Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. (43 page)

Read Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. Online

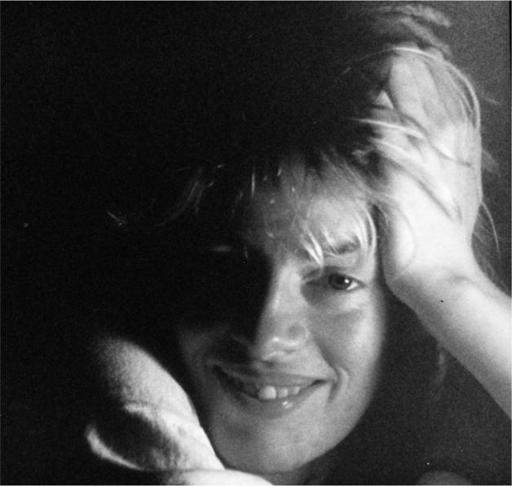

Authors: Viv Albertine

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

Something strange starts happening as I keep playing the open mike circuit. At every pub one or two people come up to me as I’m leaving – a fisherman, a farmer, the barman, another musician, a cool-looking girl – and say, ‘You know what? You really touched me. I know what you meant with those words. You’re the best thing I’ve seen in here.’ And once, out in the middle of nowhere, ‘You ever heard of a band called the Slits? You remind me of them.’ These people help me to keep going. They see past my incompetence to the honesty of the material.

I reach the front door to my house and fumble about in my bag, looking for my keys. The outside lights are turned off. All the lights in the house are turned off too, my husband’s gone to bed. Once inside I don’t dare turn on a light, I feel so guilty and wrong for what I’m doing that I’m as quiet as possible. I clean my teeth in the kitchen because the electric toothbrush is too noisy. I undress in darkness by the side of our bed and slide in. I try not to think about the humiliation that I’ve just suffered performing to a bunch of guys who can play the blues. I’d love to sit up with a cup of herbal tea and a piece of toast and chat and laugh about my experiences with my husband but he’s pretending to be asleep. I feel so lonely lying next to him, in this beautiful white house.

The blackness outside the windows stretches away into infinity. Not even an owl hoots. The weight of the silence is suffocating. The marriage is suffocating. Sadness and shock press down on my chest. We’ve been together for seventeen years. We’ve been through so much. We’ve been faithful to each other. We’ve always had a good sex life. We were so very much in love. But here we are, like two little children cold and lost in the woods, curled up, facing away from each other, blaming each other, and making our lifelong fears of abandonment come true.

21 THE NEW SLITS

2008

All I want to be able to do is sing and play three songs to a consistent standard and never drop below it, no matter how tired I am or how bad the PA is. At the moment I veer between passable and absolutely atrocious and this aspiration seems unattainable to me.

Nelson has to get on with his own life, he can’t keep coming to open mikes with me, but the thought of going to these pubs on my own twice a week is terrifying. For a lone female to walk into a pub – truck stop-type places some of them – in the middle of nowhere is a pretty daunting thing to do, but to stand up and play and sing your own bonkers songs, when everyone else is doing covers of ‘Chasing Cars’, is beyond brave, it’s madness. To make sure I don’t give up and because she believes in me, my friend Traci gets the train from London every time I play. I pick her up at Brighton, Hastings or whichever station is near the pub I’m going to that night, and she sits with me before I go on and giggles with me once I’ve come off. She’s a true friend.

I’m getting bolder, trying out different songs, talking to the audience, making jokes. When I play at a pub in Lewes in East Sussex, a guy called Tom Muggeridge comes up to me afterwards and says he really likes my songs, will I play at a festival he’s organising at Lewes Arts Lab in a couple of months’ time? My first gig. I get a band together with Tom on bass and a drummer and violinist from Brighton that I’ve met on my travels. We rehearse a couple of times in a warehouse. A few things go wrong on the night, but it’s a huge step forward and a thought pops into my mind as I’m up on stage:

I’m the singer

. I’ve made that transition from guitarist to front person, a massive leap for anyone in a band; if you start on an instrument, you never quite believe you’ve got what it takes to be the front person.

I don’t take shit any more when I play. One night in front of a crowd of braying ponytailed old rockers I shout, ‘Anyone here ever taken heroin? Made a record?’ There’s a stunned silence. ‘Well I have, so shut the fuck up or go home and polish your guitar.’ (They all had perfect, mint-condition guitars that you just know were only taken out of their cases once a week, polished and then put back to bed.) This time I don’t take the inevitable ‘too much treble’ comment from the compère. ‘It’s meant to be uncomfortable,’ I tell him and turn the treble up even more; I hope it hurts their ears. I begin to enjoy the tension between what the audience expects from a nice-looking woman and what they get – angry words and edgy guitar playing.

After a year and a half of playing open mikes, I’m in a large soulless modern pub in Brighton with an outside barbecue and a cocktail bar. I pour my heart out in my first song but no one takes any notice, they talk and laugh and shout. I’ve had enough; what I do doesn’t work as background music. I change the words of my next song to ‘Fuck, bollocks, cunt, shit, piss, wank’ – and every other swear word I can think of – and repeat them over and over again until eventually the whole room goes quiet. When I have their attention I say, ‘Thank you and goodnight.’ That’s the last open mike I play.

The New Slits gig is looming, I’m not nervous; what I’ve been doing in pubs for the last year, with a handful of people two inches from my face, playing my own material solo, is much more frightening than being on stage with a band. We go to Spain. It’s such good fun to be with Ari and Tessa again, and to have the camaraderie of a band. When we arrive at the hotel, we all hang out in one room, lounging across the beds and talking. There’s no group of women in the world that I have ever felt more completely at one with than Ari, Tessa and Palmolive (I wish Palmolive was here in the hotel room now), not just because of our shared history, but because we are all the same kind of woman. Ari talks about the trouble she’s having in Jamaica, how there’s a rumour going around Kingston that she’s a CIA spy and because some people believe it, they’re out to kill her. I don’t know how she can bear the amount of pressure she is constantly under, and has been under since she was fourteen, all for looking a bit different and doing her own thing without compromising. She asks me to look at a lump on her breast, says it’s been there for about a year. She knows I’ve had cancer and hopes I can give her some advice and reassurance. I touch it lightly, it’s pretty big, the size of an almond. I have no idea if it’s just a cyst or if it’s a tumour; I tell her she must go to a doctor as soon as we get back to England. She says she doesn’t like England, she’ll have it looked at in Jamaica.

At the venue we have a big dressing room, food is provided and there are monitors on the stage so we can hear ourselves, it’s all such a luxury to me. I love playing with the other musicians, I feel so much safer than I do when I’m solo. I feel a bit uncomfortable playing the songs though. The original Slits songs – although they stand the test of time musically – don’t resonate with me emotionally any more, not now I’m doing my own stuff. And the new songs, which are Jamaican-dancehall influenced, don’t resonate with me musically, even though they are really good. I can’t relate to the songs as a player, I’d rather be in the audience dancing to them and having a good time.

The next New Slits show is in Manchester. I take my daughter out of school so she can attend the concert, and I only need to look down from the stage at her in the front row, her eyes fixed on me with a look of such glowing pride, to know that I’ve done the right thing by her. If a mother or father ever gets to see such a look, just once in their lives, on their child’s face, they’ve as good as discovered the Holy Grail. During a dub section in the show, I play a couple of dissonant, abstract chords over the rhythm, but Ari runs over and shouts at me, ‘Stop playing! Stop playing!’ She hates it.

On the way back to London that night I look out of the car window at the motorway flashing past and decide I’m not going to play any more shows with the New Slits: I want to do my own thing. My little girl is curled up asleep with her head on my lap, I stroke her hair, I feel such love for her. I remember back to my love of the Slits twenty-five years ago, how devastated I was when it ended. I was like a dumped lover, I grieved for years but eventually I healed and hardened – not without scarring – because I had to. Ari made it impossible for the group to stay together, then years later she came back, like so many deserting lovers do; but for me, the time to make it work was then, not now.

Trace

22 FALLING APART

2009

You’re not an artist, you’re a wanker.

My husband

Husband issues an ultimatum,

Give up the music or that’s it

. I tell him he’s not asking me to choose between music and marriage, but life and death. So there is no choice. He thinks that by playing music I’m abandoning my family, welching on the deal (a deal that exists in his mind – I do the house stuff, he earns the money). I’m just a wanking, self-indulgent narcissist, a bad mother and a disappointing wife. He sounds like my father, ‘Don’t do it, don’t talk about it. Never mention it again.’ Except he goes a step further with ‘You’re useless, too old and what you’re doing is a waste of time.’ One afternoon, when a friend asks who I would like to be able to sing like and I answer, ‘Karen Carpenter,’ Husband guffaws with derision, spraying a mouthful of coffee across the table.

The two most important men in my life want me to deny who I am. As if it’s shameful. I can imagine a century ago they would have said,

If you don’t stop, I’ll commit you to a lunatic asylum

.

I keep trying to paint what I’m doing in a good light to my daughter, but Husband is taking away all her enthusiasm by turning my passion into negativity. I believe without a shadow of a doubt that I’m a good role model for her. To see your mother sit down and learn an instrument from scratch, write songs, and eventually be up on stage singing them is a fantastic lesson in making a dream come true. But my husband, who is ten years younger than me, is a child of the eighties and he doesn’t believe in hippy-dippy dreams coming true, he believes in earning money. I’m not making money. I may never make money doing this. He and I come from ideologically different times; I don’t judge him for that. He doesn’t want to support me financially or emotionally in this endeavour, I get that too.

I do something very unmotherly now, even though it feels as though I’m losing my daughter for the second time (the first time was after the cancer): I don’t stop concentrating on my music. I collect her from school, I make dinner, I put her to bed – I don’t tidy up, I don’t have time – I’m present most of the time physically, but not mentally. To make this huge step I have to immerse myself in my work. Just like all artists (wankers) have to immerse themselves in their work, just like Husband has immersed himself in his work for the past sixteen years. He’s stayed up all night figuring something out on the computer, sometimes for weeks on end. The difference is –

and it’s a big difference

– that he was earning money for the family. I’m not. I’m getting back on my feet and I’m contributing to the family in other ways, but what I’m doing right now can’t be measured in pounds and pence, and he’s a pounds and pence kind of guy. I liked that about him.

We go to a party, it’s full of couples we know. I look around the room and note that in every couple, one or both of the partners has had an affair, and yet here they all are, smiling and staying together. Husband and I have been faithful to each other and yet we are miserable and falling apart.

23 YES TO NOTHING

2009

Keith Levene is back in my life for the first time in twenty years; he’s considered a great guitarist now. I knew he was great, but I just thought he was great amongst us lot. It’s only recently that everything and everyone from back then is starting to be re assessed and often credited with influencing what’s happening in music today.

We meet up in the BFI bar on the Southbank. It’s as if we’ve never been apart. Immediate intimacy, deep talk, an emotional reunion, he sheds a tear. He really is an extraordinarily sensitive man. I tell him I’ve picked up the guitar again but I can’t play it very well. He says, ‘I’ll teach you, Viv.’ I’m so touched that Keith would help me again, even though it does seem to be a crazy thing to be doing, but he never was one to judge situations the way everyone else does.

And so I drive to East London once a week to play with Keith. The first time is excruciating. I’m scared of driving on motorways, I’ve lost confidence in every area of my life. When I get there, he says, ‘Let’s hear some of your songs then.’ I get out my guitar, plug it in and sing and play a bit of a song for him. He’s sitting about a foot in front of me. My voice shakes, my fingers stumble. But he gets it.

I’ve noticed a pattern forming in my life, it happens every time something doesn’t work out – a friendship, the New Slits, my marriage – if I have the courage to walk away from it rather than stay and cling on for fear of the unknown future, it seems to take from four to six months at the very most for something even better to manifest in front of me. I think of it as saying Yes to Nothing. If your choice is either the wrong thing or nothing, however frightened you are, you’ve got to take nothing. Haven’t you? Hasn’t everyone?