Cyclopedia (36 page)

Authors: William Fotheringham

There have also been specifically political cycling movements. In the early 20th century the German Workers Cycling Federation boasted 150,000 members while socialists across Great Britain formed an entire network of Clarion cycle clubs in the 1890s. At one time the Clarion clubs numbered over 100, running houses where the members could socialize in between holding rallies and distributing Socialist literature from their bikes. There are still 24 Clarion cycle clubs in Britain, but they are not politically affiliated.

Politicians still like to be seen with successful cyclists. Various French presidents, including Nicolas Sarkozy, have visited the Tour de France. Greg LeMond and Lance Armstrong were both invited to the White House after their respective Tour de France victories. George Bush senior was photographed with his wife Barbara on bikes in China in the 1970s. After the British Olympic cycling team's success in Beijing in 2008, Prime Minister Gordon Brown invited the team head, Dave Brailsford, to speak at the Labour party conference. But jumping onto the bike bandwagon doesn't always work out. Brailsford made a point of telling Labour about the virtues of a team sticking together, at a time when the government was riven by infighting.

On the other side of the spectrum, the current British prime minister David Cameron will always remain the politician who rode his bike to workâwith a car following behind him carrying his bag and his shoes. George W. Bush fell off his bike, funnily enough, but perhaps the ultimate letdown came when former French president Jacques Chirac invited the Tour de France to his fiefdom in the Dordogne in 1998 only for one of the biggest drugs scandals in the race's history to ruin the party.

POLO

Bicycle polo was a demonstration sport at the London OLYMPIC GAMES in 1908. The gold went to IRELAND, which was the nation where the sport was founded in 1891 by one Richard J. Mecredy.

Bicycle polo was a demonstration sport at the London OLYMPIC GAMES in 1908. The gold went to IRELAND, which was the nation where the sport was founded in 1891 by one Richard J. Mecredy.

Bicycle polo is exactly what it sounds likeâa version of the horseback game on two wheels, with steeds that don't eat and can be bought by the common man. Field dimensions vary from 150 by 100 meters to 100 by 80 meters (for some reason the French prefer a smaller field). The ball is 12 to 15 inches around, the mallets three feet long. Six or seven players make up a team, with four or five on the field at once. (Similarly, the French like a different number of players.) Internationals last 30 minutes broken up into four seven-and-a-half minute chukkas. If a match runs to extra time, the goals may be widened. The rules are simple: a sliding scale of extra hits or goals for fouls, yellow and red cards. The UCI recognizes cycle polo and there is an annual world championship. India, USA, and Canada are among the strongest nations.

POSTERS

The rapid expansion in bicycle production at the end of the 19th century (see BICYCLE for background) produced intense competition between bike makers who vied to produce the most attractive posters to sell their products. In Paris, where decorative poster art had begun in the mid-19th century with the lithographic printing work of Jules Chéret, there was a brief period when art and cycling came together. Artists such as

HENRI DE TOULOUSE-LAUTREC and Palâthe nom de plume of Jean de Paleologueâglamorized cycling with the same talent that had been used to advertise the exoticism of Paris's demi-monde with its revues such as those at the Moulin Rouge.

The rapid expansion in bicycle production at the end of the 19th century (see BICYCLE for background) produced intense competition between bike makers who vied to produce the most attractive posters to sell their products. In Paris, where decorative poster art had begun in the mid-19th century with the lithographic printing work of Jules Chéret, there was a brief period when art and cycling came together. Artists such as

HENRI DE TOULOUSE-LAUTREC and Palâthe nom de plume of Jean de Paleologueâglamorized cycling with the same talent that had been used to advertise the exoticism of Paris's demi-monde with its revues such as those at the Moulin Rouge.

Many of the images were risqué for the time: a naked woman with the wings of Mercury publicized Gladiator cycles; a bare-breasted Amazon (by Pal) the appropriately named Liberator Cycles; cycling lessons at the Palais-Sport in Paris were advertised by a young lady in suspenders. The British firm Humber used a more staid gentleman in regulation Cyclists' Touring Club gear but also a coquettish ad with a young gentleman stealing a kiss from his riding partner.

Most distinctive of all, however, was Toulouse-Lautrec's depiction of an early race at London's Catford Velodrome to publicize the Simpson chain sold by Spoke's bike shop.

La Chaîne Simpson

includes the early champion Constant Huret amid a variety of multiple pacing bikes and raffish onlookers. (See ART to read about other greats who have used cycling for inspiration.)

La Chaîne Simpson

includes the early champion Constant Huret amid a variety of multiple pacing bikes and raffish onlookers. (See ART to read about other greats who have used cycling for inspiration.)

To give some idea of what these posters are worth, an original of Pal's native American chief advertising Cleveland cycles can be bought for under $10,000 while an original of

La Chaîne Simpson

has been valued at nudging $100,000.

La Chaîne Simpson

has been valued at nudging $100,000.

Aficionados could also seek out posters used to advertise the Peace Race (see EASTERN EUROPE), in the distinctive heroic style of Socialist Realist art.

POULIDOR, Raymond

(b. France, 1936)

(b. France, 1936)

The most popular cyclist FRANCE has ever produced was still a fixture at the Tour more than 40 years after his heyday in the 1960s when he went head-to-head with JACQUES ANQUETIL in one of the greatest RIVALRIES cycling has seen. “Poupou” never won the Tour and never wore the yellow jersey, but he did win hearts for his shy smile, constant misfortune, and the courage he showed in attacking first Anquetilâhis equal in the mountains and far superior in the time trialsâand later EDDY MERCKX, who was simply better in every domain.

At the peak of his celebrity it was estimated that he would be first choice as a dinner guest for almost half the French population. It was said that while French men admired Anquetil for his success, their wives all wanted to mother his great rival. His nickname gave rise to the headline

Poupoularité

, while politicians refer to Poulidor syndrome: France's perceived tendency to accept being a worthy loser rather than a clinical winner. His memoirs summed up his career:

La Gloire sans le Maillot Jaune

(1977).

Poupoularité

, while politicians refer to Poulidor syndrome: France's perceived tendency to accept being a worthy loser rather than a clinical winner. His memoirs summed up his career:

La Gloire sans le Maillot Jaune

(1977).

Born of farming stock in the Massif Central, Poulidor seemed the country boy alongside the more sophisticated Anquetil and he raced in an agricultural way, more reliant on brute strength than tactics. He still won the VUELTA A ESPAÃA and MilanâSan Remo but is better remembered for his incredible record in the Tour: 14 starts and 12 finishes, with 11 top 10 overall placings and 8 finishes in second or third overall. The moment when he captivated France came in the 1964 race when he and Anquetil fought out an elbow-to-elbow battle on the Puy-de-Dôme, with Poulidor gaining the upper hand on that occasion but narrowly missing out on the yellow jersey. His career was a model of LONGEVITY, with third-place Tour finishes in 1962 and in 1976 when he was 40 years

old. Since retirement that year, Poulidor has returned to the race every year, and is the undisputed star of the publicity caravan promoting products as diverse as banks and coffee.

old. Since retirement that year, Poulidor has returned to the race every year, and is the undisputed star of the publicity caravan promoting products as diverse as banks and coffee.

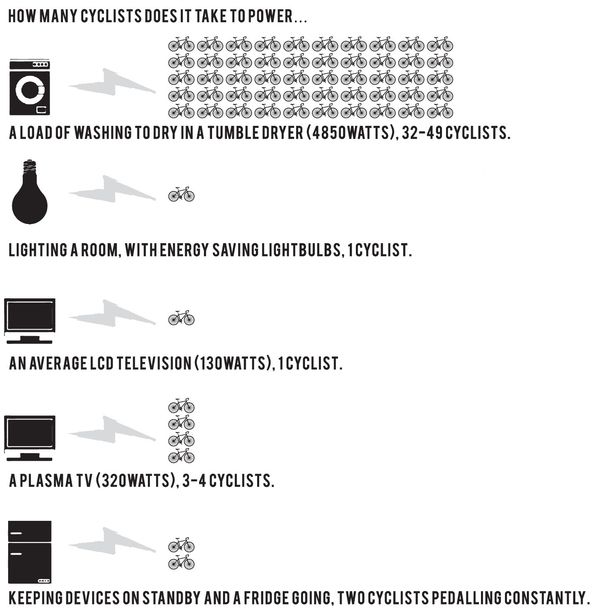

POWER

The question of how many lightbulbs a cyclist can power has been kicked around for over a century and gained new resonance in the 1990s as it became possible to make an accurate measurement of the wattage produced by a bike rider using POWER CRANKS. Generating stations powered by bikes were used in England in the early 20th century, while BSA produced a cycle generator for the army to power lights and communication devices in the field during the Second World War.

The question of how many lightbulbs a cyclist can power has been kicked around for over a century and gained new resonance in the 1990s as it became possible to make an accurate measurement of the wattage produced by a bike rider using POWER CRANKS. Generating stations powered by bikes were used in England in the early 20th century, while BSA produced a cycle generator for the army to power lights and communication devices in the field during the Second World War.

In a sprint, a top cyclist can put out about 2,500 watts for about 5 seconds; over a more sustained effort, say 10 seconds, it would be about 1,800 watts; in a 4-minute track pursuit, about 500 watts; in a time trial, a cyclist with BRADLEY WIGGINS's physique, for example, could sustain about 430 watts for an hour; on an easy training ride where it's possible to talk to your neighbor, the average cyclist would be putting out around 200 watts.

An investigation by the BBC's

Focus

magazine in October 2009 concluded that if the average “reasonably fit” cyclist's sustained power output was between 100 and 150 watts of energy, a family home would need about 100 cyclists on permanent standby to keep all its electrical devices functioning. The Human Power Station came up with the following: A load of washing to dry in a tumble dryer would require 32 to 49 cyclists pedaling for an hour (4,850 watts). Lighting a room with energy-saving lightbulbs could be dealt with by just one bike rider. An average LCD television (130 watts) would need one cyclist; a plasma TV (320 watts), three or four cyclists. And merely keeping devices on standby and a fridge going would need two cyclists pedaling constantly. And making your morning coffee (800 watts), that would call for 8 to 10 cyclists, depending on how many cups you need.

Focus

magazine in October 2009 concluded that if the average “reasonably fit” cyclist's sustained power output was between 100 and 150 watts of energy, a family home would need about 100 cyclists on permanent standby to keep all its electrical devices functioning. The Human Power Station came up with the following: A load of washing to dry in a tumble dryer would require 32 to 49 cyclists pedaling for an hour (4,850 watts). Lighting a room with energy-saving lightbulbs could be dealt with by just one bike rider. An average LCD television (130 watts) would need one cyclist; a plasma TV (320 watts), three or four cyclists. And merely keeping devices on standby and a fridge going would need two cyclists pedaling constantly. And making your morning coffee (800 watts), that would call for 8 to 10 cyclists, depending on how many cups you need.

POWER FACTOID

A sprint cyclist making a starting effort produces, briefly, more torque than a Formula One car. Team GB's team sprint Man One Jamie Staff can put out 600 newton meters in the first half of his first pedal revolution.

4

POWER CRANKS

There are several ways of measuring POWER outputâsensors in the chain, sensors on the roller of a stationary home trainerâbut the SRM (Schoberer Rad Messtechnik) German-made crankset is the best. It has eight strain gauges that measure the deflection in the chain ring as a cyclist pushes down on the pedals. The information is translated into a measure of the power output in watts, which can in turn be downloaded into a computer.

There are several ways of measuring POWER outputâsensors in the chain, sensors on the roller of a stationary home trainerâbut the SRM (Schoberer Rad Messtechnik) German-made crankset is the best. It has eight strain gauges that measure the deflection in the chain ring as a cyclist pushes down on the pedals. The information is translated into a measure of the power output in watts, which can in turn be downloaded into a computer.

The cranks first appeared in the mid-1990s and had a large, crude handlebar computer; this has now been shrunk to the extent that pro cyclists carry the devices in races. The cranks are integral to most serious training programs as they offer the best objective measure of how hard a cyclist is able to work. Heart-rate monitors appeared at the end of the 1980s, and are accurate, but pulse rate is subject to factors such as heat and fatigue, which

make training to a set rate difficult: on the other hand, you can either reach a set power output or you can't.

make training to a set rate difficult: on the other hand, you can either reach a set power output or you can't.

Information from the cranks is one of the keys to the success of the GREAT BRITAIN cycling team (see CHRIS HOY, BRADLEY WIGGINS). “We can understand the physics of what is going on, so we can tell where best to spend our time and energy,” the team's then performance scientist Scott Gardner explained in 2008.

The team has over 100 of the cranksâcosting about £2,000 eachâand employs a technologist in the Manchester Velodrome whose principal task is to ensure they are always perfectly calibrated.

They use the data to tweak training programs and to devise strategies for track racesâfor example, the graphs showing the riders' power output for a team pursuit can be compared with their speed to see how the formation can be changed to be most efficient. SRM information can also be used to model performance on a treadmill: the precise power outputs on an SRM file for a mountain-bike race, say a rehearsal on the Beijing course, could be replicated in training.

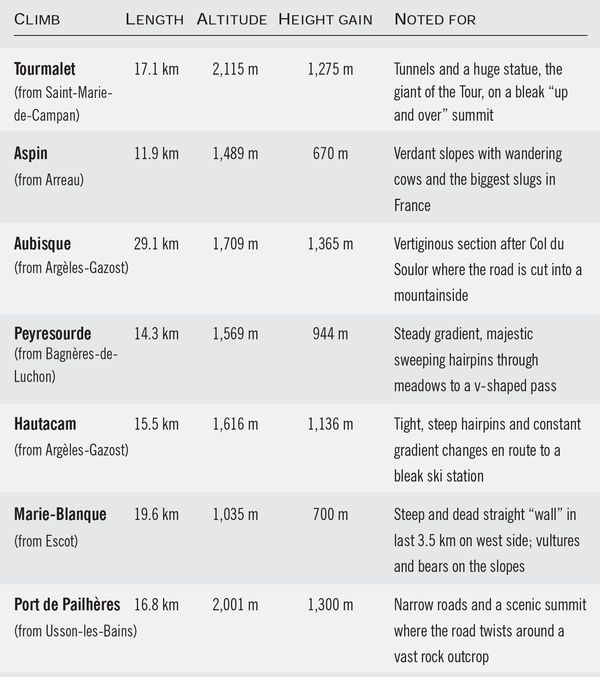

PYRENÃES

The inclusion of France's southern mountain range in the TOUR DE FRANCE route in 1910 was a turning point for cycling. The race organizer HENRI DESGRANGE sent the riders over four climbs that have acquired legendary status: the Peyresourde, Aspin, Tourmalet, and Aubisque. It was on the latter that the key episode occurred: the eventual race winner Octave Lapize (see HEROIC ERA) went past a group of organizers and spat out the word “assassins.” Desgrange was absent: uncertain whether the first mountain stage would be a success he decided to stay away. Nonetheless, he was instantly

aware of the headlines that could be made by sending Tour cyclists where mere mortals dared not venture, so next year he sent the Tour into the ALPS.

The inclusion of France's southern mountain range in the TOUR DE FRANCE route in 1910 was a turning point for cycling. The race organizer HENRI DESGRANGE sent the riders over four climbs that have acquired legendary status: the Peyresourde, Aspin, Tourmalet, and Aubisque. It was on the latter that the key episode occurred: the eventual race winner Octave Lapize (see HEROIC ERA) went past a group of organizers and spat out the word “assassins.” Desgrange was absent: uncertain whether the first mountain stage would be a success he decided to stay away. Nonetheless, he was instantly

aware of the headlines that could be made by sending Tour cyclists where mere mortals dared not venture, so next year he sent the Tour into the ALPS.

The climbs of the Pyrenées have a different character compared to those in the other major Massif. They tend to be shorter than in the Alps and do not climb so high. The only pass over 2,000 m in the Pyrenées that is regularly climbed in the Tour is the Tourmalet, a mere 2,115 m compared to over 2,600 m for the Galibier and Iseran in the Alps.

On the other hand, the Pyrenées offer steeper climbing, and roads that have been less well engineered: evenly graded hairpins and wide carriageways are relatively rare. “Walls” such as the Col de Marie-Blanque and the Col de Bagarguiâaround 13 percentâare typical, as are narrow, tightly hairpinned climbs such as the Col d'Agnès.

The slopes of the mountains around the climbs tend to be gentler and greener, less spoilt by ski resorts and industry.

As in the Alps, numerous CYCLOSPORTIVE events take in the great climbs. They include the Hubert Arbes, run by one of BERNARD HINAULT's old teammates, which takes in the Tourmalet and the Soulor/ Aubisque; from the Spanish side, the Quebrantahuesos sportif includes the Marie-Blanque.

Â

Further reading:

Tour Climbs

, Chris Sidwells, Collins, 2008

Tour Climbs

, Chris Sidwells, Collins, 2008

Â

(SEE

RAID PYRENEAN

FOR AN INFORMAL IF PAINFUL WAY TO TACKLE THE GREAT CLIMBS IN ONE GO)

RAID PYRENEAN

FOR AN INFORMAL IF PAINFUL WAY TO TACKLE THE GREAT CLIMBS IN ONE GO)

Other books

Tamar by Mal Peet

Seas of Venus by David Drake

The Shivering Sands by Victoria Holt

Cam - 04 - Nightwalkers by P. T. Deutermann

All Strung Out by Josey Alden

My Father's Fortune by Michael Frayn

Betrayed by Alexia Stark

Be Not Afraid by Cecilia Galante

Miss Buddha by Ulf Wolf

Thunder Road by James Axler