Coronation Everest (15 page)

Read Coronation Everest Online

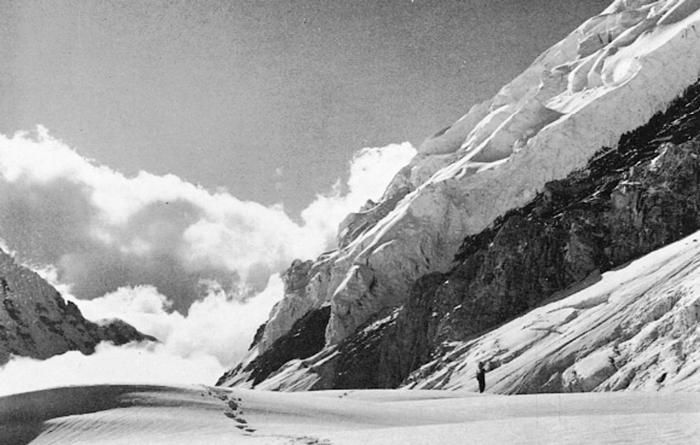

Authors: Jan Morris

What a day it was for great news! That old secluded valley of the Cwm was crisp and sparkling, like a girl decked out in a party frock. The sky was a miraculous blue, the floor of the Cwm dazzlingly white. The massive wall of Nuptse, bounding the Cwm on its southern side, shone mysteriously like silk or rubbed velvet, with the curious greasy sheen of melting snow. From the ridge of Lhotse, directly above us, a small spiral of snow eddied and swirled into the sky, like a genie released from a bottle. There was little wind, and we sat there becalmed in the stillness and the sunshine. The Cwm was silent, as always; but sometimes we heard a sudden high-pitched whistle, thrilling and menacing, as a boulder screamed down from the heights above.

*

The hours dragged by. Endlessly we discussed the chances of success. Hillary and Tenzing had been seen at nine o’clock the day before crossing the South Summit and going strongly up the final ridge. With the rest of the morning before them, they had plenty of time to reach the top and return; but who knew what that last ridge was like? It showed in some of the aerial pictures, but not very clearly; perhaps there was some insuperable obstacle along it, an impassable ledge, dangerous cornices; perhaps their oxygen had failed them, in the last 500 feet; perhaps, faced with the horrors of the altitude, their will had faltered or their bodies slumped. We sat in the dome tent and talked about it.

‘Just coming down to Camp VI,’ said the watchers outside. ‘Somebody’s sitting down, can’t make out who. Anyone care to lay the odds?’

They were clearer now, those little figures on the mountainside. At least they were all safe, I thought. No need for my catastrophe codes, nor my prepared obituaries. Once they were down in the Cwm there was only the passage of the icefall to worry about; and exhausted though the climbers were, I thought they would probably survive that. Not a broken limb had the party suffered; only colds, stomach upsets, and a few minor cases of frost-bite.

Inside the tent there was a mess of newspapers:

The Times

, the

Auckland Weekly News

, with an enormous picture of a lady in a picture hat, a big bouquet pinned to her bosom, presenting prizes, presiding at a banquet, marrying her daughter off, being introduced to a duchess, or performing some such immemorial social duty. I remembered Roberts’s description of his first arrival in New Zealand, when the woman in black behind the hotel reception desk raised her thin eyebrows at his open shirt, and pursed her tight lips primly when he asked the way to the bar. It seemed a strange and bourgeois society for heroes to come from, and I found it difficult to equate the lady in her blue crepe with her countrymen up there on the heights, swaggering, big and breezy.

*

‘Well, yes,’ (I heard a snatch of conversation through the open door of the tent). ‘I suppose so, but the moon will never be quite the same. Who cares about the moon? There are no

little

moons to start with. Nobody goes exploring moons at week-ends, like we go climbing mountains. Anyway, you can keep the moon so far as I’m concerned. All I’m interested in is creature comforts. A l-o-n-g glass of beer! A really good steak! Or a good fug at the Climbers’ Club Hut at Helyg!’

Hastily I turned and crumpled the pages of my newspaper. Somebody had been doing

The Times

crossword puzzle, with a muffled stub of red crayon.

26

Foot – foot – foot – foot – slogging over –

(

Kipling

) (

6

).

The red crayon had answered

that

one in bold and confident letters, so bold that it had gone through the paper, and I could see where the crossword puzzler, on some cold and lonely evening in a flapping tent, had folded the newspaper to give himself something solid to write on. Who had it been, I wondered? Westmacott, during his icefall vigil? Noyce, in some high camp on the Lhotse Face? Hunt, breaking himself away for a moment from the perpetual preoccupations of leadership?

Here was a dispatch of mine. ‘Plans For Double Assault On Peak Of Everest.’ Somewhere between the mountain and the printed page the wrong dateline had crept into it. I had sent the message from Camp III, but it was headed ‘Base Camp, Everest.’ ‘This is a bleak spot high above the Khumbu Glacier,’ I was alleged to have written of our little Base Camp

on

the Khumbu Glacier, ‘with the ugly mass of the icefall spilling below.’ Oh well, probably nobody noticed; to most newspaper readers, Base Camp, Everest was practically the South Summit. ‘Oh my goodness me,’ they would say to me in America, ‘all those weeks on the glacier! Didn’t you feel giddy?’

*

There was a kind of feverish hush over the camp now, and John Hunt sat outside his tent on a packing-case, his waterproof hat jammed on his head, as tense as a violin string. I could see the little figures no longer. They had left the Lhotse Face, and were hidden behind a ridge at the top end of the

Cwm. They must be going well, to get there so soon. Would they move so swiftly if they were suffering the pangs of defeat? On the other hand,

could

they move so swiftly if they had reached the summit of Everest? I remembered the terrible exhaustion of the old Everest climbers, and wondered if a man could go so well after a night at 27,800 feet.

There was a clatter of crampons outside, and Tom Stobart stumped off up the valley with his camera to meet the summit party. I watched him labouring away along the snow, a lonely but determined figure, until he vanished over a ridge. All was then empty in the Cwm around us. The face of Lhotse was blank and lifeless, and all we could see stretching away to its foot was the rolling empty snow. Somewhere hidden away there, not so very far from us, were Hillary, Tenzing and their support party. It was one o’clock, but nobody felt like lunch.

In the corner of the tent there was a radio receiver, tilting drunkenly on the edge of a cardboard box. As the minutes lurched past it murmured intermittent music, and then a cultured Indian voice announced that this was All-India Radio, and that here was the news. We pricked up our ears. Sure enough, very soon Everest was mentioned. Agency messages had now confirmed, said the radio, that the British assault on Everest had failed, and that the expedition was withdrawing from the mountain. There go my competitors, I thought, as active as ever. A slight communal guffaw ran around the tent. Somebody twiddled the knob, half amused, half irritated, and:

‘There they are!’

*

I rushed to the door of the tent, and there emerging from a little gully, not more than five hundred yards away, were four worn figures in windproof clothing. As a man we

leapt out of the camp and up the slope, our boots sinking and skidding in the soft snow, Hunt wearing big dark snow-goggles, Gregory with the bobble on the top of his cap jiggling as he ran, Bourdillon with braces outside his shirt, Evans with the rim of his hat turned up in front like an American stevedore’s. Wildly we ran and slithered up the snow, and the Sherpas, emerging excitedly from their tents, ran after us.

I could not see the returning climbers very clearly, for the exertion of running had steamed up my goggles, so that I looked ahead through a thick mist. But I watched them approaching dimly, with never a sign of success or failure, like drugged men. Down they tramped, mechanically, and up we raced, trembling with expectation. Soon I could not see a thing for the steam, so I pushed the goggles up from my eyes; and just as I recovered from the sudden dazzle of the snow I caught sight of George Lowe, leading the party down the hill. He was raising his arm and waving as he walked! It was thumbs up! Everest was climbed! Hillary brandished his ice-axe in weary triumph; Tenzing slipped suddenly sideways, recovered and shot us a brilliant white smile; and they were among us, back from the summit, with men pumping their hands and embracing them, laughing, smiling, crying, taking photographs, laughing again, crying again, till the noise and the delight of it all rang down the Cwm and set the Sherpas, following us up the hill, laughing in anticipation.

Down we went again, Hillary and Tenzing still roped together, Tom Bourdillon rolling back with his hands in his pockets, grinning, Gregory, fired by the occasion, already sharp and vigorous again. Above the camp most of the Sherpas were waiting in an excited smiling group.

As the greatest of their little race approached them they stepped out, one by one, to congratulate him. Tenzing received them like a modest prince. Some bent their bodies forward, their hands clasped as if in prayer. Some shook hands lightly and delicately, the fingers scarcely touching. One old veteran, his black twisted pig-tail flowing behind him, bowed gravely to touch Tenzing’s hand with his forehead; just as Sonam, down in the valley, had touched the likeness of that saintly Abbot.

We moved into the big dome tent, and sat around the summit party, throwing questions at them, still laughing, unable to believe the truth. Everest was climbed, and these two mortal men in front of us, sitting on old boxes, had stood upon its summit, the highest place on earth! And nobody knew but us! The day was still dazzlingly bright – the snow so white, the sky so blue; and the air was still so vibrant with excitement; and the news, however much we expected it, was still somehow such a wonderful surprise – shock waves of that moment must still linger there in the Western Cwm, so potent were they, and so gloriously charged with pleasure. Now and then the flushed face of a Sherpa appeared in the doorway, with a word of delight; and as we lay there on boxes, rolls of bedding and sleeping-bags, Hillary and Tenzing ate a leathery omelette apiece, and told us their story. I can hear Hillary’s voice today, and see the lump of omelette protruding inside his left cheek, as he paused for a moment from mastication to describe the summit of Mount Everest.

The whole world knows the story now: how the two of them had spent a terrible night in the tiny tent of Camp IX, crookedly pitched on an uncomfortable ridge, one half of the floor higher than the other; how they had

struggled and talked and dreamed the night away, eating sardines; how early on the morning of May 29 they had crept out of the tent, to find the day fine and clear, so that Thyangboche monastery could be seen there, ten miles away and 19,000 feet below, and the little lake, tucked away below Pumori, that Sonam and I had visited two months before; how they had laboured along the last ridge, and hauled themselves up a brutal chimney, and expected each successive bump to be the summit; until at last, at 11.30 in the morning, they had found themselves truly at the top, with the flags they carried fluttering in the breeze.

Hillary had planted John’s crucifix, as he had promised, and Tenzing had placed some small offerings on the ground, to propitiate the divinities supposed to live upon that Himalayan Olympus. They had embraced each other, and taken photographs, and eaten some mint cake; and after fifteen minutes on the summit, they had turned and begun the downward climb.

‘What did it feel like when we got there? Well I’ll tell you, though I don’t know if Tenzing agrees; when we found it really was the summit at last I heaved a sigh of relief, and that’s a fact. No more steps to cut! No more ridges to traverse! It was a great relief to me, I can tell you. D’you agree, Tenzing?’

And Tenzing, his hat pushed back on his head, his face permanently wreathed and crinkled with smiles, laughed and nodded and ate his omelette, while the worshipping Sherpas at the door gazed at him like apostates before the Pope. Indeed, he was a fine sight, sitting there in his moment of triumph, before the jackals of fame closed in upon him.

‘Yes, but there must have been more than mere relief in your mind,’ I said to him, ‘after all these years of Everest

climbing. What else did you feel when you stood upon the summit?’

This time Tenzing paused in his eating and thought hard about his reply. ‘Very excited,’ he said judicially, ‘not too tired, very pleased.’

Half past two on the afternoon of May 30. I scribbled it all down in a tattered old notebook, drinking in the flavour of the occasion, basking in the aura of incredulous delight that now flooded through our little camp. The talk was endless and vivacious, and would no doubt continue throughout that long summer afternoon and into the night; but there were only three full days to the Coronation, and as I scribbled I realized that I must start down the mountain again that very afternoon, to get a message off to Namche the next morning. This time there would be no night’s rest at Camp III. I must go straight down the icefall to Base Camp that evening. My body, still aching from the upward climb in the morning, did not like the sound of this at all; but at the back of my slightly befuddled brain a small voice told me that there could be no argument. Wilfrid Noyce had always planned to make this last dash down the mountain-side for me; but now I was here myself, and need not bother him.

‘I’ll come with you James!’ said Michael Westmacott instantly, when I told them my plans; and remembering the newly oozing ice-bog of the route, I accepted his offer gratefully. We loaded our rucksacks, fastened our crampons, shook hands all round, and set off down the slope. ‘Good luck!’ a voice called from the dome tent; I turned around to

wave my thanks, and stood for a moment (till the rope tugged me on) looking at the blank face of Lhotse, just falling into shadow, and the little clump of happy tents that was Camp IV. Christmas angels were in the Cwm that day.

So we strode off together down the valley. In a downhill climb the most experienced man should travel last; but I was so obviously in a condition of impending disintegration, and the way was so sticky and unpleasant from the thaw, that Westmacott went first, and I followed. At the head of the Cwm, though we did not know it, Wilfrid Noyce, Charles Wylie and some Sherpas were making their way down to Camp IV from the Lhotse Face, where they had been packing up the tents to bring them lower. As they crossed a small ridge they caught sight of our two small figures, far below, all alone in the Cwm and travelling hard towards Camp III. Perhaps there were ghosts about, Noyce thought as he watched our dour silent progress; the angel theory did not occur to him.

For me it was a wet and floundering march. So soft, receptive and greedy was the snow that at almost every step I sank deeply into it, often up to my thighs, and had then to extricate myself with infinite trouble, with that confounded rope (connecting me with Westmacott) rapidly getting tauter as I struggled, until suddenly there would be a great sharp pull upon it, and Mike would turn round to see what was happening, and find me sprawling and flapping in the snow, like some tiresome sea-creature on the sand. I remember vividly the labour and the discomfort of it all, with the wet seeping into my boots, and the shaft of my ice-axe sinking into the snow, my head heavy and my brain muzzy but excited. As we travelled down the Cwm, so the sun went down, and the valley was plunged into shadow, chilling and unfriendly.

Here and there were our footsteps of the morning’s journey, barely recognizable now, but squashy and distorted, as if Snowmen had passed that way. Long and deep were the crevasses that evening, and as we crossed them their cool interiors seemed almost inviting in their placidity. The shadows chased us down the valley, and soon I could no longer watch my own image on the snow, elongated like a dream figure, with my old hat swollen on my head and my ice-axe, like a friar’s stave, swinging in my hand. Before long we were peering ahead through the dusk, still struggling and slipping, but still moving steadily down the mountain.

Camp III again, in the half-light. We stopped for lemonade and sweets, and I looked about me with a sudden pang of regret at the melting plateau, the sagging tents, the tottering wireless aerial, the odd boxes and packing-cases. I would never set foot on this place again: this was my goodbye to the mountain. So befuddled was I by the altitude and

the exertion, so feverish of emotion, that a hot tear came to my eye as I sat there shivering in the cold, my boots soggy and my head throbbing, looking about me at the loathsome decaying wilderness of ice that surrounded us.

Down we plunged into the icefall, and I realized again what an odious place it had become. The bigness and messiness and cruelty of it all weighed heavily upon me, a most depressing sensation. Any grandeur the icefall possessed had gone, and squalidness had overcome it. Now more than ever it was a moving thing;

seracs

were disintegrating, plateaus splitting, ice-towers visibly melting; and there were creaking, groaning and cracking noises.

The ice was here, the ice was there,

The ice was all around;

It cracked and growled, and roared and howled,

Like noises in a swound!

Through this pile of white muck we sped, and as we travelled I wondered (in a hazy sort of way) what we would find at the bottom. How many Izzards or Jacksons had encamped at Base Camp in my absence, setting up their transmitters, poised to fall upon the descending Sherpas? Was there any conceivable way in which the news of the ascent could have reached the glacier already? Nobody had preceded us down the mountain, but what about telepathy, mystic links, smoke signals, choughs, spiders, swounds? What if I arrived at camp to find that my news was already on its way to London and some eager Fleet Street office? I shuddered at the thought, and taking a moment off to hitch up my rucksack, nearly fell headlong into a crevasse.

‘Stay where you are,’ said Westmacott a little sharply. ‘And belay me if you can!’

One of his pole bridges, across a yawning chasm, had been loosened by the thaw, and looked horribly unsafe. I thrust my ice-axe into the snow and put the rope around it while Westmacott gently edged himself across. I could just see him there in the gloom, precariously balanced. One pole was lashed to another, and he had to move them around, or tie them again, or turn them over, or hitch them up, or do something or other to ensure that we were not precipitated into the depths, as Peacock once remarked, in the smallest possible fraction of the infinite divisibility of time. This, after a few anxious and shivery moments, he did: and I followed him cautiously across the void.

Who would have thought, when Hunt accepted me over that admirable lunch at the Garrick Club, that my assignment would end like this, scrambling dizzily and feverishly down the icefall of Everest in the growing darkness? Who could have supposed that I would ever find myself in quite so historically romantic a situation, dashing down the flanks of the greatest of mountains to deliver a message for the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II? It was all perfectly –

oops, steady, nasty slippery bit

! – all perfectly ridiculous. It must all be some midnight dream, by brandy out of Gruyère; or a wild boyhood speculation, projected by some intricate mechanism of the time-space theory. Slithering down the mountain with the news from Everest! What poppycock!

‘Do try and wake up,’ said Westmacott. ‘It would be a help if you’d belay me sometimes!’

I murmured my apologies, blushing in the dark. Indeed by now, as we passed the tents of Camp II, I was a pitiful messenger. All the pieces of equipment fastened to my person seemed to be coming undone. The ice-axe constantly slipped from my fingers and had to be picked up. The rope

threatened to unloose itself. The laces of my boots trailed. The fastening of one of my crampons had broken, so that the thing was half on, half off my foot, and kept tripping me up. I had torn my windproof jacket on an ice-spur, and a big flap of its red material kept blowing about me in the wind. My rucksack, heavy with kit, had slipped on its harness, so that it now bumped uncomfortably about in the small of my back. (I have had similar sensations since, in less atrocious degree; for example at airports when, standing there helpless beside the gate, passport in one hand, luggage tickets in the other, mackintosh over one arm, hold-all over the right, a camera around my neck, a book under my arm, a typewriter between my knees, a ticket between my teeth – when, standing there in this cluttered condition, I have been asked by some unspeakable official for my inoculation certificate.)

Still we went on, my footsteps growing slower and wearier and more fumbling, and even Westmacott rather tired by now. Presently we made out the black murk that was the valley of the Khumbu; and shortly afterwards we lost our way. Everything had changed so in the thaw. Nothing was familiar. The little red route flags were useless. There was no sign of a track. We stood baffled for a few moments, faced with an empty, desert-like snow plateau, almost at the foot of the icefall. Then: ‘Come on,’ said Westmacott boldly, ‘we’ll try this way! We’ll glissade down this slope here!’

He launched himself upon the slope, skidding down with a slithery crunching noise. I followed him at once, and, unable to avoid a hard ice-block at the bottom, stubbed my toe so violently that my big toe-nail came off. The agony of it! It was like something in an old Hollywood comedy, with indignity piled upon indignity, and

the poor comic hero all but obliterated by misfortune!

But I had little time to brood upon it, for Westmacott was away again already, and the rope was pulling at me. As we neared the bottom of the icefall, the nature of the ground became even more distasteful. The little glacier rivulets which had run through this section had become swift-flowing torrents. Sometimes we balanced our shaky way along the edge of them; sometimes we jumped across; sometimes, willy-nilly, we waded through the chill water, which eddied into our boots and made them squelch as we walked.

At last, at the beginning of the glacier moraine, I thought I would go no farther. It was pitch black by now, and Westmacott was no more than a suggestion in front of me. I sat down on a boulder, panting and distraught, and disregarded the sudden sharp pull of the rope (like totally ignoring a bite on a deep-sea fishing line).

‘What’s the matter?’

‘I think I’m going to stop here for a bit,’ (as casually as I could manage it) ‘and get my breath back. I’ll just sit here quietly for a minute or two. You go on, Mike, don’t bother about me.’

There was a slight pause at the other end of the rope.

‘Don’t be so ridiculous,’ said Westmacott: and so definitive was this pronouncement that I heaved myself to my feet again and followed him down the glacier. Indeed, we were almost there. The ground was familiar again, and above us loomed the neighbourly silhouette of Pumori. The icefall was a jumbled dream behind us. I felt in the pocket of my windproof to make sure my notes were there, with the little typed code I was going to use. All was safe.

Presently there was a bobbing light in front of us; and out of the gloom appeared an elderly Sherpa with a lantern,

grinning at us through the darkness. He helped us off with our crampons and took the ice-axe from my hand, which was unaccountably shaking with the exertion.

‘Anybody arrived at Base Camp?’ I asked him quickly, thinking of those transmitters. ‘Is Mr. Jackson here again, or Mr. Tiwari?’

‘Nobody, sahib,’ he replied. ‘There’s nobody here but us Sherpas. How are things on the mountain, sahib? Is all well up there?’

All well, I told him, shaking his good old hand. All very well.

*

So we plunged into our tents. There were some letters, and some newspapers, and a hot meal soon appeared. Mike came to join me in eating it, and we squeezed into my tent comfortably, and ate and read there in the warm. I was exhausted, for the climb from III to IV and thence down to base was no easy day’s excursion for a beginner; and it seemed to me that the icefall, in its present debased and degenerate condition, had been nothing short of nightmarish.

‘Was it really as bad as all that?’ I asked. ‘Or was it just me?’

‘It was bad!’ Westmacott replied shortly, peering at me benevolently over his spectacles, like a scholarly physician prescribing some good old-fashioned potion.

We lay and lazed there for a time, and chatted about it, and remembered now and then that Everest had been climbed, and wondered how the news would be received in London. I made a few tentative conjectures about honours lists. ‘Sir Edmund Hillary’ certainly sounded odd. What about Tenzing? ‘Sir Tenzing and Lady Norkay’? ‘Lord Norkay of Chomolungma’? But no, he was Indian,

or Nepalese (nobody quite knew which) and could qualify for no such resplendent titles: he would be honoured royally anyway. We heaved a few sleepy sighs of satisfaction, and presently Westmacott eased himself gradually out of the tent. I thanked him for all his kindness on the icefall, and we said good night.