Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453 (43 page)

Read Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453 Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

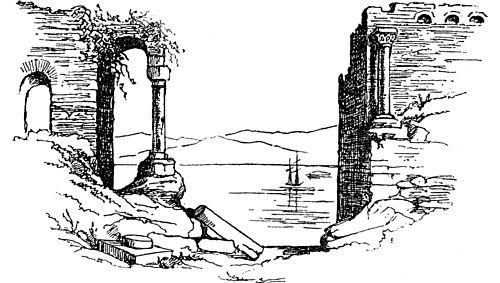

The ruined palace of Hormisdas on the Marmara shore

15 A Handful of Dust

1

‘Tell me please …’, Sherrard, p. 102

2

‘ordered his trumpeters …’, Doukas,

Fragmenta

, p. 296

3

‘attacked them …’, Kritovoulos,

Critobuli,

p. 71

4

‘to create universal terror …’, ibid., p. 71

5

‘everyone they found…’, Barbaro,

Giornale

, p. 55

6

‘threw bricks and …’, Nestor-Iskander, p. 89

7

‘The whole city was filled …’, Melville Jones, p. 51

8

‘their wives and children … friends and wives’, Doukas,

Fragmenta

, p. 295

9

‘beautifully embellished …’, Doukas, trans. Magoulias, p. 228

10

‘slaughter their aged …’, Khoja Sa’d-ud-din, p. 29

11

‘nations, customs and languages’, Melville Jones, p. 123

12

‘plundering, destroying …’, Kritovoulos,

Critobuli,

p. 71

13

‘terrible and pitiful … their bed chambers’, ibid., pp. 71–2

14

‘Slaughtered mercilessly … and the infirm’, Leonard, p. 66

15

‘The newborn babies …’, Doukas,

Fragmenta,

p. 295

16

‘dragging them out …’, Kritovoulos,

Critobuli,

p. 72

17

‘young and modest …’, ibid., p 72

18

‘holy artifacts and …’, ibid.,, p. 73

19

‘walls of churches …’, ibid., p. 73

20

‘The consecrated images …’, Melville Jones, p. 38

21

‘led to the fleet …’, Barbaro,

Diary,

p. 67

22

‘hauled out of the … things were done’, Kritovoulos,

Critobuli

, p. 73

23

‘and from the West …’, Doukas,

Fragmenta,

p. 292

24

‘to search for gold …’, Pertusi,

La Caduta

, vol. 1, p. 34

25

‘and so they put …’, Barbaro,

Diary,

p. 67

26

‘churches, old vaults …’, Kritovoulos,

Critobuli

, p. 74

27

‘men, women, monks …’, Doukas,

Fragmenta,

p. 296

28

‘the fury of… help them’, Pertusi,

La Caduta

, vol. 1, pp. 185–6

29

‘not without great danger …’, ibid., p. 44

30

‘I always knew that …’, ibid., p. 44

31

‘We were in a terrible situation …’, Pertusi,

La Caduta

, vol. 1, p. 36

32

‘all of us would..’, ibid., p. 37

33

‘at midday with …’, Barbaro,

Giornale

, p. 58

34

‘like melons along a canal’, Pertusi,

La Caduta

, vol. 1, p. 36

35

‘some of whom had been drowned …’, ibid., p. 36

36

‘to the very heavens’, Procopius, quoted Freely, p. 28

37

‘suspended from heaven …’, quoted Norwich, vol. 1, p. 203

38

‘trapped as in a net’, Kritovoulos,

Critobuli,

p. 74

39

‘like sheep’, Doukas, trans. Magoulias, p. 225

40

‘a certain spot, and … extraordinary spectacle’, Doukas, trans. Magoulias, p. 227

41

‘in an instant …’, Doukas,

Fragmenta

, p. 292

42

‘ransacked and desolate’, ibid., p. 227

43

‘the blind-hearted emperor’, Khoja Sa’d-ud-din, p. 30

44

‘A desperate battle ensued …’, Tursun Beg, p. 37

45

‘the Emperor turned to …’, Pertusi,

La Caduta

, vol. 1, p. 214

46

‘The Emperor of Constantinople …’, ibid., pp. 184–5

47

‘Weep Christians …’, Legrand, p. 74

48

‘The ruler of Istanbul …’, quoted Lewis,

The Muslim Discovery of

Europe,

p. 30

49

’ seventy of eighty thousand …’, quoted Freely, pp. 211–12

50

‘like a fire or a whirlwind …’, Kritovoulos,

Critobuli,

pp. 74–5

51

‘mounting as (Jesus) … castle of Afrasiyab’, quoted Lewis,

Istanbul

, p. 8

52

‘dumbfounded by … a few pence’, Pertusi,

La Caduta

, vol. 1, pp. 219–21

53

‘gold and silver …’, ibid., p. 327

54

‘women and children …’, Norwich, vol. 3, p. 143

1453–1683

Whichever way I look, I see trouble.

Angelo Lomellino, Podesta of Galata, to his brother, 23 June 1453

The reckoning followed hard on the heels of the fall. The next day, there was a distribution of the booty: according to custom, Mehmet as commander was entitled to a fifth of everything that had been taken. His share of the enslaved Greeks he settled in the city in an area by the Horn, the Phanar district, which would continue as a traditional Greek quarter down to modern times. The vast majority of the ordinary citizens – about 30,000 – were marched off to the slave markets of Edirne, Bursa and Ankara. We know the fates of a few of these deportees because they were important people who were subsequently ransomed back into freedom. Among these was Matthew Camariotes, whose father and brother were killed, and whose family was dispersed; painstakingly he set about finding them. ‘I ransomed my sister from one place, my mother from somewhere else; then my brother’s son: most pleasing to God, I obtained their release.’ Overall, though, it was a bitter experience. Beyond the death and disappearance of loved ones, most shattering to Camariotes was the discovery that ‘of my brother’s four sons, in the disaster three – alas! – through the fragility of youth, renounced their Christian faith … maybe this wouldn’t have happened, had my father and brother survived … so I live, if you can call it living, in pain and grief’. Conversion was a not

uncommon occurrence, so traumatic had been the failure of prayers and relics to prevent the capture of the God-protected city by Islam. Many more captives simply disappeared into the gene pool of the Ottoman Empire – ‘scattered across the whole world like dust’, in the lament of the Armenian poet, Abraham of Ankara.

The surviving notables in the city suffered more immediate fates. Mehmet retained all the significant personages whom he could find, including the Grand Duke Lucas Notaras and his family. The Venetians, whom Mehmet identified as his key opponents in the Mediterranean basin, came in for especially harsh treatment. Minotto, the bailey of their colony, who had played a spirited part in the defence of the city, was executed, together with his son and other Venetian notables; a further twenty-nine were ransomed back to Italy. The Catalan consul and some of his leading men were also executed, whilst a vain hunt was conducted for the unionist churchmen, Leonard of Chios and Isidore of Kiev, who managed to escape unrecognized. A search in Galata for the two surviving Bocchiardi brothers was similarly unsuccessful; they hid and survived.

The Podesta of Galata, Angelo Lomellino, acted promptly to try to save the Genoese colony. Its complicity in the defence of Constantinople made it immediately vulnerable to retribution. Lomellino wrote to his brother that the sultan ‘said that we did all we could for the safety of Constantinople … and certainly he spoke the truth. We were in the greatest danger, we had to do what he wanted to avoid his fury.’ Mehmet ordered the immediate destruction of the town’s walls and ditch, with the exception of the sea wall, destruction of its defensive towers and the handing over of the cannon and all other weapons. The podesta’s nephew was taken off into the service of the palace as a hostage, in common with a number of sons of the Byzantine nobility – a policy that would both ensure good behaviour and provide educated young recruits for the imperial administration.

It was in this context that the fate of the Grand Duke Lucas Notaras was decided. The highest-ranking Byzantine noble, Notaras was a controversial figure during the siege, given a consistently bad press by the Italians. He was apparently against union; his oft repeated remark, ‘rather the sultan’s turban than the cardinal’s hat’, was held up by Italian writers as proof of the intransigence of Orthodox Greeks. It appears that Mehmet was initially minded to make Notaras prefect of the city – an indication of the deeper direction of the sultan’s plans for

Constantinople – but was probably persuaded by his ministers to reverse the decision. According to the ever-vivid Doukas, Mehmet, ‘full of wine and in a drunken stupor’, demanded that Notaras should hand over his son to satisfy the sultan’s lust. When Notaras refused, Mehmet sent the executioner to the family. After killing all the males, ‘the executioner picked up the heads and returned to the banquet, presenting them to the bloodthirsty beast’. It is perhaps more likely that Notaras was unwilling to see his children taken as hostages and Mehmet decided that it was too risky to let the leading Byzantine nobility survive.

The work of converting St Sophia into a mosque began almost at once. A wooden minaret was rapidly constructed for the call to prayer and the figurative mosaics whitewashed over, with the exception of the four guardian angels under the dome, which Mehmet, with a regard for the spirits of the place, preserved. (Other powerful ‘pagan’ talismans of the ancient city also survived for a while intact – the equestrian statue of Justinian, the serpent column from Delphi and the Egyptian column; Mehmet was nothing if not superstitious.) On 2 June, Friday prayers were heard for the first time in what was now the Aya Sofya mosque ‘and the Islamic invocation was read in the name of Sultan Mehmet Khan Gazi’. According to the Ottoman chroniclers, ‘the sweet five-times-repeated chant of the Muslim faith was heard in the city’ and in a moment of piety Mehmet coined a new name for the city:

Islambol

– a pun on its Turkish name, meaning ‘full of Islam’ – that somehow failed to strike an echo in Turkish ears. Miraculously Sheikh Akshemsettin also rapidly ‘rediscovered’ the tomb of Ayyub, the Prophet’s standard-bearer who had died at the first Arab siege in 669 and whose death had been such a powerful motivator in the holy war for the city.

Despite these tokens of Muslim piety, the sultan’s rebuilding of the city was to prove highly controversial to conventional Islam. Mehmet had been deeply disturbed by the devastation inflicted on Constantinople: ‘What a city we have committed to plunder and destruction,’ he is reported to have said when he first toured the city, and when he rode back to Edirne on 21 June he undoubtedly left behind a melancholy ruin, devoid of people. Reconstructing an imperial capital was to be a major preoccupation of his reign – but his model would not be an Islamic one.