Complete Stories (4 page)

Authors: Dorothy Parker,Colleen Bresse,Regina Barreca

Bunkers, Suzanne L. “ ‘I am Outraged Womanhood’: Dorothy Parker as Feminist and Social Critic.”

Regionalism and the Female Imagination

4 (1978): 25-35.

Regionalism and the Female Imagination

4 (1978): 25-35.

Douglas, George.

Women of the Twenties

. New York: Saybrook, 1989.

Women of the Twenties

. New York: Saybrook, 1989.

Gray, James. “Dream of Unfair Women: Nancy Hale, Clare Booth Luce, and Dorothy Parker.” In James Gray,

On Second Thought

. Minne apolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1946.

On Second Thought

. Minne apolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1946.

Hagopian, John. “You Were Perfectly Fine.”

Insight I: Analyses of American Literature

. Frankfurt: A. M. Hirschgraben, 1962.

Insight I: Analyses of American Literature

. Frankfurt: A. M. Hirschgraben, 1962.

Labrie, Ross. “Dorothy Parker Revisited.”

Canadian Review of American Studies

7 (1976): 48-56.

Canadian Review of American Studies

7 (1976): 48-56.

Kinney, Arthur F.

Dorothy Parker

. Boston: Twayne, 1978.

Dorothy Parker

. Boston: Twayne, 1978.

Miller, Nina. “Making Love Modern: Dorothy Parker and Her Public.”

American Literature

64, no. 4 (1992): 763-784.

American Literature

64, no. 4 (1992): 763-784.

Shanahan, William. “Robert Benchley and Dorothy Parker: Punch and Judy in Formal Dress.”

Rendevous

3, no. 1 (1968): 23-34.

Rendevous

3, no. 1 (1968): 23-34.

Toth, Emily. “Dorothy Parker, Erica Jong, and New Feminist Humor.”

Regionalism and the Female Imagination

2, no. 2 (1977): 70-85.

Regionalism and the Female Imagination

2, no. 2 (1977): 70-85.

Trichler, Paula A. “Verbal Subversions in Dorothy Parker: ‘Trapped Like a Trap in a Trap.’ ”

Language and Style: An International Journal

13, no. 4 (1980): 46-61.

Language and Style: An International Journal

13, no. 4 (1980): 46-61.

Walker, Nancy. “Fragile and Dumb: The ‘Little Woman’ in Woman’s Humor, 1900-1940.”

Thalia: Studies in Literary Humor

5 (1982), no. 2: 24-49.

Thalia: Studies in Literary Humor

5 (1982), no. 2: 24-49.

Yates, Norris. “Dorothy Parker’s Idle Men and Women.” In Norris Wilson Yates,

The American Humorist: Conscience of the Twentieth Century

. Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1964.

BACKGROUNDThe American Humorist: Conscience of the Twentieth Century

. Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1964.

Capron, Marion. “Dorothy Parker.”

Writers at Work: The Paris Review Interviews

. Edited by Malcolm Cowley. New York: Viking, 1957. Reprinted in

Women Writers at Work

. Edited by George Plimpton. New York: Penguin, 1989.

Writers at Work: The Paris Review Interviews

. Edited by Malcolm Cowley. New York: Viking, 1957. Reprinted in

Women Writers at Work

. Edited by George Plimpton. New York: Penguin, 1989.

Case, Frank.

Tales of a Wayward Inn

. New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1938.

Tales of a Wayward Inn

. New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1938.

Douglas, Ann.

Terrible Honesty: Mongrel Manhattan in the 1920s

. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1995.

Terrible Honesty: Mongrel Manhattan in the 1920s

. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1995.

Drennan, Robert, ed.

The Algonquin Wits

. New York: Citadel Press, 1968.

The Algonquin Wits

. New York: Citadel Press, 1968.

Gaines, James R.

Wit’s End: Days and Nights of the Algonquin Round Table

. New York: Harcourt, 1977.

Wit’s End: Days and Nights of the Algonquin Round Table

. New York: Harcourt, 1977.

Grant, Jane.

Ross, The New Yorker, and Me

. New York: Raynel & Morrow, 1968.

Ross, The New Yorker, and Me

. New York: Raynel & Morrow, 1968.

Harriman, Margaret Case.

The Vicious Circle: The Story of the Algonquin Round Table

. New York: Harcourt, 1977.

The Vicious Circle: The Story of the Algonquin Round Table

. New York: Harcourt, 1977.

Kramer, Dale.

Ross and The New Yorker

. New York: Doubleday, 1951.

Ross and The New Yorker

. New York: Doubleday, 1951.

Kunkel, Thomas.

Genius at Work: Harold Ross of The New Yorker

. New York: Random House, 1995.

DOROTHY PARKER BIOGRAPHIESGenius at Work: Harold Ross of The New Yorker

. New York: Random House, 1995.

Frewin, Leslie.

The Late Mrs. Dorothy Parker

. New York: Macmillan, 1986.

The Late Mrs. Dorothy Parker

. New York: Macmillan, 1986.

Keats, John.

You Might As Well Live: The Life and Times of Dorothy Parker

. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1970.

You Might As Well Live: The Life and Times of Dorothy Parker

. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1970.

Meade, Marion.

Dorothy Parker: What Fresh Hell Is This?

New York: Villard Books, 1988.

ANTHOLOGYDorothy Parker: What Fresh Hell Is This?

New York: Villard Books, 1988.

The Viking Portable Library: Dorothy Parker

. New York: Viking, 1944. Republished as

The Indispensable Dorothy Parker

. New York: Book Society, 1944. Published again as

Selected Short Stories

. New York: Editions for the Armed Services, 1944. Revised and enlarged as

The Portable Dorothy Parker

. New York: Viking, 1973; revised, 1976. Republished as

The Collected Dorothy Parker

. London: Duck-worth, 1973.

. New York: Viking, 1944. Republished as

The Indispensable Dorothy Parker

. New York: Book Society, 1944. Published again as

Selected Short Stories

. New York: Editions for the Armed Services, 1944. Revised and enlarged as

The Portable Dorothy Parker

. New York: Viking, 1973; revised, 1976. Republished as

The Collected Dorothy Parker

. London: Duck-worth, 1973.

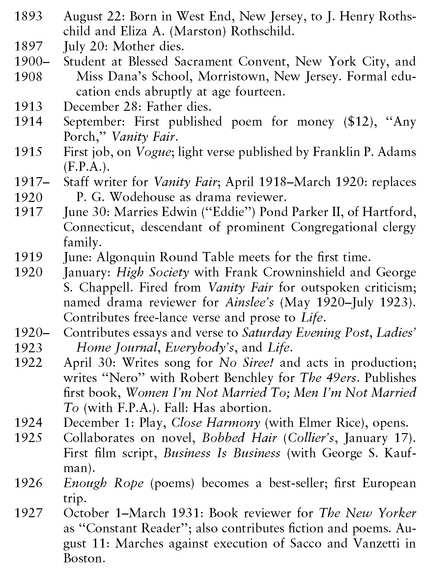

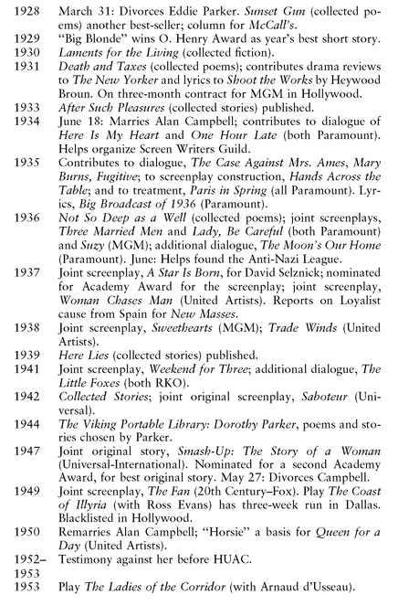

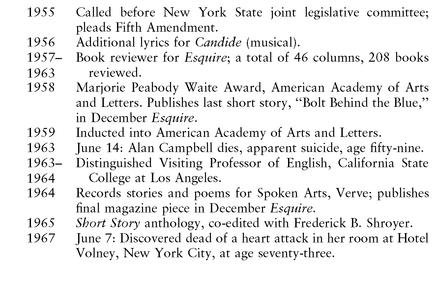

CHRONOLOGY

A NOTE ON THE TEXT

The stories are republished here from the texts of their original sources except in those instances where Dorothy Parker herself emended them in subsequent collections. The original sources are noted at the end of each story; variants and emendations are noted below. Minor orthographic emendations have been silently incorporated throughout the collection.

“The Wonderful Old Gentleman” (1926) was originally subtitled “A Story Proving that No One Can Hate Like a Close Relative.” The subtitle was dropped when the story was first collected in

Laments for the Living

(1930) and subsequently in

The Viking Portable Library: Dorothy Parker

(1944).

Laments for the Living

(1930) and subsequently in

The Viking Portable Library: Dorothy Parker

(1944).

“Lucky Little Curtis” (1927) was retitled simply “Little Curtis” in

Laments for the Living

and thereafter in the

Portable

.

Laments for the Living

and thereafter in the

Portable

.

“Long Distance” (1928), subtitled “Wasting Words, or an Attempt at a Telephone Conversation Between New York and Detroit,” was retitled “New York to Detroit” in

Laments for Living

and in the

Portable

.

Laments for Living

and in the

Portable

.

“The Waltz” (1933): The $50 figure at the end of the story was retained in Parker’s collection

After Such Pleasures

(1933) but changed to $20 in Parker’s

Here Lies

(1939) and the

Portable

.

After Such Pleasures

(1933) but changed to $20 in Parker’s

Here Lies

(1939) and the

Portable

.

“The Custard Heart” first appeared in

Here Lies

(1939). Unlike her other stories, there was no original magazine publication.

Here Lies

(1939). Unlike her other stories, there was no original magazine publication.

“The Game” (1948) was co-authored by Ross Evans, Parker’s collaborator on the play

The Coast of Illyria

(1949).

The Coast of Illyria

(1949).

STORIES

Such a Pretty Little Picture

Mr. Wheelock was clipping the hedge. He did not dislike doing it. If it had not been for the faintly sickish odor of the privet bloom, he would definitely have enjoyed it. The new shears were so sharp and bright, there was such a gratifying sense of something done as the young green stems snapped off and the expanse of tidy, square hedge-top lengthened. There was a lot of work to be done on it. It should have been attended to a week ago, but this was the first day that Mr. Wheelock had been able to get back from the city before dinnertime.

Clipping the hedge was one of the few domestic duties that Mr. Wheelock could be trusted with. He was notoriously poor at doing anything around the house. All the suburb knew about it. It was the source of all Mrs. Wheelock’s jokes. Her most popular anecdote was of how, the past winter, he had gone out and hired a man to take care of the furnace, after a seven-years’ losing struggle with it. She had an admirable memory, and often as she had related the story, she never dropped a word of it. Even now, in the late summer, she could hardly tell it for laughing.

When they were first married, Mr. Wheelock had lent himself to the fun. He had even posed as being more inefficient than he really was, to make the joke better. But he had tired of his helplessness, as a topic of conversation. All the men of Mrs. Wheelock’s acquaintance, her cousins, her brother-in-law, the boys she went to high school with, the neighbors’ husbands, were adepts at putting up a shelf, at repairing a lock, or making a shirtwaist box. Mr. Wheelock had begun to feel that there was something rather effeminate about his lack of interest in such things.

He had wanted to answer his wife, lately, when she enlivened some neighbor’s dinner table with tales of his inadequacy with hammer and wrench. He had wanted to cry, “All right, suppose I’m not any good at things like that. What of it?”

He had played with the idea, had tried to imagine how his voice would sound, uttering the words. But he could think of no further argument for his case than that “What of it?” And he was a little relieved, somehow, at being able to find nothing stronger. It made it reassuringly impossible to go through with the plan of answering his wife’s public railleries.

Mrs. Wheelock sat, now, on the spotless porch of the neat stucco house. Beside her was a pile of her husband’s shirts and drawers, the price-tags still on them. She was going over all the buttons before he wore the garments, sewing them on more firmly. Mrs. Wheelock never waited for a button to come off, before sewing it on. She worked with quick, decided movements, compressing her lips each time the thread made a slight resistance to her deft jerks.

She was not a tall woman, and since the birth of her child she had gone over from a delicate plumpness to a settled stockiness. Her brown hair, though abundant, grew in an uncertain line about her forehead. It was her habit to put it up in curlers at night, but the crimps never came out in the right place. It was arranged with perfect neatness, yet it suggested that it had been done up and got over with as quickly as possible. Passionately clean, she was always redolent of the germicidal soap she used so vigorously. She was wont to tell people, somewhat redundantly, that she never employed any sort of cosmetics. She had unlimited contempt for women who sought to reduce their weight by dieting, cutting from their menus such nourishing items as cream and puddings and cereals.

Adelaide Wheelock’s friends—and she had many of them—said of her that there was no nonsense about her. They and she regarded it as a compliment.

Sister, the Wheelocks’ five-year-old daughter, played quietly in the gravel path that divided the tiny lawn. She had been known as Sister since her birth, and her mother still laid plans for a brother for her. Sister’s baby carriage stood waiting in the cellar, her baby clothes were stacked expectantly away in bureau drawers. But raises were infrequent at the advertising agency where Mr. Wheelock was employed, and his present salary had barely caught up to the cost of their living. They could not conscientiously regard themselves as being able to afford a son. Both Mr. and Mrs. Wheelock keenly felt his guilt in keeping the bassinet empty.

Sister was not a pretty child, though her features were straight, and her eyes would one day be handsome. The left one turned slightly in toward the nose, now, when she looked in a certain direction; they would operate as soon as she was seven. Her hair was pale and limp, and her color bad. She was a delicate little girl. Not fragile in a picturesque way, but the kind of child that must be always undergoing treatment for its teeth and its throat and obscure things in its nose. She had lately had her adenoids removed, and she was still using squares of surgical gauze instead of handkerchiefs. Both she and her mother somehow felt that these gave her a sort of prestige.

Other books

Their Ex's Redrock Dawn (Texas Alpha Biker) by Shirl Anders

Baby Momma Drama by Weber, Carl

Garden of the Moon by Elizabeth Sinclair

West of the Moon by Katherine Langrish

Random Targets by James Raven

The Jersey Devil by Hunter Shea

18% Gray by Anne Tenino

Greyrawk (Book 2) by Jim Greenfield

Blackwater: The Complete Caskey Family Saga by McDowell, Michael