Crime at Christmas (22 page)

Read Crime at Christmas Online

Authors: Jack Adrian (ed)

'You're not

coming? I thought you said—‘

'No. I

shall have to stay and see the party through. There's a little matter of family

business I'd better dispose of while I have the chance.'

Hilda

looked at him in slightly amused surprise.

'Well, if

you feel that way,' she said. 'You seem to be very devoted to your family all

of a sudden. You'd better keep an eye on Bessie while you are about it. She's

had about as much as she can carry.'

Hilda was

right. Bessie was decidedly merry. And Timothy continued to keep an eye on her.

Thanks to his attentions, by the end of the evening, when Christmas Day had been

seen in and the guests were fumbling for their wraps, she had reached a stage

when she could barely stand. 'Another glass,' thought Timothy from the depths

of his experience, 'and she'll pass right out.'

'I'll give

you a lift home, Bessie,' said Roger, looking at her with a professional eye.

'We can just squeeze you in.'

'Oh,

nonsense, Roger!' Bessie giggled. 'I can manage perfectly well. As if I

couldn't walk as far as the end of the drive!'

'I'll look

after her,' said Timothy heartily. 'I'm walking myself, and we can guide each

other's wandering footsteps home. Where's your coat, Bessie? Are you sure

you've got all your precious presents?'

He

prolonged his leave-taking until all the rest had gone, then helped Bessie into

her worn fur coat and stepped out of the house, supporting her with an

affectionate right arm. It was all going to be too deliciously simple.

Bessie

lived in the lodge of the old house. She preferred to be independent, and the

arrangement suited everyone, especially since James after one of his reverses

on the turf had brought his family to live with his mother to save expense. It

suited Timothy admirably now. Tenderly he escorted her to the end of the drive,

tenderly he assisted her to insert her latchkey in the door, tenderly he

supported her into the little sitting-room that gave out of the hall.

There

Bessie considerately saved him an enormous amount of trouble and a possibly

unpleasant scene. As he put her down upon the sofa she finally succumbed to the

champagne. Her eyes closed, her mouth opened and she lay like a log where he

had placed her.

Timothy was

genuinely relieved. He was prepared to go to any lengths to rid himself from

the menace of blackmail, but if he could lay his hands on the damning letter

without physical violence he would be well satisfied. It would be open to him

to take it out of Bessie in other ways later on. He looked quickly round the

room. He knew its contents by heart. It had hardly changed at all since the day

when Bessie first furnished her own room when she left school. The same old

battered desk stood in the corner, where from the earliest days she had kept

her treasures. He Hung it open, and a flood of bills, receipts, charitable

appeals and yet more charitable appeals came cascading out. One after another,

he went through the drawers with ever increasing urgency, but still failed to

find what he sought. Finally he came upon a small inner drawer which resisted

his attempts to open it. He tugged at it in vain, and then seized the poker

from the fireplace and burst the flimsy lock by main force. Then he dragged the

drawer from its place and settled himself to examine its contents.

It was

crammed as full as it could hold with papers. At the very top was the programme

of a May Week Ball for his last year at Cambridge. Then there were snapshots,

press-cuttings—an account of his own wedding among them—and, for the rest,

piles of letters, all in his hand-writing. The wretched woman seemed to have

hoarded every scrap he had ever written to her. As he turned them over, some of

the phrases he had used in them floated into this mind, and he began to

apprehend for the first time what the depth of her resentment must have been

when he threw her over.

But where

the devil did she keep the only letter that mattered?

As he

straightened himself from the desk he heard close behind him a hideous, choking

sound. He spun round quickly. Bessie was standing behind him, her face a mask

of horror. Her mouth was wide open in dismay. She drew a long shuddering

breath. In another moment she was going to scream at the top of her voice. . .

Timothy's

pent-up fury could be contained no longer. With all his force he drove his fist

full into that gaping, foolish face. Bessie went down as though she had been

shot and her head struck the leg of a table with the crack of a dry stick

broken in two. She did not move again.

Although it

was quiet enough in the room after that, he never heard his stepmother come in.

Perhaps it was the sound of his own pulses drumming in his ears that had

deafened him. He did not even know how long she had been there. Certainly it

was long enough for her to take in everything that was to be seen there, for

her voice, when she spoke, was perfectly under control.

'You have

killed Bessie,' she said. It was a calm statement of fact rather than an

accusation.

He nodded,

speechless.

'But you

have not found the letter.'

He shook

his head.

'Didn't you

understand what she told you this evening? The letter is in the post. It was

her Christmas present to you. Poor, simple, loving Bessie!'

He stared

at her, aghast.

'It was

only just now that I found that it was missing from my jewel-case,' she went

on, still in the same flat, quiet voice. 'I don't know how she found out about

it, but love—even a crazy love like hers—gives people a strange insight

sometimes.'

He licked

his dry lips.

'Then you

were Leech?' he faltered.

'Of course.

Who else? How otherwise do you think I could have kept the house open and my

children out of debt on my income?

No,

Timothy, don't come any nearer. You are not going to commit two murders

tonight. I don't think you have the nerve in any case, but to be on the safe

side I have brought the little pistol your father gave me when he came out of

the army in 1918. Sit down.'

He found

himself crouching on the sofa, looking helplessly up into her pitiless old

face. The body that had been Bessie lay in between them.

'Bessie's

heart was very weak,' she said reflectively. 'Roger had been worried about it

for some time. If I have a word with him, I daresay he will see his way to

issue a death certificate. It will, of course, be a little expensive. Shall we

say a thousand pounds this year instead of five hundred? You would prefer that,

Timothy, I dare say, to—the alternative?'

Once more

Timothy nodded in silence.

'Very well.

I shall speak to Roger in the morning—after you have returned me Bessie's

Christmas present. I shall require that for future use. You can go now,

Timothy.'

by

MARGERY ALLINGHAM

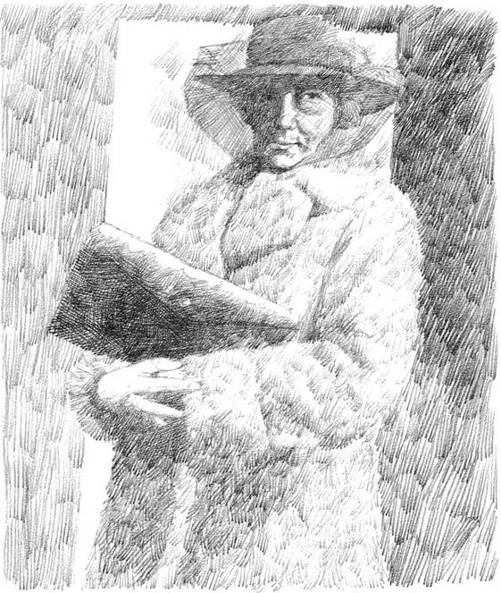

M

ARGERY ALLINGHAM

(1904-66) couldn't help becoming a

writer, although it wasn't so much Fate that pushed her to it as blood (an

ichor later to feature fairly strongly in her work).

Her

grandfather, William Allingham, was owner-editor of the

Christian Globe

back in the 1860s; her great-uncle,

John Allingham, the black sheep of the family, spurned writing tracts for his

brother and became a prolific hack for the bloods and penny-dreadfuls of the

1880s, immersing himself so deeply in the persona of his chief character, Ralph

Rollington, that he later took on his name. Her mother, Emily Allingham

{nee

Hughes), was a journalist who also

wrote weepies and Had-I-But-Knowners, and her father was the great H.J. of his

ilk, something of a legend in his own lifetime who wrote prodigiously for

dozens of boys' weekly papers from the 1890s to the year of his death (1935),

and at one time was earning a princely £2.10.

s.

6

d

. (just over £2.50) per thousand

words, a whole guinea more than the drudges who banged out adult serials for

the newspapers.

Margery

Allingham herself left school at fifteen to work in the Amalgamated Press's

vast fiction factory in London's Farringdon Street (aided and abetted by her

father, then still one of the AP's chief scribblers), had a play,

Dido And Aeneas,

produced at the age of 18 (she once

considered taking to the boards professionally, but wisely thought better of

it), her first book, an energetic smuggling romp

Blakkerchief Dick

, published at 19 (actually written

a couple of years before), and another play,

Water In A Sieve,

at 21.

What ought

to have happened after that was another thirty-odd years hard labour grinding

out saleable trash for the cheaper end of the market. What actually happened

was that she began to write breezy and entertaining detective stories (some

under the absurd pseudonym 'Maxwell March') which gradually, through the 1930s,

became very good and sharply characterized detective novels, and then, during

the 1940s and 1950s, superlative and skilful novels of crime.

She also

wrote masterly short stories. Here is a late offering, in which her very human

sleuth Albert Campion helps the excitable Superintendent Stanislaus Oates

(Allingham was always very inventive with her names) clear his desk as

retirement looms. . .