Crime at Christmas (13 page)

Read Crime at Christmas Online

Authors: Jack Adrian (ed)

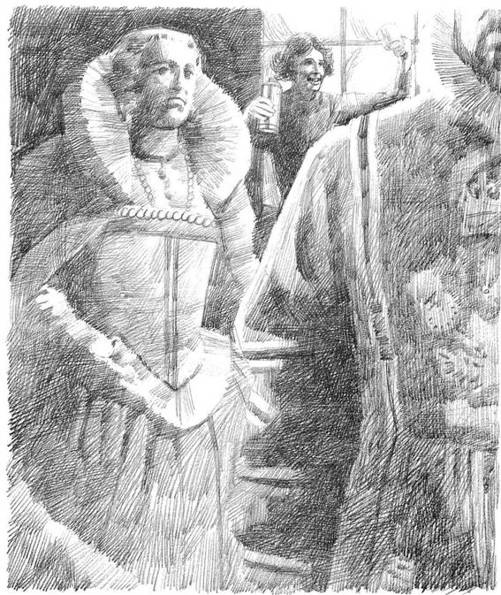

'Twenty-one,

twenty-two. . .Wolsey. Queen Elizabeth, Guy Fawkes, Napoleon ought to go on a

diet. Ever heard of eighteen days, Nap? Poor old Julius Caesar looks as though

he'd been sun-bathing on the Lido. He's about due for the melting-pot.'

In her eyes

they were a second-rate set of dummies. The local theory that they could

terrorise a human being to death or madness seemed a fantastic notion.

'No,'

concluded Sonia. 'There's really more in Poke's bright idea.'

Again she

saw the sun-smitten office—for the big unshielded window faced south—with its

blistered paint, faded wall-paper, ink-stained desks, typewriters, telephones,

and a huge fire in the untidy grate. Young Wells smoked his big pipe, while the

subeditor—a ginger, pig-headed young man—laid down the law about the mystery

deaths.

And then

she heard Poke's toneless dead-man's voice.

'You may be

right about the spiritualist. He died of fright—but not of the waxworks. My

belief is that he established contact with the spirit of his dead friend, the

alderman, and so learned his real fate.'

'What

fate?' snapped the sub-editor.

'I believe

that the alderman was murdered,' replied Poke.

He clung to

his point like a limpet in the face of all counter-arguments.

'The

alderman had enemies,' he said. 'Nothing would be easier than for one of them

to lie in wait for him. In the present circumstances,

I

could commit a murder in the

Waxworks, and get away with it.'

'How?'

demanded young Wells.

'How? To

begin with, the Gallery is a one-man show and the porter's a bonehead. Anyone

could enter, and leave, the Gallery without his being wise to it.'

'And the

murder?' plugged young Wells.

With a

shudder Sonia remembered how Poke had glanced at his long knotted fingers.

'If I could

not achieve my object by fright, which is the foolproof way,' he replied, 'I

should try a little artistic strangulation.'

'And leave

your marks?'

'Not

necessarily. Every expert knows that there are methods which show no trace.'

Sonia

fumbled in her bag for the cigarettes which were not there.

'Why did I

let myself think of that, just now?' she thought. 'Really too stupid.'

As she

reproached herself for her morbidity, she broke off to stare at the door which

led to the Hall of Horrors.

When she

had last looked at it, she could have sworn that it was tightly closed. . . But

now it gaped open by an inch.

She looked

at the black cavity, recognizing the first test of her nerves. Later on, there

would be others. She realized the fact that, within her cool, practical self,

she carried a hysterical, neurotic passenger, who would doubtless give her a

lot of trouble through officious suggestions and uncomfortable reminders.

She

resolved to give her second self a taste of her quality, and so quell her at

the start.

'That door

was merely closed,' she remarked as, with a firm step, she crossed to the Hall

of Horrors and shut the door.

One

o'clock. I begin to realize that there is more in this than I thought. Perhaps

I'm missing my sleep. But I'm keyed up and horribly expectant. Of what? I don't

know. But I seem to be waiting for—something. I find myself listening—listening.

The place is full of mysterious noises. I know they're my fancy. . .And things

appear to move. I can distinguish footsteps and whispers, as though those

waxworks which I cannot see in the darkness are beginning to stir to life.

Sonia

dropped her pencil at the sound of a low chuckle. It seemed to come from the

end of the Gallery which was blacked out by shadows.

As her

imagination galloped away with her, she reproached herself sharply.

'Steady,

don't be a fool. There must be a cloak-room here. That chuckle is the air

escaping in a pipe—or something. I'm betrayed by my own ignorance of

hydraulics.'

In spite of

her brave words, she returned rather quickly to her corner.

With her

back against the wall she felt less apprehensive. But she recognized her cowardice

as an ominous sign.

She was

desperately afraid of someone—or something—creeping up behind her and touching

her.

'I've

struck the bad patch,' she told herself. 'It will be worse at three o'clock

and work up to a climax. But when I make my entry, at three, I shall have

reached the peak. After that every minute will be bringing the dawn nearer.'

But of one

fact she was ignorant. There would be no recorded impression at three o'clock.

Happily

unconscious, she began to think of her copy. When she returned to the

office—sunken-eyed, and looking like nothing on earth—she would then rejoice

over every symptom of groundless fear.

'It's a

story all right,' she gloated, looking at Hamlet. His gnarled, pallid features

and dark smouldering eyes were strangely familiar to her.

Suddenly

she realized that he reminded her of Hubert Poke.

Against her

will, her thoughts again turned to him. She told herself that he was exactly

like a waxwork. His yellow face—symptomatic of heart-trouble—had the same

cheesy hue, and his eyes were like dull black glass. He wore a denture which

was too large for him, and which forced his lips apart in a mirthless grin.

He always

seemed to smile—even over the episode of the lift—which had been no joke.

It happened

two days before. Sonia had rushed into the office in a state of molten

excitement because she had extracted an interview from a Personage who had just

received the Freedom of the City. This distinguished freeman had the

reputation of shunning newspaper publicity, and Poke had tried his luck, only

to be sent away with a flea in his ear.

At the back

of her mind, Sonia knew that she had not fought level, for she was conscious of

the effect of violet-blue eyes and a dimple upon a reserved but very human

gentleman. But in her elation she had been rather blatant about her score.

She

transcribed her notes, rattling away at her typewriter in a tremendous hurry,

because she had a dinner-engagement. In the same breathless speed she had

rushed towards the automatic lift.

She was

just about to step into it when young Wells had leaped the length of the

passage and dragged her back.

'Look,

where you're going,' he shouted.

Sonia

looked—and saw only the well of the shaft. The lift was not waiting in its

accustomed place.

'Out of

order,' explained Wells before he turned to blast Hubert Poke, who stood by.

'You

almighty chump, why didn't you grab Miss Fraser, instead of standing by like a

stuck pig?'

At the time

Sonia had vaguely remarked how Poke had stammered and sweated, and she accepted

the fact that he had been petrified by shock and had lost his head.

For the

first time, she realized that his inaction had been deliberate. She remembered

the flame of terrible excitement in his eyes and his stretched ghastly grin.

'He

hates

me,' she thought. 'It's my fault.

I've been

tactless and cocksure.'

Then a

flood of horror swept over her.

'But he

wanted to see me crash. It's almost

murder.'

As she

began to tremble, the jumpy passenger she carried reminded her of Poke's

remark about the alderman.

'He had

enemies.'

Sonia shook

away the suggestion angrily.

'My

memory's uncanny,' she thought. 'I'm stimulated and all strung up. It must be

the atmosphere. . . Perhaps there's some gas in the air that accounts for these

brainstorms. It's hopeless to be so utterly unscientific. Poke would have

made a better job of this.'

She was

back again to Hubert Poke. He had become an obsession.

Her head

began to throb and a tiny gong started to beat in her temples. This time, she

recognized the signs without any mental ferment.

'Atmospherics.

A storm's coming up. It might make things rather thrilling. I must concentrate

on my story. Really, my luck's in.'

She sat for

some time, forcing herself to think of pleasant subjects—of arguments with

young Wells and the Tennis Tournament. But there was always a point when her

thoughts gave a twist and led her back to Poke.

Presently

she grew cramped and got up to pace the illuminated aisle in front of the

window. She tried again to talk to the waxworks, but, this time, it was not a

success.

They seemed

to have grown remote and secretive, as though they were removed to another

plane, where they possessed a hidden life.

Suddenly

she gave a faint scream. Someone—or something—had crept up behind her, for she

felt the touch of cold fingers upon her arm.

Two

o'clock. They're only wax. They shall not frighten me. But they're trying to.

One by one they're coming to life. . .Charles the Second no longer looks sour

dough. He is beginning to leer at me. His eyes remind me of Hubert Poke.

Sonia

stopped writing, to glance uneasily at the image of the Stuart monarch. His

black velveteen suit appeared to have a richer pile. The swart curls which fell

over his lace collar looked less like horse-hair. There really seemed a gleam

of amorous interest lurking at the back of his glass optics.

Absurdly,

Sonia spoke to him, in order to reassure herself.

'

Did

you

touch me? At the first hint of a

liberty, Charles Stuart, I'll smack your face. You'll learn a modern journalist

has not the manners of an orange-girl.'

Instantly

the satyr reverted to a dummy in a moth-eaten historical costume.

Sonia

stood, listening for young Wells' footsteps. But she could not hear them,

although the street now was perfectly still. She tried to picture him, propping

up the opposite building, solid and immovable as the Rock of Gibraltar.

But it was

no good. Doubts began to obtrude.

'I don't

believe he's there. After all, why should he stay? He only pretended, just to

give me confidence. He's gone.'

She shrank

back to her corner, drawing her tennis-coat closer, for warmth. It was growing

colder, causing her to think of tempting things—of a hot-water bottle and a

steaming tea-pot.

Presently

she realized that she was growing drowsy. Her lids felt as though weighted with

lead, so that it required an effort to keep them open.

This was a

complication which she had not foreseen. Although she longed to drop off to

sleep, she sternly resisted the temptation.

'No. It's

not fair. I've set myself the job of recording a night spent in the Waxworks.

It

must

be the genuine thing.'

She blinked

more vigorously, staring across to where Byron drooped like a sooty flamingo.

'Mercy, how

he yearns! He reminds me of . . . No, I won't think of

him .

. .I must keep awake. . .Bed. .

.blankets, pillows. . . No.'

Her head

fell forward, and for a minute she dozed. In that space of time, she had a

vivid dream.

She thought

that she was still in her corner in the Gallery, watching the dead alderman as

he paced to and fro, before the window. She had never seen him, so he conformed

to her own idea of an alderman—stout, pompous, and wearing the dark-blue,

fur-trimmed robe of his office.

'He's got a

face like a sleepy pear,' she decided. 'Nice old thing, but brainless.'

And then,

suddenly, her tolerant derision turned to acute apprehension on his account, as

she saw that he was being followed. A shape was stalking him as a cat stalks a

bird.

Sonia tried

to warn him of his peril, but, after the fashion of nightmares, she found

herself voiceless. Even as she struggled to scream, a grotesquely long arm shot

out and monstrous fingers gripped the alderman's throat.

In the same

moment, she saw the face of the killer. It was Hubert Poke.

She awoke

with a start, glad to find that it was but a dream. As she looked around her

with dazed eyes, she saw a faint flicker of light. The mutter of very faint

thunder, together with a patter of rain, told her that the storm had broken.

It was

still a long way off, for Oldhampton seemed to be having merely a reflection

and an echo.

'It'll

clear the air.' thought Sonia.

Then her

heart gave a violent leap. One of the waxworks had come to life. She distinctly

saw it move, before it disappeared into the darkness at the end of the

Gallery.

She kept

her head, realizing that it was time to give up.

'My nerve's

crashed,' she thought. 'That figure was only my fancy. I'm just like the

others. Defeated by wax.'

Instinctively,

she paid the figures her homage. It was the cumulative effect of their grim

company, with their simulated life and sinister associations, that had rushed

her defences.

Although it

was bitter to fail, she comforted herself with the reminder that she had

enough copy for her article. She could even make capital out of her own

capitulation to the force of suggestion.

With a

slight grimace, she picked up her note-book. There would be no more on-the-spot

impressions. But young Wells, if he was still there, would be grateful for the

end of his vigil, whatever the state of mind of the porter.

She groped

in the darkness for her signal-lamp. But her fingers only scraped bare polished

boards.

The torch

had disappeared.

In a panic,

she dropped down on her knees, and searched for yards around the spot where she

was positive it had lain.

It was the

instinct of self-preservation which caused her to give up her vain search.

'I'm in

danger,' she thought. 'And I've no one to help me now. I must see this through

myself.'

She pushed

back her hair from a brow which had grown damp.

'There's a

brain working against mine. When I was asleep, someone—or something—stole my

torch.'