Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453 (35 page)

Read Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453 Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

He then laid out the tactics for the battle. He believed, quite rightly, that the defenders were exhausted by constant bombardment and skirmishing. The time had come to bring the full advantage of numbers into play. The troops would attack in relays. When one division was exhausted, a second would replace it. They would simply hurl wave after wave of fresh troops at the wall until the weary defenders cracked. It would take as long as it took and there would be no let-up: ‘once we have started fighting, warfare will be unceasing, without sleeping or eating, drinking or resting, without any let-up, with us pressing on them until we have overpowered them in the struggle’. They would attack the city from all points simultaneously in a co-ordinated onslaught, so that it was impossible for the defenders to move troops to relieve particular pressure points. Despite the rhetoric, limitless attack was impossible: the practical timeframe for a full-scale assault would be finite, compressed into a few hours. A stout resistance would inflict murderous slaughter on the rushing troops; if they failed to overwhelm the defenders quickly, withdrawal would be inevitable.

Precise orders were given to each commander. The fleet at the Double Columns was to encircle the city and tie down the defenders at the sea walls. The ships inside the Horn were to assist in floating the pontoon across the Horn. Zaganos Pasha would then march his troops across from the Valley of the Springs and attack the end of the land wall. Next, the troops of Karaja Pasha would confront the wall by the Royal Palace, and in the centre Mehmet would station himself with Halil and the Janissaries for what many considered to be the crucial theatre of operations – the shattered wall and the stockade in the Lycus valley. On his right Ishak Pasha and Mahmut Pasha would

attempt to storm the walls down towards the Sea of Marmara. Throughout he laid particular emphasis on ensuring the discipline of the troops. They must obey commands to the letter: ‘to be silent when they must advance without noise, and when they must shout to utter the most bloodcurdling yells’. He reiterated how much hung on the success of the attack for the future of the Ottoman people, and promised personally to oversee it. With these words he dismissed the officers back to their troops.

Later he rode in person through the camp, accompanied by his Janissary bodyguard in their distinctive white headdresses, and his heralds who made the public announcement of the coming attack. The message cried amongst the sea of tents was designed to ignite the enthusiasm of the men. There would be the traditional rewards for storming a city: ‘You know how many governorships are at my disposal in Asia and in Europe. Of these I will give the finest to the first to pass the stockade. And I shall pay him the honours which he deserves, and I shall requite him with a position of wealth, and make him happy among the men of our generation.’ All major Ottoman battles were preceded by the promise of a graduated series of stated honours designed to spur the men on. There was a matching set of punishments: ‘But if I see any man lurking in the tents and not fighting at the wall, he will not be able to escape a lingering death.’ It was one of the psychological ploys of Ottoman conquest that it bound men into an effective reward system that linked honour and profit to the recognition of exceptional effort. It was implemented by the presence on the battlefield of the sultan’s messengers, the

chavushes

, a body of men who reported directly to the sultan. Their single account of an act of bravery could lead to instant promotion. The men knew that great acts could be rewarded.

Mehmet went further. In accordance with the dictates of Islamic law, it was decreed that since the city had not surrendered it would be given to the soldiers for three days of plunder. He swore by God, ‘by the four thousand prophets, by Muhammad, by the soul of his father and his children and by the sword he strapped on, that he would give them everything to sack, all the people, men and women, and everything in the city, both treasure and property, and that he would not break his promise’.

The prospect of the Red Apple, rich in plunder and marvels, was a direct appeal to the very soul of the nomadic raider, an archetype of

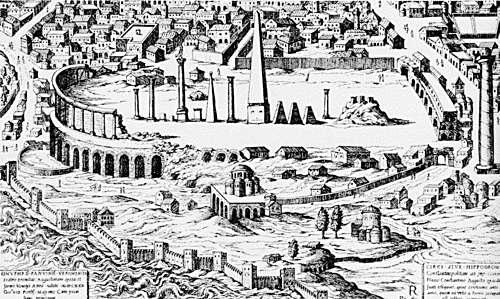

the horseman’s longing for the wealth of cities. After seven weeks of suffering in the spring rain it must have struck the men with the force of hunger. To a large extent the city they imagined did not exist. The Constantinople conjured by Mehmet had been ransacked by Christian crusaders two and a half centuries earlier. Its fabulous treasures, its gold ornaments, its jewel-encrusted relics had largely gone in the catastrophe of 1204 – melted down by Norman knights or shipped off to Venice with the bronze horses. What was left in May 1453 was an impoverished, shrunken shadow of its former self, whose main wealth was now its people. ‘Once the city of wisdom, now a city of ruins,’ Gennadios had said of the dying Constantinople. A few rich men may have had hoards of gold hidden in their houses and the churches still had precious objects, but the city no longer possessed the treasure troves of Aladdin that the Ottoman troops longingly imagined as they stared up at the walls.

City of ruins: the crumbling hippodrome and empty spaces of the city

Nevertheless the proclamation whipped the listening army into a fever of excitement. Their great shouts were carried to the exhausted defenders watching from the walls. ‘O, if you had heard their voices raised to heaven,’ recorded Leonard, ‘you would indeed have been paralysed.’ The looting of the city was probably a promise that Mehmet had not wanted to make, but it had become the necessary

lever for fully winning over the grumbling troops. A negotiated surrender would have prevented a level of destruction that he was hoping to avoid. The Red Apple was not for Mehmet just a chest of war booty to be plundered; it was to be the centre of his empire and he was keen to preserve it intact. With this in mind a stern caveat was attached to the promise: the buildings and walls of the city were to remain the property of the sultan alone; under no circumstances were they to be damaged or destroyed once the city had been entered. The capture of Istanbul was not to be a second sacking of Baghdad, the most fabulous city of the Middle Ages, committed to the flames by the Mongols in 1258.

The attack was fixed for the day after next – Tuesday 29 May. In order to work the soldiers to a pitch of religious zeal and to quash any negative thoughts, it was announced that the following day, Monday 28, was to be given over to atonement. The men were to fast during daylight hours, to carry out their ritual ablutions, to say their prayers five times and to ask God’s aid in capturing the city. The customary candle illuminations were to continue for the next two nights. The mystery and awe that the illuminations, combined with prayers and music, worked on both the men and their enemies were powerful psychological tools, employed to full effect outside the walls of Constantinople.

In the meantime the work in the Ottoman camp went on with renewed enthusiasm. Vast quantities of earth and brushwood were collected ready to fill up the ditch, scaling ladders were made, stockpiles of arrows were collected, wheeled protective screens drawn up. As night fell the city was again ringed by a brilliant circle of fire; the rhythmic chanting of the names of God rose steadily from the camp to the steady beating of drums, the clash of cymbals and the skirl of the

zorna

. According to Barbaro the shouting could be heard across the Bosphorus on the coast of Anatolia, ‘and all us Christians were in the greatest terror’. Within the city it had been the feast day of All Saints, but there was no comfort in the churches, only penitence and continual prayers of intercession.

At the day’s end Giustiniani and his men again set about repairing the damage to the outer wall, but in the brilliantly illuminated darkness the cannon fire continued unabated. The defenders were horribly conspicuous and it was now, according to Nestor-Iskander, that Giustiniani’s personal luck started to run out. As he directed operations, a fragment of stone shot, probably a ricochet, struck the

Genoese commander, piercing his steel breastplate and lodging in his chest. He fell to the ground and was carried home to bed.

It is difficult to overestimate the importance of Giustiniani to the Byzantine cause. From the moment that he had stepped dramatically onto the quayside in January 1453 with 700 skilled fighters in shining armour, Giustiniani had been an iconic figure in the defence of the city. He had come voluntarily and at his own expense, ‘for the advantage of the Christian faith and for the honour of the world’. Technically skilful, personally brave and utterly tireless in his defence of the land walls, he alone had been able to command the loyalty of both the Greeks and Venetians – to the extent that they were forced to make an exception to their general hatred of the Genoese. The construction of the stockade was a brilliant piece of improvisation whose effectiveness chipped away at the morale of the Ottoman troops. The unreliable testimony of his fellow countryman, Leonard of Chios, suggests that Mehmet was moved to exasperated admiration of his principal opponent and tried to bribe him with a large sum of money. Giustiniani was not to be bought. Despair seems to have gripped the defenders at the felling of their inspirational leader. Wall repairs were abandoned in disarray. When Constantine was told, ‘right away his resolution vanished and he melted away into thought’.

At midnight the shouting again suddenly died down and the fires were extinguished. Silence and darkness fell abruptly over the tents and banners, the guns, horses and ships, the calm waters of the Horn and the shattered walls. The doctors who watched over the wounded Giustiniani ‘treated him all night long and laboured in sustaining him’. The people of the city enjoyed little rest.

Mehmet spent Monday 28 May making final arrangements for the attack. He was up at dawn giving orders to his gunners to prepare and aim their guns on the wrecked parts of the wall, so that they might target the vulnerable defenders when the order was given later in the day. The leaders of the cavalry and infantry divisions of his guard were summoned to receive their orders and were organized into divisions. Throughout the camp the order was given, to the sound of trumpets, that all the officer corps should stand to their posts under pain of death, in readiness for tomorrow’s attack.

When the guns did open up, ‘it was a thing not of this world’, according to Barbaro, ‘and this they did because it was the day for

ending the bombardment’. Despite the intensity of the cannon fire there were no attacks. The only other visible activity was the steady collection of thousands of long ladders, which were carried up close to the walls, and a huge number of wooden hurdles, which would provide protection for the advancing men as they struggled to climb the stockade. Cavalry horses were brought in from pasture. It was a late spring day and the sun was shining. Within the Ottoman camp the men went about their preparations: fasting and prayer, sharpening blades, checking fastenings on shields and armour, resting. A mood of introspection stilled the troops as they steadied themselves for the final assault. The religious quietness and discipline of the army unnerved the watchers on the walls. Some hoped that the lack of activity was a preparation for withdrawal; others were more realistic.

Mehmet had worked hard on the morale of his men, tuning their responses over several days through cycles of fervour and reflection that were designed to build morale and distract from internal doubt. The mullahs and dervishes played a key role in creating the right mentality. Thousands of wandering holy men had come to the siege from the towns and villages of upland Anatolia, bringing with them a fervent religious expectation. In their dusty robes they moved about the camp, their eyes alight with excitement. They recited relevant verses from the Koran and the Hadith and told tales of martyrdom and prophecy. The men were reminded that they were following in the footsteps of the companions of the Prophet killed at the first Arab siege of Constantinople. Their names were passed from mouth to mouth: Hazret Hafiz, Ebu Seybet ul-Ensari, Hamd ul-Ensari and above all Ayyub, whom the Turks called Eyüp. The holy men reminded their listeners, in hushed tones, that to them fell the honour of fulfilling the word of the Prophet himself:

The Prophet said to his disciples: ‘Have you heard of a city with land on one side and sea on the other two sides?’ They replied: ‘Yes, O Messenger of God.’ He spoke: ‘The last hour [of Judgement] will not dawn before it is taken by 70,000 sons of Isaac. When they reach it, they will not do battle with arms and catapults but with the words “There is no God but Allah, and Allah is great.” Then the first sea wall will collapse, and the second time the second sea wall, and the third time the wall on the land side will collapse, And, rejoicing, they will enter in.’

The words attributed to the Prophet may have been spurious, but the sentiment was real. To the army fell the prospect of completing a messianic cycle of history, a persistent dream of the Islamic peoples since

the birth of Islam itself, and of winning immortal fame. And for those killed in battle blessed martyrdom and the prospect of paradise lay ahead: ‘Gardens watered by running streams, where they shall dwell for ever; spouses of perfect chastity: and grace from God.’