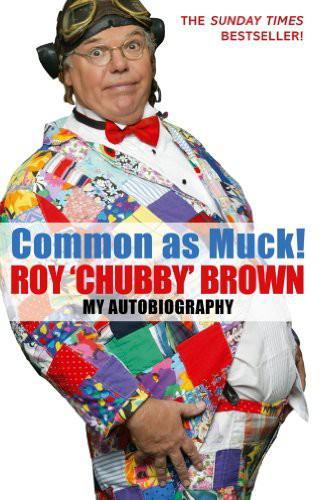

Common as Muck!: The Autobiography of Roy 'Chubby' Brown

Read Common as Muck!: The Autobiography of Roy 'Chubby' Brown Online

Authors: Roy Chubby Brown

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #General

Published by Hachette Digital

ISBN: 9781405520478

Copyright © Royston Vasey 2006

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a

retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior

permission in writing of the publisher.

Hachette Digital

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London, EC4Y 0DY

For Helen, Amy and Reece

CONTENTS

Copyright

Acknowledgements

Prologue: Blackpool Rock

Acknowledgements

Boys and girls, throughout this book I have been honest and frank, but in my heart I feel that some of the participants need to be protected by a change of name. I thank them all for adding value and colour to my life. And, last but not least, thanks to you, the great British public (wherever you are), for taking me to your hearts …

If there’s such a thing as reincarnation, can someone

please tell me before I give it all away.

I have been a Jack the lad but it’s better

than getting no cards on Father’s Day.

‘

YER FAT BASTARD!

’

Blackpool, July 2003. I’m on me home turf, the North Pier. It’s a glorious day and I’m passing through the amusement arcade at the start of the quarter-mile walk along the boards to the theatre at the end of the pier. I’m enjoying the warm summer sun and looking forward to the evening ahead. The show doesn’t start until seven-thirty and this is six o’clock, but I’m always in my dressing room early. It gives me time to soundcheck some songs and to rehearse a few new gags. Keith, my mate, is scuttling along beside me, carrying a Tesco shopping bag with a few cans of lager for before the show, when my good mood is shattered by a Glaswegian bellowing at full tilt.

Now, I know I’m a fat bastard without anyone telling me. After all, it’s my catchphrase, one that, in less than two hours’ time, more than 1,500 punters will be chanting as I come on stage. But some people go too far.

‘Oi, you! Yes, you!’ It’s the Glaswegian again. ‘

You big fat cunt!

‘

I turn around. There, in the dead area between the hot-dog

stall, the gift shop, the rock shop and the stall selling T-shirts with plastic tits on them, a lump of shite is sitting at a table. Nearby, there’s a gang of lads who’ve got tickets to come and see me. They’re standing at the bar, downing a few jars, getting blathered before the show and starting to take an interest in the rude fucker shouting his mouth off.

I can see he is what us Teessiders call a hacky get – a miserable, filthy waste of space. But he’s a hacky get with a family, so I know to behave. There’s his wife and his three little kids to consider. They’re about nine, eight and six, I’d guess, and I don’t want to upset them.

I haven’t had a proper fight in more than ten years. I’ve learned to keep my hands to myself. I don’t want to reawaken bad habits, so I ignore him and keep walking, my eyes fixed straight ahead.

‘Oi! I’m talking to

you

, you big

fat

bastard,’ the Glaswegian hollers again. I turn around and stare him down.

‘Why don’t you just grow up?’ I say. And I keep walking.

‘Ah, fuck off!’ The Glaswegian is obviously not going to give up easily.

I stop walking and slowly turn around, my temper rising inside me like a kettle coming to the boil. From the way that he’s carrying on, it’s clear to me that he’s got no respect for his wife or his kids. He’s certainly got no respect for all the people around him. Every table in the bar is taken and they’re all staring our way, wondering what’s going on. I want to give the lanky lout a bat, show him that I might be fat and I might be old enough to be his grandfather, but that I won’t be spoken to like that. But instead I ignore him and head for the door.

Just as I pass through the door he shouts again. ‘

Fuck you

, you fucking

fat cunt

.’

It’s too much. ‘I’m not putting up with this,’ I mutter to Keith.

‘You what?’ Keith replies.

‘I said that sackless nowt’s taken a right fucking lend of me.’ And I turn on my heels. ‘I’m gonna have to ploat that cunt.’

I walk up to him. ‘Have you got something to say to me?’

‘Ahh, you’re a big cunt!’

For a moment I don’t know what to do. This kind of thing happens to me almost every day and it’s a finely judged thing to get it right. Do I take offence or do I let it wash over me? After all, most of the time it’s harmless. Just a couple of fans who don’t know what to say and think it’s okay to be rude. Because I swear and talk about tits, fannies and cocks on stage they think that they can insult me in the street. Like the little old lady who stopped me in my tracks on Blackpool South Pier fifteen years ago. She was in her early seventies and with a man I assumed was her husband. They looked like any other elderly couple, enjoying the sea air and taking in the Golden Mile.

‘Eeeh,’ she said. And she put her hand on my chest to stop me. ‘Eeeh, you fat bastard.’

So I stopped walking. ‘Yes?’ I said, smiling.

‘Eeeh, you fat bastard,’ she said again. Then she giggled. ‘Hee hee, you fucking fat bastard.’ By now, the shock element had gone. I was looking at this elderly woman and thinking two things. First, that’s a foul mouth you’ve got on you, especially for a woman of your age. And second, what are you going to say next? I know I’m a fat bastard. Right?

After the fifth or sixth ‘fat bastard’, I said: ‘Now you’ve recognised me, what do you want?’

‘Eeeh, I think you’re fucking great, you fat bastard. Eeeh, you fucking fat bastard.’

I walked off, half in despair and half in frustration. What else could I do? If I had said owt, she would have thought I was the rude one. I couldn’t win.

And it’s not just old ladies. One evening, on the way to work,

a little girl walked up to me. With blonde hair and blue eyes, she was no more than six or seven years old and absolutely gorgeous. If you ever wanted to paint a picture of a perfect little girl, she would have been it.

‘Hello,’ I said, smiling at her and glancing at her parents standing nearby.

‘Hello,’ she replied bashfully. ‘You’re a fat bastard, aren’t you?’

‘Am I?’ I said.

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘You’re a big fat bastard.’ And she looked around at her parents, who were smiling, beaming with pride at their daughter’s cheek. What kind of parent tells their six-year-old child to go up to a complete stranger and insult them? If I had ever sworn in front of my father, he would have lifted me so high the weather would have changed by the time I got back down.

Now I can’t tell people how to lead their lives and most of my fans are just great. But there’s always the idiot who thinks it’s fine to shout ‘Hiya, Chubby, you big fat cunt’ down a supermarket aisle when I’m doing my shopping. It makes me cringe with embarrassment as all the other shoppers stare at me. I can see what they’re thinking: if he wasn’t here, we wouldn’t be hearing that. Or maybe they think that I’m the kind of person who sits in a restaurant and orders their food by saying to the waiter: ‘I’ll have the steak and chips, cunt face’. But I’m not and I never have been. And now, standing in the North Pier bar at Blackpool, I’ve had enough.

‘If you are gonna say sommat to me, will you say it to me outside the bar, please?’ I say.

The muscles in the Glaswegian’s face tighten as I grab him by his T-shirt and wrap my fist around it. I pull him off his chair and drag him thirty feet to the door.

‘I’ll fucking kill you, you fat bastard,’ he screams as I skid him across the sticky floor. ‘I’ll fucking glass you.’

‘Yes, I know you will,’ I say. The bar is silent. Everybody is watching. The customers in the gift shops stop in their tracks and come out of the shops to have a stare. People eating ice creams stand open-mouthed, watching what is going on.

‘Now what are you gonna fucking say?’ I snarl as we get outside and I pull him to his feet, pushing him across the boardwalk to the edge of the pier.

The Glaswegian is unsteady, so I see the swing of his fist coming towards me long before it’s within range. I dodge the punch, turn him around and dig him once in the ribs. He goes down like a sack of shite, then jumps up.

‘I’ll fucking kill you!’ he shouts as Keith grabs him. ‘I’m gonna kill him. I’m gonna fucking kill the fat fucker,’ he shouts, kicking Keith at the same time.

‘You’ll kill no fucker, else I’ll throw you over the fucking side, you twat,’ I shout. And I mean it. I want to give him a lacing, but Keith has him pinned down on the floor as three security guards come pounding down the pier and grab the lanky Glaswegian. With Keith and the bouncers between us, the Glaswegian tries to throw a few punches but he can’t get near me.

‘I wouldn’t if I was you, mate,’ Keith says. ‘I wouldn’t.’

The Glaswegian is carted away and I head for the theatre. An hour later, I’m on stage. The show’s going well. It’s always a buzz to play Blackpool and I’m more pumped up than usual, the adrenalin from the earlier aggro sharpening my timing and delivery. I leave the stage to a standing ovation and close the door to the dressing room. The first few minutes after any show are always the hardest. The silence after the noise and the adoration of the crowd is particularly lonely. Mulling over the performance, over-analysing the audience’s response to new routines, I sip a cup of tea while the punters file out of the auditorium and into the night.

There’s a knock at the door. Probably Richie, the tour manager, I think. Letting me know that some fans are waiting for an autograph at the stage door. Or maybe some friends have come backstage and want to say hello.

‘Mr Vasey?’ says a voice on the other side of the door. ‘Could you please open the door.’

Two policemen are standing in the corridor. They charge me with common assault and require me to appear at the police station. The next morning I am arrested, fingerprinted, relieved of the contents of my pockets, my belt and my shoelaces, and led down to the cells.

The Glaswegian, the coppers tell me, is a heroin addict. He’s in Blackpool at the council’s expense for a weekend’s rehabilitation with his children and wife, who had previously had a court order against him because of his violent behaviour. He provoked me and threw the first punch, yet

I

am being charged.

A month later I am in court. The police have dropped their charges, but I am fined two hundred pounds and ordered to pay seventy quid costs and eighty pounds compensation to the Glaswegian for ripping a T-shirt that looked like it cost no more than a fiver. I am recovering from recent throat-cancer operations and my wife is expecting our second child in the next fortnight, but that’s not taken into account by the magistrates. My reputation goes before me and I have to face the consequences.

I am not particularly proud of what I did, so why do I mention it? Because it’s what this book is about – what it’s like to be Britain’s rudest, crudest, most controversial comic, and what it’s like to live with the consequences of that reputation. But most of all, it’s about where that rudeness, crudity and appetite for controversy came from. I’ve come a long way since I grew up in the toughest of Middlesbrough’s grimmest neighbourhoods, but Grangetown still runs through me like the lettering in a

stick of Blackpool rock and I can’t escape it. In the end, I suppose, it’s about how you can take the lad out of Grangetown but you can’t take Grangetown out of the lad. Grangetown is why I became Britain’s foulest-mouthed comic. It drove me to escape a dead-end no-hope future. A hard life on its streets made me fearless. And if you come from where I did, it doesn’t take much to change your opening line from ‘Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. I’m the son of a bricklayer’s labourer. My mother had to take any job when the war was on’ to ‘Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. My wife’s got two cunts and I’m one of them.’