Crime at Christmas (19 page)

Read Crime at Christmas Online

Authors: Jack Adrian (ed)

It was nine

o'clock on Christmas morning, and Angela Willett had just finished her packing.

Outside the

skies were dark and cheerless, snow and rain were falling together, so that

this tiny furnished room had almost a palatial atmosphere in comparison with

the drear world outside.

'I suppose

it's too early to cook the sausages—by the way, our train leaves at ten

tonight, so we needn't invent ways of spending the evening—come in.'

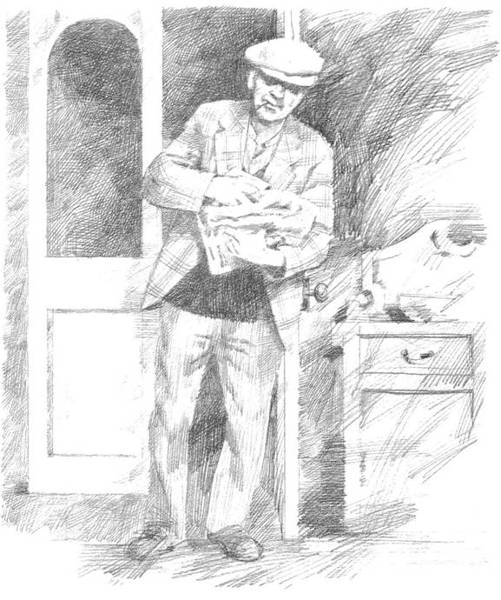

It was Joe

the Runner, rather wet but smiling. He carried under his arm something wrapped

in an old newspaper.

'Excuse me,

miss,' he said, as he removed the covering, 'but a gent I met in the street

asked me to give you this.'

'A turkey!'

gasped Angela. 'How wonderful. . .who was it?'

'I don't

know, miss—an old gentleman,' said Joe vaguely. 'He said "Be sure an' give

it to the young lady herself—wishin' her a happy Christmas".'

They gazed

on the carcase in awe and ecstasy. As the front door slammed, announcing Joe's

hasty departure:

'An old

gentleman,' said Angela slowly. 'Uncle Peter!'

'Uncle

grandmother!' smiled John. 'I believe he stole it!'

'How

uncharitable you are!' she reproached him. 'It's the sort of thing Uncle Peter

would do. He always had that Haroun al Raschid complex—I wrote and told him we

were leaving for Canada tonight. I'm sure it was he.'

Half-convinced,

John Willett prodded at the bird. It seemed a little tough.

'Anyway,

it's turkey,' he said, 'And, darling, I adore turkey stuffed with chestnuts. I

wonder if there are any shops open

There was a

large cavity at one end of the bird, and as he lifted the turkey up by the

neck, the better to examine it, something dropped to the table with a flop. It

was a tight roll of paper. He shook the bird again and a second fell from its

unoffending body.

'Good God!'

gasped John.

With

trembling hands he cut the string that bound the roll

'It's

money!' she whispered.

John

nodded.

'Hundred

dollar bills. . .five hundred of them at least!' he said hollowly.

Their eyes

met.

'Uncle

Peter!' she breathed. 'The darling!'

Mr Peter

Elmer, the eminent ship owner, received the following day a telegram which was

entirely meaningless:

Thank you a

thousand times for your thought and generosity. You have given us a wonderful

start and we shall be worthy of your splendid kindness.

It was

signed 'Angela'. Mr Peter Elmer scratched his head.

And at that

moment Inspector Mailing was interrogating Harry the Valet in the little police

station at Carfane.

'Now come

across, Harry,' he said kindly. 'We know you got the money out of the safe.

Where did you plant it? You couldn't have taken it far, because the butler saw

you leaving the room. Just tell us where the money is, and I'll make it all

right for you when you come up in front of the old man.'

'I don't

know what you're talking about,' said Harry the Valet, game to the last.

-

No Room at the Inn

by

BILL PRONZINI

B

ILL PRONZINI

(b. 1943) is a writer to his fingertips,

a pro of the first water. This does not mean to say he particularly enjoys

writing; he doesn't. Particularly. Show me the writer who leaps out of bed

every morning, bright-eyed and bushy tailed, just raring to tackle that ol'

typewriter, and I'll show you a nitwit. Writing's fine when the burn is on and

every word's a gem, every paragraph seems fresh-minted, but otherwise what

we're talking is mostly hard graft, and since the late 1960s Bill Pronzini has

certainly done his share of that.

Thus far,

he must have had a hand in well over eighty books, over half of which have been

detective stories or novels of suspense, either under his own name or one or

two pseudonyms, either solo or in collaboration (Pronzini is known as one of

the most

simpatico

collabs in the business). He's

edited (again, alone or with others) quantities of anthologies in the mystery,

horror, SF and Western genres, often rescuing fine old-time writers from an

oblivion they didn't deserve. He's written maybe 180 short stories, maybe more

(and there are some real twist-ending stunners amongst them). He even did a

stint producing torrid paperbacks for the sex market, but that was long ago and

far away, and in any case his sense of the absurd kept getting in the way of

the action.

Bill's main

series detective has no name. This was not deliberate. He just didn't bother to

fix a handle on his PI narrator in the first couple of books and then (for

probably the only time in his career) couldn't figure out a way of dropping a

name into the narrative without it appearing crass. So nameless he was and

'Nameless' he's become.

'Nameless'

is terribly real. He's gruff, he's intelligent, he gets depressed, he has a

mordant sense of humour, he panics about his health, he does stupid things and

he does smart things; he has his highs and his lows. I do sometimes think that

a capricious Fate slaps the poor so-and-so around just a little too much, but

otherwise 'Nameless' seems to me to be one of the most flesh-and-blood

fictional characters around.

But what I

really admire are Pronzini's novels of suspense—such as

Games

(1977),

Night Screams

(1979, with Barry Malzberg),

Masques

(1981) and

The Lighthouse

(1987, with Marcia Muller)—which

are just that: chilling exercises in pure wired-up tension. The kind of books

where you're gritting your teeth so hard over the last fifty-odd pages that

'The End' brings little immediate relief, especially as he usually has some

savage and unforeseen (but always fairly, if subliminally,

signalled)

twist all ready and waiting for you, the final sucker-punch that leaves you

twitching. Sheer class.

Bill also

writes a nifty Western. Secretly, he's hooked on oaters and has been since

devouring copies of

Dime Western, Thrilling Western, Texas Rangers, .44 Western

and a slew of other titles as a

kid. So to tempt him to do an original story for this anthology, it seemed

wisest to hit him where he's weakest.

A Western?

In

Crime At

Christmas

? Ah,

but its hero, John Quincannon, is a fully-fledged, no-nonsense

detective

—who has already appeared,

incidentally, in

Quincannon

(1985) and the ingeniously-plotted

Beyond The Grave

(1986, with Marcia Muller). And it all happens on a wild night in

the Sierra Nevada—the night of 24 December 1894. . .

W

HEN the

snowstorm started, Quincannon was high up in a sparsely populated section of

the Sierra Nevada—alone except for his rented horse, with not much idea of

where he was and no idea at all of where Slick Henry Garber was.

And as if

all of that wasn't enough, it was almost nightfall on Christmas Eve.

The storm

had caught him by surprise. The winter sky had been clear when he'd set out

from Big Creek in mid-morning, and it had stayed clear until two hours ago;

then the clouds had commenced piling up rapidly, the way they sometimes did in

this high-mountain country, getting thicker and darker-veined until the whole

sky was the colour of moiling coal smoke. The wind had sharpened to an icy

breath that buffeted both him and the ewe-necked strawberry roan. And now, at

dusk, the snow flurries had begun—thick Hakes driven and agitated by the wind

so that the pine and spruce forests through which the trail climbed were a

misty blur and he could see no more than forty or fifty feet ahead.

He rode

huddled inside his fleece-lined long coat and rabbit-fur mittens and cap,

feeling sorry for himself and at the same time cursing himself for a

rattlepate. If he had paid more mind to that build-up of clouds, he would have

realized the need to find shelter much sooner than he had. As it was, he had

begun looking too late. So far no cabin or mine-shaft or cave or suitable gegraphical

configuration had presented itself—not one place in all this vast wooded

emptiness where he and the roan could escape the snapping teeth of the storm.

A man had

no sense wandering around an unfamiliar mountain wilderness on the night before

Christmas, even if he

was

a manhunter by trade and a greedy glory-hound by inclination. He ought to be

home in front of a blazing fire, roasting chestnuts in the company of a good

woman. Sabina, for instance. Dear, sweet Sabina, waiting for him back in San

Francisco. Not by his hearth or in his bed, curse the luck, but at least in the

Market Street offices of Carpenter and Quincannon, Professional Detective

Services.

Well, it

was his own fault that he was alone up here, freezing to death in a snowstorm.

In the first place he could have refused the job of tracking down Slick Henry

Garber when it was offered to him by the West Coast Banking Association two

weeks ago. In the second place he could have decided not to come to Big Creek

to investigate a report that Slick Henry and his satchel full of counterfeit

mining stock were in the vicinity. And in the third place he could have

remained in Big Creek this morning when Slick Henry managed to elude his

clutches and flee even higher into these blasted mountains.

But no,

Rattlepate John Quincannon had done none of those sensible things. Instead he

had accepted the Banking Association's fat fee, thinking only of that

and

of the additional $5000 reward for

Slick Henry's apprehension or demise being offered by a mining coalition in

Colorado

and

of the glory of nabbing the most

notorious—and the most dangerous—confidence trickster operating west of the

Rockies in this year of 1894. Then, after tracing his quarry to Big Creek, he

had not only bungled the arrest but made a second mistake in setting out on

Slick Henry's trail with the sublime confidence of an unrepentant sinner

looking for the Promised Land—only to lose that trail two hours ago, at a road

fork, just before he made his

third

mistake of the day by underestimating the weather.

Christmas,

he thought. 'Tis the season to be jolly. Bah. Humbug.

Ice

particles now clung to his beard, his eyebrows; kept trying to freeze his

eyelids shut. He had continually to rub his eyes clear in order to see where he

was going. Which, now, in full darkness, was along the rim of a snow-skinned

meadow that had opened up on his left. The wind was even fiercer here, without

a single tree to deflect its force. Quincannon shivered and huddled and cursed,

and felt sorrier for himself by the minute.

He should

never have decided to join forces with Sabina and open a detective agency. She

had been happy with her position as a female operative with the Pinkerton

Agency's Denver office; he had been more or less content working in the San

Francisco office of the United States Secret Service. What had possessed him to

suggest, not long after their first professional meeting, that they pool their

talents? Well, he knew the answer to that well enough.

Sabina

had possessed him. Dear, sweet, un-seducible,

infuriating Sabina. . .

Was that

light ahead?

He scrubbed

at his eyes and leaned forward in the saddle, squinting. Yes, light—lamplight.

He had just come around a jog in the trail, away from the open meadow, and

there it was, ahead on his right: a faint glowing rectangle in the night's

churning white-and-black. He could just make out the shapes of buildings, too,

in what appeared to be a clearing before a sheer rock face.

The

lamplight and the buildings changed Quincannon's bleak remonstrations into

murmurs of thanksgiving. He urged the stiff-legged and balky roan into a

quicker pace. The buildings took on shape and definition as he approached.

There were three of them, grouped in a loose triangle; two appeared to be

cabins, fashioned of rough-hewn logs and planks, each with a sloping roof,

while the bulkiest structure had the look of a barn. The larger cabin, the one

with the lighted window, was set between the other two and farther back near

the base of the rock wall.

A lane led

off the trail to the buildings. Quincannon couldn't see it under its covering

of snow, but he knew it was there by a painted board sign nailed to one of the

trees at the intersection.

TRAVELLER'S REST,

the sign said, and below that, in

smaller letters,

Meals and Lodging.

One of the tiny roadhouses, then, that dotted the Sierras and

catered to prospectors, hunters, and foolish wilderness wayfarers such as himself.

It was

possible, he thought as he turned past the sign, that Slick Henry Garber had

come this way and likewise been drawn to the Traveller's Rest. Which would

allow Quincannon to make amends today, after all, for his earlier bungling, and

perhaps even permit him to spend Christmas Day in the relative comfort of the

Big Creek Hotel. Given his recent run of foul luck, however, such a

serendipitous turnabout was as likely to happen as Sabina presenting him, on

his return to San Francisco, with the holiday gift he most desired.

Nevertheless,

caution here was indicated. So despite the warmth promised by the lamplit

window, he rode at an off-angle toward the barn. There was also the roan's

welfare to consider. He would have to pay for the animal if it froze to death

while in his charge.

If he was

being observed from within the lighted cabin, it was covertly: no one came out

and no one showed himself in the window. At the barn he dismounted, took

himself and the roan inside, struggled to reshut the doors against the howling

thrust of the wind. Blackness surrounded him, heavy with the smells of animals

and hay and oiled leather. He stripped off both mittens, found a lucifer in one

of his pockets and scraped it alight. The barn lantern hung from a hook near

the doors; he reached up to light the wick. Now he could see that there were

eight stalls, half of which were occupied: three saddle horses and one work

horse, each nibbling a pile of hay. He didn't bother to examine the saddle

horses because he had no idea what type of animal Slick Henry had been riding.

He hadn't got close enough to his quarry all day to get a look at him or his

transportation.

He led the

roan into an empty stall, unsaddled it, left it there munching a hay supper of

its own. Later, he would ask the owner of Traveller's Rest to come out and give

the beast a proper rubdown. With his hands mittened again he braved the storm

on foot, slogging through calf-deep snow to the lighted cabin.

Still no

one came out or appeared at the window. He moved along the front wall, stopped

to peer through the rimed window glass. What he could see of the big parlour

inside was uninhabited. He ploughed ahead to the door.

It was

against his nature to walk unannounced into the home of a stranger, mainly

because it was a fine way to get shot, but in this case he had no choice. He

could have shouted himself hoarse in competition with the storm before anyone

heard him. Thumping on the door would be just as futile; the wind was already doing

that. Again he stripped off his right mitten, opened his coat for easy access

to the Remington Navy revolver he carried at his waist, unlatched the door with

his left hand, and cautiously let the wind push him inside.

The entire

parlour was deserted. He leaned back hard against the door to get it closed

again and then called out, 'Hello the house! Company!' No one answered.

He stood

scraping snowcake off his face, slapping it off his clothing. The room was

warm: a log fire crackled merrily on the hearth, banking somewhat because it

hadn't been fed in a while. Two lamps were lit in here, another in what looked

to be a dining room adjacent. Near the hearth, a cut spruce reached almost to

the raftered ceiling; it was festooned with Christmas decorations—strung

popcorn and bright-coloured beads, stubs of tallow candles in bent can tops,

snippets of fleece from some old garment sprinkled on the branches to resemble

snow, a five-pointed star atop the uppermost branch.

All very cosy

and inviting, but where were the occupants? He called out again, and again

received no response. He cocked his head to listen. Heard only the plaint of

the storm and the snicking of flung snow against the windowpane—no sound at all

within the cabin.

He crossed

the parlour, entered the dining room. The puncheon table was set for two, and

in fact two people had been eating there not so long ago. A clay pot of venison

stew sat in the centre of the table; when he touched it he found it and its contents

still slightly warm. Ladlings of stew and slices of bread were on each of the

two plates.

The hair

began to pull along the nape of his neck, as it always did when he sensed a

wrongness to things. Slick Henry? Or something else? With his hand now

gripping the butt of his Navy, he eased his way through a doorway at the rear

of the dining room.

Kitchen and

larder. Stove still warm, a kettle atop it blackening smokily because all the

water it had contained had boiled away. Quincannon transferred the kettle to

the sink drainboard. Moved then to another closed door that must lead to a

bedroom, the last of the cabin's rooms. He depressed the latch and pushed the

door wide.

Bedroom,

indeed. And as empty as the other three rooms. But there were two odd things

here: the sash of a window in the far wall was raised a few inches; and on the

floor was the base of a lamp that had been dropped or knocked off the bedside

table. Snow coated the window sill and there was a sifting of it on the floor

and on the lamp base.

Quincannon

stood puzzled and scowling in the icy draft. No room at the inn?, he thought

ironically. On the contrary, there was plenty of room at this inn on Christmas

Eve. It didn't seem to have

any

people in it.