Coronation Everest (17 page)

Read Coronation Everest Online

Authors: Jan Morris

As we descended a strange and uncomfortable lassitude overcame me, the effect perhaps of de-acclimitization. I had been weak on the glacier high above; now I was not only weak, but intolerably lazy. I could hardly bring myself to move my limbs, or urge my lungs to operate; and often, as we made our way along the stream, I would take off my pack and sit down upon a rock, burying my head in my arms, trying to recover my resolution. It was too ridiculous. The path was easy, the country delightful; the monsoon was about to burst, and there was a smell of

fresh moisture in the air; but there, it had been a long three months on Everest, and a long, long march from Lobuje, and my body and spirit were rebelling.

It was evening now. The air was cool and scented. Pine trees were all about us again, and lush foliage, and the roar of the swollen river rang in our ears. On the west bank of the Dudh Khosi, about six miles south of Namche Bazar, there was a Sherpa hamlet called Benkar. There, as the dusk settled about us, we halted for the night. In a small square clearing among the houses Sonam set up my tent, and I erected the aerial of my radio receiver. The Sherpas, in their usual way, marched boldly into the houses round about and established themselves among the straw, fires and potatoes of the upstairs rooms. Soon there was a smell of roasting and the fragrance of tea. As I sat outside my tent meditating, with only a few urchins standing impassively in front of me, Sonam emerged with a huge plate of scrawny chicken, a mug of

chang

, tea, chocolate and

chuppatis

.

How far had my news gone, I wondered as I ate? Was it already winging its way to England from Katmandu; or was it still plodding over the Himalayan foothills in the hands of those determined runners? Would tomorrow, June 2, be both Coronation and Everest Day? Or would the ascent fall upon London later, like a last splendid chime of the Abbey bells? There was no way of knowing; I was alone in a void; the chicken was tough; the urchins unnerving; I went to bed.

*

But the morning broke fair. Lazily, as the sunshine crept up my sleeping-bag, I reached a hand out of my mummied wrappings towards the knob of the wireless. A moment of fumbling; a few crackles and hisses; and then the voice of an Englishman.

Everest had been climbed, he said. Queen Elizabeth had been given the news on the eve of her Coronation. The crowds waiting in the wet London streets had cheered and danced to hear of it. After thirty years of endeavour, spanning a generation, the top of the earth had been reached and one of the greatest of all adventures accomplished. This news of Coronation Everest (said that good man in London) had been first announced in a copyright dispatch in

The Times

.

I jumped out of my bed, spilling the bed-clothes about me, tearing open the tent-flap, leaping into the open in my filthy shirt, my broken boots, my torn trousers; my face was thickly bearded, my skin cracked with sun and cold, my voice hoarse. But I shouted to my Sherpas, whose bleary eyes were appearing from the neighbouring windows:

‘Chomolungma finished! Everest done with! Okay!’

‘Okay, sahib!’ the Sherpas shouted back. ‘Breakfast now?’

*

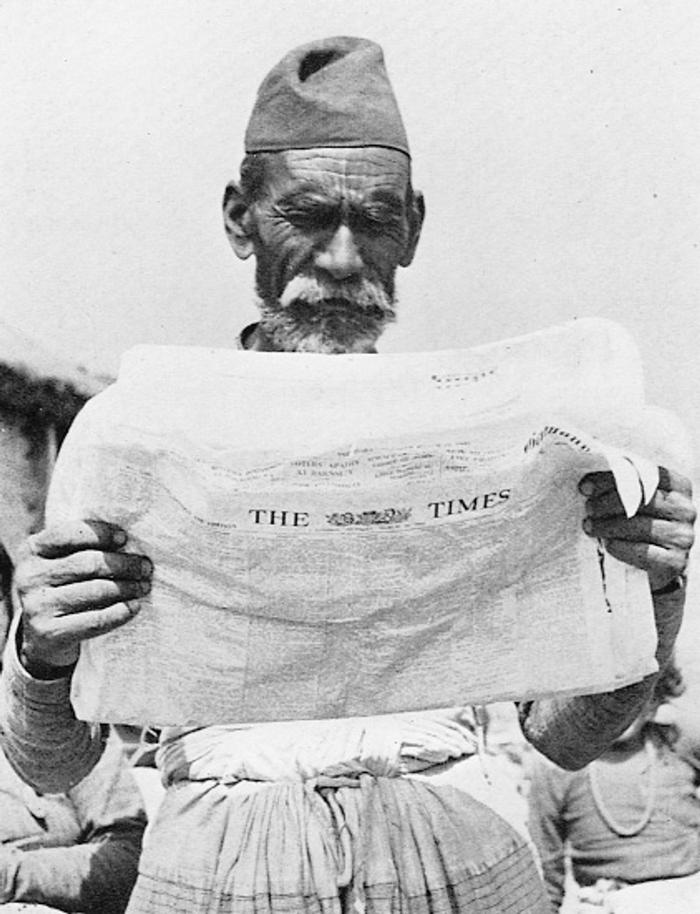

Far away in Westminster Abbey, as the notables prepared themselves, Field-Marshal Montgomery opened his newspaper that morning to read the news from Everest: so an adventure ended, crossed the continents, and joined the footnotes of history.

Half a century later, the memory of that happy triumph is tinged with regret. The very idea of Mount Everest has lost some of its magic, as our world has shrunk, humanity has multiplied itself and almost nowhere is unfamiliar. Men have walked on the Moon since 1953, and literally hundreds of men and women have stood on the very spot, 29,002 feet above sea level, where Hillary and Tenzing wrote their names in the history books fifty years ago.

Many of them have gone there as clients of commercial climbing outfits, paying large sums of money for the experience, and this has demeaned the reputation of Everest as a place of spiritual meaning. So has the litter they have left behind them. So has the new ease of access to the mountain, by aircraft and motor-road, and by the proliferation of lodges and hotels along the trekking routes. So has the plethora of books, magazine articles, memoirs, films and videos, some magnificent, some wretched, which has made more worldly the once transcendental image of Chomolungma.

The notion of a Queen of England’s coronation has lost its arcane fascination, too. Not just in England, but around the world, the British royal family has come to feel more like mere fodder for the tabloids than material for

historical allegory. Loyalties have become fragmented. Mysticism is banished from the affairs of State. Thousands will no doubt still stand agog, if ever another English monarch is crowned at Westminster Abbey, but not with the same mysterious depth of pride and latent superstition that animated them in 1953.

I always stood outside these sources of inspiration anyway – Everest never felt holy to me, still less kings or queens – so that my own regrets, when I look back at the old adventure, are much more personal. So many of my companions on the mountain, who became my friends, have died since then, some on other hills, some on the plains below – Tenzing among the first, John Hunt (by then Lord Hunt of Llanfair Waterdine, Knight of the Garter) just too soon to celebrate the Golden Jubilee of his success. Away in the Himalayas not too many Sherpas are still around to share their recollections of the expedition over the

chang

. At home in Wales, when I have seen survivors of the climb gathered for their periodical reunions at the foot of Snowdon, they have seemed to me no more than so many elderly civilized gentlemen, leaner and fitter than most, but contemplating like everyone else the sad effects of time.

But if Everesters age and die, if Everest itself is tarnished rather, if Coronations are out of mode and news can be flashed instantaneously by satellite anywhere on earth – still that first ascent of 1953 remains, to my mind, one of the most honourable and innocent of the great adventures. It has not been diminished by the passing years. Mount Everest is littered now with the corpses of mountaineers of many nationalities, but not one of them lost their lives in 1953. None of the climbers vulgarly exploited their celebrity in the aftermath of success, and some of them

have devoted their later years to the welfare of the Sherpa people. I thought them very

decent

men when I first met them, and essentially decent they remained.

The 1953 British Mount Everest Expedition did not often betray its own values, which may sometimes seem old-fashioned values nowadays, but are none the weaker for that. In an age full of tawdry shame and disillusion, it remains a memory to be proud of.

TREFAN MORYS

, 2003

- Fisher, Lord,

1