Crime at Christmas (27 page)

Read Crime at Christmas Online

Authors: Jack Adrian (ed)

A Present For

Christmas

by

ROBERT

ARTHUR

W

HY IS

Robert Arthur (real name Robert

Arthur Feeler, 1909-69) so neglected? This is not a rhetorical question. I have

no real idea of the answer. As a writer of short stories from the 1930s to the

1960s he was certainly as imaginative as Frederic Brown; on occasion as caustic

(though by no means as obsessive) as Cornell Woolrich. Brown and Woolrich

posthumously flourish (and rightly so); mention Robert Arthur's name to both

mystery and fantasy enthusiasts and the response is likely to be 'Who?'

Well, very

briefly, here's who. Born in the Phillippines into a typically peripatetic army

family; first job in oil. That lasted seven years, from 1929 to 1936, though

even then he was working at cracking the pulp, later the slick, markets and

playing the field: mysteries, weirds, Westerns, science fiction. Joined MGM as

a writer in 1937; from then on sat behind a typewriter, either as freelance or

editor.

Maybe

that's got something to do with his lack of profile. Arthur did a good many

editing chores in his lifetime and a good many of the editing chores he did

were uncredited. Of the score or more hugely popular anthologies

quote-edited-unquote by Alfred Hitchcock, Arthur did all the hard graft on at

least a third, possibly nearly half—that's to say, he chose the stories, copy-edited

them, dickered with authors and agents, prowled through the proofs; it may well

be that he wrote Alf's Intros as well. For not, I suspect, an awful lot of

money. And for absolutely no kudos.

He veered

off to a certain extent from the mainstream of writing by doing film work, TV

work, and (probably more to his taste) a good deal of radio work, both as

writer and producer. For radio he hammered out scripts for

The Mysterious Traveller

(as well as editing the excellent

spin-off digest magazine) and

Murder By Experts.

Yet he was still a prodigious wordsmith for the pulps even when he

was doing other things and was particularly proficient at producing the

short-sharp-shock story (one, 'Change Of Address', is really one of the neatest

little murderer-exposed-due-to-the-malice-of-Fate tales of the past forty

years).

In the

writing business, reputations still largely rest on books—objects that are not,

like periodicals, instantly ephemeral; objects that you can get your hands

round, that rest on shelves, that last. Robert Arthur had three books

published, so I suppose he did slightly better than that other forgotten master

of the short story, Arthur Porges. Even so, it's always seemed to me that

Arthur was singularly unlucky, either with his agent or his publishers. Or

both.

His only

novel,

Somebody's

Walking Over My Grave (1

961), proves that his true metier was the short story and is notable

only for the most specious, not to say lunatic, editorial blurb I've ever come

across while his two volumes of shorts—

Ghosts And More Ghosts

(1963) and

Mystery And More Mystery

(1966)—were, insanely, packaged for

the juvenile market, sank without a trace pretty soon after they appeared, and

are now almost impossible to find. But well worth paying out large sums for if

you do stumble across copies. A hefty and representative collection of his

stories is (American editorial directors, please note) long, long, long

overdue.

Robert

Arthur could be extremely damn funny (some of the stories he sold to

Unknown

magazine are gems). He could also

be extremely not so damn funny. Here is a bleak little Christmas tale

guaranteed to bring a wry twist to the mouth. . .

Y

OUR name is

Purvis—Edward Purvis. You 're in your late thirties—a solid man, with a cold

solid face and small, unwinking eyes. Just now you're crouching in the darkness

beside a massive chimney on the broad, flat roof of an old building in the city

slums. From time to time you stamp your feet in the light snow. It's Christmas

Eve, and it's cold, and you've been waiting for an hour. But you know you won

't have to wait much longer.

The children on the floor below have begun to sing Christmas carols,

and the thin, high sweetness of their voices rises into the wintry night,

reaching you with sharp clarity except when the roar of a passing elevated

train, rushing by in the street well below the roof level, drowns them out.

Yes, it can't be long; the children are on their third carol now. . .

Silent Night, holy night,

All is calm, all is bright. . .

Purvis

shifted impatiently. He was warm and sweating inside the heavy sweater that he

wore beneath his suit coat. He wore no overcoat. He didn't have one, and if he

had, it wouldn't have been suitable to cat-footed creeping across roof tops. But

though the wind, when it came, was raw, and the night was crystal sharp with

the snap of a real Christmas Eve, he was sweating. Sweating with impatience,

maybe, because the blood was running so hot in this veins.

Round yon Virgin mother and Child. . .

Below him

was a gymnasium. Though he could not see through the snow-covered gravelled

roof under his feet, he knew it. Because this was the building of the St

Francis Foundling Home, and Ed Purvis had been a St Francis orphan.

Holy Infant, so tender and mild. . .

But that

had been a long time ago, before Purvis had become a member of a teen gang,

then a youthful mugger, then a dope peddler, and finally a killer.

Now it was

only important because it meant he knew the building thoroughly. Knew the

shabby gymnasium below where a hundred parentless children were singing,

joyously, as they waited for Santa Claus. Knew the fire escape that angled down

the side of the building next to the 'El' tracks, past the long frosted glass

windows.

And

especially because it meant he knew how to reach this roof from the roof of a

building three numbers away—exactly how to reach it unseen and unsuspected, so

that he could crouch in the shadows with a loaded gun in his pocket, and a

tape-wrapped length of pipe in his gloved hand, waiting, like the kids below,

for Santa Claus to come.

Sleep in heavenly peace,

Sleep in heavenly peace!

That needs explaining, doesn't it? Yes, of course it does. Because it's

a somewhat complex series of events that has brought you here to the roof to St

Francis Foundling Home on Christmas Eve, Ed.

So let us shift time and space about a bit. Let's turn the calendar

back to early December. And now the scene is the State Penitentiary, a hundred

miles to the north. It's Visitor's Day. And you, Ed, have a visitor. You 're a

convict, you 're not free and you don 't expect to be. But you have a visitor.

A girl. Her name is Red. Just Red. Your girl. It's foolish of her to love you

as desperately as she does. But that's how girls are. . .

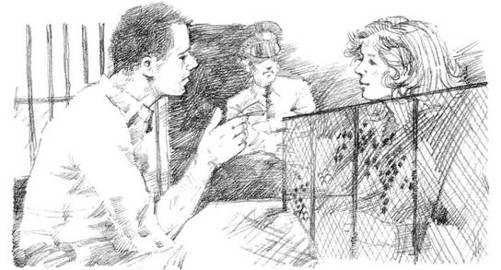

They sat at

one of those long tables with the little fence down the middle and stared at

each other hungrily. Purvis' square, brutal face was set and tight. Red's face

was white and pinched with too much rouge on her cheeks to cover the pallor and

too much lipstick on her lips. But her eyes were dark and sunken, needing no

eyeshadow, a look in them of fierce yearning.

'Ed,

honey,' she whispered. 'Ed, honest, I'm doing everything I can. You known Ed, I

want you out of here just as much as you want to be out. You know how I miss

you.'

Her eyes,

as she spoke, proclaimed her desperate sincerity. He was a killer, but she was

his girl, and she wanted him back.

'Money!'

Purvis rasped. 'That's all it takes to get a wise guy out of this joint. Four

or Five grand. Nothing else! If the boys—'

Red shook

her head, her lips tight. 'Ed,' she said huskily, 'the boys can't. McElroy got

them. He killed Willie Rand and wounded Nick and Gander Johnson. They're

waiting for sentence now. They'll get ten to twenty.'

Purvis's

face darkened. 'McElroy!' he whispered. 'Smiling Jim McElroy! That copper!

Someday I'll—'

'Ssh!' Red

warned sharply. 'The guard will hear you. What I wanted to tell you was this.

Lippy's left. Lippy and me. We managed to raise a thousand dollars. That's all.

'I took it

last night to you-know-who on the Parole Board. I told him it was all I could

raise. He wanted four grand. But I promised him more after you're out. He said

he'd do what he could.

'I don't

know if he means it or not, but it was the best I could do,' she added

desperately. 'Oh, Ed, I want you back so much—'

There were

tears in her eyes, winking bright as she leaned as close as the little fence

would let her. 'Ed, the Board meets tomorrow. You'll go up before them. You've

been here three years now. Surely they'll let you go! I got to have you back,

Ed. I'll die if you don't come back to me soon!'

Purvis

drummed softly with thick knuckles on the wooden table. His face was still dark

with the congested blood of anger.

'Okay,

Red,' he said, 'if that's the best you can do, that's the best. Even if it

works out, it'll mean I'm here another thirty days at least. But when I do get

out, there'll be one cop less who wants to see me fry. McElroy!

His voice

lowered, but in a whisper it was still savage. 'I'm going to kill him, see,

Red? I'm going to choke him with my own hands! I'll strangle him until his eyes

bulge, and his tongue sticks out of his mouth and he wants to beg for mercy but

can't! I'm going to kill that copper if it's the last thing I ever do!'

Red shook her

head frantically, so that the cheap permanent came loose and her hair straggled

down her face.

'No, Ed,

no,' she begged, brushing it back. 'Don't say that. Don't even think it!

They'll get you if you do it, Ed, and they'll send you to the chair. They'll

take you away from me, not for just a few years, but forever! Forever, Ed! And

that'd kill me. That'd—'

'Aaaaahhh!'

Purvish said, and it was like a long strangled curse deep in his throat. 'Not

me, they won't. If I could only get loose from here. Red, only get loose from

here before Christmas, I'd show them.'

From his

pocket he extracted a folded newspaper clipping, raggedly cut from a newspaper

with a thumb nail.

'Look at

this,' he said.

He raised a

hand, and the attendant guard ambled over. Suddenly Purvis' voice was mild.

'Can I show

this to the lady just for a minute?' he asked. 'It’s only a newspaper clipping

about a friend of ours.'

The Guard

scanned the clipping and grunted. 'Okay,' he said. 'Against the rules, but

there ain't anything harmful in it, I guess.'

He passed

the clipping to Red, and the girl spread it flat and read it. It was just a

headline and a few inches of text.

SANTA TO VISIT ORPHANS

Santa

Claus will visit without fail this year the St Francis Foundling Home, on

Melton Street. Not always has he stopped there on his annual visits, but from

now on his yuletide presence will be assured thanks to Sergeant James McElroy,

of the local police department, who took an interest in the institution when he

and his wife adopted a child from it recently.

Smiling Jim McElroy,

as he is called, is the most popular man in the department, and among the most

courageous, as was evidenced by his recent exploit of apprehending two fur loft

thieves and killing a third. So the response of the department when he took up

a collection to buy toys for kiddies who might otherwise go unremembered was

generous.

Thanks to Smiling

Jim, no kiddie in the St Francis Home will be neglected on Christmas Eve. Santa

will be there on schedule, and will even come in through a real fireplace, and

leave by the same route. Under Sergeant McElroy's expert direction, a large

imitation fireplace has been erected in the gymnasium, in front of a window

that leads to a fire escape.

Dressed as Saint

Nick, Sergeant McElroy, some time before midnight on Christmas Eve, will

descend the fire escape from the roof, emerge through the fireplace, and

delight the hearts of a hundred parentless tots with presents from the pack on

his back. Needless to say, the pack will be of ample dimensions.

There was

more to it, and a picture of a large man with a square chin, level gray eyes,

and a wide generous mouth that seemed made to grin good-naturedly. The girl

read it quickly. Then the guard handed the clipping back to Purvis and moved

away again to his post.

I don't

understand,' she said. 'What—'

'Don't be

dumb,' Purvis exclaimed impatiently. 'Don't you remember—I'm a St Francis

orphan myself. I didn't have any Santa Claus bringing

me

presents down a fake chimney, like

those dirty-nosed brats will. I got thrown out on my ear when I was twelve, and

thrown right in again—into the reformatory. But that isn't what I mean.

'What I

mean is, I known the St Francis home like I know the back of my hand. And if I

was on the outside, I'd be there waiting for McElroy when he came out on the

roof dressed as Santa Claus and started down the fire escape. I'd be waiting,

and I'd wipe the smile from his face and escape, and nobody would ever know who

did it. If you custom-tailored a bump-off, you couldn't arrange one that would

be any easier.

Catch on?'

Red nodded.

'Yes, Ed,' she said pleadingly. 'But please, Ed, please don't think about it. I

know McElroy sent you up, I know he broke up the gang. But think how lucky you

were he only got you for concealed weapons. If he'd ever found that witness he

was looking for, the one who saw you kill the watchman, you'd have gone to the

chair. Think how lucky you were, Ed, and forget about hating McElroy. Forget

him,

please!

'Tell me

what you'd like for Christmas instead. Tell me what you'd like, and I'll send

it to you. We'll just think about each other this Christmas and pretend we're

together like we will be when you get out.'

'He's still

looking for that witness,' Purvis said implacably. 'Some day he'll find him.

And so he has to die. If you want to know what I want for Christmas, I want

McElroy's life. That's what I want.'

'Oh, Ed,

Ed,' the girl cried, the tears wetting her thin cheeks, 'you'll get out and

kill him and they'll catch you and take you away from me forever—'

'Time!' the

guard said curtly. 'Time's up. You gotta go, lady.'

Red went,

still weeping, and Purvis put the clipping back in his pocket and opened and

shut his hands softly, thinking of what he'd do if only he were free to do it.

Well, now you 're free, Purvis. Free to hide on a snow-covered roof on

Christmas Eve, and stare at the crimson reflection of neon signs in the uptown

sky or at the glassless window of the tenement across the street where, from

time to time, a cigarette tip glows in one of the empty upper windows. Free to

crouch there waiting for Santa Claus, a St Nick who will be Jim McElroy dressed

up in crimson pants and false whiskers.

And when he comes you'll be able to give McElroy the present you've

brought him—the present of death. . .

It had been

completely unexpected when the guard had come for him only that morning and

said the warden wanted to see him. Purvis had stood scowling in the warden's

office, wanting to be insolent, but not quite daring to speak his mind, while

the little man behind the big desk stared at him with level, frosty eyes.

'Purvis,'

the warden said, tapping the desk with a pencil, 'You're surprised to be here.

And I'm just as surprised to see you before me.'

He smiled

bleakly. Purvis waited, wondering.

'We're both

surprised. And frankly, for me the surprise is unpleasant. But the Parole Board

has granted your request, and ordered me to turn you loose. You may regard it,

if you wish, as a Christmas present from the state.'