others – comes to an open mike night and tells me to buy a better guitar. ‘That one sounds like you’re rattling a drawer full of cutlery.’ So I go and buy my first Telecaster for twenty-five years from Richard in Rye, a pink flower-print Fender Telecoustic.

I’m still going to the art school once a week, and I confide in Tony Bennett – the first person I say it out loud to – that my marriage is over. He looks unfazed and replies calmly that he sees marriages fall apart all the time amongst his students. He explains that it’s because you have to dig deep into yourself to make the work and you can’t help but get to know yourself better, who you really are and what you really want. It’s bound to have an impact all through your life.

I think back to Tony saying he recognised my voice when he heard me on the radio; I’ve always thought I have a very ordinary North London voice, but a few people have commented that the timbre of it is unusual. I don’t think they meant it in a good way, just that it’s a bit odd. Once when I was at a play centre with my daughter, a woman I hadn’t seen for ten years came up and said, ‘Is that you, Viv? I recognised your voice. You’ve got such a distinctive voice.’ I decide not to take it personally but to use this oddness in my voice and turn it to my advantage. I’m no chanteuse, but if I’m true to myself, true to ‘punk’ ethics and use my voice naturally and honestly, maybe it will be enough that it’s distinctive and personal like the songs. I start to let this idea roll around my mind. I go to the guitar shop, and this time I ask Richard if he knows a good singing teacher.

Sandra Scott. What a find. She lives in a black wood fisherman’s cottage, with a canary-yellow front door, on the edge of Rye. Every time I go in, I feel like I’m being gobbled up by a fat, squat blackbird with a yellow beak. I tell Sandra I don’t want to learn how to sing, I don’t want to sound mannered, I don’t want to change my voice in any way, I just want to learn how to open my mouth and let my voice come out. I’m so shy and scared that I can’t make a sound. I spend a lot of the lesson time sitting in front of the log fire crying. Winter turns to spring and as the seasons change, I fall apart in front of Sandra’s eyes and stitch myself back together again. She teaches me the bel canto method of projecting your voice through your nose and the front of your face using the chambers in your skull as resonators (‘singing into the mask’). Most untrained people sing from their throats, which gives no resonance, no warmth, and is very weak. With bel canto you can still use your voice even if you’re unwell, which is helpful because I always seem to have a cold.

I go to my studio every day and sing along with the exercise tape Sandra has given me. Up and down scales I go, that’s all I want to do. Not songs, just work the muscle that is my voice. Even though I’m on my own I don’t sing very loud, I stand with my back pressed against the white wall and make a tiny sound. Each day I make myself step further away from the wall until I have the confidence to stand in the middle of the room and project my voice all the way across, no longer caring if anyone is in the studio downstairs or what they think of me. I remember back to my squat in Davis Road, to the neighbours telling me to stop playing guitar, that it was unbearable to listen to, and how I got better, used my idiosyncrasies, made a great album. If I could turn my guitar playing around back then, surely I can turn my voice around now.

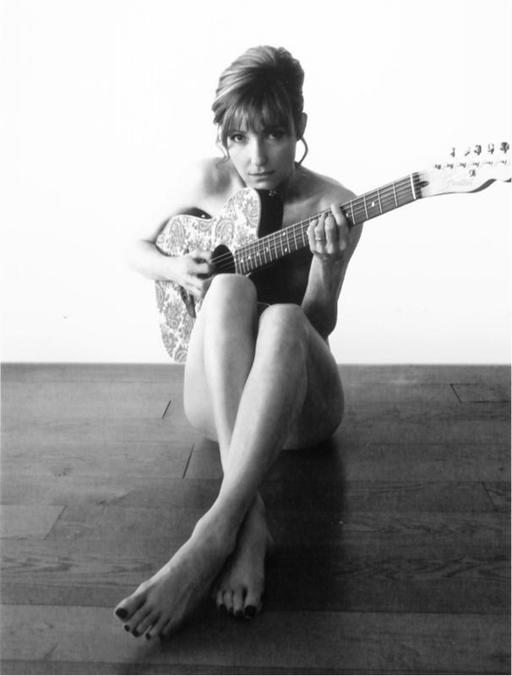

With new Fender Telecoustic

20 A MATTER OF DEATH AND LIFE

2008

What has to die in your life for what you are creating to be born?

Deepak Chopra

Midnight. I get out of the car and look up at the full moon. I feel so isolated and lonely that I talk out loud to it. ‘All right, Moon? Who else are you shining on? Anyone like me? Someone who might love me one day? Someone I’ll love?’

I lug my guitar up the path, past the spiky plants. During the day my daughter and I play around in the garden, running in and out of the bushes pretending they’re monsters, but at night they can do serious damage to your eyes or face as they claw at you in the dark. I can hear the sea crashing relentlessly on the shingle beach.

The reason I’m walking up the path to my house at midnight with a guitar is that twice a week I drive three hours to a random pub and three hours back home again, to play two of my songs in public. I spend all my spare moments in the days leading up to one of these open-mike nights choosing the two songs I’ll play.

Which ones can I play best? Which ones did I do last week? Which one first and which one second?

When I’ve made my choice, I practise the two songs over and over again for days.

Before I leave the house, I always make sure my daughter and husband are fed, that she’s put to bed and I’ve done the washing up. My husband is furious that I’m going out and thinks of more jobs I have to do before I leave. I do them, but eventually I pick up my guitar and make a break for it.

Ruby, don’t take your guitar to town.

During the long journey to the pub, I try to warm up my voice. The voice I have absolutely no confidence in. The voice I’ve been embarrassed about since I was a child – hating it so much that when I had to read a passage from the Bible out loud in assembly in the last year of primary school, I couldn’t do it. I just stood there, my body paralysed, my hands gripping the lectern, my mouth opening and closing like a dying guppy, thinking,

I can’t let them hear my voice, it’s so deep and ugly, like a boy’s

. I was frozen with fear. Eventually a kind teacher led me away.

The next time I dared use my voice was in the Slits – ‘punk’ was supposed to be open-minded and DIY but it was actually rigid and unforgiving and Ari was always very critical of our voices.

Driving along the coast road, singing along to the exercise tape, my voice sounds reedy and thin, sharp or flat, god knows which. I practise the lyrics, trying to memorise them, I think it looks terrible to have a sheet of paper in front of you when you sing. How is anyone going to believe you when you’re reading from a script?

I steer the Audi into the car park of an ugly pebble-dashed building and manoeuvre into a space, turn off the engine and sit back in my seat. Do I really want to do this? It’s not too late. I can turn the engine back on, reverse out of this place and drive home. I don’t have to put myself through the humiliation. But for some reason, I do have to. It’s like I’ve been taken over by an alien: I have no say in the matter. I get out, pull my guitar case out of the boot, put it on my back and walk mechanically up to the saloon-bar door. Inside my chest I have a heavy, bruised, sick feeling, like I’m going to the gallows.

I sit on my own at a sturdy dark brown wooden table, with a glass of mineral water on a beer mat in front of me, and my foot on the guitar case so nobody nicks my guitar. I think about Vincent, how he’s probably swanning around in Cannes or at the Chateau Marmont in LA. The bar’s half empty, a couple of older guys with expensive guitars sit strumming in the shadows. A tall skinny man with a grey ponytail leans against the bar blowing some blues riffs out of his harmonica: they’ve obviously all been playing for years. I study the sticky orange-and-brown patterned carpet, so I don’t catch anyone’s eye.

I make numerous trips to the bathroom and wash my hands over and over again because they’re sweaty with nerves. I look into the mirror and a nice, decent woman looks back, clean hair, lipstick, jeans, T-shirt. Middle-class. What the fuck is she doing in this godforsaken place with an electric guitar? Why isn’t she at home with her husband and child, watching TV? Vacuuming? Tidying up?

I hear my name announced and run back into the pub lounge, grab my Squier (the Telecoustic’s not very good live) and step up onto the small stage in the corner of the room. The MC tries to be helpful. ‘You a folk singer, love? Joni Mitchell, that sort of thing? This is where you plug in. Do you know how to use a mike? Have you turned the volume up on your guitar? It sounds a bit too trebly, here, let me turn the treble down a bit for you.’ He leans over and twiddles the knob on my guitar. I let him. My hands are shaking so badly that everyone can see.

I start to play. There are no monitors, the speakers are pointing away from me. I can’t hear what I’m singing but I can hear what I’m playing from the amp directly behind me, and it’s terrible. I’m embarrassingly awful. I am shit. But the songs are good. I know I’m crap, but I know the songs are good. And I have to get them out there somehow. They are little creatures clamouring to be heard. I’m compelled to do this. Beyond logic, beyond failure, beyond self-consciousness. There’s an older lady with a tatty woollen bobble hat on, leaning on the bar, staring into her whisky. She doesn’t look up. The guy with the ponytail smirks with his friends. There’s always someone laughing, sniggering, tutting. I shake with passion as the songs pour out. I make loads of mistakes, I sing wildly out of tune, I can’t look up from my fingers or I will miss the guitar strings. Every second is excruciating for me and for the audience. Six minutes later it’s all over. The compère jumps up and asks for applause for Viviane. He says kindly that it takes a lot of guts to get up and perform your own songs, that at least I’m not doing what everyone else does and playing cover versions. I unplug the guitar and walk through the tables to my seat. No one looks at me.