Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453 (47 page)

Read Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453 Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

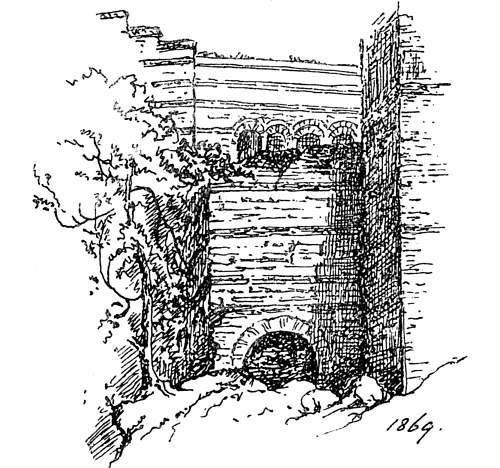

Some of the sea walls of the city, particularly those along the Horn, are mere fragments now, but the great land wall of Theodosius, the third side of the triangle, that confronts the modern visitor arriving

from the airport, seems to ride the landscape as confidently as ever. Up close, it shows its fifteen hundred years: sections are battered and crumbling, downright seedy in some places or incongruously restored in others; towers lean at strange angles, split by earthquakes or cannon balls or time; the fosse that caused the Ottoman troops so much trouble is now peacefully occupied by vegetables; the defences have been breached in places by arterial roads and undermined by a new metro system more effectively than the Serbian miners ever did, but despite the pressures of the modern world, the Theodosian wall is almost continuous for its whole length. One can walk it from sea to sea, following the lie of the land down the sloping central section of the Lycus valley where the walls have been ruined by medieval cannon fire, or stand on the ramparts and imagine Ottoman tents and pennants fluttering on the plain below, ‘like a border of tulips’, and galleys sliding noiselessly on the glittering Marmara or the Horn. Almost all the gateways of the siege have survived; the ominous shadow of their weighty arches retains the power to awe, though the Golden Gate itself, approached down an avenue of cannon balls from Orban’s great guns, was long ago bricked up by Mehmet against the prophetic return of Constantine. For the Turks, the most significant is the Edirne Gate, the Byzantine Gate of Charisius, where Mehmet’s formal entry into Istanbul is recorded by a plaque, but the most poignant of all the gateways that figured in the story of the siege stands completely forgotten a little further up towards the Horn.

Here the wall takes its sudden right-angle turn, and hidden nearby behind a patch of wasteland and directly abutting the shell of the Constantine’s Palace, there is an unremarkable bricked-in arch, typical of the patchwork of alterations and repairs over the centuries. This is said by some to be the prophetic Circus Gate, the small postern left open in the final attack that first allowed Ottoman soldiers onto the walls. Or it might be somewhere else. Facts about the great siege shade easily into myths.

There is one other powerful protagonist of the spring of 1453 still to be discovered within the modern city – the cannon themselves. They lie scattered across Istanbul, snoozing beside walls and in museum courtyards – primitive hooped tubes largely unaffected by five hundred years of weather – sometimes accompanied by the perfectly spherical granite or marble balls that they fired. Of Orban’s supergun

there is now no trace – it was probably melted down in the Ottoman gun foundry at Tophane, followed sometime later by the giant equestrian statue of Justinian. Mehmet took the statue down on the advice of his astrologers, but it appears to have lain in the square for a long time before being finally hauled off to the smelting house. The French scholar Pierre Gilles saw some portions of it there in the sixteenth century. ‘Among the fragments were the leg of Justinian, which exceeded my height, and his nose, which was over nine inches long. I dared not publicly measure the horse’s legs as they lay on the ground but privately measured one of the hoofs and found it to be nine inches in height.’ It was a last glimpse of the great emperor – and of the outsized grandeur of Byzantium – before the furnace consumed them.

The blocked-up arch of the Circus Gate

Epilogue: Resting Places

1

‘It was fortunate for . . .’, quoted Babinger, p. 408

2

‘a short, thick neck . . .’, quoted ibid., p. 424

3

‘men who have seen him . . .’, quoted ibid., p. 424

4

‘his father was domineering . . .’, quoted ibid., p. 411

5

‘There are no ties . . .’, quoted ibid., p. 405

6

‘The great eagle is dead’, quoted Babinger, p. 408

7

‘I am George Sphrantzes . . .’, Sphrantzes, trans. Philippides, p. 21

8

‘my beautiful daughter Thamar …’, ibid., p. 75

9

‘I confess with certainty …’, ibid., p. 91

10

‘either from his wound …’, Pertusi,

La Caduta

, vol. 1, p. 162

11

‘Here lies Giovanni Giustiniani …’, quoted Setton, p. 429

12

‘like a border of tulips’, Chelebi,

Le Siège,

p. 2

13

‘Among the fragments …’, Gilles, p. 130

1

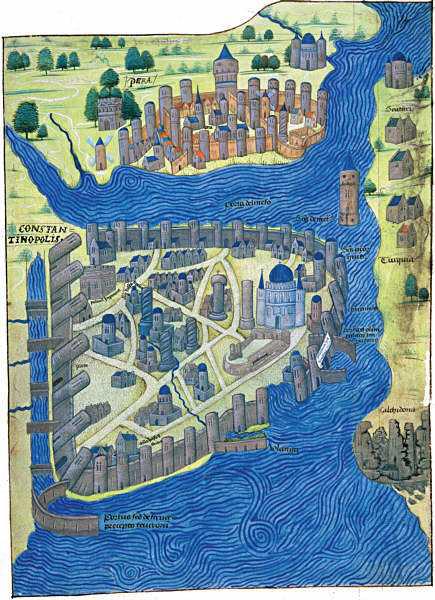

A late-fifteenth-century map of the triangular city, showing St Sophia and the ruined hippodrome on the right, with the main roads leading from the land walls on the left. The Imperial Palace is in the tip of the triangle top left. Above the Golden Horn is the Genoese town of Pera or Galata. Anatolia, marked Turquia, is beyond the straits on the far right.

2

Mehmet the aesthete and scholar: a semi-stylised Ottoman miniature of the sultan in his later years

3

‘We knew not whether we were in heaven or on earth’: the great nave of St Sophia, the most miraculous building of late antiquity

4

A nineteenth-century photograph of the Imperial Palace of Blachernae, Constantine’s headquarters during the siege, which is set into the single-layered land wall near the Golden Horn

5

A section of the triple land wall showing first the line of inner towers, then the lower outer towers shattered by cannon fire. In the centre is the moat, now largely filled in but once bricklined and ten feet deep, that cost the Ottomans so much trouble during the siege. Having crossed it, would-be attackers had to rush the open terrace under heavy fire before they could tackle the outer wall.

6

The great chain with its massive eighteen-inch links that was stretched across the Golden Horn. This nineteenth-century photograph shows that substantial lengths of it were still lying around in the city four hundred years after the siege.

7

Orban’s great siege gun has long since disappeared but several slightly smaller cannon still survive in Istanbul. This massive bronze piece is fourteen feet long, weighs fifteen tons and fired a five-hundred-pound stone ball.

8

A contemporary drawing by Bellini of a Janissary in his distinctive white headdress with arrow quiver, bow and sword. Mehmet is said to have been fascinated but also superstitiously frightened by the Italian master’s ability to conjure apparently living, three-dimensional figures out of the flat paper in defiance of Islamic law.