Crime at Christmas (26 page)

Read Crime at Christmas Online

Authors: Jack Adrian (ed)

'Shall we

say a lucky fool?' suggested Mr Jones.

'Luck,

yes!' snapped Beecham.

'That

shows,' said Mr Jones, 'how little you know me. You must get to know me better.

Call round some time. Second Thursdays, you know. Tea.

And

cakes.'

To give the

grim old man of Scotland Yard his due he almost enjoyed the turkey and plum

pudding and the port that followed.

Despite his

company he would have enjoyed the unusual even entirely had it not been for the

business which found him there. As it was he said little. Nor did he do more

than listen occasionally to the ceaseless flow of light-hearted chatter which poured

from the lips of Mr Jones.

He gave

himself up to a waiting game and tried to calculate the number of miles that

had pounded themselves out under the wheels of the train.

Mr Jones

glanced at his watch.

'Eight

o'clock? The snow's keeping us back. We were due in at Friars Topliss at five

minutes to, surely?'

Beecham

looked up at the mention of Friars Topliss, but still he said nothing. Mr Jones

offered a cigar, which was refused, and then lit one himself.

Ten minutes

later the train began to slow down.

'Now where

are we?' said Mr Jones.

All down

the dining car there was much rubbing of steamed windows, which answered no

questions. An attendant, laden with Christmas fare on a tray passed quickly.

'Tell me,

steward, where are we?' Mr Jones inquired.

'Running

into Etching Vale, sir,' replied the attendant. 'Friars Topliss in twenty-five

minutes.'

'Thank

you,' said Mr Jones, and turned to Maxwell.

'This is

where we get off,' he said. 'Got everything, Maxwell?'

'Everything,

sir,' Maxwell answered.

'Don't

forget the bag.'

Maxwell

stopped and picked up the shabby bag.

'Here it

is, sir.'

Mr Jones

rose. Maxwell rose too. Beecham stared, dissatisfied with he knew not what.

Maxwell

helped Mr Jones into his big overcoat, pulled on his own and waited. Mr Jones

pulled his hat down over his ears and turned up the collar of his coat.

The train

stopped.

'Well,

good-bye, Beecham, dear fellow,' Mr Jones said breezily. 'And, if I don't see

you before, a Happy New Year.'

And out to

the snow-covered platform he went, with Maxwell and the shabby little bag after

him.

Beecham

blinked. That little bag. . .Was it possible? Even before Hadlow Cribb reached

the train? Or, by some trick, while he, Beecham, had been waiting his chance in

the guard's van?

'Crafty,

but I wonder if he's

really

a fool?'

he thought solemnly.

The driving

wind covered Mr Jones and the faithful Maxwell with snow in the twinkling of an

eye. They dashed across the bleak platform of Etching Vale to the shelter of

the station wall. And under this shelter they hurried to the barriers. Here Mr

Jones offered two tickets.

The

collector peered at the tickets in the doubtful lamplight.

'Pardon,

sir,' he said, 'but this is Etching Vale.'

'Remarkable

how you can tell, with all this snow on it,' remarked Mr Jones.

'These

tickets are for Friars Topliss, sir,' said the collector.

'I know,'

said Mr Jones, 'but I've changed my mind. I thought I'd get off here. It sort

of called to me.'

'Not

allowed to break the journey, sir,' the collector reminded him. 'I'm afraid

you'll have to pay again.'

Mr Jones

thrust a note into the collector's hand.

'Take it

out of that,' he said, 'and buy your wife something for Christmas out of the

balance.'

'No wife,

sir,' the collector grinned.

'Soon will

have,' Mr Jones assured him, 'with such charm as yours.'

He passed

out into the snow-covered station square of Little Etching Vale, the soft

footfalls of Maxwell on his left and, as he soon realized, other soft footfalls

on his right. He turned and there once more was the stolid figure of Detective-Inspector

Beecham.

'Not

again!' he exclaimed. 'But, my dear Beecham, I thought you were going on?'

'I thought

you might be, too,' said Beecham.

'I changed

my mind,' Mr Jones informed him.

'I changed

my mind,' retorted Beecham.

'A costly

process, I found it,' said Mr Jones.

'I didn't!'

said Beecham.

'Oh, well,

of course, you're known to the police,' said Mr Jones, 'which makes a

difference!'

He smiled

and waited, but Beecham waited too.

'Where

now?' he asked.

'Where

would you like to go?' said Beecham.

'You don't

mean, do you, that the drinks are now on you?' said Mr Jones. 'But Beecham, my

own, this is too touching! Very well—there's a decent-looking, old fashioned

hostel over there. Shall we?'

'Anywhere,'

growled Beecham.

They

crossed the square to the old-fashioned hostel where, to Mr Jones' surprise,

the Scotland Yard man immediately booked a private room and ordered the drinks

to be sent up there.

'If you'll

join me,' he said to Mr Jones.

'Delighted,'

Mr Jones agreed. 'Does Maxwell remain in the weather and hold the horses'

heads?'

'There'll

be room for the three of us upstairs,' said Beecham.

'What could

be better?' said Mr Jones.

And

upstairs they went, with a waiter and tray to follow them.

'Cosy,'

remarked Mr Jones, when the waiter had left them and closed the door. 'Shall

you be staying here long?'

'About as

long as it will take me to go through that little bag of yours,' Beecham

answered.

'Beecham!'

Mr Jones gasped. 'I don't understand you.'

'You will,'

said Beecham. 'I always thought you'd be too clever. You let me see your train

tickets this afternoon. After that, I just had to take this trip with you. Hand

over the bag.'

'You know,

Beecham, my sweet,' said Mr Jones, 'really I don't think you have the right.'

'I can soon

get that,' said Beecham. 'Please yourself, if you want to waste time. You'll

waste it in my presence, that's all.'

Mr Jones

sighed.

'Maxwell,'

he said, 'nobody trusts us. It's a suspicious world. Pass the little bag to the

gentleman.'

Maxwell

passed the little bag to the gentleman, and the gentleman, frowning, promptly

dragged it open. Out fell pyjamas, combs, and toothbrushes. Nothing else.

Beecham clicked his teeth and looked up.

'Pockets,

probably?' he said.

'No

friendliness at all, observed Mr Jones with a fresh sigh. 'Your pockets,

Maxwell.'

Maxwell

emptied his pockets. Mr Jones emptied his. The detective's complexion darkened.

Pie turned once more to the little bag, fumbled inside it, threw it on the

floor. His hands passed swiftly, but certainly, down the attire of the other

two men; then, with a muttered exclamation, he picked up a telephone that stood

on a corner table.

'Friars

Topliss police, quick!' he shouted.

'You might

tell me, sweet Beecham, Mr Jones put in, 'what

is

on your mind.'

But Beecham

didn't. He sat glaring at the instrument in front of his nose until there was a

faint tinkle.

'Yes?' he

roared. 'This is Detective-Inspector Beecham of Scotland Yard. Is the

six-fourteen from Liverpool Street—what? Good Lord! Battered up? But I saw him—the

jewels? Gone! I'll come along!'

He dropped

the receiver and spun round.

'Without

having the faintest idea as to what is on your mind,' said Mr Jones, 'I think

you must admit that I never batter them up. I may have many failings, but

never

that.'

'I don't

exactly know where you come into this,' snapped Beecham, 'but bear this in

mind. I'll land you.'

'I doubt

it,' Mr Jones smiled. 'You'd like to, I fear, but it's such a disappointing

world.'

Beecham

strode to the door.

'Say

good-bye to the gentleman, Maxwell,' said Mr Jones.

And Maxwell

said good-bye to the gentleman.

'Dapper'

Dawlish, expert but unlikeable, let himself into his Baker Street flat and

snapped on the lights. He was satisfied with himself and the world in general.

Or, at least, he was until he snapped on the lights.

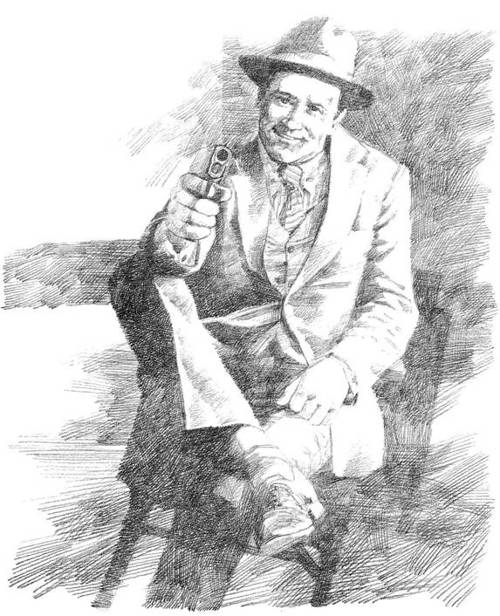

Then he

found himself looking down the barrel of an automatic, and he changed his

opinion of the world at once.

'Good evening,' said Mr Jones. 'Or morning. Or what is it? Travelling

about the world in a snowstorm makes one lose one's sense of time.'

'Who are you?' snarled Dawlish.

'Doesn't matter in the least,' said Mr Jones.

'What do you want?'

'The jewels you stole from Mr Hadlow Cribb on the Friars Topliss train,'

said Mr Jones. 'And I want them now. I've been waiting two hours without a

fire. I'm depressed. And when I'm depressed I'm nasty. That bulge in your right

pocket, I believe. Come on! One—two—’

Which was where 'Dapper' Dawlish threw in.

'I'm hanged if I see how you knew,' he grumbled.

'But, of course, I knew,' said Mr Jones. 'It was I who had you put wise

this afternoon that the stuff would be on the train.'

'You?'

'Mind, you wouldn't have stood an earthly if I hadn't been on the train to

take their attention away,' Mr Jones added. 'They watched dear old Cribb and

you'd never have got near him. Brains, my lad. That's what gets you to the top.

'Mind,

I

couldn't

have got the things. I'm too popular with the C.I.D. They won't let me

out of their sight. Which is why I sometimes have to leave the labouring to

others. Which reminds me.'

He opened the parcel of gems, separated one from the rest, and tossed it

on the table.

'The labourer is worthy of his hire,' he said, with a smile. 'You'd have

got two—or even three—if you hadn't battered him up. Battering-up is a thing I

detest. Or, at least, I've always thought so. I may change my mind one day.

Even this day. Try following me and see! Good-bye, Mr—Dawlish the name is, I

believe. Charmed to have met you. And a Merry Christmas.'